Blue Lewoz, Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Paris, France, June 10 – July 23, 2022.

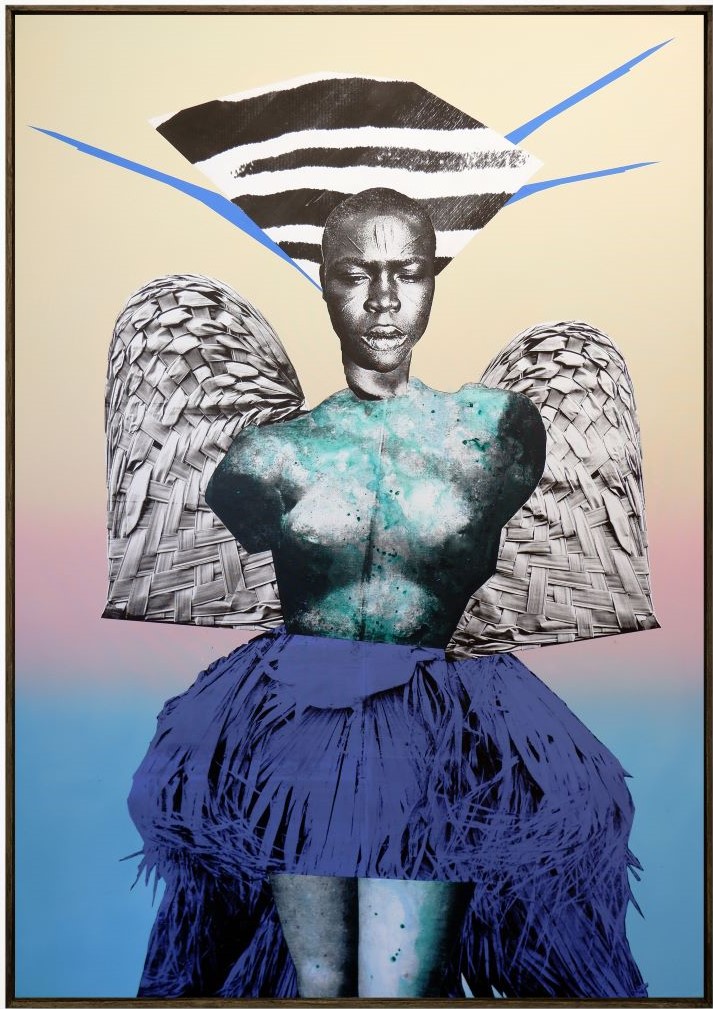

Visitors to Raphaël Barontini’s show Blue Lewoz at Mariane Ibrahim’s Paris gallery this past summer were greeted by the imposing figure of Creole Dancer (Fig. 1). The 9 feet by 6 feet collage of an archival photo of a Black woman, an ancient torso, and woven wings ushered viewers into a Caribbean carnival of the artist’s creation that appropriated and reworked European art history to create a new Caribbean history. The title Blue Lewoz brings together léwoz, the music and dance created by the enslaved people on Guadaloupe, and indigo blue, a dye that was a staple of the transatlantic slave trade. Barontini writes on his Instagram that Creole Dancer was inspired by a 1950 collage by Matisse of the same name, and a tribute to the “Caribbean women and the place of the dance in the Guadeloupean léwoz tradition.” From this twentieth-century inspired work, viewers quickly moved into an alternative history of fashion and luxury of early modern Europe: collages that incorporate Jean-Marc Nattier’s eighteenth-century dresses, Bronzino’s elaborate fabrics, and Elizabethan ruffs. While Barontini’s appropriation and sources stretch wider than the long eighteenth century, many of the fashions in those portraits were the product of, as Alicia Caticha notes, “Atlantic slave trade and a host of other exploitative global networks.” And, as scholars such as Anne Lafont and Mechtild Fend have shown, portraits were often used to construct and highlight whiteness.[1] Barontini’s work reinvents those portraits and, through collage, tapestries, and textiles, celebrates resistance and Caribbean festivals.

