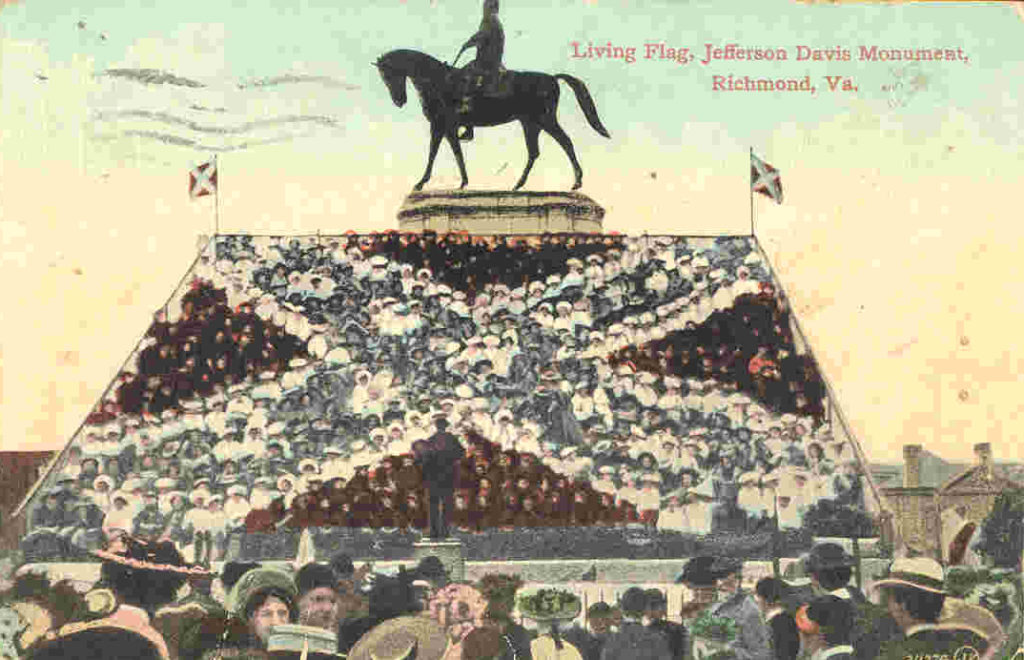

Confronted with mass Black Lives Matter protests locally and internationally, Virginia governor Ralph Northam announced in early June 2020 that the state would remove the statue of Robert E. Lee on Richmond’s Monument Avenue, a late nineteenth-century real-estate scheme built around a series of memorials to Confederate heroes (Fig. 1). At the same time, the city’s mayor announced that it would remove the other effigies, too.[1]

For thirty years, beginning with the removal of statues of communist leaders after 1989, continuing with the efforts to topple Confederate monuments in the U.S. South, energized by revulsion at the killings in Charleston and Charlottesville, and reaching a new intensity during the demonstrations following the murder of George Floyd, critical evaluation of the landscapes of commemoration has ranged from heated public debate to official removal to outright destruction by citizens. All parties recognize the global nature of what archaeologist Dan Hicks calls “Fallism.” In requesting the removal of a statue of journalist Indro Montanelli in Milan, for example, the civil-rights group I Sentinelli cited the protests over George Floyd’s killing and the fall of the statue of English slaver Edward Colston as their inspiration.[2] In the same mood, one of I Sentinelli’s critics equated their demand for the removal of Montanelli’s memorial to the graffiti tagging of Winston Churchill’s statue in London.[3]

