Emily Engel, Pictured Politics: Visualizing Colonial History in South American Portrait Collections, Austin, TX, University of Texas Press, 2020, ISBN 978-1-4773-2059-4

Portraiture has provided intellectual fodder for art historical inquiry since the discipline’s inception and has bridged different geographic, material, and temporal fields. Dedicated to paintings by Renaissance titans, like Titian, nineteenth-century carte-de-visite photographs, and Francisco de Goya’s subtly subversive portraits of Spanish elites, among other topics, scholarship has treated portraiture’s ability to convey a sitter’s physical likeness, offer psychological insight, and provide a sense of dynastic continuity. Self-portraiture, from the examples by Rembrandt and Frida Kahlo to the infinite selfies posted on Instagram, has also offered stimulating subjects.[1] Scholars have assessed the bodily comportment of sitters and called attention to the garments and objects featured in portraits. Employing diverse methodologies, historians have sought to uncover the complexities underlying portraits and the relationships they generate. They have long studied portraits as an essential tool for disseminating ideas about individual identities and for promoting political ideologies.

Art historians specializing in the eighteenth century have contributed to the robust examination of portraiture, including the recent Journal18 volume on “Self/Portrait” (Fall 2019). The exhibition “Faces of China” (Royal Ontario Museum, 2013-2014; Kulturforum, 2017-2018) assembled countless portraits primarily from the Qing Dynasty to promote pioneering scholarship on this tradition in China. Scholars such as Heather McPherson, Malcolm Baker, Jennifer Germann, Amy Freund, and Magali Carrera, among others, have sought to expand the discussion of portraiture produced in eighteenth-century Europe and the Americas by considering the topic from new vantage points and through new interpretive lenses.[2] Despite portraiture’s status below history painting on the academic hierarchy of genres, it flourished, generating pictorial innovation and hybrid genres like the conversation piece. Artists increasingly depicted figures outside the traditional gamut of royalty, including actors, intellectuals, revolutionaries, and military heroes.

Emily Engel’s Pictured Politics, therefore, finds good company among scholarship devoted to portraiture. Specifically, Engel addresses official portraits depicting authority figures in the Spanish viceregal capitals, including Lima, Bogotá de Santa Fe, and Buenos Aires. Engel’s work coincides with recent work on colonial art, like Natalia Majluf’s writings on portraits of military figures in South America.[3] While religious art and casta painting have dominated Spanish colonial art history, including the exhibition “Painted in Mexico, 1700-1790” (LACMA, 2017; MET, 2018), portraiture is, as Engel’s book indicates, an essential component of art made in the Americas. As portraits produced for semi-public display and a communal political purpose, the images under discussion in Engel’s book are often overlooked in contrast to elite portraits created for private consumption. The repetitive nature of their iconography and format has, perhaps, prompted many scholars to avoid assessing their visual and political value. In addition, much of the literature dedicated to colonial art favors New Spain (Mexico), so Engel’s study fills an important gap in the scholarship on Spanish America.[4]

Produced by both indigenous and foreign artists working in the viceregal capitals, official portraits were typically displayed in semi-public spaces. Viceroys (the monarch’s representative at the head of colonial government) and others, like high-ranking ecclesiastical figures and members of the military, were protagonists in imperial governance. As such, their portraits, commissioned by local elites and visiting dignitaries, played propagandistic roles in the spaces in which they were displayed and helped maintain administrative continuity in the territories from one viceroy to the next, forming what Engel calls “portrait series” over the course of three hundred years of colonial rule. Engel proposes that because these objects visualize a sense of governing stability, they shaped the colonialists’ collective memory and identities and created a shared visual history of their experience. For example, indigenous elites in colonial Cuzco recalled their shared Inca past by including illustrious Inca figures in official portrait series of viceroys. Such an alliance, according to Engel, cemented their authority under colonial rule. Colonial rulers were viewed, then, as maintaining a certain level of control of local governance, with authority granted to them by both the Crown and their Inca predecessors. Such visual relationships depicted in the portrait series provided a vital visual connection to a shared indigenous past. As images displayed in the public collections of mostly municipal buildings, she argues, they possessed a direct political function in their depiction of local administrative figures who were the primary representatives of colonial needs. These representatives sought to negotiate their relationship to the monarchy and, simultaneously, exert agency in their respective colonial capitals.

