In recent years, many American museums and their staff have staged revisionist interventions, urging general visitors and scholars to reframe, reimagine, and reinterpret European collections. In “Re-Presenting Art History: An Unfinished Process,” art historian Cristina Baldacci ruminates on the prefix “re-” as a hermeneutic tool strategically employed by curators to render histories palpable for contemporary global audiences, upend the art-historical canon, and reclaim and recontextualize distant narratives through a process of repetitive critical engagement between historic objects and modern beholders.[1] For the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, reconceiving the display of its permanent galleries and implementing collaborative curatorial practices for special exhibitions espouses the Thirteen Commitments it published in light of anti-racist demonstrations and protests in 2020. More specifically, the museum actively mobilizes Baldacci’s “re-” in the form of both a rhetorical device and a curatorial thesis, as evidenced by recent and upcoming exhibitions and installations, chief among them Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast (2022); the 2023 installation of Look Again: European Paintings 1300-1800; and the display of new interpretive labels in the Linsky galleries titled Reinterpreting Porcelain Figures (2022). The latter project is the subject of this review.

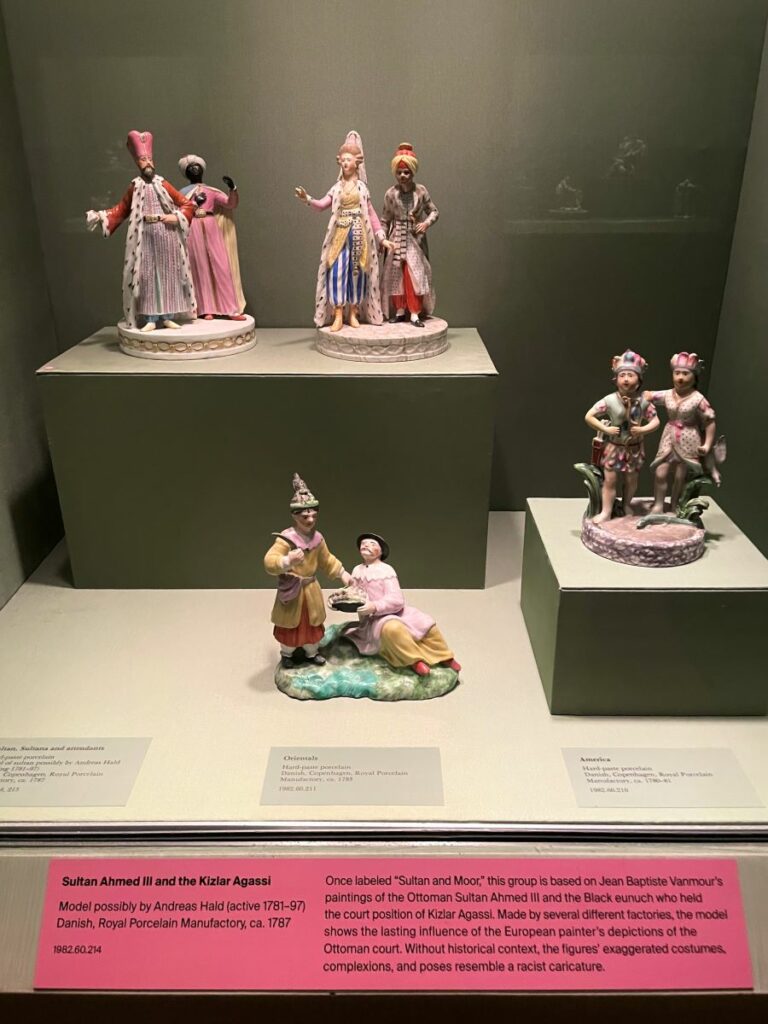

Eight new Pompadour-pink labels seize the attention of museum visitors roaming galleries 538 and 543, which house the collection of eighteenth-century porcelain that Belle Linsky (1904-87) donated to The Met following the passing of Jack Linsky (1897–1980). The didactics not only facilitate the reinterpretation of the porcelain figurines but also refashion a display that captures the presentation of the collection as it was encased in glass vitrines at the Linskys’ apartment. Facing up to the museum’s responsibility to public education and community engagement (and thus conforming to the International Council of Museum’s new museum definition announced in 2022), the additional commentary confronts the display of stereotypical, derogatory figurines without altering the installation’s original footprint or breaching the conditions of the gift, which stipulate that the collection must be exhibited in full and prohibit it from being paired with objects outside of the Linsky’s collection.[2]

Spearheaded by Iris Moon, assistant curator of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Art, and art historian Marlise Brown, the Linsky Project addresses critical themes of race, labor, colonialism, and global commerce that pervade European decorative objects from Germany, France, Russia, and Denmark. An introductory text mounted near each gallery’s entrance outlines the thesis of the intervention by posing a series of provocative questions: “Why collect porcelain in the past? And today? How does European porcelain, once the unquestioned pinnacle of luxury, reflect issues of race, labor, and slavery now?” A QR code provides museumgoers with access to an article by Brown detailing the development of the project and exploring how European aristocracies mobilized porcelain during the eighteenth century as a propagandistic token of hegemonic power.