Stories such as these are played out globally with increasing frequency, the terms of engagement similar everywhere. Usually some of those who condemn the honorees’ actions characterize the monuments’ removal as the erasure of history or art. It is not surprising, therefore, that historic preservation is often evoked as a reason for the monuments’ retention and its laws used to thwart changes in the civic landscape. In New Orleans in the 1990s, conflict over the proposed removal of an obelisk commemorating a white-supremacist uprising against the mixed-race Reconstruction government of the state was complicated by the intervention of the state historic preservation officer, who professed not to see anything about the monument that promoted racial hostility. The obelisk stood until the city’s mayor finally removed it in spring of 2017, along with other Confederate memorials in the city. In Salisbury, North Carolina, opponents of a memorial to be built on an erased African-American cemetery invoked historic preservation concerns over the removal of a few stones in a wall that separated it from an adjacent white cemetery, a wall that had been erected explicitly to divide an originally mixed-race cemetery.[4] In Alabama, Birmingham’s attempt to remove a Confederate obelisk was blocked by a state law protecting such works. Violations incur a $25,000 fine to be paid to the state’s historic preservation fund. Again, it was finally removed at the mayor’s insistence after the George Floyd murder, but the state’s attorney general has vowed to prosecute him for doing it. Most recently, in Richmond, Virginia, a state-court judge enjoined the removal of the Robert E. Lee monument. Those who sued to prevent Lee’s fall included the Monument Avenue Preservation Group, which seeks “to preserve, protect, maintain and celebrate the Civil War commemorative monuments on Richmond’s Monument Avenue,” according to its Facebook page. They claimed that when the state accepted the statue in 1890, it had agreed to “perpetually care for and protect” it. Following a time-honored practice, protestors had decorated Lee, and the plaintiffs cited it as a dereliction of the state’s negligence in allowing that to happen (Figs. 2 and 3).[5] On June 18, the same judge extended the injunction, saying that the monument belonged to “the people,” and that the governor was merely its custodian. On the same day, the Monument Avenue Preservation Society (a rival of the Preservation Group) announced its support for removal. “For too long, we have overlooked the inherent racism of these monuments, and for too long we have allowed the grandeur of the architecture to blind us to the insult of glorifying men for their roles in fighting to perpetuate the inhumanity of slavery,” the board of directors wrote.[6]

In short, historic preservation enters many conflicts over monuments, either as a delaying tactic or from a sincere, if misguided, belief that monuments are themselves “history” and that their fall is a kind of 1984-esque rewriting of the past. These tactics are enabled in part by many states’ practice of including all monuments of a particular kind—in this instance, Confederate statues—as a bundle in “multiple resource nominations” that eliminate the need for individual analysis or evaluation of the memorials’ collective import, thus throwing over the status quo a cloak of ostensibly impartial “history.” Indeed, the Richmond judge wrote that “the public interest weighs in favor of maintaining the status quo.”[7]

Arguments about abstractions such as history and art deflect attention from the specificity of the objects themselves. Why were they made? Why then? Why there? Why should we retain them (or not)? To date, these questions tend to be subsumed under the character assessment of individual historical people. Take the ongoing conflict over Indro Montanelli’s statue, mentioned above.

Montanelli is revered by many Italians for his (belated and ambivalent) opposition to Italian fascism during its last years. Initially an ardent supporter, Montanelli gradually became disillusioned with the regime’s behavior and in the latter days of World War II joined the partisans. In 1936, though, Montanelli had written in the periodical Civiltà Fascista of Italians’ “fatal superiority,” and he joined the army to take part in the conquest of Abyssinia (Ethiopia), where he led a detachment of 100 Ascari (Eritrean soldiers). In Africa Montanelli purchased, for 500 lire, a horse, a rifle, and a twelve-year-old girl, Destà, who became his servant and compagna d’alcova, or bed partner. While some accounts, even critical ones, refer to his having married Destà, the arrangement was one known as madamata in Italian East Africa: Destà was “less than a wife and a little more [like] a slave,” as one journalist put it.[8] Indeed, when Montanelli left East Africa, he claimed he gave Destà to General Pirzio Biroli, a man who maintained a harem.[9]

Throughout the remainder of his life, Montanelli defended his actions unashamedly, dismissing questions about the girl’s age as a matter of “cultural differences.” He described Destà in a 1982 interview as a “docile little animal” whom he housed in a tucul (circular hut) with some chickens. “I chose well; she was a beautiful girl … twelve years old.”[10] Criticism of his actions persisted for decades, and Montanelli claimed a year before his death that Destà had actually been fourteen, the minimum age for marriage in Italy in 1936. He had visited her in the 1950s, he said, at which time she greeted him as a father. She had even named one of her children Indro.[11]

