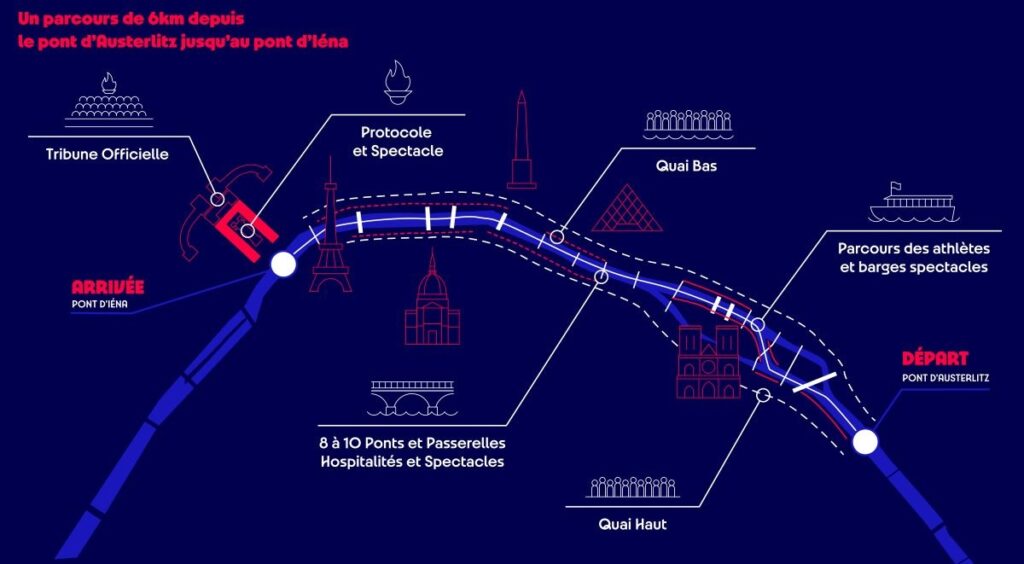

On July 26, the 2024 Olympic Games opened in Paris with a pageant staged on the Seine. For the Parade of Nations, tour boats ferried athletes from the Pont d’Austerlitz to a temporary rostrum in front of the Eiffel Tower where they were greeted by President Emmanuel Macron and VIPs (Fig. 1). This procession was punctuated by twelve vignettes staged at various points along the river that, the ceremony’s artistic director Thomas Jolly claimed, celebrated France’s history and diversity.[1] Lady Gaga welcomed the world to Paris, while at the Conciergerie the band Gojira and decapitated Marie Antoinette figures offered a heavy metal rendition of the Revolutionary anthem “Ça Ira” animated by an explosion of blood red streamers. Down river, soprano Axelle Saint-Cirel, bedecked in the Tricolore as a Black personification of the French Republic, sang “La Marseillaise” from the roof of the Grand Palais. Along the way, the procession passed towering female heads taken from paintings like Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Madeleine (1800). The event culminated with the Olympic flame giving lift-off to a hot air balloon in homage to the inventor Montgolfier as Celine Dion sang Édith Piaf’s “Hymne de l’amour” atop the Eiffel Tower.

From the time that French Olympic authorities first announced the idea for a waterborne opening ceremony in December 2021, there was a lot of talk about history. Official media declared that this was the first Olympic opening ceremony staged outside of a stadium and offered dazzling digital renderings of the yet-to-be-realized spectacle.[2] Jolly and his creative team, which included the historian Patrick Boucheron, also talked up the spectacle as being unprecedented even as they admitted to taking inspiration from the 1989 Bicentennial and the 2012 London Olympics.[3] History remained a topic of discussion in the ceremony’s aftermath as controversy ensued about the representations of Marie Antoinette and the meaning of a certain tableau vivant.[4] The mounting fray online of negative viewer reactions, art historical interpretations, and outrage stirred up by French and American politicians forced Jolly and the Games’ organizers to offer clarifications.[5]

Largely missing from the conversation, though, is a longer historical perspective. One of the few media sources in either French or English to attempt this was a New York Times article by Catherine Porter. Referencing a festival from 1739, she noted that “the Seine has not seen such a celebration in 285 years, since King Louis XV celebrated the marriage of his daughter to the prince of Spain.” While this statement is factually incorrect–pageants were subsequently staged on or along the Seine in 1763, 1770, 1801, 1804, 1810, and 1896–it rightly invites us to consider the 2024 opening ceremony in light of its eighteenth-century predecessors.

As a historian-observer-participant who watched the opening ceremony live from temporary bleachers by the Pont Alexandre III, I was delighted to experience the spectacle as it continued a long history of pageantry on the Seine. And yet the Olympic fête also departed from its early modern precursors in some fundamental ways–particularly in its use of the river–that caused it to be less successful both as a live-televised spectacle and as a medium of political communication.

