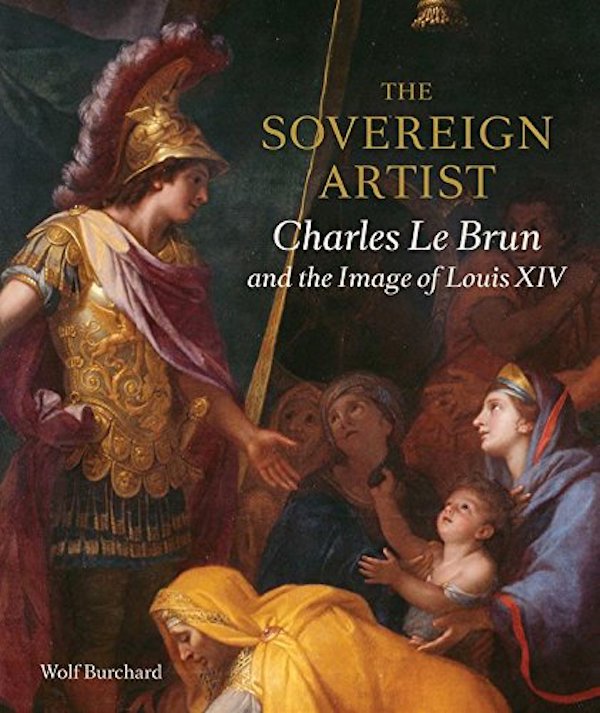

Wolf Burchard, The Sovereign Artist: Charles Le Brun and the Image of Louis XIV (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2016), 287pp.

This impressive new study of Charles Le Brun (1619-1690) argues that the artist was not only responsible for the elaboration of the image of Louis XIV as the absolute monarch, but that he constructed for himself a parallel role as the “sovereign” of the arts in seventeenth-century France (31). There is plenty of evidence to support this claim, at least if his official appointments are anything to go by—First Painter to the king; director of the Gobelins tapestry manufactory; surveyor of the king’s drawings and pictures; chancellor, rector, and from 1683, director of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture; membership in the Académie royale d’architecture, consultant to the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres; the list goes on and on. Indeed, his influence was so absolute that it led his first biographer, Claude Nivelon, in an analogy that would have been lost on no-one, to compare Le Brun to a sun that “warmed the fine arts of painting and sculpture with his beautiful mind and his example (19).” It is the nature of this example that Wolf Burchard addresses in this well-researched and beautifully-produced book, in which he argues for a coherence and unity in Le Brun’s thought and art that reflected his ability to oversee the unity of the vast decorative schemes he undertook on behalf of the king.

Anthony Blunt’s celebrated characterization of Le Brun as “the dictator of the arts in France” causes Burchard some problems (19, 31). It is not that examples of a dictatorial authoritarianism are absent from Le Brun’s biography. From his battles with fellow academician Abraham Bosse, forced to withdraw in 1661 over what Le Brun regarded as Bosse’s heretical views on the value of perspective, to the fraught theoretical debates on questions as recondite as how many camels Poussin should have included in his Eliezer and Rebecca at the Well of 1648 (the correct answer was none, as Poussin had wisely anticipated), Le Brun’s authority was constantly in play. But while Burchard argues for a close analogy between the authority of Louis XIV over France and that of Le Brun over the arts, he nevertheless takes exception to Blunt’s terminology on the grounds of political anachronism: “Far more than merely implying the traits of an omnipotent controller who may indeed have ‘dictated’ the output of French visual art production, the term strongly intimates coercion, even despotism and oppression (21).”

