The recent death of Vivienne Westwood (1941–2022), Britain’s most influential fashion designer of the last fifty years, gives us cause to reflect on the eighteenth-century art and fashion that inspired her designs. Taking a closer look at her collections from the 1990s reveals a deep and abiding love for eighteenth-century French art in the Wallace Collection— a place that would become the source, and occasionally the stage, for some of her most celebrated creations.

Westwood and her then partner, Malcolm McLaren, first rose to fame in 1976 as the innovators of the punk street wear that they sold from their shop, Sex, at 430 Kings Road in London.[1] After Sid Vicious, the bassist for the punk group the Sex Pistols, died in 1979, Westwood and McLaren were looking for a new direction. It was then that the designer turned to early-modern clothes for inspiration. McLaren became interested in New Wave pop music, particularly the concept of do-it-yourself sampling and pirating made possible with audio cassettes. His new group, Bow Wow Wow, produced the first single sold on cassette: C30, C60, C90, Go! The title of the song was a reference to lengths of blank cassettes with which you could record (pirate) songs from the radio.[2] McLaren wanted a new look for the band, so Westwood started to research how pirates of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries dressed (Fig. 1).[3]

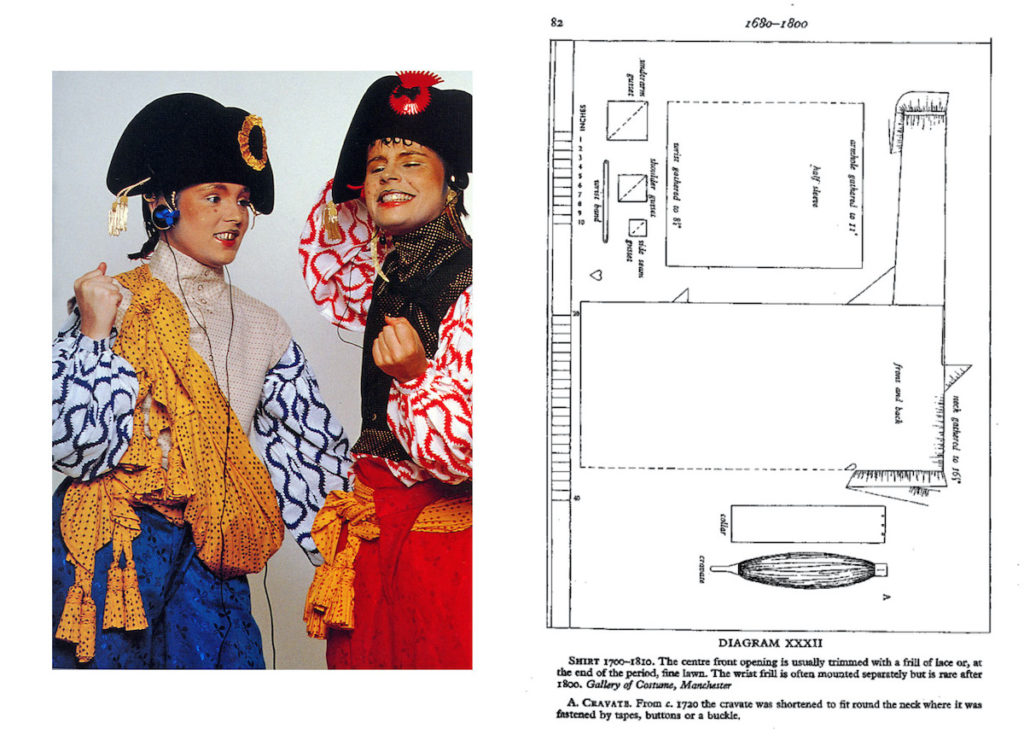

RIGHT: Fig. 2. Illustration from Norah Waugh, The Cut of Men’s Clothes, 2nd edition (Boston: Faber and Faber, 1977), 82.

Ben Westwood, Vivienne’s son, attributes McLaren and Westwood’s initial interest in that look to a book that McLaren brought home in around 1979: Douglas Bottling, The Pirates.[4] It was in Bottling’s book that McLaren found seventeenth-century British pirate Thomas Tew’s flag bearing the arm and sword design that remains the logo of Westwood’s Worlds End boutique in Chelsea.[5]

Perhaps it was that same source, or one of the books that Westwood studied at the Victoria and Albert Museum Art Library where she found a historical engraving of a pirate, that inspired one of her most enduring and recognizable asymmetrical designs:

When I did the Pirate collection I’d seen an engraving of a pirate whose trousers were too big and they were all kind of rumpled about the crutch [sic]… I wanted to do that, but I couldn’t pull that trouser off until I found a book that showed how people made breeches in those days, and I found that the shape of trousers was quite, quite, different. Once I realized that, I got my look. I wanted a rakish look of clothes which didn’t fit.[6]

The sculptural quality of Westwood’s clothes from those early days, with the play of draped and tightly wrapped fabrics, was informed by historical study. She examined the construction of early-modern garments reproduced in Norah Waugh’s book, The Cut of Men’s Clothes (1977), with the pattern for an undershirt made from squares and oblongs of fabric, with triangle gussets under the arm, connecting it to the body (Fig. 2).[7] By adjusting the placement of the neck hole—not at the top of the shoulder seam, but lower in the front—the fabric draped pleasingly against the body, giving the appearance of lively, billowing drapery evocative of that observed in paintings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Pirate Boots made for the collection, which remain a signature design for the fashion house, can be worn with the top folded down, emulating the form of seventeenth-century riding boots. Combined with the cocked hat, trimmed with a cockade—a nod to military attire often worn by pirates and the Incroyables of post-revolutionary Paris—the Pirate collection was historical but also outside of time. Through historical quotation, Westwood created a timeless, avant-garde style immune to the vicissitudes of the fast-paced fashion industry.

Westwood’s fascination for the eighteenth century was encouraged by her “intellectual personal trainer,” Nelson “Gary” Ness (1928–c. 2005), an artist, aesthete, and intellectual who guided Westwood’s study of the past.[8] Westwood described her friend as “the biggest influence on my life bar none.”[9] Ness was born in Canada, but moved to Paris to study art at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in the 1950s. He was a Francophile through and through, who “saw in the political emancipation of the Age of Revolutions the seeds of decay in Western culture.”[10] Ness encouraged the designer to draw inspiration from history, as Westwood recalled:

Gary helped me most in this […] in the idea that great art is as alive today as when it was first done. That the past is relevant. It gave me the confidence to say that true culture is not about a break with the past. And people in fashion can get very irritated by this, and by my quoting and making historical reference, but I hated it when I was called anachronistic, because I knew that time was on my side; if art is original it fits into tradition.[11]

It may have been Ness who introduced Westwood to the Wallace Collection in London, which the designer frequently called her favorite museum, and a place that inspired her pirate-like tendency for appropriation.

Dame Rosalind Savill, Director of the Wallace Collection from 1992 to 2011, recalls one of her early encounters with Westwood when the latter posed, with her husband/collaborator, Andreas Kronthaler, in the collection for a risqué photoshoot.[12] The photograph in question shows Westwood in a silk gown from her Café Society collection (Spring/Summer 1994), with Kronthaler naked beside her, his hair fashioned into satyr’s horns. Savill was concerned that the museum’s trustees might not be keen on the image. That was one of several occasions when the designer “innocently pushed the boundaries of what a national museum might have expected, but the Wallace was small and proactive enough to have turned this to a very special relationship with her.[13]”

While Westwood had been playing with historical forms since her first collection, her signature style that incorporates the bustle and corset of eighteenth-century dress was first introduced in the mid-1980s. The bustle in the Mini-Crini collection (Spring/Summer 1986) was developed as an antidote to the broad shoulder and narrow hip silhouette of the 1980s, moving towards historical ways of shaping and exaggerating the hips. Westwood’s famous corset was introduced for the first time in the Harris Tweed collection (Autumn/Winter 1987–88), a form that has become a staple for the house and continues to feature in collections to this day. Where the Harris Tweed collection drew inspiration from British fashion, reimaging the frumpy country-house aesthetic of the landed gentry, the collections in the years that followed turned increasingly towards eighteenth-century France.

While the Voyage to Cythera collection (Autumn/Winter 1989–90) took its title from Jean-Antoine Watteau’s famous 1717 painting, the first direct quotations of eighteenth-century French decorative art came the following year in Pagan V (Spring/Summer 1990).[14] That collection included patterns taken directly from Sèvres porcelain in the Wallace Collection. The nets, fluting, and scalloped patterns on porcelain vases and tea services were abstracted to form navy, teal, and gold shapes on light, billowing fabrics. Among the objects that inspired these Sèvres patterns is a cup and saucer set that had languished in the basement of the Wallace, long thought to be a later nineteenth-century example, before Savill recognized it as an eighteenth-century piece.[15]

