Cheryl Finley, Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 320 pages

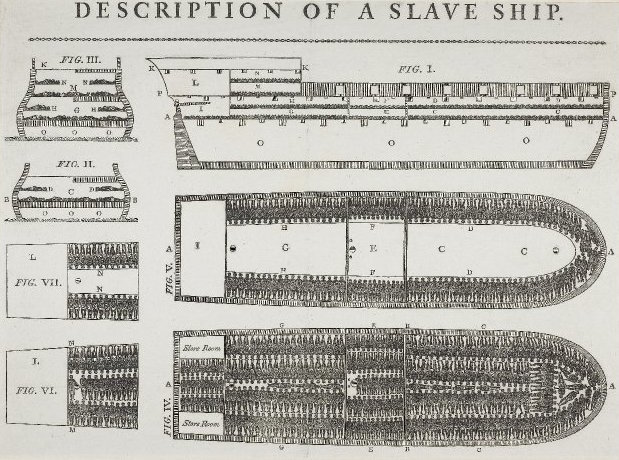

You all know the image. As Cheryl Finley explains, “Refer to ‘that image of the slave ship’ in conversation with just about anyone, and they will know what you are talking about (12).” Finley argues that not only is the abolitionist print, Description of a Slave Ship (1789) (Fig. 1), well-known, but that it has become an icon. Committed to Memory tells the remarkable story of how the schematic rendering of a slaving ship and its human cargo, represented as a sequence of mostly naked, tightly-packed bodies, came to function as a visual formula for artists of the African Diaspora to grapple with the violent history and legacy of the slave trade, and slavery more broadly. Finley organizes her text around the idea of “mneomonic aesthetics, a process of ritualized remembering (5).” She traces how viewers and artists from the eighteenth century to the present have responded to the icon’s visual properties—its depiction of people enduring the Middle Passage as well as its erasure of the historical actors and institutions that put bodies in such ships. She demonstrates how members of the African Diaspora re-made the icon through repetition and modification, transforming it again and again so that the image played a continually active part in their revitalization of history, their reclaiming of memory, and their formation of imagined community.

While Description of a Slave Ship has been well-studied, this is the first book to uncover the icon’s vital importance, not only in the decade when it was made, but from the nineteenth century to the present, as cultural producers used it to help forge a “black Atlantic imagination (9).” As this term suggests, Finley’s theoretical apparatus is grounded in scholarship on the African Diaspora. Drawing from Paul Gilroy’s black Atlantic and Henry Louis Gates’s practice of signifying, she asks how individual artists’ re-imaginings of the slave ship were fundamental to diaspora art practices.[1] Finley also makes a powerful case for scholarship that transcends individual centuries to consider a visual artifact’s entire life history.

Fig. 1. Description of a Slave Ship, 1789. Woodcut, 32.8 x 44.4 cm. British Museum, 2000,0521.31. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Committed to Memory proceeds chronologically. In the first section, “Sources/Roots (1788-1900),” Finley charts how white British abolitionists developed the icon to advocate for the end of the slave trade while also documenting its circulation around the Atlantic to promote abolition. There is much here to interest scholars of the eighteenth century. By presenting a detailed analysis of the specific conditions under which the image emerged, Finley recovers the crucial differences between the first print commissioned by the Plymouth Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST), Plan of an African Ship’s Lower Deck with Negroes in the Proportion of Only One to a Ton (1788); the second better-known version commissioned by SEAST’s London Committee, Description of a Slave Ship (1789); and a third version published in Philadelphia, REMARKS on the SLAVE TRADE (1789). Careful scrutiny of the visual strategies and textual components these groups utilized enables Finley to uncover how the ship icon depicted the slave trade in a way sympathetic to varying abolitionists’ political needs, as well as to demonstrate that repetition with modification has been fundamental to the image from its inception.