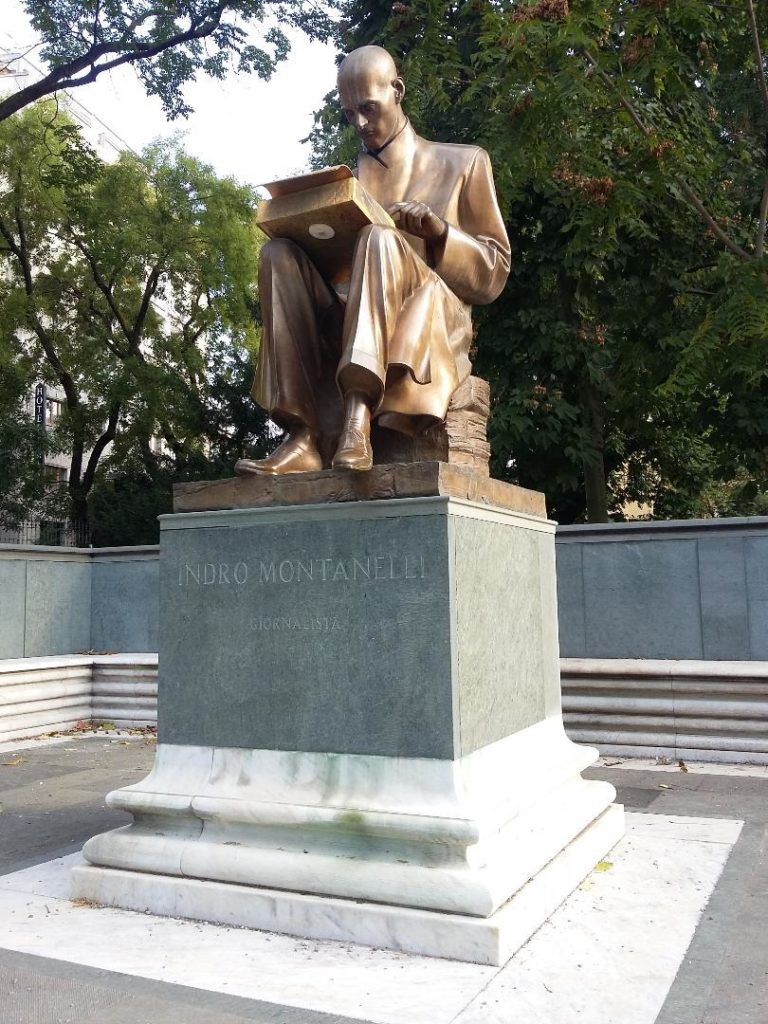

In 2006 the city of Milan honored Montanelli with a statue erected in the newly christened Giardini Pubblici Indro Montanelli (Fig. 4). The feminist group Non una di Meno doused it with pink paint on March 8, 2019. The following June brought I Sentinelli’s demands for its removal. Three days later the Milan Students’ Network and LuMe (Laboratorio Universitario Metropolitano) gave it another redecoration, this time with red paint. They spray-painted razzista and stupratore (racist and rapist) on the base. City authorities power-washed the paint away and shrouded Montanelli in plastic. The city’s Minister of Culture compared the students to Fascist squadristi and described their actions as “illiterate radical chic under the color of fighting racism.”[12]

