Over the century and a half of its existence (1648–1793), the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture amassed a collection of more than 15,000 artworks: paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, casts, and medals.[1] Its conceptual core was formed by reception pieces (morceaux de réception)—works that young artists submitted for examination to become full members of the institution. The collection also included commissioned portraits of the Academy’s patrons; paintings and bas-reliefs that were awarded the Prix de Rome, enabling prospective members to live and work in Italy; académie drawings of live models by students and professors; plaster casts of classical sculptures; and miscellaneous donated works of art, furniture, and unclassifiable objects (e.g., skeletons used in the teaching of human anatomy).

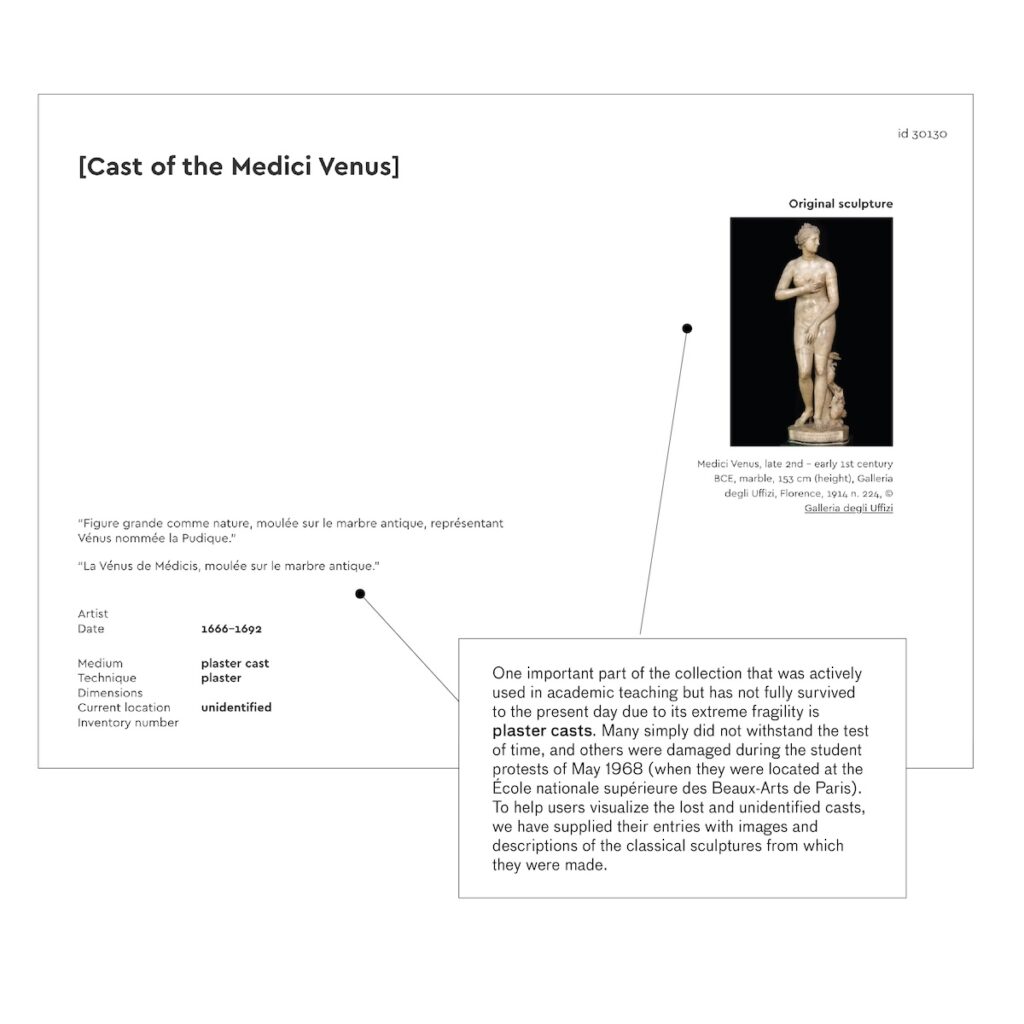

As almost all of the prominent artists of the old regime were members of the Académie royale, the collection united such iconic reception pieces as Antoine Watteau’s Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera (1717), Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s Ray (1728), and Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s Septimius Severus and Caracalla (1769). These and other examination works now offer valuable insights into the institution’s aesthetic values. Académies, plaster casts, and other objects used in teaching shed light on the pedagogical process, while commissioned portraits of the Académie’s patrons and donated works of art illuminate the personal networks behind it. Collectively, these objects show how the most influential art institution in eighteenth-century Europe viewed and positioned itself.

