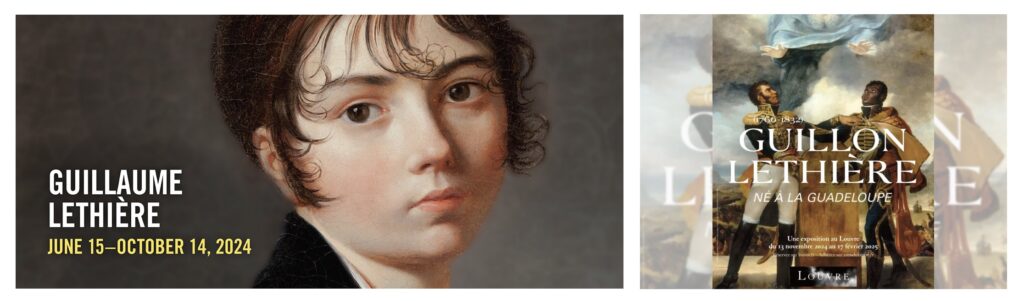

Guillaume Lethière (The Clark Art Institute, June 15-October 14, 2024)

Guillon Lethière, né à la Guadeloupe (Musée du Louvre, November 13, 2024-Feburary 17, 2025)

Since last June, museumgoers on both sides of the Atlantic have been able to discover the extraordinary life and career of the neoclassical painter Guillaume Guillon Lethière (1760-1832) through an exhibition co-organized by the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts and the Musée du Louvre in Paris (Fig. 1). The exhibition’s transatlantic tour is fitting for its subject, a Creole artist who himself crossed the Atlantic as a young man and until now was under-studied by art historians and unheard of by a wider public.[1] Lethière was born in the French Caribbean colony of Guadeloupe in 1760 to Pierre Guillon, a white French plantation owner, and Marie-Françoise Pepeye, an enslaved woman of mixed race.[2] In 1774, Guillon brought his third natural child (le tiers, hence “Lethière”) with him to the metropole. In France, Lethière would find dazzling success as a painter and an institutional leader. While Lethière would never traverse the Atlantic again, he sustained conflicting interests in the Caribbean. On the one hand, after his father’s death, Lethière and his sister became the owners and beneficiaries of Guillon’s plantation. On the other, Lethière condemned slavery—a position visually affirmed in his 1822 Oath of the Ancestors, a remarkable painting secretly sent to Port-au-Prince by Lethière that celebrated Haiti’s abolition of slavery and independence from French colonial rule. Lethière’s story illuminates the symbiotic relationship between art and empire, especially its knotty contradictions.

The exhibition’s 432-page catalogue (printed in English and French editions) untangles many of these intricacies in impressive depth and will remain an invaluable resource for scholars on not only Lethière, but late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Creole identity and French Caribbean networks more broadly. These themes were central to the Clark’s illuminating presentation of the exhibition, Guillaume Lethière, co-curated by Esther Bell and Olivier Meslay (also the catalogue’s editors). The curators’ sensitivity to the complexities of Lethière’s biography began with the title itself, as they dropped “Guillon” from Lethière’s name. This is a subtle but significant choice as Lethière did not include Guillon in his name until 1799 when his father legally recognized the artist as his son.

Organized chronologically, the Clark’s exhibition opened by contextualizing Lethière’s colonial origins with a nineteenth-century map of Guadeloupe, embellished with chilling vignettes of plantation labor as the first object (Fig. 2). Lethière’s development as a history painter was then plotted. The first gallery in particular included a satisfying progression of early preparatory works for his 1811 canvas, Brutus Condemning his Sons to Death. From this point on, the exhibition simultaneously traced his integration within powerful French artistic and political circles, reaching a crescendo with Lethière’s official 1807 portrait of Joséphine Bonaparte—a mixed-race, Guadeloupe-born Creole artist painting a white, Martinique-born Creole empress married to the man who reinstated slavery in French colonies.