The opening ceremony most strongly recalls two waterborne festivals staged in eighteenth-century Paris. One is the celebration given by the Spanish ambassadors to France in 1730 to belatedly mark the 1729 birth of Louis XV’s first son, the dauphin. The other, mentioned in Porter’s New York Times article, is the 1739 festival organized by the city of Paris to honor the marriage of Louis XV’s oldest daughter, Princess Louise-Élisabeth, to the Infante of Spain. While elaborate displays had been staged on the Seine since the 1540s, these two celebrations were unprecedented in their scale and sheer spectacle. Both were staged in the very center of Paris on a stretch of the river bracketed on the water by the Pont Neuf and Pont Royal, with the Louvre and Institut de France serving as monumental backdrops from the Right and Left Banks, respectively. This is almost exactly the site where, at the 2024 Olympic Opening Ceremony, Aya Nakamura danced with the Republican Guard.

Turning to the Seine was a matter of both practicality and theatricality, as few spaces in early modern Paris could easily or safely accommodate elaborate ephemeral displays and large crowds. A painting from 1754 by Nicolas Jean-Baptiste Raguenet illustrates the dangerously cramped conditions of the Place de Grève where pyrotechnic celebrations were often staged. In 2024, the Seine again offered an unparalleled amount of space for both the display and spectators. In the name of democratizing the Games, Olympic authorities had initially planned to welcome 600,000 people to the riverbanks for the opening ceremony. Even when this number was later reduced to 300,000 viewers, the figure was still far greater than the number that could be accommodated by Paris’s largest arena, the Stade de France (capacity: 80,000 seats).[6] When it came to the Seine’s theatrical appeal, the artistic director, Thomas Jolly, was drawn not just to the river’s size and historic monumentality but also to its mythological significance, going so far as to claim the river’s namesake Gallo-Roman goddess as his muse.[7]

Festival organizers in the eighteenth century exploited the Seine to dramatic effect in ways that echoed in 2024. In 1730, the celebration of the dauphin’s birth culminated in an elaborate fireworks display launched from a vast floating garden designed by the architect-scenographer Jean-Nicolas Servandoni (Fig. 2).[8] At the center stood a mountain constructed of wood and papier-mâché whose twin peaks reached upwards of 80 feet, flanked by groves of trees and parterres de broderie traced out in grass and colored sand. The display was animated by people concealed within the mountain who waved long strips of white gauze to create the illusion of waterfalls and a pyrotechnic rainbow that graced the sky above. At the spectacle’s climax, night magically became day as an artificial sun rose from between the twin peaks. This garden reappeared in 2024 as a stage for BMX riders and breakdancers costumed in white pantaloons.

