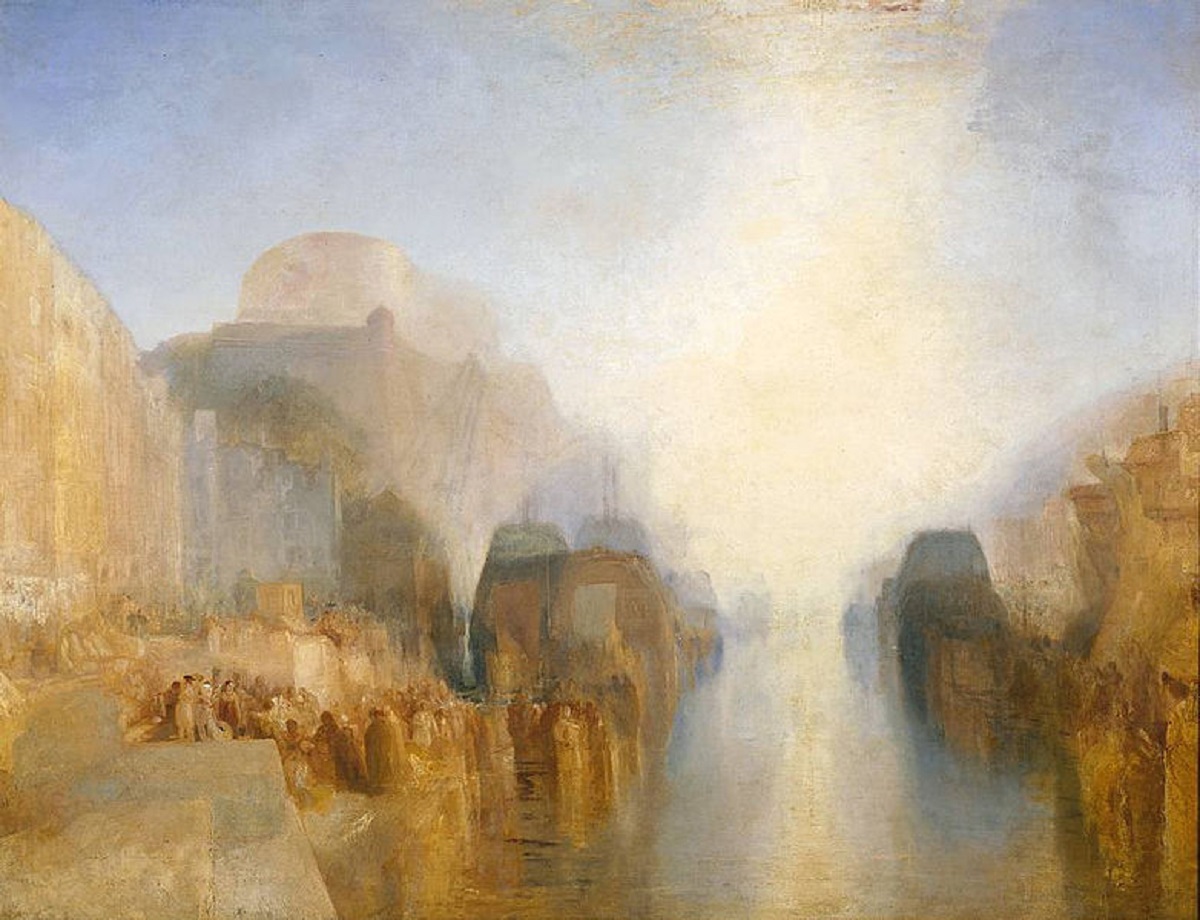

Fig. 1. Installation view of Turner’s Ancient and Modern Ports, The Frick Collection, Oval Room. Photo: Michael Bodycomb.

J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) is now, indisputably, a titan in the United States of America. A series of exhibitions in major institutions has catapulted him to the heights where he belongs in the canon—the greatest British Artist, the greatest painter of the first half of the nineteenth century, the greatest landscape painter ever, and with a reputation on a Raphael/Titian/Velazquez/Picasso/Matisse level. This is good. And deserved. And while the National Gallery in Washington, D.C./Dallas Museum of Art/Metropolitan Museum of Art’s retrospective of around 150 works from 2007-2008 may be the final comprehensive display of his art on these shores, since that time there has been, among others, the more focused “Turner and the Sea” (Peabody Essex Museum, 2014), “Sublime: The Prints of J.M.W. Turner and Thomas Moran” (New York Public Library, 2014-15), “J.M.W. Turner: Painting Set Free” (Getty Center and de Young Museum, 2015), “Turner’s Whaling Pictures” (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016),[1] and the room of his paintings that formed a highlight of the Met Breuer’s “Unfinished” (2016). Many of these were made possible by Tate Britain’s generosity in sharing its collection far and wide, as is the present display. There are great Turners across America, especially in Boston and Cincinnati and Williamstown, and in numbers at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven and at the Frick Collection in New York. The latter institution is unrivaled for producing scrupulously researched and beautifully presented exhibits about works in its collection, and at last the grand Turners that have lived in Henry Clay Frick’s West Gallery since being installed there in 1942, Dieppe and Cologne, both purchased by the man himself and thus not able to be lent, have been granted their own showcase (Fig. 1).