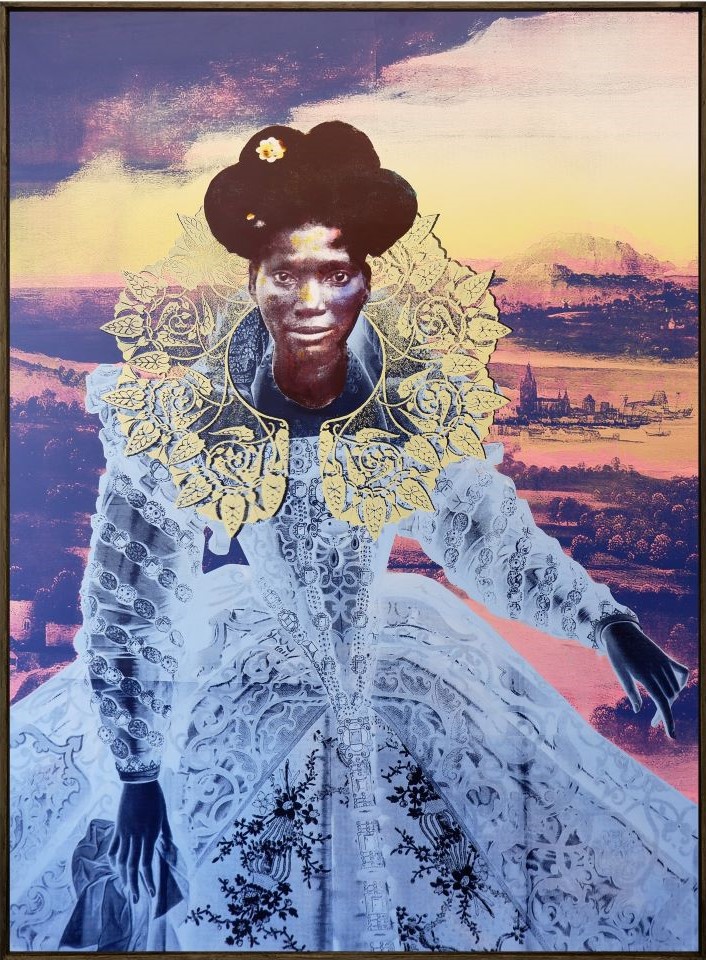

Barontini’s work disrupts European portrait traditions by introducing archival photographs of Black men and women from the Bibliothèque nationale de France, African masks, palm fronds, glitter, and swaths of lace, plaids, and other patterned fabrics. The artist’s interest in these juxtapositions started early. As a student at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he collaged photographs of his friends and family in Saint-Denis, the Parisian suburb where he was raised, with portraits he saw in the Louvre.[2] This practice developed into a more intentional engagement with theories of “creolization,” as well as his family’s connections to Guadaloupe and Réunion, that incorporates both historical and imagined portraits of figures of resistance and revolution: Toussaint Louverture, Solitude, and invented figures like The Lewoz Queen who reigned over Blue Lewoz’s festivities (Fig. 2).

The second-floor installation translated the visual references of the paintings into material ones—flags, Savonnerie tapestries, and wearable items (Fig. 3). Indigo toile de jouy–style curtains framed the large windows overlooking the avenue Matignon below, decorated with African masks, ships, figures from Agostino Brunias’s paintings, and a fist breaking its chains surrounded by a halo of palm fronds (Fig. 4). Barontini describes the curtains as “carnivalesque revenge,” but that description applies to what he did to the whole space.[3] Ibrahim’s gallery resides in a quintessential Haussmann building, and the second-floor space calls to mind Parisian (and white) nineteenth-century salons. Decorated with luxury items reworked with the visual language of the diaspora, it was transformed into a distinctly Black, creole space. A musical score by American hip hop artist Mike Ladd—a frequent collaborator of Barontini’s—that remixes Jean-Baptiste Lully’s Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (1670) with bells and percussion taken from Voudou ceremony music and léwoz festival music filled the room. At the center, two mannequins in silk capes faced each other as if ready to dance. Barontini explains that they “extract the costumes of the paintings into space.”[4] The images on the cape—one a male figure, and the other a female figure—are Barontini’s imagined portraits of maroons, escaped slaves who played a key role in the Haitian Revolution and the slave revolts on Guadaloupe. The female figure is a “Black Minerva,” his homage to Solitude, a pregnant woman on Guadaloupe who fought against Napoleon’s army in 1802 (Fig. 5).

The installation resonates with Barontini’s performance practice, which often includes parades. Along with growing up attending carnival festivals on Guadaloupe and Réunion, Barontini played drums in a carnival band as a teenager. Blue Lewoz’s reference to carnival is typical of the artist’s practice. I first met him in 2020, when he was invited to create an exhibition for Fort Worth Contemporary Arts (FWCA) at Texas Christian University, which coincided with his residency with LVMH at the Heng Long Leather Tannery in Singapore. The resulting show, Caribbean Fantasia, deftly interwove the legacy and history of cowboys of colors in the Fort Worth and the Black heroes of the Haitian Revolution. The show opened with a parade of local Cowboys of Color on horseback, dressed in chaps and kerchiefs and carrying flags designed by Barontini, down the main street of the University to the gallery. They were accompanied by a soundtrack commissioned by Ladd. Upon arriving at the FWCA, the Cowboys dismounted, and ceremoniously removed and hung their costumes in the space alongside a large fabric installation that repeated the imagery on their outfits.[5]

Marika Takanishi Knowles writes that eighteenth-century art and material culture strove to “mak[e] whiteness.” From the literal whitewashing of African or Asian figures in porcelain, to the emphasis on whiteness in portraiture, Knowles points out the numerous and productive ways historians of art and material culture have deepened our understand of the relationship between luxury production, the slave trade, global imperialism, and race. Blue Lewoz, and Barontini’s work more broadly, offers a powerful alternative that makes and celebrates Blackness.

Jessica L. Fripp is Associate Professor of Art History at Texas Christian University, Fort Worth TX

[1] Anne Lafont, “How Skin Color Became a Racial Marker: Art Historical Perspectives on Race,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 51, 1 (2017): 89-113; Mechthild Fend, “Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait d’une Négresse and the Visibility of Skin Color,” in Probing the Skin: Cultural Representations of Our Contact Zone, ed. Caroline Rosenthal and Dirk Vanderbeke (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015), 192-210.

[2] Raphaël Barontini, in discussion with the author, June 2022.

[3] Barontini, discussion.

[4] Barontini, discussion.

[5] The video of this performance and associated works were recently shown at the Museum of Art and Design’s exhibition Garmenting: Costume as Contemporary Art (Mar 12–Aug 14, 2022).

Cite this note as: Jessica L. Fripp, “Blue Lewoz: A Review,” Journal18 (October 2022), https://www.journal18.org/6491.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.