Montanelli was one of those men whose monuments are most likely to attract adverse attention. Indeed, his public and private lives were remarkably similar to those of Thomas Jefferson and Mohandas Gandhi, whose monuments are also coming under fire. All three (and many others) are revered as advocates of freedom and human rights, while their personal actions fell far short of their professed ideals. Their partisans claim that their positive ideas overbalance their negative characters. In Montanelli’s case, his career as a journalist who defended the “liberty of the state” outweighed a “single episode in his young life,” even if one considered it “a grave error, impardonable.”[13] One passerby told a journalist that Montanelli was “a great man. … It is absurd to be against the people who built the history of Italy and history in general.” To another passerby, he was “absolutely not racist, but simply of his time.”[14] Even Milan’s center-left mayor Giuseppe Sala admitted that he had been taken aback by Montanelli’s casual admissions of his actions in Ethiopia (they are widely available on video). Nevertheless, his was “an extraordinary pen” whose “qualities are indisputable.” “Lives must be judged in their complexity,” Sala concluded, so the statue would remain.[15]

Filippo Barberis, head of Milan’s center-left party and a supporter of the monument, made a point worth considering. Views such as those of I Sentinelli represented the “moralization of history and memory,” which was a form of censorship that he found “wrong and dangerous.”[16] In fact, the discussion of controversial monuments does often resemble the weighing of souls at the Last Judgment.

But to debate the appropriateness of individual statues on the basis of their subjects’ character is a losing proposition. The moral arguments against individual memorials—that Confederate monuments are celebrations of white supremacy, that Montanelli was a racist, a pederast and a slaveholder, that Edward Colston was a slave trader—have been made repeatedly and have usually been acknowledged by their defenders. There is no point in continuing to stress them, because in all cases great goods and great evils coexist incommensurately and no final accounting convincing to everyone can be made. Does the Declaration of Independence outweigh Jefferson’s slaveholding and his treatment of Sally Hemings? Do Winston Churchill’s actions during the Anglo-Boer War outweigh his leadership during World War II? Does Colston’s funding of many of Bristol’s most cherished cultural institutions excuse his doing so with money obtained by trading human beings? It is easy for defenders to say “yes, I know, but.” “Yes, I know he did bad things, but.”

Character assessment is a dead end that sometimes prompts Fallists to suggest replacing an objectionable figure with a more acceptable one—in Montanelli’s case, with a memorial to the poet, critic, and translator of American literature Fernanda Pivano, who will eventually turn out to have her own unsettling faults. Character assessment dissipates vital energies that can better be directed otherwise.

