Exotic? Switzerland Looking Outward in the Age of Enlightenment, Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, September 24, 2020 – February 28, 2021.

Curated by Noémie Etienne, Claire Brizon, and Chonja Lee in collaboration with Etienne Wismer and Sara Petrella. Scenography: Atelier Frédéric Dedelley in collaboration with Jocelyne Fracheboud.

Interactive visit of the exhibition online.

The first room of the exhibition Exotic? Switzerland Looking Outward in the Age of Enlightenment, on view until February 2021, gathers a multitude of objects from the collections of the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne (Fig. 1). What are these objects? What among them is considered “art,” and what is not? What is old, and what is new? No accompanying information is provided, except in the form of a QR code granting access to a list of the room’s contents and to the series of questions that reverberate throughout the space in the form of a sound installation. The effect of this display is unsettling. It introduces the exhibition curated by a group of scholars at the University of Bern whose research focuses on the global and colonial histories of the Old Swiss Confederacy between 1660 and 1815 (today’s Switzerland, with the addition in 1815 of Geneva, Neuchâtel, and the Wallis).

The starting point for this project was a lacquer commode in the collection of the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. I came across this commode in 2015, while I was a postdoctoral research fellow at the Getty Research Institute. It constitutes, in part, an old Japanese lacquer fragment that is inserted yet also concealed within a piece of French furniture. Other parts of the object are made up of a type of French imitation lacquer known as Vernis Martin. Why was this commode made in this way, I asked myself? Why even bother to preserve and display such a foreign fragment in a French eighteenth-century setting? Why try to imitate the gloss and dark black of Asiatic lacquer? Consulting the Encyclopédie, I noted that the Chevalier de Jaucourt, who wrote the entry on “Lacque” (Lacquer), described it as “un art exotique” (an exotic art) in 1766. What did the term “exotic” mean in eighteenth-century France, and what does it mean now? Thus, the idea of the exotic became the basis of a long-term collaborative research project focusing on the presence and imitation of extra-European objects and techniques in Europe.