Looking to postcolonial theoretical networks as interpretative models, Engel explores the origins of and shifts in the production of official portraiture as sites not only for critical engagement with Spanish imperial authority, but also for the “power dynamics between local elite and commoners as well as officials from across the Iberoamerican world” (3). Upending previous assumptions that these works merely reflected imperial ideology, Engel posits that they instead conveyed the nuances of colonial politics. She argues that they are “visual records of the negotiation of power” in that they “visualized the processes by which authority was exercised in the shaping of sociopolitical realities” (2-3). As images that helped record the history of colonial capitals, they often show an increasing sense of resistance by colonial elites to the imposed imperial structure and a drive for autonomy. Engel’s most significant claim is that they embodied local desire to generate the conditions from which colonists could possess ownership of a shared colonial past. As collections built over time in the viceregal capitals, they expressed individual agendas, fluctuations in local allegiances, and the ambiguities and inconsistencies of imperial rule. Engel astutely addresses official portraits from both a wide angle, discussing general characteristics, and with great specificity, pinpointing portraits that are emblematic of these larger practices of negotiation.

Engel organizes the material in five thematic chapters. She addresses the circumstances of each viceregal capital as artistic center and the types of official portraits that created this communal history. In the introduction, Engel provides key definitions and historical background about the founding of viceroyalties across Spain’s territories. These tools orient the reader, particularly the non-specialist. Lima emerges as an artistic, economic, and political powerhouse. Local politicians and civic and ecclesiastical organizations there employed portraiture effectively to negotiate authority within and outside the city. With the dynastic shift from the Habsburgs to the Bourbons in 1700, South American portrait artists responded to this change in power. As Engel shows, this period inspired a reevaluation of local authority within the Spanish empire that both aligned itself to the Bourbons and promoted the interests of a community diversely constituted by indigenous and colonial elites. Engel proposes that the portraits produced in this moment straddled an allegiance to both imperial and local rule.

In Chapter one, Engel highlights the beginnings of this pictorial tradition in Lima in the sixteenth century as sitters negotiated their new colonial position in relation to Spanish officials. Grounding her study in the visual, Engel also looks to inventory records, treatises, and illustrated chronicles, including Felipe Guamán Poma’s El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno (1615-1616), to position Lima as a culturally thriving capital whose local artists and authors offered an alternative to the imperial history written and visualized by Spaniards. Engel suggests that Guamán Poma’s inclusion of Incas and Coyas alongside viceroys in the chronicle evidences his desire to guarantee their place in colonial history. He was highly critical of the Spanish colonial social order, whose imperial agents worked “to buttress the emerging viceregal hierarchy” (25).

Chapter two looks at the earliest portraits of Spanish monarchs that make up a significant portion of the South American collections. Because Spanish royalty never ruled their American territories directly, relying on appointed and local proxies to govern in their stead, their portraits had to serve as an effective visual alternative to their physical absence. Chapters three and four explore specific portraits of viceroys and the portrait series from the three capitals. In Chapter five, Engel examines the appropriation of the pictorial elements of viceregal portraiture to images of early republican leaders to fashion their political authority during the independence period.