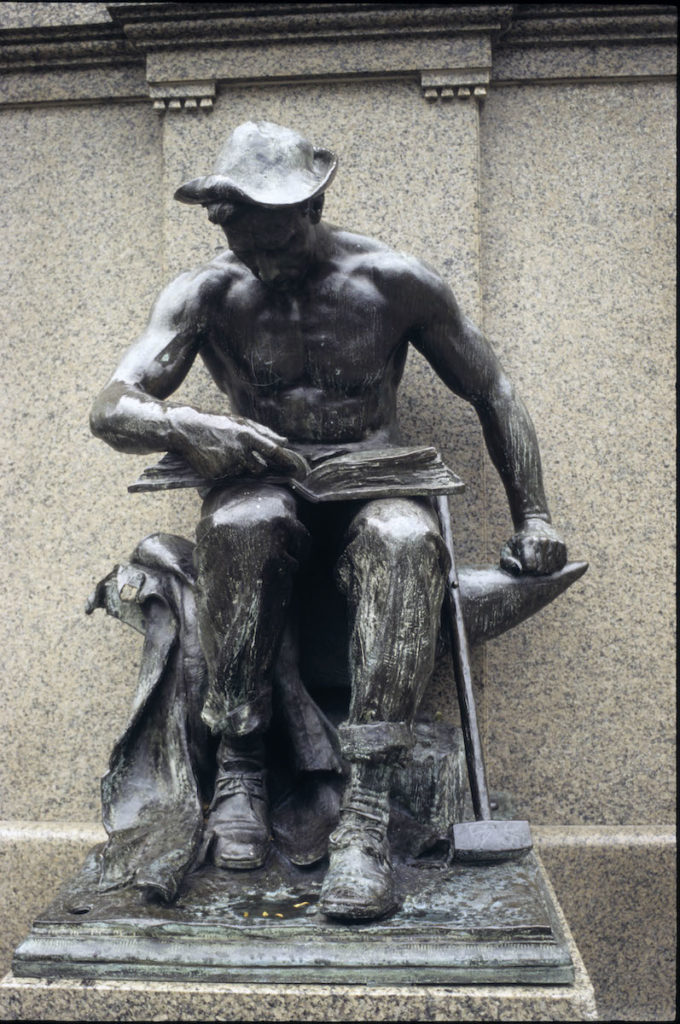

That is, it is time for Fallists to develop a new critical strategy, one that would focus on the entire body of civic memorials. Monuments are components of expansive landscapes that, as a group, tell stories and narrate origin myths. They tend to be erected in flurries during times of extreme unrest. For example, the United States between the Civil War and World War I was a time when the economy was becoming industrialized and corporatized and the work force proletarianized. It was a time when increasing numbers of people were opting for the city over the countryside. It was a time when millions of newly freed African-Americans were seeking to build new lives, when enormous numbers of immigrants, many non-white, were landing in American ports, and when the government and the non-native citizenry were doing their best to exterminate the Indigenous population. It was a time when the United States entered into frankly imperialist adventures in the Caribbean and the Pacific Islands. During that time, large numbers of monuments were erected that celebrated individualistic economic enterprise, boot-strap social advancement, agrarian values, and westward expansion (Figs. 5 and 6).[17] Non-white Americans appear only in monuments as whites’ enablers or as enemies to be defeated (Figs. 7 and 8). In a time of great change, that is, monuments sought to reassert an older story of white American individualism. The Confederate monuments were a subset of this Victorian memorial landscape. This context can only be understood by viewing all the monuments as a single assemblage.

There is a more subtle way in which monumental landscapes work. They are the ubiquitous setting of our everyday lives. Monuments, in their carefully chosen settings, mutually reinforce one another and purport by their simple presence to define our civic DNA. They are key tools in the creation of what Antonio Gramsci called hegemony, the process by which people accept the legitimacy of the current order without the necessity of (much) violent enforcement. For Gramsci, a revolutionary, hegemony would be achieved when revolutionary leaders shaped “a new ideological soil” and “a reform of consciousness and the methods of knowledge.”[18] One might argue that, for many Americans, the monumental landscape of the late nineteenth century succeeded in doing just that. Some Southerners, for example, still accept at face value the white supremacist claims of the builders of Confederate monuments without necessarily understanding them as such. These figures—Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis, as well as later white supremacist politicians such as “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman and Strom Thurmond—stand as honorable members of our civic pantheon. But as a technique of legitimacy, hegemony needn’t mean that we embrace the monumental so wholeheartedly. We might object to some or even many aspects of it. We may even reject it wholesale, but not enough to do anything about it. We grant it a grudging acceptance as a fact of life: that’s just the way things are. And the presence of these monuments in the everyday landscape, even if we don’t pay particular attention to them, facilitates this acceptance. A succinct definition of a successful ideology might be that it convinces people that a particular interpretation of society is actually a natural and unalterable phenomenon.

Thinking of the memorial landscape as a totality brings us to a second, much more important point that Barberis made. On the surface, it appears to be a version of the common “slippery slope” lament: “but if they can get rid of Robert E. Lee, won’t they want to get rid of George Washington next?”[19] This way of putting it is a version of the moral assessment of individuals. But Barberis put it a little differently: “If this is the criterion for removing statues or changing street names we would have to reconsider (or reevaluate) 50 percent of the world’s place names.”[20] A a resident of Bristol agreed in his comments about the Colston statue: “If you pull down every statue around the world that has anything to do with slavery, abusing people, or war, there would be nothing left,” said Nick Morris. “You might as well pull down the pyramids.”[21]

This is not a fear that individual heroes will be lost. It acknowledges that the entire story is being challenged, and may be radically recast or jettisoned entirely, because that story is an inextricable mix of good and evil. Montanelli’s actions as a slaver and pederast were not simply youthful errors, but clues to his lifelong conception of “liberty” and who could properly claim it. Edward Colston’s trading in African bodies was inseparable, morally and philosophically, from his benefactions to white Bristolites. Jefferson’s freedom to think high thoughts about human liberty and his ability to make his way in politics were inseparable from the wealth and labor provided by enslaved people.