But it was the next collection, Portrait (Autumn/Winter 1990–91), that would take direct quotations of objects in the Wallace Collection further. Two objects reproduced by Westwood were to become very closely associated with her oeuvre: a Boulle mirror from 1713 with an exquisite marquetry back (Fig. 3), and François Boucher’s Daphnis and Chloe (1743).[16] Westwood frequently acknowledged her debt to the Wallace, stating in a short film she recorded for the museum in 2009 (Fig. 4):

My collection that was most inspired by the Wallace Collection was a collection called Portrait. I wanted to use the things that most epitomized paintings. And for example, I chose pearl drop earrings because I decided that was the most typical jewelry throughout the century somehow. I designed a special hat that would look just as good as someone in 1930, 1830, 1730, a sort of little trilby type thing. I wanted canvas in my collection and even more I wanted an actual photographic painting and that is when I decided to choose the Boucher, as being so typical and so pretty. I had it printed on corsets.[17]

Fig. 4. Vivienne Westwood, “Vivienne Westwood on the Wallace Collection,” YouTube video. 5:17, October 1, 2009, https://youtu.be/v_-XK5WaZEo.

Westwood had not sought clearance from the Wallace Collection to reproduce those objects on her clothing. Savill recalls seeing a picture of Jeff Koons with his wife La Cicciolina wearing a Westwood Boulle dress, prompting her to write to the designer to inform her of the breach of copyright.[18] Westwood responded that “she had photographed it from the back of the Wallace guidebook and surely that was fine.”[19] As Savill recalls: “Although Vivienne may have broken our rules, I loved her for it and it enabled us to be so much more engaged and creative with her.”[20] So the museum staff did not pursue the claim. Instead, they persuaded the fashion house to allow them to display two signature corsets for sale in the Wallace Collection shop.[21] Savill only remembers one of the corsets selling to an international tourist.[22] Westwood has continued to reproduce Boucher’s Daphnis and Chloe on t-shirts, shirts, jackets, jeans, and shoes. Indeed, the Boucher print has become one of the most recognizable images associated with the brand, and new designs featuring the print frequently sell out.

For her first stand-alone menswear collection Cut and Slash/Pitti Uomo (Spring/Summer 1991), held in the seventeenth-century Villa Gamberaia near Florence, Tuscany, Westwood was inspired by historical clothes from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. Much of the collection featured slashed, torn, and perforated clothes, mimicking sixteenth- and seventeenth-century doublets that exposed layer upon layer of costly materials with decorative holes. The collection also included three-piece suits emulating men’s grand habit—justaucorps, vest, and culottes—bordered with flowers recalling the fashion of Louis XV’s court. The model wore a perruque and lace cravat, making the historical reference explicit.

Fig. 5. Vivienne Westwood t-shirt with an image of the Large Drawing Room in the Wallace Collection. Collection unknown, c. 2011. © Photo by the author.

References to eighteenth-century decorative arts, paintings, and clothes were most pronounced in Westwood’s collections of the early to mid 1990s. The Salon collection (Spring/Summer 1992) embodied a desire shared by Ness and Westwood for a return to the cultured civility of the eighteenth-century salon tradition: a place of art, fashion, and the sharing of ideas. The signature print for the collection was a photograph of an interior in the eighteenth-century style taken from World of Interiors magazine. Westwood would later reproduce the Large Drawing Room of the Wallace Collection (after the sumptuous renovation led by Savill), with its green damask silks, filled with exquisite eighteenth-century French decorative arts, for a series of t-shirts, sweaters, tracksuits, jackets, and trousers (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6. François Boucher, Madame de Pompadour, 1759. Oil on canvas, 91 x 68 cm. Wallace Collection, London. © Wallace, CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Westwood’s most ebullient homage to eighteenth-century French dress is to be found in the voluminous gowns shown in her Café Society (Spring/Summer 1994), Vive La Cocotte (Autumn/Winter 1995-96), and Les Femmes Ne Connaissent Pas Toute Leur Coquetterie (Spring/Summer 1996) collections. One gown from Vive La Cocotte (cocotte being slang for a courtesan) is inspired by a Boucher portrait of the most celebrated courtesan of the eighteenth century, Madame de Pompadour, at the Wallace (Fig. 6).[23] The details of Westwood’s homage closely match the painting: the graduated bows on the stomacher, the open sleeves of the jacket with billowing lace below, and the trimmings on the skirts match the robe à la française of the portrait. But the pastel shades of Pompadour’s dress in the painting are exaggerated in candy pinks and blues by Westwood, accentuating the courtly artifice of the gown and bringing it sharply into the present. The homage to the original painting found its moment of perfection when Vivienne wore the Pompadour dress herself to launch the 2002 exhibition The Art of Love: Madame de Pompadour and The Wallace Collection.[24]