Part II, “Meanings/Routes (1900-present),” moves into the twentieth century and discusses the icon’s adoption by African American and Afro British artists who employed it for the work of memory-making and collective expression. For Finley this is a story of reclamation. As artists of the New Negro Arts Movement and then the Black Arts Movement became interested in the history of slavery, the slave ship became a powerful aesthetic tool to make sense of the past and better position African Americans for the future. Slave Ship: A Historical Pageant (1969-1970) by Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) is an especially vivid example of how members of the African Diaspora have utilized the slave ship. The performance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Harvey Theater employed a wooden slave ship as a set, and Baraka not only seated audience members among actors in the hold, but also incorporated smell, sound, and light to create an immersive experience. As Finley argues, because Baraka’s Slave Ship “inserted the voices, desires, movements, and music of resistance that were absent from the static, two-dimensional drawing,” the performance “recast the slave ship icon with an updated purpose fitting for revolutionary times (139).”

The final section, “Rites/Reinventions (1990s-present),” considers contemporary artists’ invocation of the slave ship as a mode of connecting with a distant homeland, as a personal mnemonic for suffering, and as a spiritual artifact. Finley enters the realm of popular culture and public history as the print prompts her to consider the ongoing commodification of sites associated with the slave trade through tourism, namely slave castles. The wide swath of visual and material examples that Committed to Memory brings into dialogue with one another in this section is staggering—from stained glass windows to installations of gingerbread biscuits. Finley is also to be commended for her commitment to take all iterations of the icon seriously, and on their own terms. At some points the wealth of examples can be overwhelming, especially for readers who are not already familiar with African diaspora art. However, thematic groupings and the visual continuity provided by the image itself help to guide the reader, as do anchors provided by more familiar artists such as Betye Saar and Romare Bearden.

Finley’s examination of the multi-layered processes of reinscription and reinterpretation, through which varying makers gave an eighteenth-century print new meanings, provides a welcome addition to multiple fields of scholarship: print history, abolitionist art, African American art history, African diaspora art history, and critical heritage studies. By illuminating the ways artists energized latent possibilities within the print, she enhances our understanding of the original artwork. It is impossible now to view Description of the Slave Ship without seeing the potential for Willie Cole’s scorched ironing boards or Sanford Biggers’ etched glass lotus flowers. The importance of an artwork’s afterlife, and the need to consider secondary makers and later viewers as critical to its meaning, is gaining scholarly currency. Committed to Memory resonates in particular with Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson’s ongoing project “Afrotropes,” which asks scholars to examine the recurrence of visual forms across the afterlife of slavery.[2] The Afrotrope raises questions about “slavery’s perpetual returns,” and encourages juxtapositions across time and space that do not always accord with linear narratives.[3]

Committed to Memory offers a related but different model for those interested in studying a visual artifact’s life cycle. Collectively Finley’s chapters render the print a palimpsest in which past and future commingle, but the book’s chronological progression emphasizes the roles specific patrons, artists, and viewers played in shifting the icon’s form. As a result, the image itself is always present, but its materiality or icon-ness—its potential agency to challenge chronology and enable incredible mobility and mutability—is less fully explored. However, the artistic diversity encompassed by Committed to Memory illuminates powerfully the creativity and commitment of black diaspora artists who, acting as bricoleurs, drew together materials to help make sense of a traumatic past and an all-too-often violent present. As Finley convincingly argues, the slave ship icon’s ultimate message is one of survival.

Jennifer Van Horn is an Assistant Professor of Art History and History at the University of Delaware

[1] Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993); Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

[2] Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, “Afrotropes: A User’s Guide,” Art Journal 76:304 (2017), 7-9; Leah Dickerman, David Joselit, Mignon Nixon, “Afrotropes: A Conversation with Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson,” October 162 (Fall 2017), 3-18.

[3] Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, “Perpetual Returns: New World Slavery and the Matter of the Visual,” Representations 113 (Winter 2011), 1-15; Emma Chubb, “Small Boats, Slave Ship; or, Isaac Julien and the Beauty of Implied Catastrophe,” Art Journal 75:1 (2016), 24-43.

Cite this note as: Jennifer Van Horn, “Committed to Memory: A Review,” Journal18 (December 2018), https://www.journal18.org/3309.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.