And so we return to historic preservation as a tool of political ideology. The Richmond judge declared that Lee belonged to “the people.” Who are those people and why do they want to keep Lee? Another Virginia judge forbade the removal of a Lee statue in Charlottesville and ordered the city to remove a shroud that then covered it because it “obstructed rights of the public … to be able to view the statues.”[22] It is important that monuments remain intact on their intended sites, or the story would fall apart. This was perhaps clearest in the Alabama law that protects Confederate monuments. Not only can they not be removed, they can’t be moved, renamed, added to, subtracted from or obscured. The conservative and even the liberal judges who block the removal of Confederate monuments understand on one level that the issue is about more than a single chunk of stone or bronze, but about an entire civic mythology.

Dell Upton is Distinguished

Research Professor of Architectural History at UCLA, Los Angeles CA

[1] Bill Chappell, “Massive Robert E. Lee Statue in Richmond, Va., Will Be Removed,” NPR, June 4, 2020, www.npr.org/2020/06/04/869519175/massive-robert-e-lee-statue-in-richmond-va-will-be-removed (accessed June 9, 2020). Lee’s statue belongs to the state, while the city owns the other Monument Avenue statues.

[2] Dan Hicks, “Why Colston Had to Fall,” Art Review, June 9, 2020, www.artreview.com/why-colston-had-to-fall (accessed June 15, 2020); “Lettera appello al sindaco e al consiglio comunale di Milano,” posted on i Sentinelli’s Facebook page, June 10, 2020 (accessed June 16, 2020).

[3] Maurizio Giannattasio, “I Sentinelli di Milano: ‘Via la statua di Montanelli dai Giardini’. Tanto no, dal Pd a centrodestra,” Milano/Cronaca, June 10, 2020, https://milano.corriere.it/notizie/cronaca/20_giugno_10/i-sentinelli-milano-via-statua-montanelli-giardini-fu-razzista-9fcf1f30-ab36-11ea-ab2d-35b3b77b559f.shtml (accessed June 15, 2020).

[4] Dell Upton, What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 50-64, 202-204.

[5] Staff and Wire Reports, “Richmond judge bars removal of Lee statue on Monument Avenue for 10 days,” June 8, 2020,” https://www.richmond.com/news/local/update-richmond-judge-bars-removal-of-lee-statue-on-monument-avenue-for-10-days/article_82e76fb6-58f0-5b65-8a8b-4435a73b8775.html (accessed June 9, 2020); Sarah Rankin, “Judge Blocks Virginia Governor From Removing Robert E. Lee Statue for 10 Days,” Time, June 9, 2020, https://time.com/5850456/judge-blocks-removal-robert-e-lee-statue (accessed June 9, 2020).

[6] Justin Mattingly, “Richmond judge extends injunction barring removal of Lee statue on Monument Avenue,” June 18, 2020, https://www.richmond.com/news/virginia/updated-richmond-judge-extends-injunction-barring-removal-of-lee-statue-on-monument-avenue/article-2494d3df-fcf5-5c5d-b66e-5fe3c01e9481.htm (accessed June 9, 2020).

[7] Staff and Wire Reports, “Richmond judge bars removal of Lee statue.”

[8] Annalisa Teggi, “‘Lei, signor Montanelli, violentò una bambina di 12 anni?’ chiese Elvira Banotti, Aleteia, August 16, 2018: https://it.aleteia.org/2018/08/16/indro-montanelli-elvira-banotti-violenza-bimba-12-anni-africa/(accessed June 15, 2020); Laura Fano, “I ‘giochi proibiti’ del giovane Montanelli in Africa,” Il Sud Est, http://www.ilsudest.it/sociale-menu/78-sociale/6402-i-qgiochi-proibitiq-del-giovane-montanelli-in-africa.html (accessed June 15, 2020).