The death of Gary Ness in 2005 marked a new chapter in Vivienne Westwood’s life and work, as she turned her focus to activism. Propaganda (Autumn/Winter 2005-06) was her first overtly political collection. Drawing upon her visual lexicon, Westwood reintroduced text into her collections for the first time since her punk t-shirt of the 1970s. The word “propaganda” on head bands, t-shirts, and printed fabrics was combined with Westwood’s historically informed draping and tailoring. The spirit of the eighteenth century in billowing fabrics and tight waists was combined with a revolutionary cry for the world to wake up to the insidiousness of late-stage capitalism. When she launched her Active Resistance to Propaganda manifesto in 2007, Westwood chose to do so at the Wallace Collection, surrounded by the eighteenth-century art and design that inspired her most memorable work.[25] The designer understood how the humor, sexuality, and sensuousness of Boucher’s paintings belonged to age of the salonnière, the intellectual woman, like Pompadour, who combined sensuality and intellect to command power. Westwood’s eighteenth century was one of an Enlightenment sensibility to question the status quo.

Robert Wellington is Associate Professor and Director of the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Dame Rosalind Savill for speaking to me about her experience of Vivienne Westwood’s relationship with the Wallace Collection, and for the feedback she provided on this article.

[1] For Vivienne Westwood’s complete collections, see Alexander Fury, Vivienne Westwood, and Andreas Kronthaler, Vivienne Westwood Catwalk (London: Thames and Hudson, 2021).

[2] Claire Wilcox, Vivienne Westwood (London: V&A Publications, 2004), 16.

[3] Vivienne Westwood and Ian Kelly, Vivienne Westwood (London: Picador, 2014), 236-37.

[4] Ben Westwood, “The Pirate Thomas Tew & the Worlds End Logo,” Vivienne Westwood (blog), 2017/11/08): https://blog.viviennewestwood.com/the-pirate-thomas-tew-the-worlds-end-logo/; Douglas Botting, The Pirates (Netherlands: Time-Life Books, 1978); Benjamin Capps, The Great Chiefs Pirates (Netherlands: Time-Life Books, 1975).

[5] Westwood, “The Pirate Thomas Tew.” I thank to Darren Eskriett for bringing this to my attention.

[6] Vivienne Westwood cited in Wilcox, Vivienne Westwood, 15-16.

[7] Norah Waugh, The Cut of Men’s Clothes,2nd ed. (Boston: Faber and Faber, 1977).

[8] Stephen Todd, “No Brain, No Gain,” New York Times Magazine,September 22, 2002, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/09/22/magazine/no-brain-no-gain.html. Gary Ness’s self-portrait was published on Vivienne Westwood’s Climate Revolution website: https://climaterevolution.co.uk/wp/2013/07/30/viviennes-diary-1-26-july/, accessed March 27, 2023.

[9] Westwood and Kelly, Vivienne Westwood, 298.

[10] Westwood and Kelly, Vivienne Westwood, 303.

[11] Westwood in Westwood and Kelly, Vivienne Westwood, 302.

[12] Dame Rosalind Savill, in discussion with the author, February 16, 2023.

[13] Dame Rosalind Savill, correspondence with the author, March 30, 2023.

[14] It was Gary Ness who devised the titles for Westwood’s collections. Westwood and Kelly, Vivienne Westwood, 302.

[15] Savill, in discussion with the author.

[16] On Westwood’s use of Boucher’s Daphnis and Chloe,see Melissa Hyde and Mark Ledbury, “Rococo to the Max: Pompadour’s Profusion,” The Era of Madame de Pompadour, Washington, DC: Opera Lafayette, 2023, 56-7.

[17] Vivienne Westwood, “Vivienne Westwood on the Wallace Collection,” YouTube video, 5:17, October 1, 2009, https://youtu.be/v_-XK5WaZEo.

[18] Savill, in discussion with the author.

[19] Saville, in discussion with the author.

[20] Savill, correspondence with the author.

[21] Savill, correspondence with the author.

[22] Savill, correspondence with the author.

[23] Fury, Westwood, and Kronthaler, Vivienne Westwood Catwalk, 348, 361.

[24] Savill, in discussion with the author.

[25] “Through the political looking glass,” British Vogue, 16 November 2007, https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/through-the-political-looking-glass, accessed May 25, 2023.

Cite this note as: Robert Wellington, “Vivienne Westwood’s Eighteenth Century,” Journal18 (June 2023), https://www.journal18.org/6864.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.