Joséphine, Empress of the French alone affords tremendous commentary on the presence and influence of Caribbean-born people in early nineteenth-century French society. However, this subject was further interrogated in the following gallery, which was devoted to artworks by and representations of Lethière’s Creole contemporaries. Beyond shedding light onto lesser known figures, such as the painter Benjamin Rolland, and paying tribute to more familiar characters, like the violinist and composer Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George (the subject of Chevalier, a 2023 American film), this section effectively challenged the persistent assumption that only white people born within the borders of France could shape French culture.

After examining Lethière’s directorship at the Académie de France in Rome (1807-1816), a post attained for him through his close friend Lucien Bonaparte, focus turned to Lethière’s Oath of the Ancestors. While the loan of Lethière’s Oath was secured from the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien for both exhibitions, the important painting was unable to travel due to Haiti’s current political and humanitarian crisis. This absence can be seen as a poignant reminder of the ongoing legacy caused by the debilitating indemnity imposed onto Haiti by France in 1825 (two years after the Oath’s arrival), which many scholars cite as the origin of Haiti’s enduring economic deficit and resulting political turbulence.[3] The Clark’s solution was a color reproduction lightbox, somewhat disappointingly reduced in scale from the monumental canvas measuring about 11 by 7 ½ feet (Fig. 3). As visitors moved toward the glow of the reproduced Oath, the Haitian Revolution was contextualized through printed portraits of its key figures as well as the Clark’s 1818 painting by Adolphe-Eugène-Gabriel Roehn of the swearing in of Haitian president Jean-Pierre Boyer—the recipient of Lethière’s Oath.

The remaining galleries explored Lethière’s role as a teacher (with emphasis on his female students) and his final works before his death in 1832, which included preparatory drawings for The Death of Virginia (1828). Developed by Lethière over four decades, the gruesome history painting shows the aftermath of Virginia’s choice of death over bondage.[4] The exhibition’s concluding wall text, “Legacy,” left visitors with a powerful quote by the contemporary Guadeloupean artist Richard-Viktor Sainsily-Cayol critiquing Lethière’s conspicuous omission from French history, “…Lethière was one of those ‘men of color’ who, for a time, emerged from the fray to serve the Nation they thought was theirs. In this respect, keeping him out of the ‘history’ that he himself contributed to writing through his work seems surreal to me.”[5]

Whereas the Clark’s exhibition thoroughly immersed visitors in both Lethière’s colonial and metropolitan worlds, the Louvre’s iteration sought to rectify Sainsily-Cayol’s observation and reestablish Lethière’s place within France’s art historical canon. Curated by Marie-Pierre Salé, the Louvre’s exhibition was thematically organized into six sections that were unfortunately divided across two spaces, separated by a heavily trafficked hall at the Sully wing’s entrance. Some of Lethière’s most important history paintings—which were unable to travel to the Clark because of their size—are held in the Louvre’s collection. However, due to the low ceilings of this particular exhibition space (most often used for shows spotlighting works on paper), works like Philoctetes on the Island of Lemnos were awkwardly installed (Fig. 4). These galleries even made the installation of the Louvre’s Brutus and Virginia impossible, and so these paintings—on view elsewhere in the museum’s permanent collection galleries—were replaced by a close-to-scale, projected video panning across each canvas.

The exhibition’s first gallery opened with a Roman-inspired, white marble bust of Lethière (commissioned by the artist himself), confirming his position among France’s cultural pantheon. Portraits of Rolland and Alexandre Dumas père were also placed in this gallery (see Fig. 4, with Dumas père’s bust near Philoctetes, for which his father modelled), suggesting that Lethière was not the only influential, mixed-race man in nineteenth-century France. Regrettably, however, the impact the Clark made with its gallery devoted to Caribbean communities was lost in this small display. The exhibition’s first half continued with Lethière’s political works, curiously excluding Joséphine, and ended with his mentorship of women artists. Sadly, this is where the show ended for many visitors, who were absorbed by the bustling hall separating the two parts of the exhibition.