The Frick’s Dieppe was featured in a production still for Mike Leigh’s memorable biopic Mr. Turner (2014), the finest cinematic effort in that genre and another example of the international rise in the artist’s reputation. An early scene in the film finds Turner (Timothy Spall) returning home from European travels and catching up with his father (Paul Jesson) in a most economical manner:

TURNER SENIOR: How was your crossing?

TURNER: Set fair on departure, lumpy in the middle.

TURNER SNR: Did you sail from Rotterdam?

TURNER: No, Dieppe …

TURNER SNR: Were your travels productive?

TURNER: Exceeding refreshing, old Daddy. Amsterdam: had a gander at the Rembrandt; Militia Company, Antwerp Cathedral; Rubens, the triptych; Flanders: still as flat as a witch’s tit.

TURNER SNR: … Did you find tolerable diggings?

TURNER: Stinking fleapit at Dieppe, then moved to the harbour. Westerly aspect, fine sunset. Oh, Daddy, I’m in need of an eight by six.

TURNER SNR: I have a seven by five and a half ready sized and primed.

TURNER: That should suit.

TURNER SNR: Right you be.[2]

That is the extent of his travelogue, concluding with Turner requesting a canvas—preferring to preserve his experience of Dieppe in paint than through speech or pen. It is appropriate that the film, and this exhibition, begins in the early 1820s and Turner’s productive travels of those years, for the resulting pictures signaled a shift in his art, as the show’s organizers write, a movement “away from his earlier naturalism to a more imaginative treatment of light and color.”[3] This is brilliantly on display at the Frick, and the artist’s spare descriptions in Leigh’s screenplay reflect his growing interest in the general over the detailed and specific in a remarkable evolution of vision.

The Frick display is spread over two rooms and includes seven oils, two sketchbooks from Tate, three engravings, and twenty-six watercolors, all from at least eighteen different public and private collections. Along with three four-foot historical pictures, the stately Oval Room is dominated by the Frick’s aforementioned Harbor of Dieppe: Changement de Domicile (exhibited 1825) and Cologne, the Arrival of a Packet-Boat: Evening (1826), which now flank a remarkable oil on the same large scale (nearly 6 x 7 1/2 feet) from Tate, The Harbor of Brest: The Quayside and Château (ca. 1826-28). They form a triptych of major works. John Broadhurst owned the first two, and Turner intended Brest to land at his feet as well, but he instead chose to sell his collection. Consequently, Turner never finished Brest, and it was left to the nation after the artist’s death in 1851. Nearly a century later, it was rediscovered by none other than the director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, who found it rolled up in basement storage at Millbank in 1943, cleaned it with a mop, and deemed it an aborted masterpiece.[4] He was correct. Nearby are the two diminutive sketchbooks, one of the Rhine from 1817 featuring a drawing of Cologne, and one dated to 1824 of the River Meuse and Moselle with drawings of Dieppe. The inclusion of these sketchbooks is welcome, but precludes allowing natural overhead light into the Oval Room. The result is that on bright days one looks longingly at the adjacent West Gallery wherein the Frick pictures usually hang, flooded by sunlight, and can only wonder at how Brest would look if so boldly illuminated.

Fig. 2. J. M. W. Turner, The Harbor of Brest: The Quayside and Château (ca. 1826-28). Tate Britain, London. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Harbor of Brest: The Quayside and Château is a remarkable picture, and dominates the display from its central position (Fig. 2). Turner’s late works of the 1840s, some unfinished, some painted as if made of mother-of-pearl, are very familiar by this point, if not seen as his greatest productions. In its nascent state, Brest shares their suggestiveness, their coloristic radicalism, their atmospheric drama. The view of this harbor in Brittany is dominated by massive forms blocked out in delicate shades including the bulk of the ancient Château de Brest in the upper left. Pillowy cloudbanks rise above. The painting is organized by orthogonals receding towards some indistinct vanishing zone in the deep distance at right. Ironically, this central, brightest zone is the most finished, its watery reflections bearing the only instance of impasto used in the painting, while the edges of the picture remain but thinly blocked out. Tate conservator Rebecca Hellen’s enlightening essay in the catalogue reveals much that is new about Turner’s technique at this stage in his career, and all six of the oils in the Oval Room show his novel approach: a kind of reverse peripheral vision whereby the sun and light filled centers are absent of form, and the edges are more fully realized and carefully drawn.[5] This is not how we see, but it is how Turner wants us to see. The layout and organization of masses and perspective in this incomplete and unexhibited work would not go to waste – Turner replicated them almost exactly one year later in 1829 for his magisterial Ulysses deriding Polyphemus—Homer’s Odyssey (National Gallery, London). But Brest is 30% larger than that mythological scene, and even though it is the same scale as Dieppe and Cologne, it seems more monumental than its completed Frick cousins. Most remarkable are the vertical reflections of buildings and ships and people in Breton costume in the foreground water, and the extraordinary delicacy of the megilp (oil and resin) glazes, its “molten colors” as curator Susan Grace Galassi has described them. Brest‘s luminosity, as with that of Regulus (1828, Tate) hanging across the room, is blinding, and forms a predecessor to similar attempts to produce pictures that appear to emit light, from the work of Valdemar Schønheyder Møller (1864-1905) to that of the contemporary painter Stephen Hannock (b. 1951). This is partly down to Turner’s technique and partly the adoption of technologically advanced and newly introduced high-keyed colors. Ultimately, the still-born Brest has the quality of a fresco—chalky and with great masses of monumentally-scaled forms. It is a picture that may not have a finished narrative from ancient or modern history, but which nonetheless feels deeply historical, moving, and impressively if inadvertently abstract.