Together with the Académie, the collection changed its home numerous times, moving from the Saint-Eustache to the Hôtel Clisson, to rue Sainte-Catherine, and to the Palais-Royal. But for most of its history, from 1692 to 1793, the Académie’s collection was housed in the Louvre.[2] The hanging of the collection in the Louvre was a remarkable example of eighteenth-century curatorial work and an important “internal” counterpart to the Académie’s public display, the Salon. Unlike the Salon Carré, the main rooms of the Académie were accessible only to exclusive visitors, yet the works they contained served as major reference points for students and members of the institution, many of whom not only worked but also lived in the Palace.[3]

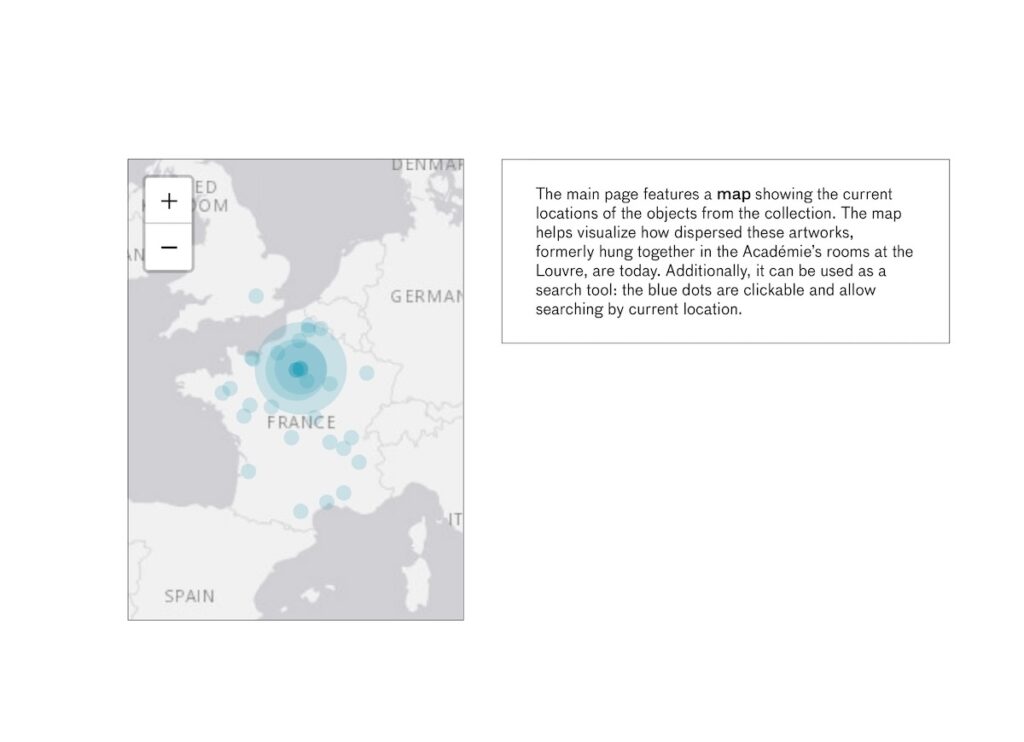

After the French Revolution, the art collection of the Académie royale was dispersed and today is shared by the Musée du Louvre, the Château de Versailles, the Beaux-Arts de Paris, and many other museums in France and worldwide. Working with a team comprised of myself, Anne Klammt (Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarianism Studies), Moritz Schepp (Wendig OÜ https://wendig.io), and Markus Castor (DFK Paris), we have created a database that establishes the objects that were originally in the collection and shows where they are preserved now.