The supplemental labels grapple with how political figures deployed the coveted “white gold” as diplomatic gifts and a means of solidifying social stratification. One of them considers a red stoneware portrait of Augustus the Strong (Meissen, ca. 1713), whose fixation with porcelain compelled him to establish the Meissen Porcelain Manufactory in 1710. Although diminutive in scale, the portrait renders the ruler with authority and power and contrasts starkly with the stereotyped depictions of non-Western porcelain figurines. Another autocratic figure, Catherine the Great, commissioned the Imperial Porcelain Manufactory at St. Petersburg to produce a series of Indigenous groups under the title “Peoples of Russia” (Russian, 1780–1800). As another label explains, a handful of these figurines are thought to be modeled on the depiction of Eastern European subjects from scientific expedition books, such as J.B. Le Prince’s Divers ajustements et usages de Russie dediés à Monsieur Boucher (1765) and Johann Gottlieb Georghi’s Description of All the Peoples Inhabiting the Russian State (1774).[3] Curators might wish to ponder retitling the series, bearing in mind a current movement within museums to reflect on constructions of empire by relabeling some art and artists previously identified as “Russian” as “Ukrainian” in response to the Russo-Ukrainian war.[4] Although the new labels for the Linsky porcelains identify individual figures by their respective Indigenous groups (including the Kamchatka and Samoyed), the figurines’ collective identity as “The People of Russia” remains haunted by historical and contemporary Russian hegemony. Given the fact that Jack Linsky immigrated to New York from northern Russia, and Belle Linsky from Kyiv, acknowledging the geopolitical tension between national identity and cultural heritage would have been more than appropriate.

