On October 16, 2019—two hundred and thirty years to the day she was guillotined—a new exhibition devoted to Marie-Antoinette opened at the Conciergerie in Paris. “Marie-Antoinette: Metamorphoses of an Image” presented a panoply of pictures of the doomed queen, from nostalgic celebrations to pornographic tirades, from a plumed Miss Piggy à l’autrichienne to the Japanese manga La Rose de Versailles. Trading on her notoriety and the proliferation of images that Marie-Antoinette herself cultivated, the Conciergerie exhibition is, predictably, salacious as it celebrates its subject’s uncanny prescience in crafting a media persona: “…the final ten weeks that saw the most dramatic moments experienced by the queen in the ‘corridor of death’, during her trial by the Revolutionary Tribunal.”[1] Marie-Antoinette was suddenly back in Paris, as if she’d never left.

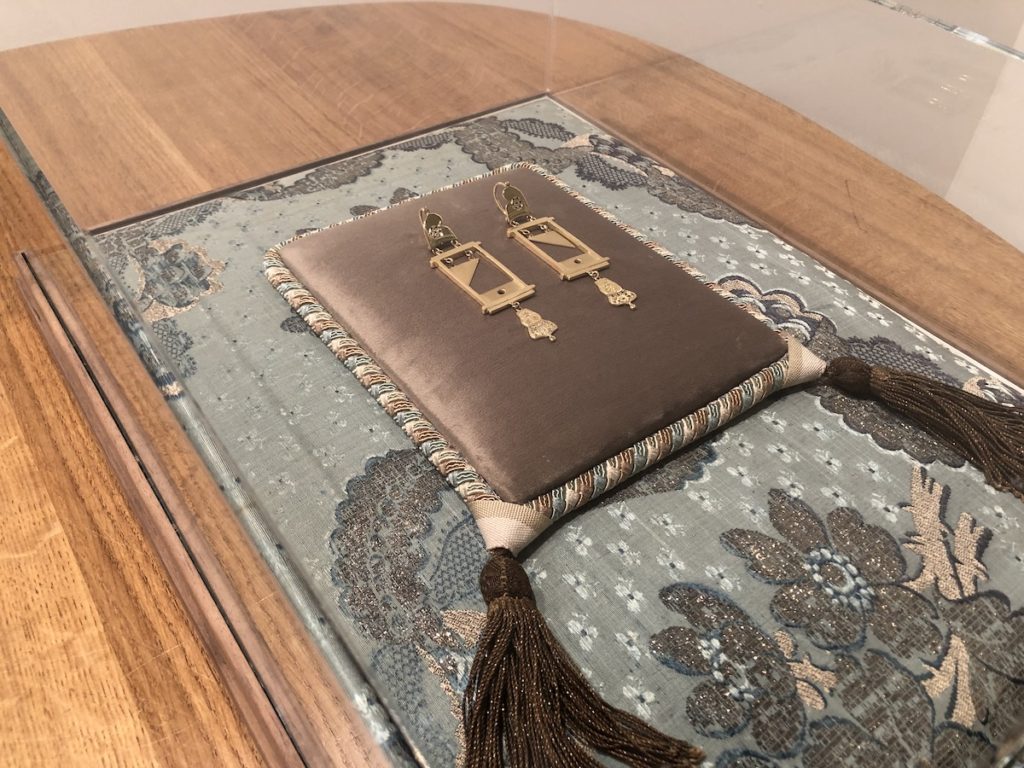

A perhaps less expected venue for her royal highness opened the very same week at Paris’ revitalized contemporary art fair in the Grand Palais. At FIAC, the contemporary artist Simon Fujiwara (b. London, 1982) showed several pieces derived from a new body of work that he has been developing around the figure of Marie-Antoinette. The series debuted this summer in Japan, a country as fixated on her as Paris appears to be this fall. There, at Tokyo’s Tara Nasu Gallery, Fujiwara staged The Antoinette Effect, an exhibition that anticipated—but clawed much deeper into—the Conciergerie’s investigation of the media cult around ‘Toinette. Certain elements from the show later traveled to Paris. An edition of bronze tears, for example, rendered from precise measurements the artist had taken of the queen’s “tears” in her former prison cell. Or a ghoulishly gilded set of giant guillotine earrings with the queen and her consort’s decapitated heads dangling below, based on anonymous 1794 originals (Fig. 1). The manifold parallels that these objects generated—between the gleam of democracy embodied by the guillotine, and the sheen of profit to be made through the commodification of the self-as-image—sliced gracefully through both the art fair and the Conciergerie show. They hinted at the still throbbing node that links a contemporary moment obsessed with self-mediation to the origins of mass commercial culture in the era of the French Revolution.