[9] Igiaba Scego, “Not One Less,” World Literature Today Newsletter, Autumn 2019, https://www.worldliteraturetoday.org/2019/autumn/not-one-less-igiaba-scego (accessed June 18, 2020).

[10] Fano, “I ‘giochi proibidi.”

[11] The Associated Press, “Legacy of Late Italian Journalist Stained by Colonial Past,” New York Times, June 14, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2020/06/14/world/europe/ap-eu-italy-journalist-statue-defaced.html (accessed June 16, 2020). To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever attempted to verify these claims about his later meeting with Destà. In recent days, researchers have questioned whether Destà ever existed. Nevertheless, it was a story Montanelli acknowledged and embellished, and that reveals his moral values as a colonizer. Davide Fiammenghi, “La sposa-bambina di Montanelli è veramente esistita?,” June 18, 2020, https://www.stradeonline.it/diritto-e-liberta/4244-la-sposa-bambina-di-montanelli-e-veramente-esistita (accessed June 19, 2020).

[12] Riccardo Liberatore, “Statua di Montanelli a Milano, a imbrattarla un colletivo di studenti. Aperta un’inchiesta,” Open, June 14, 2020, https://www.open.online/2020/06/14/ripulita-statua-montanelli-sentinelli-peggio-vernice-ossa-chi-butta-caciara/ (accessed June 15, 2020).

[13] “Legacy of Late Italian Journalist;” “Statua da rimuovere, la Fondazione Montanelli: ‘Richiesta strumentale e inaccettabile,” Il Giorno Milano, June 11, 2020, https://www.ilgiorno.it/milano/cronaca/statua-montanelli-1.5219737 (accessed June 15, 2020); Maurizio Giannattasio, “I Sentinelli di Milano: ‘Via la statua di Montanelli dai Giardini.’

[14] AFP News Agency, “Statue of famous Italian journalist defaced in Milan,” al-Jazeera, www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/statue-famous-italian-journalist-defaced-milan-200614183625275.html (accessed June 15, 2020).

[15] Alessandra Corica, “Montanelli e la statua della discordia: a Milano flash mob di Forza Italia e contro manifestazione di ‘Non una di meno,’” La Repubblica, June 15, 2020, https://milano.repubblica.it/cronaca/2020/06/15/news/indro_montanelli_statua_razzismo_milano_proteste-259249683/ (accessed June 15, 2020); “Milan: Montanelli statue defaced with red paint,” Wanted in Milan, June 14, 2020, https://www.wantedinmilan.com/news/milan-montanelli-statue-defaced-with-red-paint.html (accessed June 14, 2020).

[16] Maurizio Giannattasio, “I Sentinelli di Milano: ‘Via la statua di Montanelli dai Giardini.’”

[17] Dell Upton, “Why Do Today’s Monuments Talk So Much?,” in Commemoration in America: Essays on Monuments, Memorialization and Memory, ed. David Gobel and Daves Rossell (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 119-120.

[18] Gramsci, quoted in James Joll, Antonio Gramsci (New York: Penguin, 1977), 128.

[19] Dell Upton, “Bully Pulpit: The #HimToo Movement,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1634.

[20] Maurizio Giannattasio, “I Sentinelli di Milano: ‘Via la statua di Montanelli dai Giardini.’” Thanks to Joseph Sciorra for helping me translate this passage.

[21] Mark Landler, “In an English City, an Early Benefactor Is Now ‘a Toxic Brand,’” New York Times, June 14, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/14/world/europe/Bristol-Colston-statue-slavery.html (accessed June 16, 2020).

[22] Amy Held, “Shrouds Pulled from Charlottesville Confederate Statues, Following Ruling,” NPR, February 28, 2018, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/02/28/589451855/shrouds-pulled-from-charlottesville-confederate-statues-following-ruling (accessed June 9, 2020).

Cite this note as: Dell Upton, “Monuments and Crimes,” Journal18 (June 2020), https://www.journal18.org/5022.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.