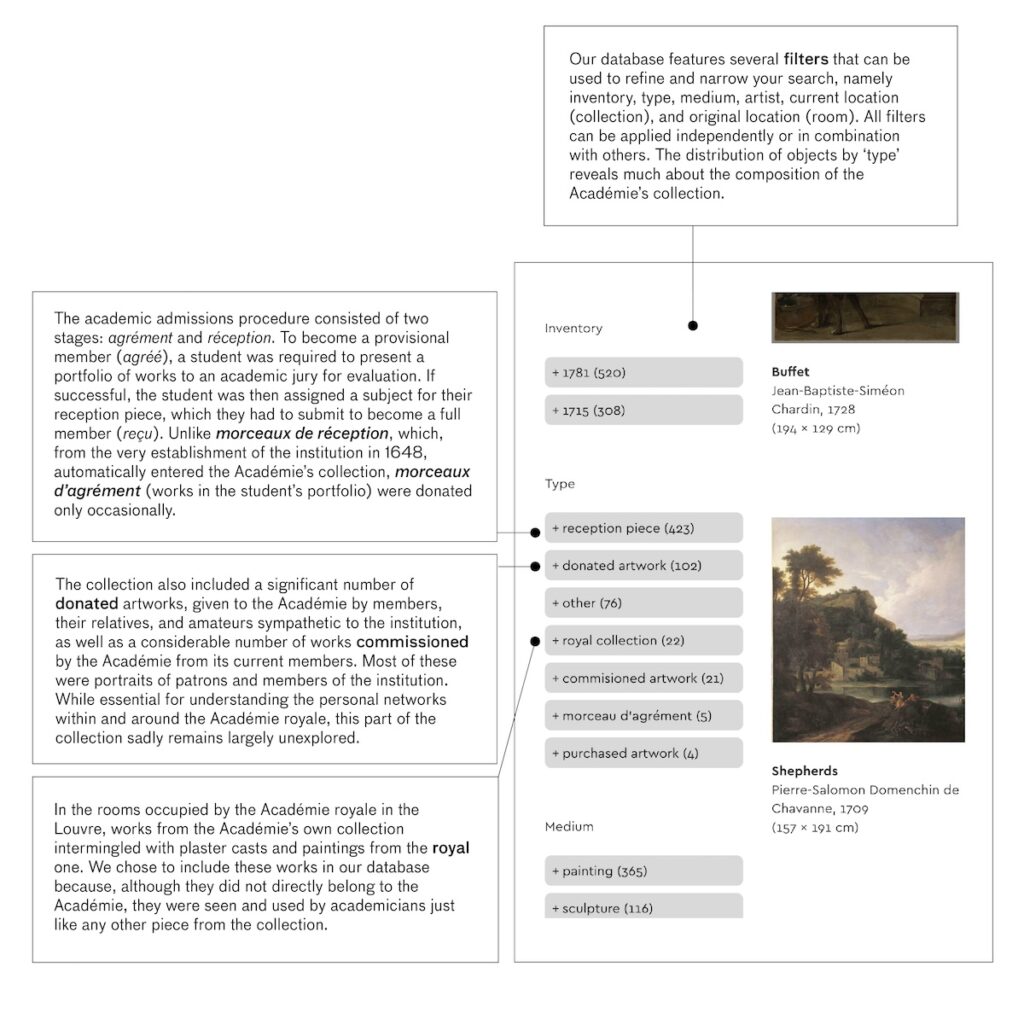

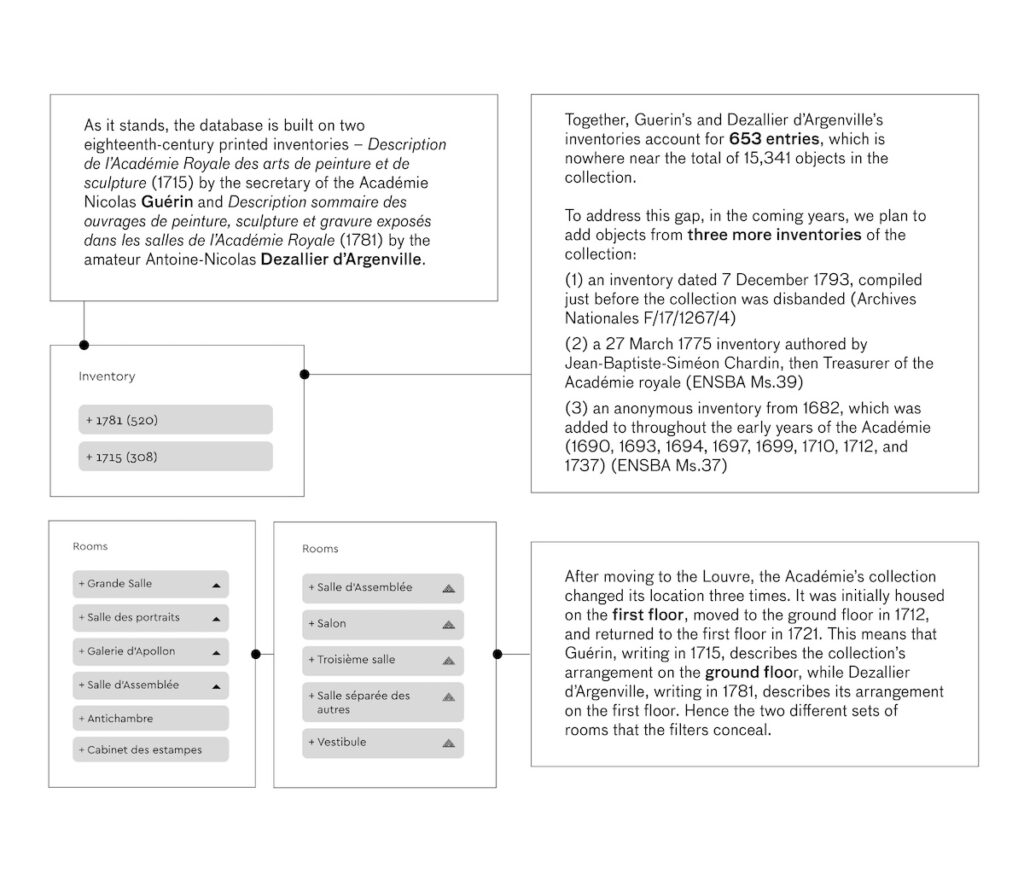

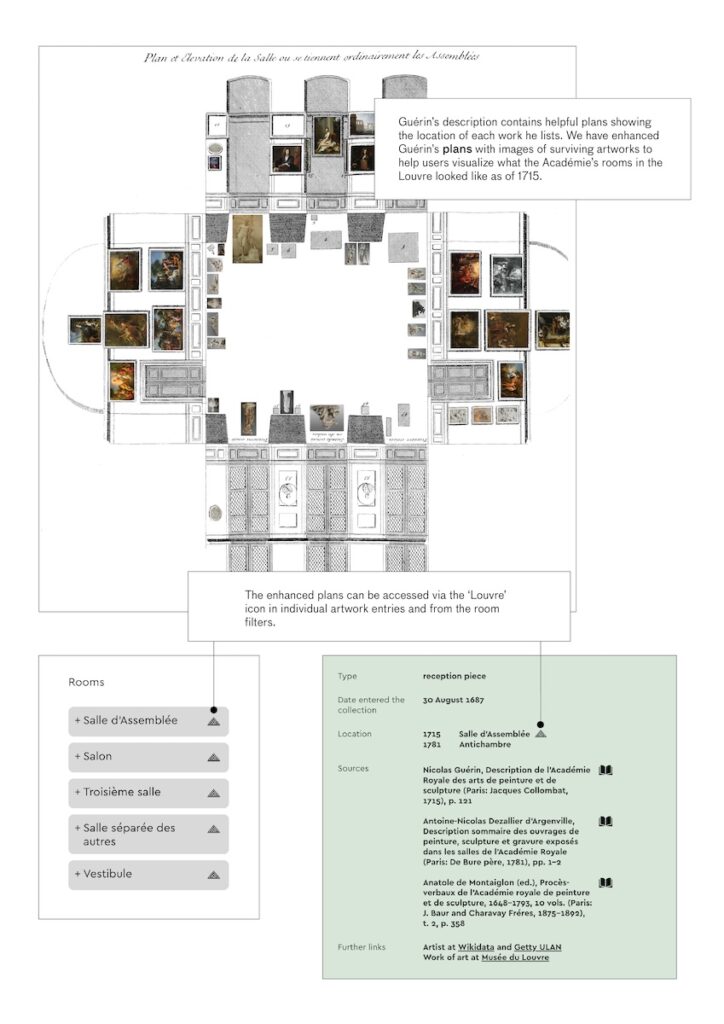

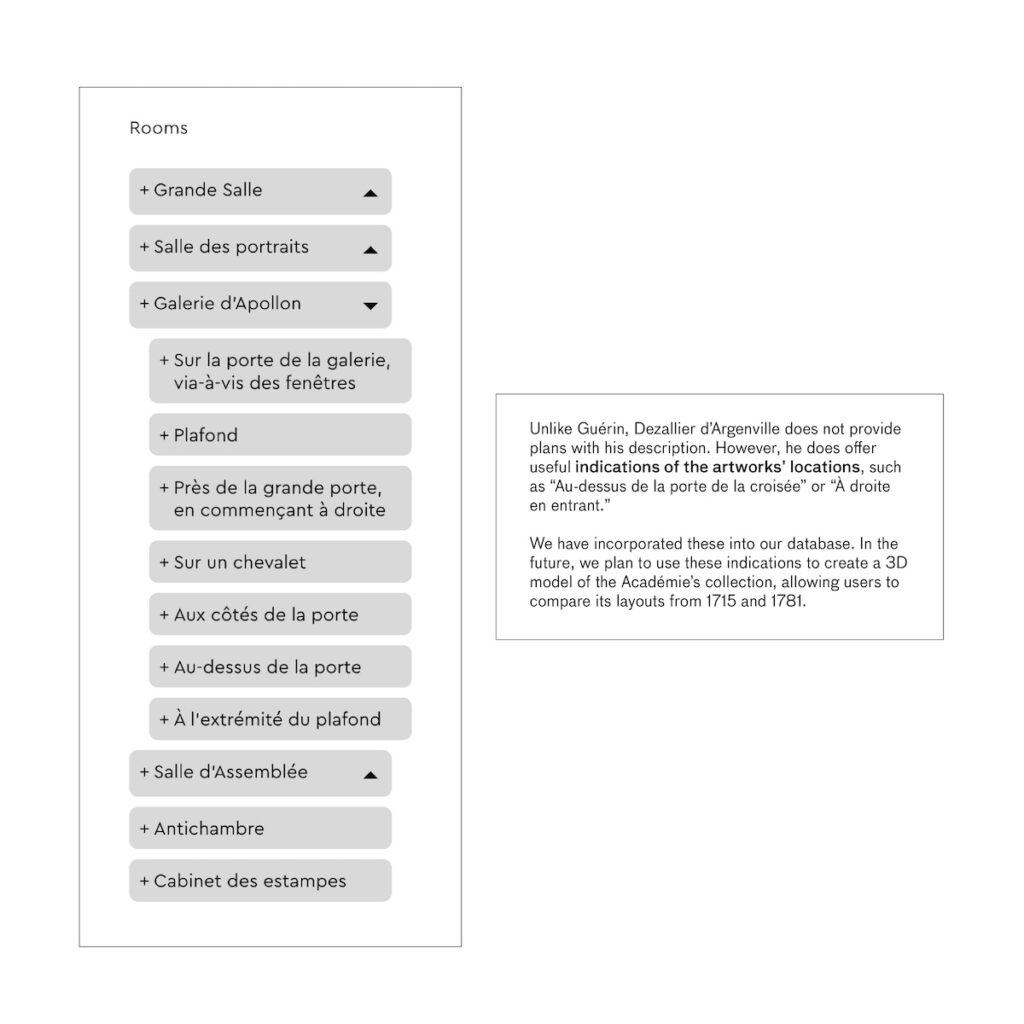

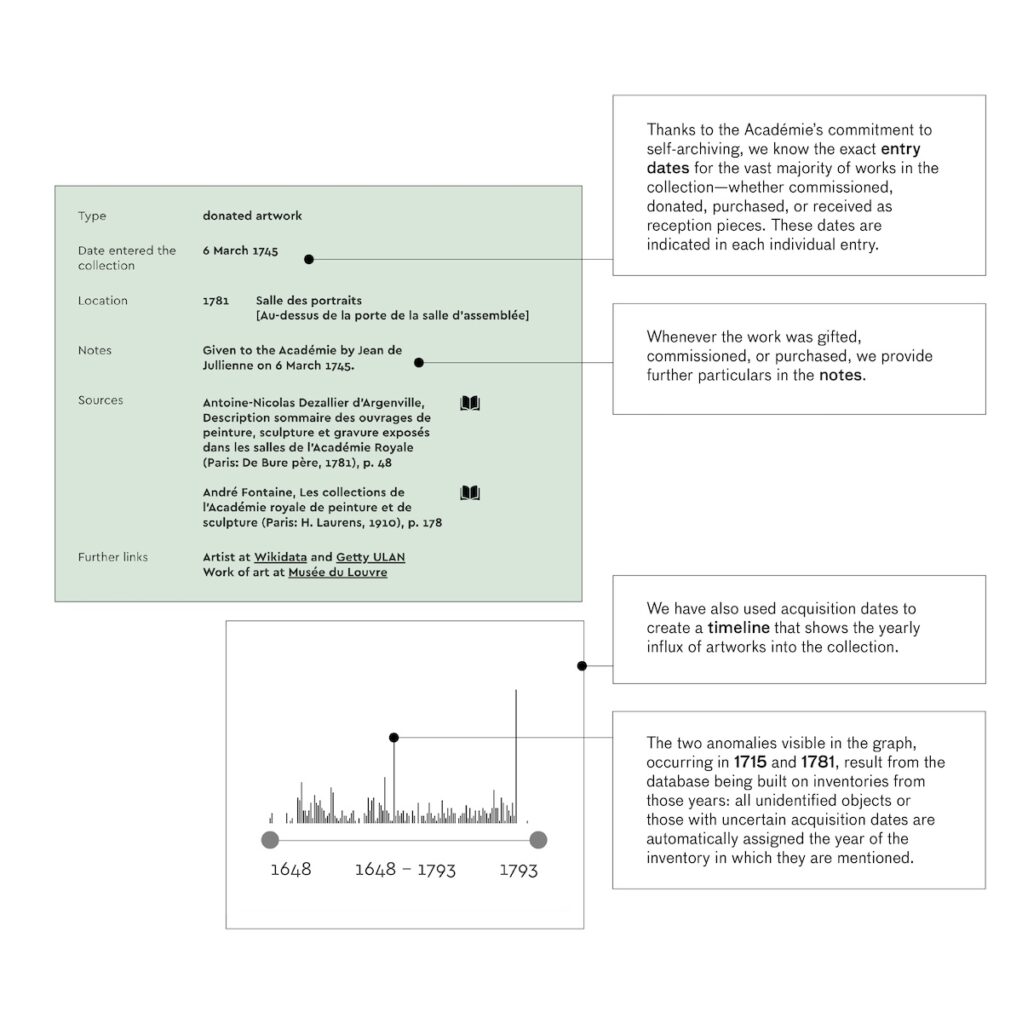

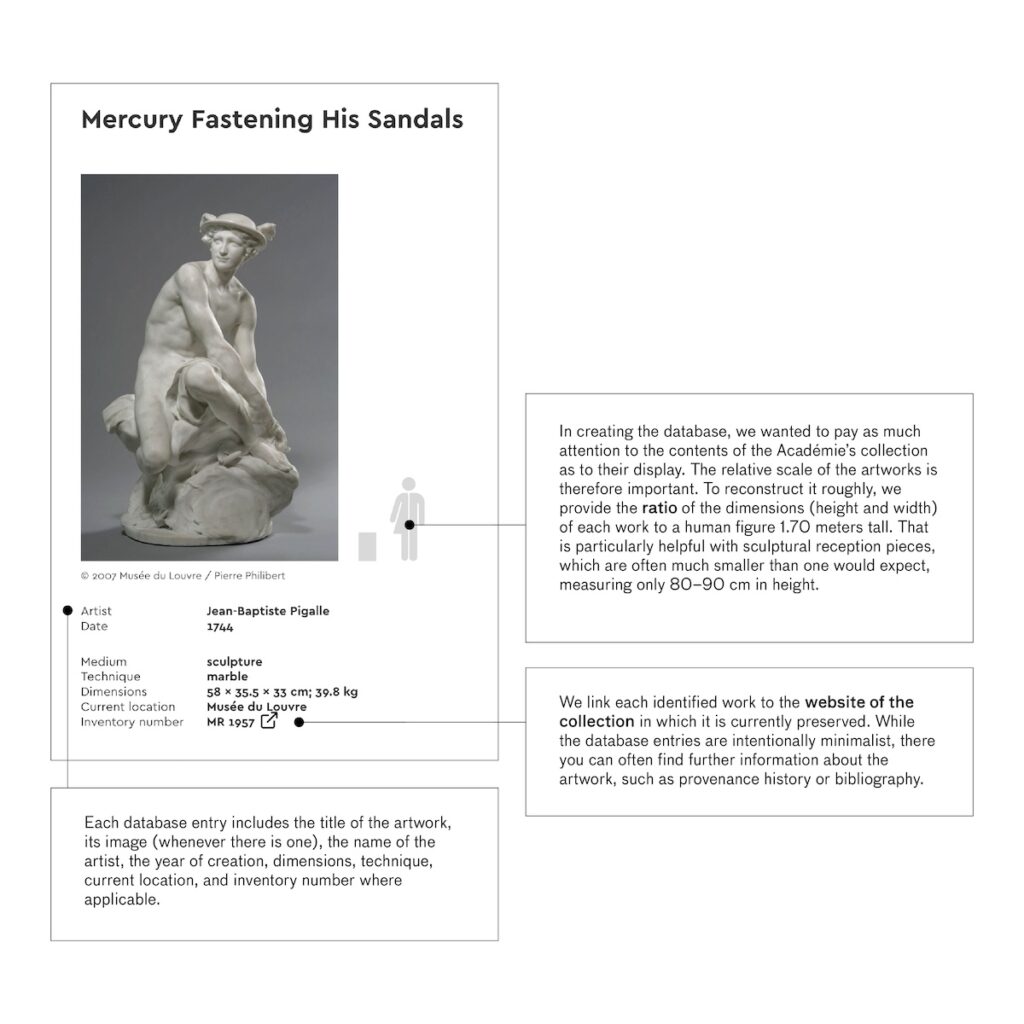

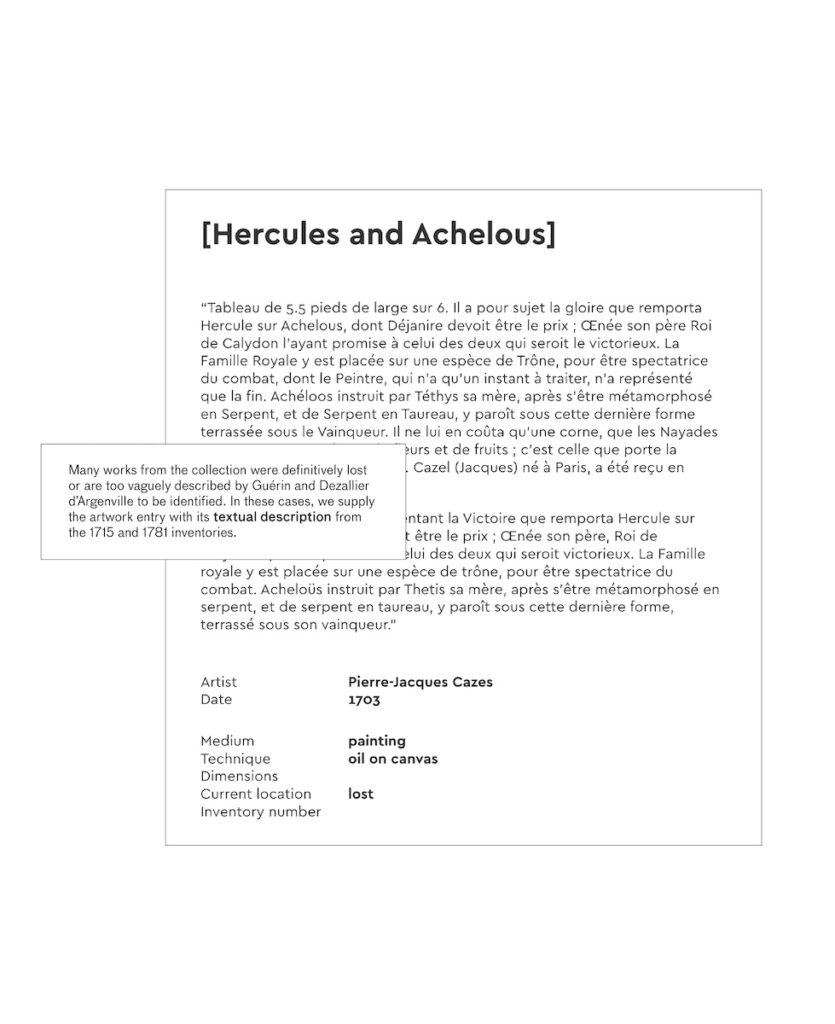

Aiming to foster interest in this unique yet almost entirely overlooked collection, the database will also serve as a useful tool for any historian of ancien régime art, regardless of their specialization.[4] What follows are some notes and graphics related to the database, detailing its functionalities, the conceptual choices involved in its creation, and our future plans.[5] Our database is very much a work in progress, and we welcome any feedback, corrections, or comments at the project email address ca-royale@dfk-paris.org.