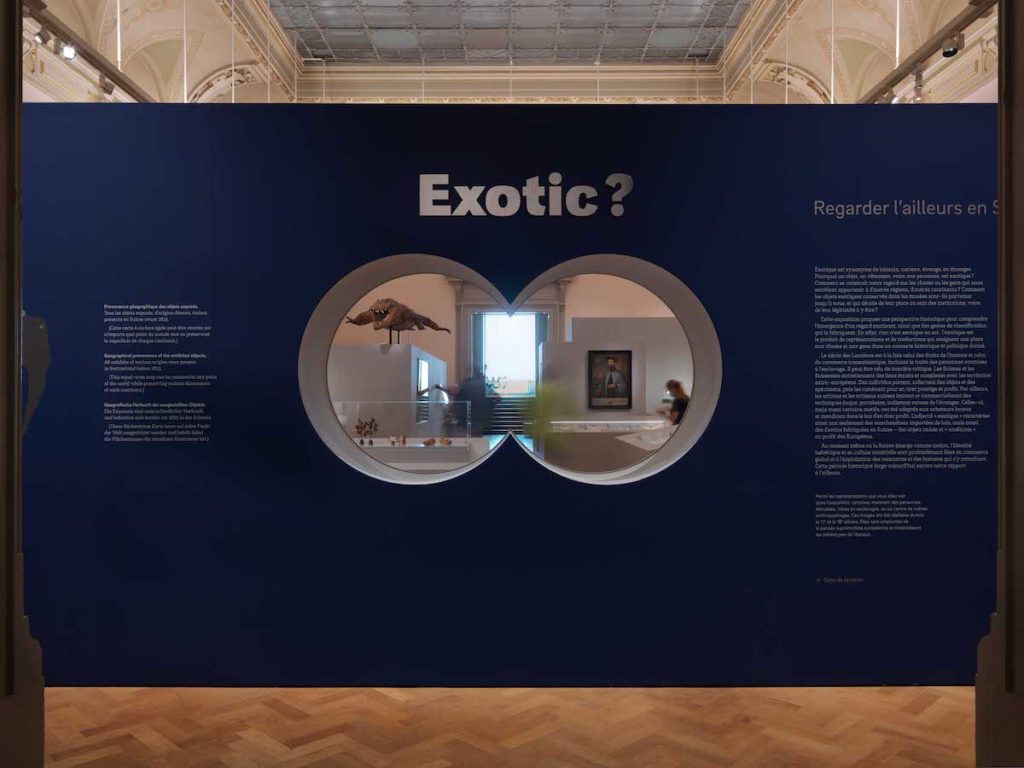

The main argument of the Lausanne exhibition is also one of our research conclusions. From our perspective, the eighteenth-century idea of the exotic is understood here as implying objects that came from distant realms and, moreover, were likely to be imitated, “improved,” and exploited. Moreover, our argument is that nothing is intrinsically “exotic” per se: rather, the exotic is generated through processes of representation, imitation, and commodification, through which people and things are assigned a specific place in a given historical, geographical, and political context. (In his entry on Lacquer, Jaucourt describes its manufacture in Asia but then immediately provides a much longer recipe for imitating it in France, despite the absence of one of the principal botanical components.) We consequently organized the display of the exhibition’s main room into four sections: leaving, collecting, exploiting, and selling. Within these processes of mediation, the cultural identity, geographical origin, gender, and social status of the gazing subject determine to a large extent his or her perspective. In the second room of the show, two open circles in the wall reminiscent of binoculars designed by Atelier Frédéric Dedelley materialize this idea of viewpoint or position (Fig. 2).

What does Switzerland do to Global (Art) History?

Returning to Switzerland after my time at the Getty, I decided to make my research questions even more specific and to work with local collections. What did “the exotic” stand for in Switzerland during the so-called Age of Enlightenment? How should this term be defined, and what does it encompass in a specific geographical (Swiss) and historical (Enlightenment) context? Until the opening of our show and the publication of our book, there was simply no exhibition, monograph, or comprehensive research project exploring the connection between the Old Swiss Confederacy (including connected cities such as Geneva, at the time an independent Republic) and other continents during the eighteenth century. In fact, books in the fields of global history or global art history tended to focus on European empires formed around countries with maritime borders and centralized governments such as France and England. Yet is it productive to think about colonialism or racism with another type of geography or polity? What could Switzerland—a small country with no access to the sea, no international trading companies, no colonial empire—bring to the discussion?