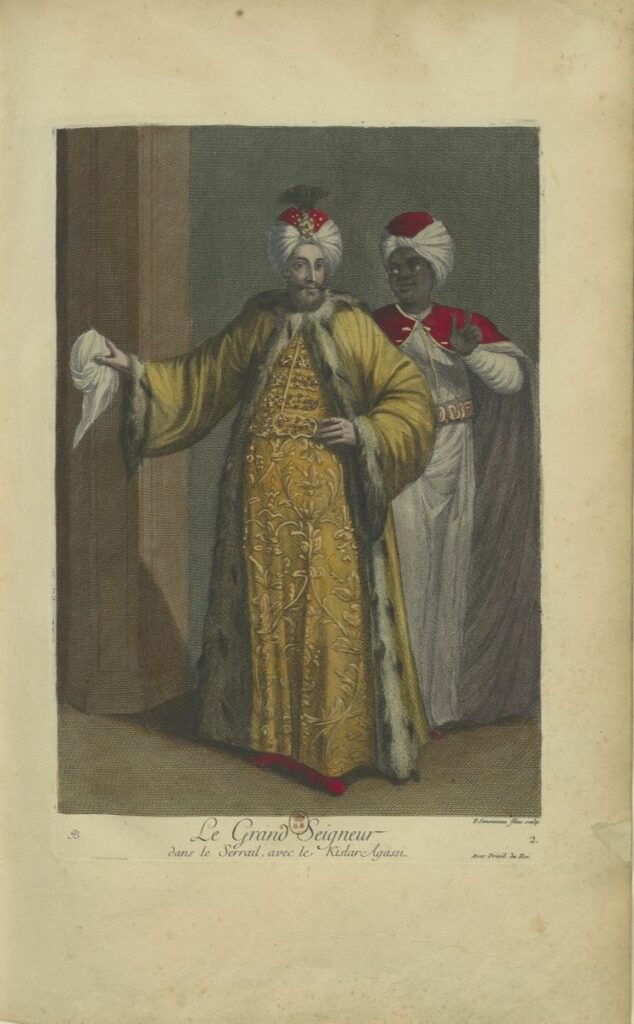

Another set of labels recontextualizes porcelain figures representing nations from the Near and Far East. One label introduces the European appetite for chinoiserie and notes how this eighteenth-century imitative practice metamorphosed East Asian people into grotesque, ornamental objects of amusement and aesthetic adoration, as exemplified by the distended belly, drooping earlobes, and sharply caricatured facial expression of the Nodding pagod (Meissen, ca. 1760) (Fig. 1). Empire and European expansion refract in the label for the Royal Porcelain Manufactory’s Sultan Ahmed III and the Kizlar Agassi (Danish, ca. 1787) (Fig. 2). While its reference to the influence of Jean-Baptiste Vanmour’s Recueil de cent estampes représentant les diverses nations du Levant (Paris, 1714) on such objects is not new, the label addresses how the act of disseminating and repeatedly printing proto-ethnographic representations of non-Western peoples opens up the potential for iconographic codes to ossify and become ingrained in the European visual lexicon as reductive stereotypes (Fig. 3). The Linsky Project could further expand upon The Met’s Thirteen Commitments statement with a label addressing the collection of “Dwarf figurines,” among them Dwarf as Turkish Pasha (Italian, 1745-50). In light of recent discourse on disability studies in art history, it is critical to differentiate between the technical process of scaling down figural representations of individuals into tabletop decorations and the exacerbation of physiological qualities indicative of a visible disability like dwarfism. It would be enlightening for there to be a discussion on the exploitation and history of gifting individuals with dwarfism as forms of entertainment among European courts, the manifold ways in which these individuals have been represented, and what purposes their presence serves as a visual device.