I caught up with Fujiwara in his Berlin studio to ask him about the creation of these objects, his interest in Marie-Antoinette and the commercialization of the Revolution, and their connection to our own image-saturated, autobiographical moment.

Sasha Rossman (SR): I was thrilled when I saw your appropriation of those guillotine earrings—your entire installation seemed to build so many complex connections between this powerful political event cum commodity display and today’s world in which political revolution seems so beyond reach. Can you tell us how you developed these works and how your interest in Marie-Antoinette came about?

Simon Fujiwara (SF): My interest in her began in architecture school. One of the courses in my first or second year was about nature and the garden, and one of the lectures included the Hameau de la Reine. It blew me away to think that in the 1700s someone had this vision of creating a complete fantasy version of a farm that existed just outside the gates, but a curated one in which you would dress up and play in costume. I just thought this is so now, this is what we’re all doing: living out a post-9/11 rustic fantasy of everyone going back to having wooden tables, organic food. I was seeing this parallel with Marie-Antoinette and I was like, “she is a fucking genius this woman.” Everything that she was chided for and everyone thought was so decadent, is something that became the desire of everyone. A democratic desire.

I thought, then, that she was having this early feeling of being trapped in the modern world, and then I thought, well, let’s imagine the process of her life. She’s coming into the French empire at its peak of [material culture] production…she walks into Versailles and there are just perfectly finished oil paintings, perfectly gilded frames, the floors are parquet marble inlay. She knows nothing, she doesn’t know how to make anything. It’s like us [takes out phone] these are the tools we use every day—I don’t know what’s inside my iPhone.

I feel the same, like, now I need to go for a walk in the forest because I can’t deal with the world of products that I live in. Her reaction is, “I want to go back to nature, I want to smell cow shit and pick dirty eggs out of a basket and play the role, but I just want it to be a walk away.” Which is our equivalent of an EasyJet flight. Thinking about this in terms of how democracy was then formed and how we now live in a period where we all want this little similar serotonin kick of being able to escape from something. Of course, now it’s to the detriment of the environment, but I think it was a genuine cry for help. I became fascinated by her for that reason. I had seen the films, I’d read vague biographies and things. Nothing interested me.

SR: What did you find missing in these mediations (like Sofia Coppola’s)?

SF: The movie cast her as this child who did not know what she was doing; it wasn’t about the outside world and how she fit into what was happening. Whether she was like that or not is not up to me to say, but the historical documents show that consciously, or unconsciously, she was very good at manipulating, and very aware of it. That is partly because of the proliferation of images of her. I think people say “well she was so vain,” but she was the first person who was really famous. Everyone knew what she looked like, so then of course she’s going to be like, “well this dress I’m wearing today is potentially going to be seen by a lot of people.” Versailles was open to the public at that time; the court had to be this open stage to the public. So this was an early tourism thing and people would come to see her, or the image of her.

Ultimately what fascinated me about Marie-Antoinette is that she emerged at a point where the modern world and image culture that we live in took off. Of course, there are threads of this in all ages. It was a revolutionary moment and it’s not like everything changed, but revolutions largely come with new technologies. I’m not in any way an expert on what was happening around it, but what caught my eye with Marie-Antoinette was complex. I was dealing with several female figures and she fit into a particular profile of femme fatale victims that were deemed too successful, became too close to an image, that ultimately had to be destroyed.

SR: How did the show come to fruition in Japan?

SF: I developed the show for Japan because Japan is obsessed with Marie-Antoinette, it’s their gateway to looking at France. It’s because she’s a cute, photogenic symbol, such an image. The Japanese can really get on board with things that have a clear visual narrative, where the aesthetic runs through to politics. They’re also a kind of violent nation, so they love her death. In Japan it’s like the cherry blossoms, a beautiful blossoming thing that is killed in its prime.