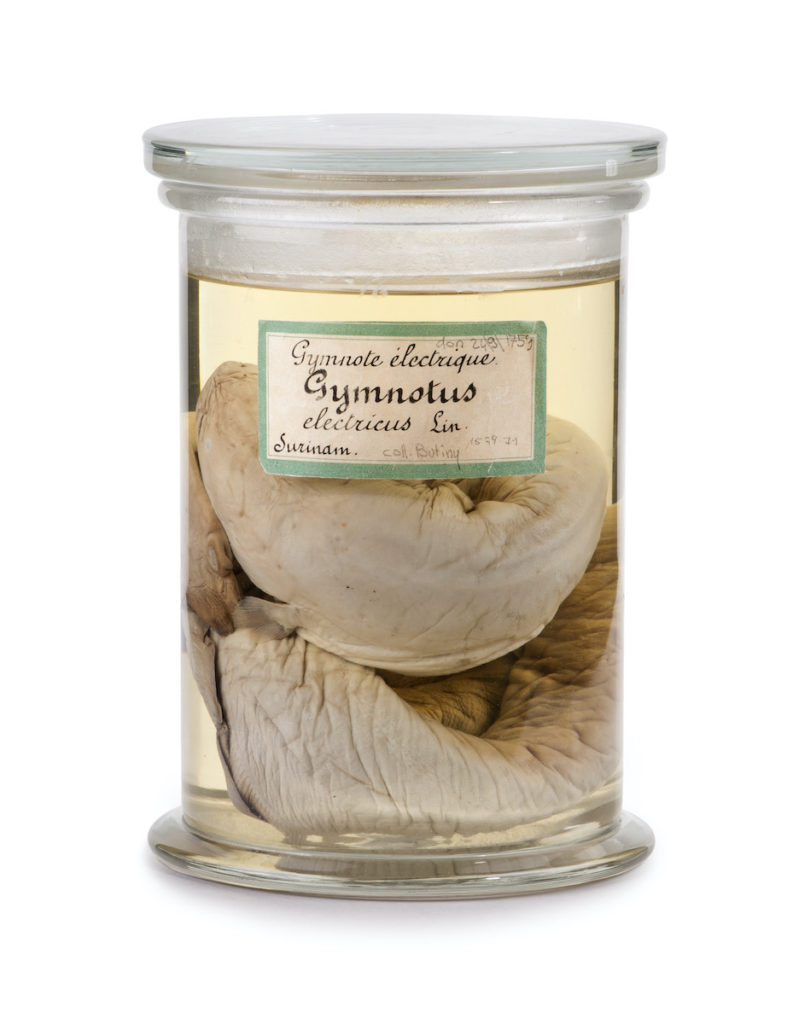

Our investigation, which also involved students taking classes at the University of Bern, has brought to light scores of objects, including artworks, artifacts, natural specimens, books, and other things (Fig. 3). In the second, large room of our show, 150 objects, coming from more than 30 institutions, are shown (Fig. 4). All were present in Switzerland before 1815, and many were made there. We consider these artifacts to be traces of the many suppressed (hi)stories that needed to be told. One such object may exemplify our approach: the gymnotus, an electric eel preserved in a glass jar in the Natural History Museum of Geneva (Fig. 5). It was donated in 1759 to the Bibliothèque de Genève by Ami Butini, a Genevan and a colonist who had settled in Suriname to expand the sugar trade, which relied on the forced labor of men and women. In all likelihood, the eel was caught (at considerable risk, given its potential to shock) by Butini’s own enslaved people, immersed in rum produced on his plantation, and then shipped to Geneva.[1] The gymnotus has been preserved and, to date, it resides in the laboratories of the museum as a natural history specimen. Yet, from our viewpoint, it also stands for an eighteenth-century artifact whose material features are germane to several disciplines: that the eel itself should have been considered a specimen speaks to the history of sciences in Europe; while its presumed method of capture and preservation evoke the history of slavery.

Indeed, Switzerland is a country often described as having no relation to the trade of enslaved people. This rhetoric is even part of most of the official discourse promulgated by the Swiss government. However, as historians have revealed through archival work since the 1990’s, Swiss people participated, individually and collectively, in the trafficking of human beings, either as providers of financial support or directly as enslavers. The eel gives an additional hint of this connection, suggesting the presence of enslaved people in a plantation owned by a man from Geneva, relying on forced labor and violence for the production of alcohol and for the collection of dangerous natural specimens sent back to his hometown. An object’s multiple layers are comparable to a series of clues that can help us uncover and highlight invisible narratives, thereby elucidating the involvement of Swiss individuals with human subjugation during the Enlightenment.

Changing the focus toward a small, less studied area of the exhibition offers an opportunity to reassess the history of colonialism and its connections to imperialism and nationalism. An interesting example is provided by two Bernese men, who wrote down their observations and also made drawings following their respective trips to North America: Francis Louis Michel and Christoph von Graffenried. Following Michel’s expeditions in 1701 and 1702, von Graffenried, with the backing of the Burghers of Bern, founded in 1704 the colony of New Bern (in present-day North Carolina). An examination of their drawings, together with textual sources, reveals that the adventures of these two Bernese colonists was cut short: the Tuscarora Nation reconquered the land (originally the homelands of Neusiok Indians), sacking the New Bern settlement and capturing von Graffenried, who eventually had no choice but to return to Bern (Fig. 6). Their enterprise was a comparatively small-scale, local one, sustained by a city and a network of religious acquaintances. Indeed, colonial projects can also originate from individuals with access to large financial resources. In our view, to include Switzerland in the panorama of global art history encourages visitors or readers to consider understudied networks of colonial settlement. Thinking about global trade, colonialism, and slavery through the lens of a country without any official empire can also help nuance our conception of such practices, underlining how colonial designs can occur without monarchical or nation-based support.

The third room of our show shifts the visitor’s gaze. Paintings, models of mountains, books, and fossils are exhibited against a green painted background (Fig. 7). Here we explore how, at least in the Swiss case, exoticization processes did not simply apply to “distant” realms. In fact, Switzerland itself became an “exotic” locale during the eighteenth century, following the definition undergirding this research project: a place constructed as strange and exploited as such. For instance, the touristic appeal of Switzerland and the Alps at the time is reflected in an oil painting by the French artist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who travelled to Unspunnen in 1809 to attend a festival organized by the Bernese elites and featuring “traditional” dance, music and costumes (Fig. 8). Such events were part of a larger trend typical of the nineteenth century known as “the invention of tradition” or of a nation in the making, to borrow from historians Eric Hobsbawn and Terence Ranger’s foundational analysis.

Yet, and rather paradoxically, the various elements from which these depictions were fashioned—in particular the Swiss costumes—tell a different story: they offer evidence of the globalization of material culture, specifically cotton. As such, they demonstrate that, already by the late eighteenth century, non-European goods were involved in the formation of “local” identities. Furthermore, such images were occasionally manufactured overseas. A set of costume pictures, for instance, was made in China using reverse glass painting after Swiss etchings that had been specifically shipped so that Asian artisans could copy them: it portrays men and women wearing indiennes and set in hybrid Sino-European landscapes (Fig. 9).

Artistic and commercial exchanges among China, Turkey, and Switzerland were intense from the end of the seventeenth century, in particular in the field of watch making. To give one notable example: Isaac Rousseau, father of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, worked at Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace as a clock regulator, making sure that the clocks correctly indicated the times for Muslim prayer. The conception of Switzerland devised by urban elites, however, was that of a peaceful land whose inhabitants were chiefly involved in cheese-making and farming. Interestingly, Jean-Jacques Rousseau himself played a formative role in diffusing this image abroad, in addition to capitalizing on it.