Sofya Dmitrieva is a Research Assistant in Digital Iconography at the Voltaire Foundation

[1] The 9 December 1793 inventory of the collection, compiled after the dissolution of the Académie, lists 15,341 works, reprinted in André Fontaine, Les collections de l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Paris: H. Laurens, 1910), 269.

[2] Geneviève Bresc-Bautier and Guillaume Fonkenell, eds., Histoire du Louvre, 3 vols., vol. 1: Des origines à l’heure napoléonienne (Paris: Fayard, 2016), 448.

[3] More on the subject, see Jules Guiffrey, “Logements d’artistes au Louvre,” in Nouvelles archives de l’art français (Paris: Charavay, 1873); and Katie Scott and Hannah Williams, Artists’ Things: Rediscovering Lost Property from Eighteenth-Century France (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2024).

[4] The only comprehensive study of the Académie’s collection, André Fontaine’s Les collection de l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Paris: H. Laurens, 1910), is now over a century old. An important step towards the recognition of the collection in recent decades was the 2000 exhibition Les peintres du roi, 1648–1793, which brought together many works from the collection for the first time since 1793 and laid the groundwork for further research. See Les peintres du roi, 1648–1793, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000), and especially Udolfo van der Sandt’s essay on pp. 69–76. Morceaux de réception, the basis of the Académie’s collection, were the focus of William McAllister Johnson’s 1982 exhibition dedicated to engraved reception pieces. See French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture Engraved Reception Pieces, 1672–1789, ed. McAllister Johnson, exh. cat. (Kingston: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 1982); and Sharon Boedo’s 2005 doctoral thesis (Sharon L. Boedo, Reception and Membership at the Académie royale de peinture et sculpture, 1648–1793, PhD diss, Cornell University, 2005). Most recently, Hannah Williams published Académie Royale: A History in Portraits (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2015), a monumental investigation into the reception works of portrait painters. Important insights into the collection can also be gleaned from recent research on the Académie royale as an institution, most notably Christian Michel’s L’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (1648–1793): la naissance de l’École française (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 2012) and Gudrun Valerius’s Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture 1648–1793: Geschichte, Organisation, Mitglieder (Norderstedt: Books on Demand GmbH, 2010), see especially pp. 207–227. To address the century-old gap in the study of the collection, we are currently working on a multi-authored volume, The Académie Royale Art Collection: Vol. I Reception Pieces, featuring contributions by Melissa Hyde, Mark Ledbury, Hannah Williams, Catherine Girard, Susanna Caviglia, Yuriko Jackall, Alden Gordon, and Antoine Gallay. The volume is in the final stages of production and will soon be published in the DFK Paris x University of Heidelberg open-access series Passages online.

[5] I would like to thank my dear friend Nikolay Filippov for designing the notes for me.

Cite this note as: Sofya Dmitrieva, “The Art Collection of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture: Notes on the Database” Journal18 (February 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7671.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.