Because I’m half Japanese I have a very critical view towards it, but a problematic view because I desperately want Japan to modernize its thinking. I want it to become more international—globalized. Because being gay, being trans, being black, being white, would just be so much easier in Japan; it’s a monoculture. I think because of their monocultural ways they can hyper-focus on Marie-Antoinette in this completely exoticized way. So, I really wanted to make an exhibition about the thing that they love the most, that speaks about the process and steps as to why she’s become what she has, and why they consume her—as a mirror to it. They found the exhibition incredibly brutal. When I read the Instagram posts, the commentaries were very astute. People were quite moved and shocked by it. They really understood its relation to contemporary society.

SR: Can you talk more about what you ended up including in the show and how you came to make the objects?

SF: For years I knew about the Hameau, and one thing I loved was the animal zoo she had there. It had been taken over by a French animal rights charity who would bring in impoverished children from the banlieue to pet the animals. I just thought, North African kids coming to Marie-Antoinette’s fantasy farm 300 years later, as a charity project which funds the renovation of the farm. It was just too truthful, too appealing for me, this kind of twistedness. Then next door you have Dior paying for the restoration of her main living house (in the hamlet).

What are the economics behind this, who is supporting it, why do people want to regenerate it? So that was one avenue I started to take. But it wasn’t until I discovered these earrings—which are in the Carnavalet Museum—that it really felt like it gave me permission because it was something someone else had made about her. That’s generally where my work lies, in the mediation of things rather than trying to get to the source or the authenticity of that thing.

SR: How did you find them, were you googling guillotine merchandise?

SF: My research assistant and studio manager Maria Bartau presented the earrings to me, and I initially thought this is the sickest thing; it’s someone else capitalizing on her death. I realized very quickly that it is not the sickest thing at all. This is just the first step in a moneymaking industry around a woman that was completely criticized for being a big spender, but who is now earning so much money for the state of France. I had this tagline in my head which kind of guided the whole exhibition which was, “Marie-Antoinette, what she’s overspent in her life, she earned in her death.” Was she lavish, or was she incredibly canny? Without Marie-Antoinette, what is the symbol of France? She’s the face of it. She’s the human behind the door, certainly for Japan. It kind of reversed the way we think about her, putting her in a very cold brutal light of economy, and it’s about how at that time people would do that to her and today we do that to ourselves.

SR: It’s specifically interesting with the earrings because they were made for women to wear at the same time that women were being side-lined from the political sphere. The idea that somebody would take this image of her and the king and then turn themselves into a kind of macabre manipulation of that image becomes an interesting way of dealing with how you’ve been marginalized. To have the earrings gleaming in the light right next to your neck: you’re daring those that have tried to force you from the public sphere to stare at you. Although on the surface the earrings look similar to other “guillotine” merchandise, they reveal themselves as much more multilayered. One can understand them not only as a marker of partisan solidarity, or as a tourist souvenir, but instead as a critical re-positioning of the female body into the male revolutionary gaze through the production of a new and magnetic self-image via fashion, or “feminine” ornament.

SF: Totally, and this is an anti-royalist statement, but you’re replicating their gold, and they’re incredibly ostentatious. This idea of merchandizing someone like Marie-Antoinette is something we know and our generation grew up with it, because we grew up with icons like Michael Jackson and Madonna. The classic trope around people like that would be—they’d do a documentary and say, “I just wanna be normal, I just wanna be human again.” Their quest was, “How do I go from being a brand back to a human?” But our quest today is “How do I get from a human to a brand?” The dream of the influencer is to turn everything they do into a market. “I’m not gonna eat breakfast, I’m gonna turn my breakfast into an object and make my life a series of objects that are marketable.”

SR: On a wooden table.

SF: On a wooden table. And so, this kind of spoke to me as an early idea of how we capitalize on people and try to make money. I desperately wanted the original earrings to be a mass-produced object because it completely fits with my narrative, but of course, as you know with every good detective story, the detective must try not to follow who they want the killer to be, but follow the real lead. So, I contacted the British jewelry designer Andrew Bunny and showed him the images, and said can we make a pair of these (Fig. 2)? I got photos from the Carnavalet and they didn’t have much information on them either, except for the date. As we were producing them, we came to the heads of Marie-Antoinette and King Louis and Andrew said, “for this we need to produce a stamping machine and that’s gonna cost ‘x’. If we hand chiseled them for one pair it would be much cheaper, but if you really want them to look like they’re stamped like a coin, this is how much it’s gonna cost.” So I was like, “we have to make a machine just to do these ones?”