The show’s second half began with Lethière’s relationship with classicism, including two works (a late Poussin painting and an ancient Greek vessel) from his own art collection, now in the Louvre. Attention then turned to his two most significant history paintings, Brutus and Virginia, through a beautifully installed but somewhat confusingly ordered display of preparatory works leading up to the video of the finished canvases.

A replica of Lethière’s Oath concluded the exhibition. His signature for the painting, found at the base of the plinth, served as the Louvre exhibition’s title, Guillon Lethière, né à la Guadeloupe—a proud declaration of Lethière’s Caribbean roots. The canvas was represented through a full-scale, black-and-white vinyl reproduction in addition to a smaller color version that broke down the painting’s symbolic elements (Fig. 5). In terms of situating the work within a larger Haitian context, the Louvre included fewer objects than the Clark: only a bust of Boyer was installed next to a timeline, but there was a listening booth featuring commentary from French historian Frédéric Regent and Jean-Claude Legagneur, curator at the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien (only in French).

While this dedicated space of the exhibition conveyed the epic nature of Lethière’s Oath, the Louvre missed an opportunity to fully reckon with Lethière’s Creole identity and France’s colonial project. Nevertheless, the historic institution’s celebration of a mixed-race painter from Guadeloupe marks significant progress in a country that has consistently turned a blind eye to its colonial past and legacy. With the spotlight rightfully recast upon Lethière, both exhibitions will no doubt catalyze important new scholarship and projects on the Creole artist and the transatlantic contexts that shaped his life.

Jennifer Laffick is a PhD candidate in art history at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, TX

[1] Scholarly interest in Lethière has grown over the past three decades on both sides of the Atlantic. Geneviève Capy and Gérard-Florent Laballe established the Association des Amis de Guillaume Guillon Lethière, which organized exhibitions on the artist in both Guadeloupe and France throughout the 1990s. Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby’s multiple publications on Lethière’s Oath of the Ancestors have shaped Anglophone scholarship on the Creole artist. See Geneviève Capy, “Guillaume Guillon-Lethière, peintre d’histoire (1760-1832)” (PhD diss., Université de Paris 8, 1997); Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, “Revolutionary Sons, White Fathers, and Creole Difference: Guillaume Guillon-Lethière’s “Oath of the Ancestors” (1822),” Yale French Studies 101 (2001): 201-226; and Chapter 2, “Haiti’s Ancestors” in Grigsby, Creole: Portraits of France’s Foreign Relations in the Long Nineteenth Century (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2022), 31-66.

[2] Because Lethière’s baptism is absent from the parochial registry, it is likely that Marie-Françoise was enslaved when Lethière was born. Due to Code Noir laws of the era, because of his mother’s enslaved status, Lethière would have been born into slavery. This issue is examined in Esther Bell’s essay, “The Worlds of Guillaume Lethière,” in Guillaume Lethière, ed. Esther Bell and Olivier Meslay (Yale University Press, 2024), 20.

[3] A 2022 essay published by the New York Times shed light on this history of Haiti’s forced loan repayments for a wide audience. Catherine Porter, Constant Méheut, Matt Apuzzo, and Selam Gebrekidan, “The Root of Haiti’s Misery: Reparations to Enslavers,” New York Times, May 20, 2022.

[4] In his catalogue entry on Virginia, Olivier Meslay suggests that the painting’s Roman subject may have had personal resonances for Lethière. Because her mother was enslaved, Virginia herself was considered enslaved, a system that resembles the Code Noir legal doctrine that likely shaped Lethière’s youth in Guadeloupe. Olivier Meslay, “Brutus and Virginia: Lethière’s Enduring Subjects,” in Bell and Meslay, ed., Guillaume Lethière, 155-56.

[5] Richard-Viktor Sainsily-Cayol, “Guillaume Guillon-Lethière: La posture insolite ou l’imposture,” in L’insolite dans l’art, ed. Dominique Berthet (L’Harmattan, 2013), 163-64, quoted and translated in Bell, “The Worlds of Guillaume Lethière,” 41.

Cite this note as: Jennifer Laffick, “Lethière in Williamstown and Paris: A Transatlantic Exhibition Review” Journal18 (February 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7672.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.