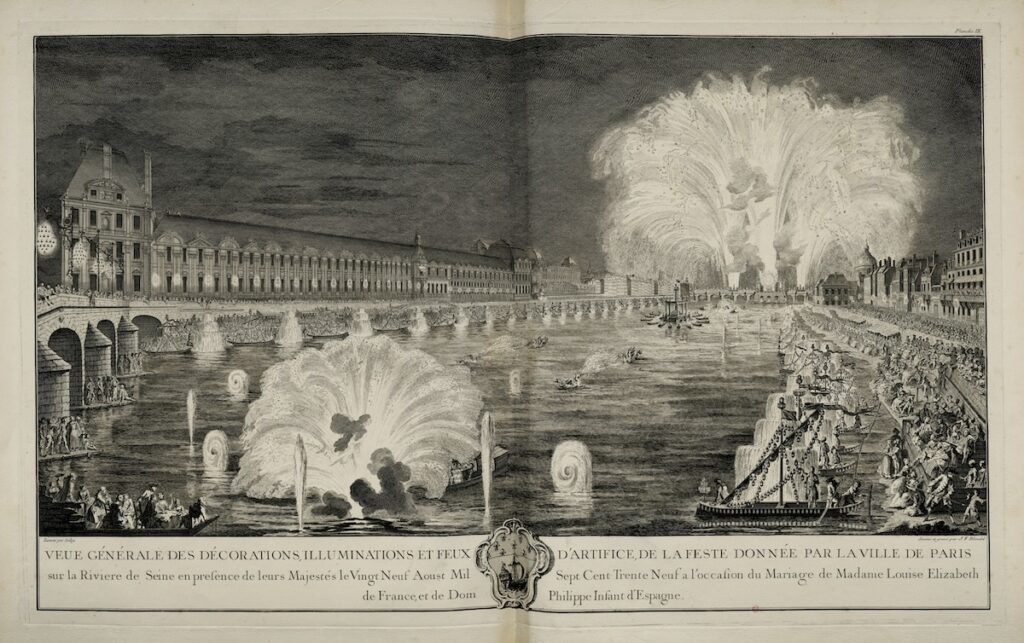

In 1739, the wedding celebration for Louise-Élisabeth also culminated with a pyrotechnic spectacle on the water (Fig. 3).[9] On this occasion, live music was integrated into the display by means of an orchestra that played from an illuminated pavilion constructed from wood and painted canvas that floated on the river atop two boats concealed under an outcropping of artificial rocks. The Seine was further animated by small boats strung with lanterns and several fire-breathing sea monsters. In a foreshadowing of the seating arrangements at the opening ceremony, the royal family watched the spectacle from a special balcony at the Louvre, with members of the nobility seated nearby on a rostrum set up alongside the palace, while on the quays the public stood or crowded onto temporary bleachers. In the engraving depicting the scene, the view of the celebration is spectacular but not untroubled. Amidst the joyous crowds, a guard uses his spear to drive away a child clothed in rags. The scene calls to mind the policing measures undertaken to secure the Seine and the aggressive action taken by government authorities to remove unhoused people from Paris in preparation for the Olympics.

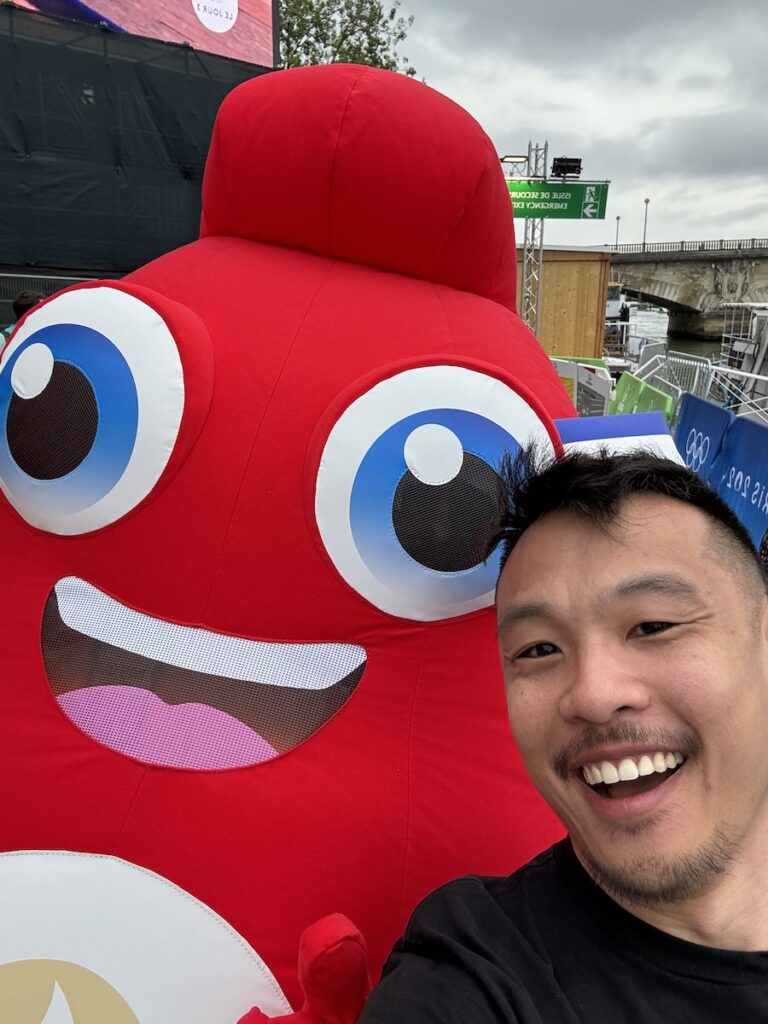

For all of the parallels, the opening ceremony differed from its eighteenth-century predecessors in one crucial way: its use of the Seine. Rather than stage the festival in one section of the river as had been done in 1730 and 1739, Jolly and his team dispersed the event along a three-mile stretch. Doing so took advantage of the river’s spaciousness and offered greater spectator capacity, but it compromised the ceremony’s spatial, visual, and narrative integrity. From where I sat, the Seine felt surprisingly small as viewers were restricted to moving within the section for which they were ticketed. Layers of fencing and multiple security checkpoints further isolated spectators from each other and the city more generally. The result was the uncanny feeling of being confined in an open space and a visual monotony that set in even when things were happening on the river or being broadcast on the giant screens that had been erected along the Seine. Still, the quays vibrated with an expectant energy and the overall atmosphere was one of fraternité that only comes from collectively experiencing a global media event: people chatted with strangers from other countries, volunteers handed out miniature flags, and the giant red Phyrges, the Revolutionary caps turned official Olympic mascots, took selfies with excited spectators (Fig. 4).