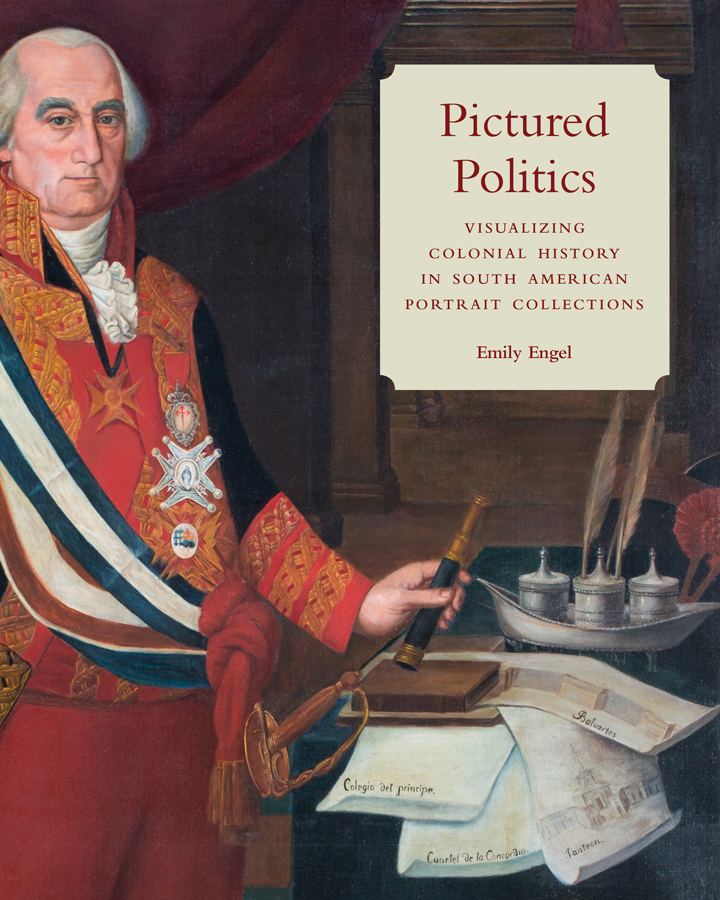

In her evaluation of specific paintings, such as Cristóbal de Aguilar’s portrait of the Viceroy José Antonio de Mendoza Caamaño y Sotomayor (Fig. 1), Engel describes the sitters’ occupation of pictorial space as well as their bodies, clothing, and accessories. Aguilar specialized in portraits of prominent figures of Limeñan society, including viceroys, who are, according to Engel, individuated through dress and facial features. The artist employed the traditional format of full-length figures set within an interior that included accessories relevant to the sitter, the artist’s signature, and heraldic imagery. Viceroy Mendoza’s ensemble displays a dominant pattern of swirling, stylized botanicals that have presumably been produced by embroidery, a common means for rendering such designs in eighteenth-century men’s garments.

Although Engel mentions that dress was important and notes certain sartorial shifts, she does not offer particulars about specific garments, fashions, textiles, or dyes. As she states, the colonies were often forced to depend on Spain for many of its goods, including textiles, but she does not explain how and where the uniforms, men’s coats, and other items were manufactured, nor does she offer any details about the designs, patterns, or styles featured. Considering the fact that Engel underscores dress as a marker of status in these portraits, it is surprising that she does not address questions that arise about the production of the clothing worn by the viceroys and others. Were Spanish fashions, including the standard black Habsburg court attire that carried over into the early Bourbon years, simply translated into a colonial context? If so, how? Were they directly copied from Spanish portraits? Were the garments produced in Spain and shipped to the colonies? Did viceroys add local elements to differentiate themselves from other viceroyalties? Also, how were military uniforms made, especially those produced during the independence period?

Engel’s sections devoted to official Limeñan portraits and their role in forging a collective colonial history emerge as her strongest. Chapter four, which treats viceregal portraits in Bogotá and Buenos Aires, is the least cohesive part, combining many disparate subjects and ideas. The comparisons, however, among the pictorial traditions of Lima, Bogotá, and Buenos Aires are helpful in considering the circumstances unique to each locale. As Engel posits, despite the formulaic quality of these portraits and the value of their adherence to stylistic tradition, they changed over time, responding to variable conditions. Thus, she proposes these images were not static but in constant negotiation. Engel treats each of the viceregal capitals as a distinct site with its own political and cultural history; that is, she does not uniformly interpret the portraits. Rather, she seeks to understand the different political circumstances in which and diverse constituencies for whom these images were created.

Overall Engel’s book is a welcome addition to the scholarly dialogue about portraiture, one that brings the complexities of colonial relationships to bear on the discussion of a genre viewed as embodying power. Pictured Politics will appeal to specialists and students of colonial art and portraiture studies. Most of the images she analyzes have never been reproduced in an English language art history text. Their appearance within Engel’s book widens our understanding of portraits produced in the eighteenth century and the ways in which they were employed and displayed in a colonial context. Engel treats this understudied material in richly nuanced ways with compelling discussion.

Tara Zanardi is Associate Professor of Art History at Hunter College CUNY, NY

[1] For example, see Maria H. Loh, Still Lives: Death, Desire, and the Portrait of the Old Master (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015); Xavier Bray, with Manuela Mena Marqués and Thomas Gayford, Goya: The Portraits (London: The National Gallery, 2015); and Emma Dexter and Tanya Barson, Frida Kahlo (London: Tate Modern, 2005).

[2] See Heather McPherson, Art and Celebrity in the Age of Reynolds and Siddons (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017); Malcolm Baker, The Marble Index: Roubiliac and Sculptural Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Britain (London: The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2015); Jennifer G. Germann, Picturing Marie Leszczinska (1703–1768): Representing Queenship in Eighteenth-Century France (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015); Amy Freund, Portraiture and Politics in Revolutionary France (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014); and Magali Carrera, Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Painting (Austin: University of Texas, 2002).

[3] Natalia Majluf, “Fashioning a Nation: Military Dress in Peruvian Independence, 1821-1822,” in Tara Zanardi and Lynda Klich, eds., Visual Typologies from the Early Modern to the Contemporary: Local Practices and Global Contexts (New York: Routledge, 2018), 185-199. See also Ilona Katzew et al., Contested Visions in the Spanish Colonial World (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2011).

[4] See Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004); and Carrera, Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body.

Cite this note as: Tara Zanardi, “Pictured Politics: A Review,” Journal18 (November 2020), https://www.journal18.org/5414.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.