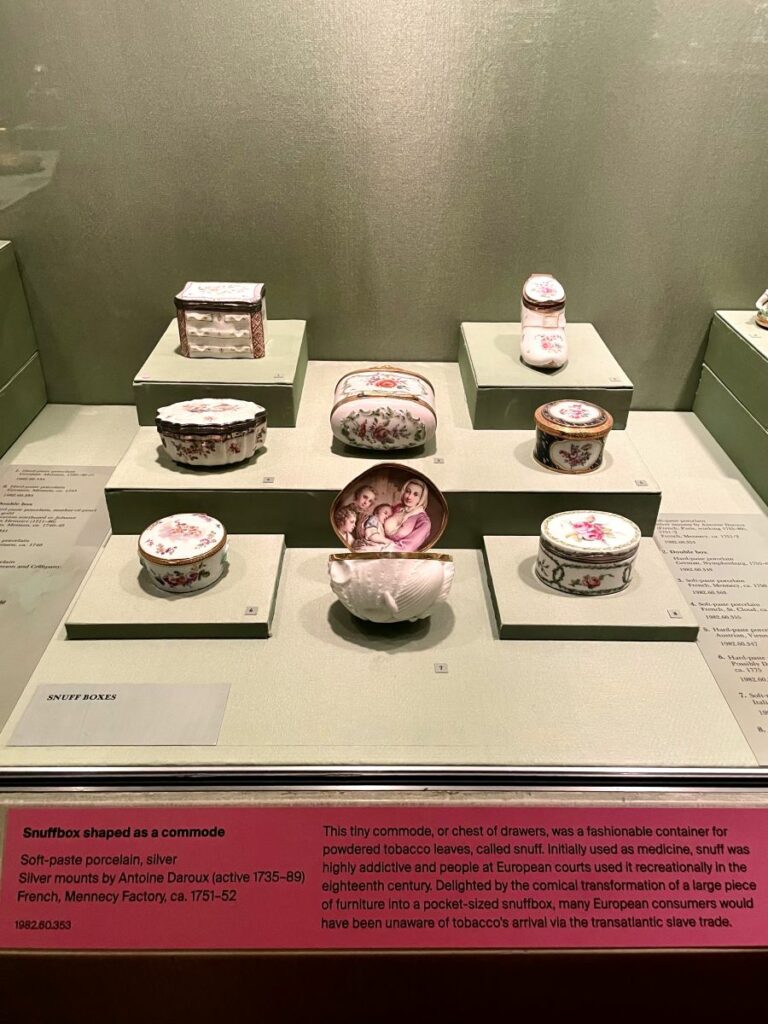

Procured through colonization, European leisure and luxury manifest in the group figurines of Couple drinking chocolate (Meissen, ca. 1744) and Hunters with Black servant (Höchst, ca. 1760) (Fig. 4). Yet, snuffboxes conceal labor exploitation via the transatlantic slave trade within the silky-white porcelain trinkets modeled in the shape of a miniature commode and slipper and decorated with floral motifs and garlands (Mennecy, ca. 1750-60) (Fig. 5). Even more disquieting are the blackamoor figures adorning Nymphenburg sugar boxes (Nymphenburg, ca. 1760). Tiny elements including fruit, precious jewels, and feathered headdresses amplify the exotic connotations of the Black figures. Curators missed an opportunity to interject an introspective historical reflection on the sugar and snuff boxes, like that from Jean Lecointe-Marsillac’s 1789 abolitionist publication: “We don’t drink a single cup of coffee [or ingest a single serving of sugar or snuff] in Europe that does not contain a few drops of African blood.”[5] Although the label intimates a connection to slavery, it does not explicitly address the opposing visceral experiences between those who harvested raw materials and those who consumed the fruits of that labor.[6]

Ideally, the intervention of the Linsky Project would benefit from a complete renovation of the outdated galleries, additional extended labels that drive a curatorial thesis, and perhaps a contemporary display. The condition that prevents the Linsky’s porcelains from being paired with other works from the museum’s collection ultimately stifles possibilities for contemporary collaborations as well as cross-media and cross-departmental pairings. A similar exercise has been conducted in a suite of galleries as a part of The African Origin of Civilization Initiative, where works from The Met’s collection of Oceanic Art are juxtaposed against objects across different curatorial departments. As we have seen in the case of the Sackler name’s dethroning, museum leadership is open to reassessing its walls and protocols. If anything, the proliferation of Baldacci’s “re-” ideology in art museums, grounded in repetitive reassessment, ought to convince reevaluations of the “in perpetuity” clause going forward. Although, the new labels have also been subjected to the amorphous timeline of “in perpetuity,” as curators do not have plans to take them down.[7]

The information in the Linsky Project is not new to the readers of this journal. But it is a radical change for the Linsky galleries’ eighteenth-century porcelain figurines, and one among a series of progressive operations reverberating throughout The Met’s permanent installations. Paralleled by the European Painting rehang that aims to engage robust dialogues between histories of class, gender, race, and religion, as well as the acquisition of a restored nineteenth-century portrait of an enslaved Black adolescent named Bélizaire in the American wing, perhaps we should imagine a shift in the Linsky galleries that would enable anti-racist curatorial practices to realize their full potential.

Noelle Yongwei Barr is the 2023-24 Semmes Foundation Fellow in Museum Studies at the McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX

[1] Cristina Baldacci, “Re-Presenting Art History: An Unfinished Process,” in Over and Over and Over Again: Reenactment Strategies in Contemporary Arts and Theory, ed. Cristina Baldacci, Clio Nicastro, and Arianna Sforzini, Cultural Inquiry, 21 (Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, 2022), 173–82, https://press.ici-berlin.org/doi/10.37050/ci-21/baldacci_re-presenting-art-history.html.

[2] Sarah E. Lawrence, email message to the author, September 5, 2023.

[3] J.B. Le Prince’s Divers ajustements et usages de Russie dedié à Monsieur Boucher (1765) and Johann Gottlieb Georghi’s Description of All the Peoples Inhabiting the Russian State (1774) are proposed sources for the porcelain compositions in The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984), 344, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/The_Jack_and_Belle_Linsky_Collection_in_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art.

[4] For more on the retitling of museum objects, see Robin Pogrebin, “Museums Rename Artworks and Artists as Ukrainian, Not Russian,” The New York Times (New York), March 17, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/17/arts/design/museums-relabel-art-ukraine-russian.html.

[5] “Non, je ne crains pas de le dire, on ne boit pas en Europe une seule tasse de café qui ne renferme quelques gouttes du sang des Africains.” Jean Lecointe-Marsillac, Le More-Lack ou essai sur les moyens les plus doux et les plus équitables d’abolir la traite et l’esclavage des Nègres d’Afrique, en conservant aux Colonies tous les avantages d’une population agricole (Paris: Chez Prault, 1789), vii, cited and translated by Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 224.

[6] Noémie Ndiaye makes a similar comparison with Matthieu Le Nain’s painting The Smokers, or the Guard (Le tabgie) (1643): “Such a painting suggests that Afro-descendants were associated in collective imagination with the addictive colonial goods that Parisians craved.” Noémie Ndiaye, Scripts of Blackness: Early Modern Performance Culture and the Making of Race (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022), 91.

[7] Iris Moon, email message to the author, October 4, 2023.

Cite this note as: Noelle Yongwei Barr, “Reinterpreting Porcelain Figures: A Review,” Journal18 (December 2023), https://www.journal18.org/7182.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.