Burchard’s characterization of a Le Brun whose authority was absolute but not dictatorial has not always been in vogue, and in some circles still isn’t, but it does have the advantage of acknowledging an artist whose influence was omnipotent in state-sponsored artistic circles, while stopping short of the prejudice that he was the “dictator of the arts.” Instead, Burchard is primarily interested in examining the way that Le Brun’s acceptance of this plurality of roles—painter, designer, decorator, architect, spokesperson, advocate, enabler—allows us to draw a comparison with the absolutism of Louis XIV, whose many functions were united under his celebrated aphorism, “L’État, c’est moi” (I am the State). Could a painter also be a decorator and designer and functionary without losing credibility? Was the architect superior to the painter, or vice versa? What of the status of drawing, did it tie the arts together under a common denominator as the foundation of the arts of design (dessein/disegno), or sunder them into different disciplines? These questions would have mattered to Le Brun, who, more than most, must have acutely felt his artisanal origins (his father Nicolas Le Brun was a master sculptor and member of the Maîtrise or guild that resolutely opposed the creation of the royal Academy). An engraving by Sébastien Le Clerc, Charles Le Brun Ruling over the Visual Arts (79), shows Le Brun in this role of omnipotent controller of the fine arts. The artist is portrayed, dividers in hand indicating his liberal not artisanal status, pointing to an architectural elevation of a classically-inspired façade. To his left, and occupying most of the right half of the engraving, a figure, reminiscent of an allegory of painting, works at a large canvas depicting a noble rider who may well represent Louis XIV, leading his troops into battle. Le Clerc’s engraving reminds us that Le Brun was first and foremost a history painter, and that the Academy, in addition to being a bastion of royal privilege, was designed to represent this most elevated of genres against any imputation of servility or link with the manual trades. As Burchard notes, for Le Brun painting needed to be associated with ideas, and the debate that erupted in 1671 when Gabriel Blanchard delivered a lecture, “On the Merit of Color,” forced the First Painter into a call-to-order to define color as secondary and dependent on drawing, the latter long held to characterize the intellectual side of pictorial representation (86-87).

History paintings were not representations of reality but imaginative transcriptions of significant moral lessons, and as such the only kind of painting appropriate to the representation of Louis XIV, not as he was, but as he wanted to be seen. Le Brun’s understanding of the genre is evident in another painting discussed by Burchard, The Queens of Persia at the Feet of Alexander the Great, painted in 1662 at Fontainebleau, reputedly in the presence of Louis XIV (93-104). The painting evoked precisely what Louis required, a direct comparison between his rule and that of Alexander (Le Brun later produced a series of cartoons, in fact vast paintings that today hang in the Louvre and at Versailles, to be used as models for Gobelins tapestries). As Burchard points out, this involved two kinds of authority—first over the artisans working in the many establishments fabricating the image of the king, and second, the ability to produce works that stood for the authority of Louis XIV (152). It is a sign of Le Brun’s flexibility and skill as an artist that he was able to defend a rigorous theory of painting as First Painter, while successfully undertaking a great deal of work designing and supervising the making of tapestries, carpets, and other furnishings for Versailles.

This flexibility and skill culminated in his design and supervision of the celebrated Escalier des Ambassadeurs at Versailles, built between 1672 and 1679, and, sadly from the point of view of our understanding of one of the most important public spaces at Versailles, demolished in 1752 under Louis XV. The subject of Burchard’s final chapter, “On the Highest Rung,” the staircase brought together Le Brun’s talents into an unsurpassably opulent whole, demonstrating, if further demonstration were necessary, that his skills as artist, designer and superintendent of public works were vital to promoting Louis XIV’s visual image. Its purpose was to overwhelm and dazzle the eye through the deployment of an abundance of rich ornamentation and figuration that served to demonstrate the ascendant authority of the king, whose bust presided over the central part of the staircase as painted figures looked down at the visitor from trompe l’oeil balconies.

Burchard’s book is particularly valuable in emphasizing the importance of Le Brun’s work beyond the confines of history painting, showing the artist to be a talented synthesizer of design elements who understood that good design far exceeds its mere association with ornamentation and décor to address qualities that have the potential to speak as eloquently as pictorial imagery. And whereas Le Brun has been, for the most part, the object of partisan bickering that has tended to pass over his achievements in favor of casting him in the role of villain in the debate around the aims and direction of the arts in seventeenth-century France, Burchard has shown this most versatile and industrious of artists could put his wide-ranging talents to work for the century’s most ambitious monarch while manufacturing the image of the absolute artist along with the image of the absolute ruler. Finally, if Le Brun was not quite as sovereign as Burchard claims, then reconsidering the image of the artist in the interests of advancing not only the aims of seventeenth-century painting, but also those of the decorative arts that Le Brun did so much to foster, whether in emulation of his master’s absolutism or not, is a very good start.

Paul Duro is Professor of Art History/Visual Culture Studies at the University of Rochester, NY

Cite this note as: Paul Duro, “The Sovereign Artist: A Review,” Journal18 (November 2017), https://www.journal18.org/2323

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.