Then a lightbulb flickered and I thought, “well, they would never have made one pair because they’re stamped. They produced a machine, that’s what it costs now and that’s what it cost then.” They were a mass-produced object, so that was a eureka moment. I call that active archaeology, or a participatory or productive archaeology where just by remaking something, you learn something about the past.

SR: It’s all part of a larger machinery, I mean, the guillotine is a machine as well.

SF: The guillotine is a machine and the stamp is a machine. So that really excited me, and that was what I pitched my whole exhibition around, the use and abuse of Marie-Antoinette.

This spun into a series of works, so as you enter the exhibition there’s this hyper detailed reproduction of the gates of Versailles, which were the gates that were toppled during the revolution. Highly symbolic, the people came and destroyed them and got into the palace (Fig. 3). They were lost, they were broken, and nobody knew what happened to them until a group of millionaire private funders paid eight million euros to have them rebuilt in 2008. Exactly the year of the Lehman Brothers financial crisis. The walls of Versailles going back up, in gold, and I thought this was so symbolic and perverse.

From there you start to see these bronze casts of tears that kind of come through the space (Fig. 4). These are a reference to the chapel at the Conciergerie, where Marie-Antoinette was imprisoned before her execution. During the Bourbon restoration, the restored monarchy turned her prison cell into a chapel and allowed the public to paint silver tears all over the walls like a monogram around the chapel.

I measured the tears and then I made hand replicas, almost like jewels that are cast in bronze, and they glint as this kind of deconstructive space where you’re looking at things crying. Another work is a reproduction of the supposed “last letter” of Marie-Antoinette. It’s just such an emotive document with these almost burn marks, and it’s said to be tear-streaked. One of my collaborators is a woman called Annie Atkins; she’s a document forger and Hollywood prop maker who won an Oscar for Grand Hotel Budapest. I asked her to reproduce this letter, but also to send me all the materials of how she would do it, so you see the quite cold production of this emotive thing.

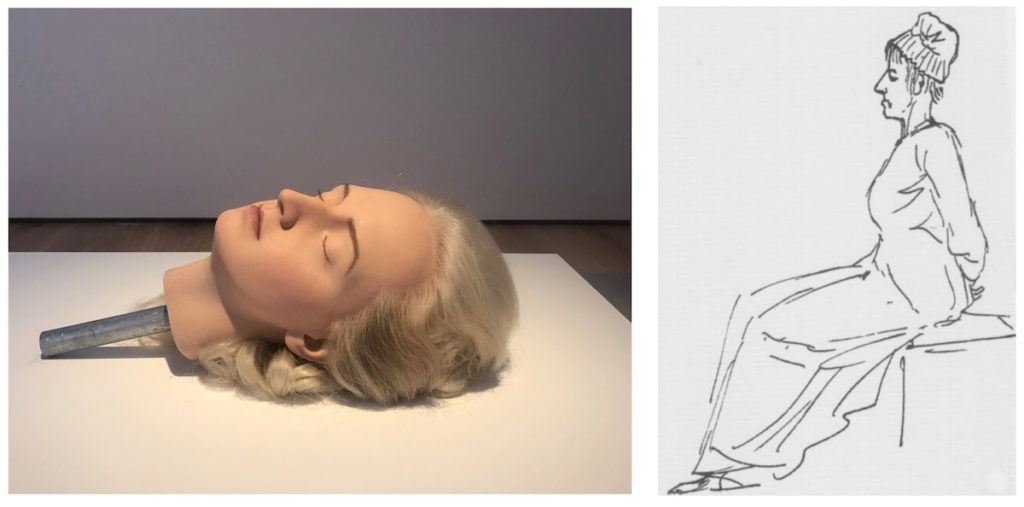

SR: What about the uncanny wax head?

SF: So I had built this series of arguments around how Marie-Antoinette’s been abused and used, and I guess the second centerpiece of the show became the wax rendering of her decapitated head (Fig. 5). It’s an un-naturalistic rendering you know, she has hair. We know she wasn’t decapitated with hair, it would’ve been cut (Fig. 6).

