Feeling cold is increasingly a privilege in our warming world. Regions of the world known for temperate, moderate climates are becoming accustomed to erratic weather. Cooler areas of the globe are warming, and warmer areas becoming too hot to occupy. Accompanying these climatological transformations are humanity’s attempts to control temperature, led by the invention of technologies (most prominently air conditioning) which help us live comfortably, but which come with substantial human, economic, and environmental costs. By creating pleasant temperatures in which to live and work, we exacerbate the problem that makes human intervention into the climate more urgent.

The cause of these changes is the consumption of fossil fuels, which transformed human life profoundly in the pursuit of modernity. The origin of this transformation falls squarely within the long eighteenth century. The established scientific terminus post quem for measuring human effects on global temperatures is the year 1800. Moreover, the 1700s were the final century of the Little Ice Age, a climatological phenomenon characterized by lower global mean temperatures. With these conditions in mind, might temperature play a greater role in our discussion of eighteenth-century art? For this issue of Journal18, I have invited scholars to address this possibility. My goal is to encourage reflection on how eighteenth-century art might engage the scholarly literatures on historical climatology and the history of the senses. Do the conditions of eighteenth-century life, as filtered through artistic production, help us understand why the world became warmer? Can we find in the eighteenth century’s ideas about temperature the roots of our current beliefs, and perhaps locate in art ways of rethinking or undoing the assumptions that have brought us to this place?

The essays offered here address these concerns from multiple perspectives, engage varied works of art, and do so in diverse regions of the globe. Jennifer Van Horn examines an eighteenth-century plate warmer, made circa 1790, owned by George Washington and used in his residences, to reveal its place within a racially determined temperature-scape. She achieves this by analyzing not only how it mediated temperatures for its socially prominent owners, but also how it reveals the experiences of the enslaved individuals who tended it during dinners. She thereby locates the warmer’s effect on bodies, its thermoception, within the “complex entanglements of cold, race, unfreedom, and materiality” of early America to produce a “racialized thermal order.”

Sylvia Houghteling’s essay takes us to a different region of the globe, South Asia, and to a different problem, namely creating cool temperatures for inhabitants of a hot climate. Houghteling shows that South Asian societies produced sophisticated systems of cooling long before colonial occupation, but these early techniques often relied on creating the psychological effect of cold by stimulating other senses, notably smell and sight. She thereby produces a synesthetic framework for temperature modification, one in which the senses interconnect. This approach offers insight into how to produce art history that is sensually engaged, not just in an erotic dimension, but in the ability to imagine complex sensual entanglements through the past’s material remains.

Alper Metin leads us to the Ottoman Empire, where he investigates the history of a warming device appreciated across the world: the fireplace. Eighteenth-century Ottoman patrons adapted fireplace designs from Western models, and in so doing responded to substantial socioeconomic and cultural changes in Ottoman society. These included the desire for increased comfort in domestic interiors and the need to display wealth and sophistication through a fireplace’s decoration. Metin reflects on the Ottoman Turkish terminology for fireplaces, revealing both gendered and socio-ethnic dimensions to its language, and on morphological changes to fireplace design. Fireplaces emerge as more than just warming devices, but rather as creations that express changing conditions and mentalities in a society rethinking its international place.

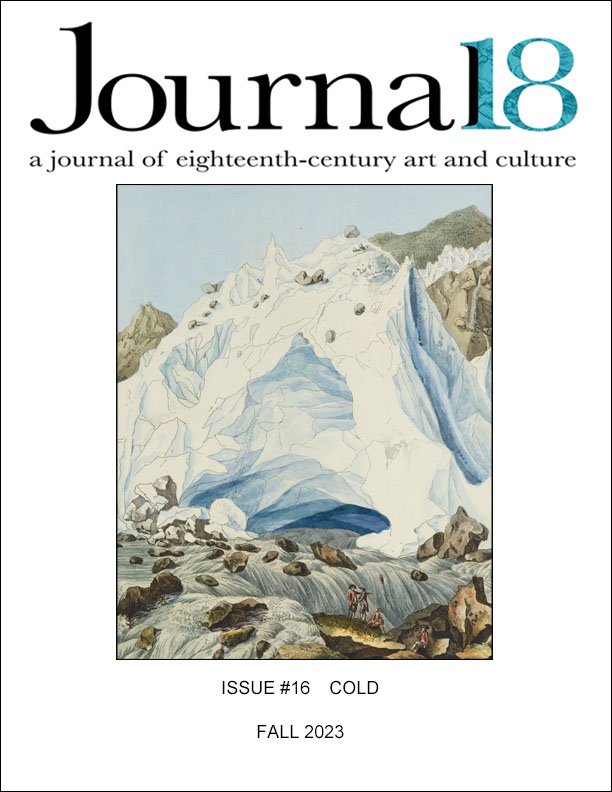

Our shorter notices take up these themes in further directions. Kaitlin Grimes shows how the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway incorporated narwhal ivory into conceptions of royal power that both supported and materialized its colonial project in the Arctic Atlantic. Etienne Wismer demonstrates that melting glaciers in Switzerland (much in the news today) fascinated Europeans in the years around 1800, spurring scientific investigations, inspiring interior decoration, and generating new health regimens. Both Grimes and Wismer explore the relationship between what Wismer calls a “biotope” and the human beings who inhabited it. I would add that art mediates the relationship between humanity and biotope, and that temperature is a central force constituting their interconnection.

Issue Editor

Michael Yonan, University of California, Davis

ARTICLES

Racialized Thermoception: An Eighteenth-Century Plate Warmer

Jennifer Van Horn

Beyond Ice: Cooling through Cloth, Scent, and Hue in Eighteenth-Century South Asia

Sylvia Houghteling

Domesticating and Displaying Fire: The Technical and Aesthetic Evolution of Ottoman Fireplaces

Alper Metin

SHORTER PIECES

Narwhal Ivory as the Arctic Colonial Speciality of the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway

Kaitlin Grimes

Making Sense of Ice? Engaging Meltwater in the Long Eighteenth Century in Switzerland and France

Etienne Wismer

Cover image: Carl Ludwig Hackert, View of the Arveron Source, c. 1781. Etching and watercolor on paper, 34.5 x 46.5 cm. Swiss National Library, Prints and Drawings Department, GS-GUGE-HACKERT-B-8. © Swiss National Library, Prints and Drawings Department.