Two exhibitions. Two catalogues. One theme: “Artist and Empire.” The two exhibitions were held at Tate Britain in London (November 25, 2015—April 10, 2016) and at the National Gallery of Singapore (October 6, 2016—March 26, 2017) respectively. We are now increasingly accustomed to travelling exhibitions, especially for blockbuster shows whose monetary outlay can only be recovered over several venues, sometimes in different continents. But the case of “Artist and Empire” is different. In London this was a ‘minor’ exhibition though it was conceived as part of a series of similar shows aimed at increasing the number of visitors to Tate Britain. The theme is clearly expansive and, for an exhibition held at the heart of Britain’s former empire and in one of its most venerable cultural institutions, virtually guaranteed to be controversial. In Singapore, the exhibition was instead one of the launching events of the new National Gallery of Singapore. In a former British colony turned global megalopolis, the perspective could not be more different.

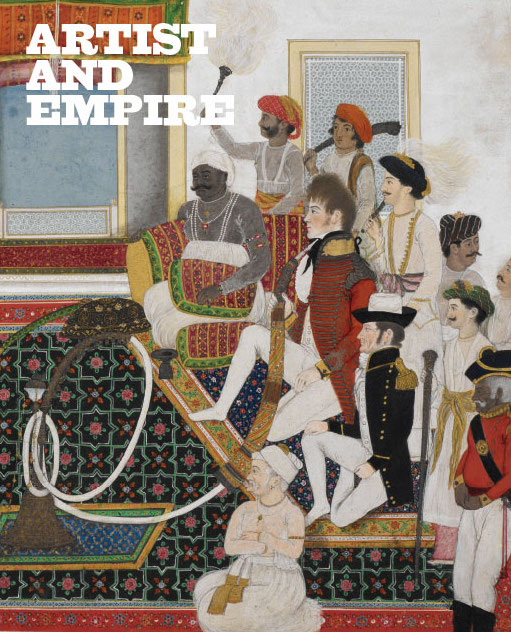

Upon the invitation of the exhibitions’ shared title, perhaps one might start by observing that the British Empire is the only one among the many European imperial ventures that does not need an adjective. Whilst all other empires are prefixed by “German,” “French” or “Belgian,” British imperial history has been characterized by totalizing tendencies that have been difficult to shrug off. Any empire needs an artistic dimension to either create, legitimize, or even critique it. One might consider for instance Johan Zoffany’s Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match, c. 1784-86, a large canvas produced by the German-born English artist during his six-year residence in India. It presents us with a scene taking place at Lucknow where Europeans and Indians intermingle. Much of the action rotates around a cock fight organized by John Mordaunt for his employer, Asaf-ud-Daula, ruler of Awadh. Here the relationship between colonizers and colonized is presented in the style of a classic eighteenth-century conversation piece. It is framed in a quintessential British way to promote a specific view of (benign) empire. Behind the veneer of Zoffany’s somewhat saccharine composition, however, lies a more complex and darker interpretation of the relationship between the historical figures represented. Many of the works in this exhibition are less than transparent records of Empire: they came to shape the very notion of Empire.

The London exhibition, curated by Alison Smith, included a variety of well-known works, among them canvases by Agostino Brunias and Gilbert Stuart, and high-Victorian human-interest pieces such as Eastward Ho! August 1857 and Home Again, 1858 by Henry Nelson O’Neil. A wide range of types of artworks were presented: a clear effort was made to include prints, drawings, maps, gouaches, photographs, as well as sculpture, wood carvings, and bronzes to create a spectacular visual effect. This panoply of objects was mobilized mostly in a historical narrative divided into six large themes. “Mapping and Marking” started the exhibition by conveying the geographical and spatial reach of the British Empire but also the early struggle made by British colonizers to master such spaces. Information and knowledge were central to the following section on “Trophies of Empire.” This was not about war, as one might expect, but about how knowledge of animals, plants, minerals, architecture, and the decorative arts were made useful for the project of Empire. More traditional views on empire-making could be found in a section dedicated to “Imperial Heroics,” though it was the following two sections on “Power Dressing” and “Face to Face” that provided new and original materials. Next to Zoffany’s painting one could admire lesser known works such as three small watercolors on paper, the first Western representations of the Eora Nation—indigenous people living in the area of present-day Sydney. The last section of the exhibition entitled “Out of Empire” was a hurried attempt to deal with postcolonialism and the legacy of empire in postcolonial art more specifically.

A comprehensive catalogue (Fig. 1) provides an excellent guide to a large exhibition that was however rather precise in its remit for at least two reasons. First, all works of art exhibited in London came from British collections, thus reflecting perhaps more what British colonizers wished or thought their Empire might be or look like than anything else. Second, whilst the exhibition visually, aesthetically and even historically chartered empire in its many dimensions, the result was rather insipid in its critical approach. Any postcolonial theorist would have been dissatisfied by a narrative of how empire was made and unmade, rather than how it should be interpreted today. The exhibition’s subtitle “Facing Britain’s Imperial Past” clearly did not deliver on its promise.

This latter point was instead addressed head on by the Singapore exhibition whose subtitle was “(En)countering Colonial Legacies.” In Singapore the exhibition was curated by Low Sze Wee, Melinda Susanto and Toffa Abdul Wahed. It was held in two iconic colonial buildings, the City Hall and the Supreme Court Building that since 2015 have been joined to form the state-of-the-art National Gallery of Singapore. For those who saw the London exhibition, the structure, themes and works included in Singapore were familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. The catalogue’s cover for the Singapore show (Fig. 2) was a print that is part of the 2010 series Undiscovered by artist Michael Cook (b. 1968). Clearly inspired by the homonymous Captain Cook, Michael Cook presents an aboriginal man wearing a Western uniform in the act of “discovering” Australia. It signalled how the Singapore exhibition was less interested in history and more in how Empire shaped colonial life especially in an island state like its own. Here too limitations were visible: the focus on Singapore and the Pacific was to the detriment of other areas such as Africa and, perhaps more surprisingly, parts of Asia (Hong Kong was summarily excluded from the exhibition). A less structured approach based on two broad themes—“Countering the Empire” and “Encountering Artistic Legacies” respectively—struggled to provide a clear sense of thematic division for an otherwise exciting installation.

The difference between the catalogues of the two exhibitions is equally striking. Whilst the London exhibition produced a glossy catalogue of all the works alongside substantial art historical and historical research, the Singapore catalogue presents just a small selection of the works included with short explanations and a couple of great introductory essays. In my visits to both exhibitions—though in no way scientific—I had the impression that the London show was for an older audience whilst the Singapore exhibition aimed to appeal to a younger crowd. Overall one could fall into the trap of condemning the metropolitan inability to provide self-critique, or the former colony’s undigested need to seek identity through art. It is rarely the case that we are presented with an exhibition whose subject has to be reshaped so substantially not just to suit different locations but to make any sense for its viewing public. Empire remains not just a difficult category but also a historical reality that is highly contingent. It needs not just a national adjective but also a geographic compass to guide its understanding and critique.

Giorgio Riello is Professor of Global History and Culture and Director of the Institute of Advanced Study at the University of Warwick

Cite this article as: George Riello, “Exhibiting Empire: Perspectives from London and Singapore”, Journal18 (June 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1850

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.