What is to be Seen – and What Remains Silent

An exhibition reveals fragments left through history and preserved in institutions or private collections. But what about what is not there? What about losses, missing things, or archives that were not shared? According to Walter Benjamin, a document of culture is always at the same time a document of barbarism.[2] What remains hints at a gaping hole: behind those works that have been preserved are all those that could not be kept or even created. The lifeworlds of women, workers, enslaved people, and others flicker only fleetingly in the few surviving pictures and archival materials.

The massive absence of objects, images, and information in our exhibition is addressed through the work of contemporary artists. Some pieces were made for the show itself, as is the case with Disappearing Africans (2020), a film and installation by Senam Okudzeto. In her work, Okudzeto uses her own body, which slowly disappears from the screen through the process of a black face realized on her skin by a white male painter. Souvenirs d’Haïti (2020) by Fabien Clerc consists of a set of porcelains from Limoges on which images of the Haitian Revolution are represented: they are ghosts, palimpsest memories of another revolution that shaped history and led to the (temporary) abolition of slavery and, paradoxically, reparations for enslavers. Installations by Susan Hefuna (2015), finally, comprise delicate shadows that “write” through a glass panel on the wall words such as: time, trace, truth, silence.

An exhibition is itself an archive, a narrative full of losses and shadows. In his contribution to the exhibition catalog, Denis Pourawa, an artist from New Caledonia, describes his encounter with a ceremonial ax known as a Nââkwéta, offering us his account of its origins. While handling the object he attached a small piece of cotton yarn from his own scarf, which we decided to leave on the object (Fig. 10). Pourawa also created a piece of oral poetry used as a sound installation in the exhibition, entitled Poésie sonore des gouffres. By leaving on the Nââkwéta a trace of his interaction that will now become part of its history, he suggests how history itself is not only a narrative of the past: it affects our present, and our future.

The current call to dismantle historical monuments in public spaces has also impacted Switzerland. A statue of David De Pury, an eighteenth-century salesman whose wealth was partly based on the slave trade, was covered in red paint this past summer. Since then, the statue has been cleaned and remains in the center of Neuchâtel. Those who have a stake in keeping this monument argued, characteristically, that “one should not rewrite history.” Yet public statues are not history: they are part of collective memory, that which a society decides to remember and valorize. On the other hand, history can also be described as a collection of factual details put into perspective. However, memory and history are interlinked. The latter should inform the former, in order to make appropriate choices regarding preservation and public space. Among other things, the exhibition Exotic? aims to spotlight and enrich the global history of the Old Swiss Confederacy, in order to facilitate a better-informed shaping of its memory.

Studying colonial history beyond the French or British Empires leads to the discovery of many unknown artists, artefacts, and artworks. The case of Switzerland, for instance, sheds light on understudied patterns of circulation, trade, and land occupation, adding to the (often more successful) narratives of aristocratic or imperial support. It offers a way to escape the tendency to focus on well-known images or artists–which is at risk of a perpetual production of readings and re-readings of the same limited corpus. Yet if Switzerland can do a lot for art history, what can art history possibly do for Switzerland? Historians have explored the connection between the Old Swiss Confederacy and the slave trade since the 1990’s. Their work is based on written sources and published material. By taking into account a broader diversity of media, from drawings to wallpaper, natural specimen to textiles, art historians can enrich those findings through the analysis of complex cultural productions tied to global and colonial history. Art historical research shows how much the construction of an exotic gaze was connected to representational conventions and practices, and how closely global trade was tied to the daily lives of people. Finally, as a discipline focusing on the social life of material culture, art history allows us excavate fragments from the past that can be shared with a large audience, engaging directly with contemporary politics.

Noémie Etienne is professor of art history at the University of Bern

[1] For more about enslaved people as specimen collectors in Suriname: Susan Scott Parrish, “Embodying African Knowledge in Colonial Surinam,” in Agnes Lugo-Ortiz and Angela Rosenthal eds., Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 257–281.

[2] “According to traditional practice, the spoils are carried along in the procession. They are called cultural treasures […]There is no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is never free of barbarism, so barbarism taints the manner in which it was transmitted from one hand to another. The historical materialist therefore dissociates himself from this process of transmission as far as possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain.” Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” in Selected Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott et al., 4 vols. (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), 4:391–392.

Cite this note as: Noémie Etienne, “Exotic? A Curator’s Note,” Journal18 (December 2020), https://www.journal18.org/5426.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.