For another project [on Anne Frank], I was reading about Madame Tussauds and learned that the original Mme Tussaud had worked with Marie-Antoinette. It’s even rumored that she had lived in Versailles for eight years making wax flowers for the queen. The story goes that when the revolution came, Madame Tussaud was told she was going to be executed for her relationship with the royal family. She bargains her way to survival by saying, I will cast the heads of the nobility that you kill, and I guess the revolutionaries were like, well, we are kind of fascinated by celebrities, so let’s keep a record of them. She was bribing the revolutionaries, having their heads cast, making death masks of these people including her boss Marie-Antoinette. Then Madame Tussaud moves to London and needs to make money. So she opens her apartment on Baker Street, and shows all the heads of these French nobility that have been executed and people come and pay money.

It just amazed me that this kind of tacky, mass tourist venture that is Madame Tussauds, which our intelligentsia completely dismisses today, is rooted in this important historical period. It’s all linked together and though you have aspects of this kind of titillating tourism before, this dynamic really started to become economized and public in the eighteenth century.

SR: Is there an original, or how did you make it?

SF: There is an original. We based it on photographs, since the original is not on display anymore. There are many wax Marie-Antoinettes, there’s one in London, there’s one in Vienna, but they’re not good.

SR: Are they all casts of the same model?

SF: They look like they are, but I think they’re are so old by now, they’re 300-year-old wax casts. The problem with them now is she’s in this outfit with huge hair, she’s totally unrelatable to us and that’s always been the problem with Marie-Antoinette. So I wanted to make her look like someone you could have known. It was a kind of Hollywood-Disney tactic. Let’s use what we know about her, not lie, but let’s bring it to us. And what do we like now? We like no makeup, we like natural hair, that’s what makes people relatable and authentic. So let’s just take the powder off, let’s give the hair this kind of touch, let’s beautify her in an “authentic” way and that’s how I ended up designing Marie-Antoinette.

SR: But then of course she has this giant metal pole impaling her…

SF: Exactly, which is how the heads of Madame Tussauds figures are, so I like to think of her almost as a detachable sex doll head. That was actually inspired by a Japanese company called Orient Industry, and they produce hyper-real sex dolls. I went to the showroom where they allow one client at a time, and you have half an hour, and you have to buy something. There was just a cabinet full of heads and you can interchange the heads with the bodies, so when you get bored with your head you can just change it out for a different one. They are mechanically produced heads, so I kind of liked the fact that, with our Marie-Antoinette, her head could be interchanged but her body is missing: it’s just the head that is presented in a coffin-like vitrine. Next to her are some candles by Ladurée, these are their “Marie-Antoinette” candles. What I loved is that you first come in and you have this scent, and then you have this wax burning, and then you see her head in wax. And you’re consuming this kind of wax, it’s going inside your body. So the exhibition is kind of a loosely put together argument about Marie-Antoinette and the consumption of ourselves, or what we do, and why we want to do this.

SR: And you said that people reacted really strongly to it. Did people take selfies with the head like they take selfies with the figures at Madame Tussauds?

SF: I think it appealed to the dark, violent side of Japan. It is a country that is highly repressed, it’s very misogynistic, it’s hyper-capitalist, though in recent years more critical since Fukushima. They’re a country that knows about deep violence and fame, and social constructs. This exhibition was very much about social codes, money-making, all of the things I’ve described, but making it very elegant and beautiful and consumable. I have no desire to be close to Marie-Antoinette, or understand her thinking. I’m very clear that I’m re-appropriating her and re-using her to speak about what I want.

SR: One of the fascinating things about these works is that in their diversity, they foreground how now is such an eighteenth-century kind of moment, one that is striking in its destructive and constructive possibilities.

SF: Totally, I don’t know much about the eighteenth century, but the more I get to know about it, I think—it’s more like a hunch—that what’s happening now is nothing new. The way we complain about our over mediation and our fetishization and commodification is not some weird new impulse in humans; it’s been there forever.

Simon Fujiwara (b. 1982, UK) is an

artist living and working in Berlin. Sasha Rossman is a PhD candidate at the University of California,

Berkeley and a wissenschaftlicher assistant at the University of Bern,

Switzerland

[1] http://www.paris-conciergerie.fr/en/News/MARIE-ANTOINETTE-METAMORPHOSES-OF-AN-IMAGE (emphasis in the original).

Cite this note as: Sasha Rossman, “The Antoinette Effect: An Interview with Simon Fujiwara,” Journal18 (December 2019), https://www.journal18.org/4492.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.