Fig. 3: Installation view of Turner’s Ancient and Modern Ports, The Frick Collection, East Gallery. Photo: Michael Bodycomb.

The low light levels found in the Oval Room are also in effect next door in the East Gallery, but the watercolors and prints, arrayed against deep red walls and panels, are perfectly spotlit and glowing (Fig. 3). They are arranged by region (France, Germany, England) and accompanied by a useful map showing where the artist traveled. Turner is good at everything, this is clear, and there are watercolors here that both amaze and successfully continue the strong theme of the exhibition—ports as places of passage, history, and templates for aesthetic experimentation. Highlights include Grenoble Bridge (ca. 1824) from Baltimore, the kind of topographically concise and coloristically intricate picture that drove John Ruskin to pleasant paroxysms (he described it as “exquisitely realized,” and as usual he was right).[6] Also, the early Cologne from the River (1820) from the Seattle Art Museum is remarkable in its translucency of water and sky. The Fogg Museum’s Devonport and Dockyard, Devonshire (ca. 1825-29) is awesome in its sweep of weathery sky above—in an inversion of the storm in Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps (1812, Tate)—while pacifically celebrating the industry that won the Napoleonic Wars below. The exquisite Sun-Rise: Whiting Fishing at Margate (1822) is an epically placid view of the port in eastern England that meant much to Turner, and panoramic despite its two-foot width. Fish-Market, Hastings (Early Morning) of 1824 is somehow both detailed and diaphanous, and beautifully colored throughout.

The catalogue propels the exhibition’s argument well, though the plentiful plates are a bit drained of color. Not so for Gillian Forrester’s enriching introductory essay, “Modern Histories,” which positions Turner in the currents of European history and illuminates his social context, empathies, and responsiveness to political and cultural change. It should be required reading on the artist. Ian Warrell and Galassi deliver, respectively, a useful discussion of Turner’s works in the 1820s and a detailed examination of Dieppe and Cologne. And Joanna Sheers Seidenstein deals with Turner’s images of ports from ancient history, and how they reflected upon life in his present. There is a useful appendix on Turner’s patron Broadhurst.

Turner, who as Forrester notes was always more circumspect than celebratory when it came to images of empire, is the type of artist whose works remain inherently topical in political terms. The exhibit at the Met in the summer of 2008 followed on the heels of a large but tepid Gustave Courbet retrospective in the exact same galleries, and cast the British artist’s more complicated radicalism into sharp relief in a contentious election year.[7] Turner’s curiosity about Europe and its continuously negotiated borders, heritage, peoples and their occupations, natural scenery, flora and fauna, and his wariness towards unchecked nationalism, represent an openness and tolerance unfortunately lacking in the present era of Brexit/Trump/Putin/Le Pen etc. The symbolic freedom of ports, locales of arrival and embarkation of people and goods, and their consequent implications of liberty of movement and picturesque chaos, appealed to this enlightened son of a barber, an “exceeding refreshing” pleasure in life and history he vividly conveyed in paint.

Jason Rosenfeld, Ph.D., is Distinguished Chair and Professor of Art History at Marymount Manhattan College and a critic at The Brooklyn Rail

[1] The Brooklyn Rail, July 11, 2016.

[2] Mike Leigh, Mr. Turner, Sony Classics, 6-7.

[3] Susan Grace Galassi, Ian Warrell, and Joanna Sheers Seidenstein, “Preface and Acknowledgments,” Turner’s Modern and Ancient Ports: Passages through Time, (New York & New Haven: The Frick Collection and Yale University Press, 2017), viii.

[4] Rebecca Hellen, “‘Unfinished Productions’: History and Progress in Turner’s 1820s Port Scenes of Dieppe, Cologne, and Brest,” 113.

[5] Hellen, “‘Unfinished Productions,’” 111-119.

[6] David Blayney Brown entry on Grenoble Bridge, c. 1824, Tate: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/joseph-mallord-william-turner-grenoble-bridge-r1146532

[7] See my review with an overview of critical reception of these shows: “Victorians Live: Turner in America,” Victorian Literature and Culture 38:1 (March 2010), 293-300.

Cite this note as: Jason Rosenfeld, “Passages through Time: Turner’s Modern and Ancient Ports”, Journal18 (April 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1728

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.