The heavy reliance on screens to broadcast performances happening live on distant parts of the Seine detracted from the in-person viewing experience. Across the three-hour ceremony, I actually saw very little happen in person. The Parade of Nations and the Olympic flame all passed by me, but like millions of other people around the world I watched the ceremony on a screen. Even from their privileged seating positions by the Eiffel Tower, President Macron and VIPs like Anna Wintour experienced most of the ceremony tele-technologically. The democratization was striking: the king’s central authoritative gaze replaced by the omnipotent view of the television camera.

The ceremony also suffered from a lack of narrative coherence, and the expansiveness of the aquatic stage did not help matters. Unlike royal festivals where the monarch’s glory served as the central organizing idea, the opening ceremony had no single overarching concept that was either immediately legible to a global audience or strong enough to unify its diverse parts. Reflecting at a press conference on the ceremony’s larger meaning, historian Patrick Boucheron stated, “there is one message: yes, despite everything, we can still live together.”[10] This is a laudable sentiment, but it was not sufficient to cohere a spectacle of this magnitude. Spaced far apart on the river with only a vague notion of social harmony to unite them, the different vignettes were not visually or conceptually coherent enough to create a throughline that could easily be followed down the Seine. In the end, this left too much room for misinterpretation.

One of the more historically insightful moments was the day after the opening ceremony. Walking along the Seine, I watched crews disassemble the bleachers and decorations (Fig. 5). At the Conciergerie, workers on cherry pickers hosed down the façade to remove red streamers, while near the Tuileries the large heads of Benoist’s Madeleine and a female figure from a Georges de la Tour painting had already been partially dismantled, with plywood panels and metal studs in plain view (Fig. 6). The artifice was revealed, a reminder that pageants do not magically appear but rather are willed into existence by people who work largely unseen and unacknowledged. Ultimately, the opening ceremony, as the latest successor to waterborne festivals past, is a reminder of pageantry’s enduring allure as a medium. The monarchy is long gone, but its ceremonial trappings continue to be repurposed and reimaged to new ends.

Matthew Gin is Assistant Professor of Architectural History at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, NC

[1] “A Celebration of Our Shared Humanity” Olympic Review 122, June 2024, 34, https://olympicreview.touchlines.com/122/1-1 (all web links accessed August 28, 2024).

[2] “Une cérémonie dans la ville” in Le programme officiel: Jeux Olympiques de Paris 2024 (Chasnais: Imprimerie Pollina, 2024), 38.

[3] Ariane Chemin and Franck Nouchi, “Paris Olympics opening ceremony’s writers: ‘If it’s only there to produce ephemeral glitz, what’s the point?’,” Le Monde, July 16, 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/sports/article/2024/07/16/paris-olympics-opening-ceremony-s-writers-if-it-s-only-there-to-produce-ephemeral-glitz-what-s-the-point_6686013_9.html

[4] Thomas Adamson, “Drag queens shine at Olympics opening, but ‘Last Supper’ tableau draws criticism,” Associated Press, July 27, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/olympics-2024-drag-queens-opening-ceremony-c635aa276be1147e4643231bdbe5478e

[5] Yan Zhuang, “An Olympics Scene Draws Scorn. Did It Really Parody ‘The Last Supper’?,” New York Times, July 28, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/28/sports/olympics-opening-ceremony-last-supper-paris.html

[6] “France downsizes Paris 2024 opening ceremony crowd to around 300,000 spectators,” Associated Press, January 31, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/olympics-paris-oepning-ceremony-downsizing-0cc56fee1fb6a980274c67546c24bc10

[7] Gaby Wood, “Thomas Jolly is Masterminding the Most Complex Olympics Opening Ceremony of All Time,” Vogue, May 30, 2024, https://www.vogue.com/article/thomas-jolly-profile-paris-olympics-opening-ceremony

[8] Nicholas Lenglet Du Fresnoy, Description de la feste et du feu d’artifice qui doit être tiré à Paris, sur la Riviere, au sujet de la naissance de Monseigneur le Dauphin par ordre de Sa Majesté Catholique Phlippe V… (Paris: Pierre Gandouin, 1730).

[9] Description des Fêtes données par la ville de Paris, à l’occasion du mariage de madame Louise-Elisabeth de France, & de Dom Philippe, infant & grand amiral d’Espagne, les vingt-neuvième & trentième août mil sept cent trente-neuf (Paris: Mercier, 1740).

[10] Quoted in Paul Ackermann, “‘Une histoire au présent, diverse’: Patrick Boucheron donne sa vision de la cérémonie d’ouverture des JO,” Le Temps, July 26, 2024, https://www.letemps.ch/monde/europe/une-histoire-au-present-diverse-patrick-boucheron-donne-sa-vision-de-la-ceremonie-d-ouverture-des-jo

Cite this note as: Matthew Gin, “Liberté, Égalité, Festivité: The Opening Ceremony of the 2024 Paris Olympics,” Journal18 (September 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7411.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.

Pingback: Professor’s Article Places Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony in Historical Context – College of Arts + Architecture