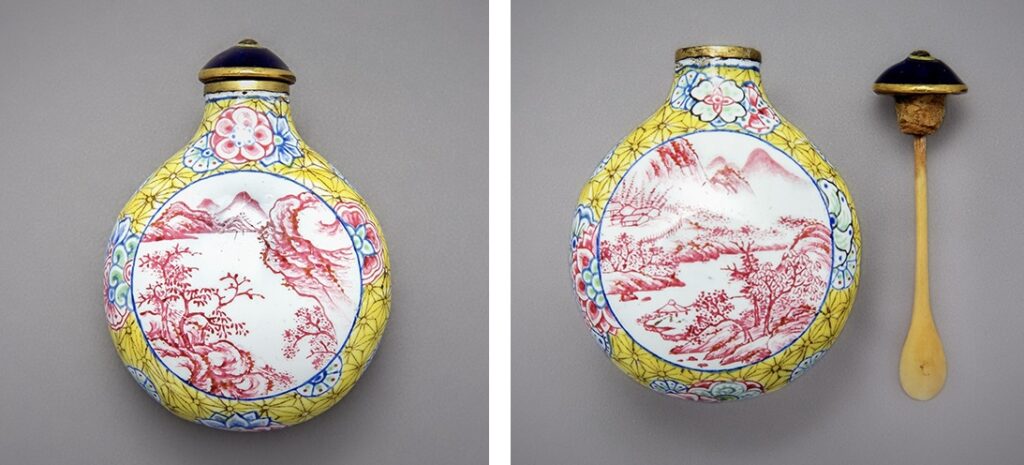

Between 1725 and 1733, Augustus II the Strong, Elector of Saxony (r. 1694-1733) and King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (r. 1697-1706, 1709-33), acquired an extraordinarily rare Chinese treasure for his Green Vault (Grünes Gewölbe). In 1723, this private Dresden palace royal treasury, originally known as the Privy Repository (Geheime Verwahrung), became the publicly accessible “Green Vault” where jewels, enamels, ivories, amber, rock crystal, gold, silver, and more from the royal collection were displayed. The collection was first inventoried in 1725. Included in the 1733 second Green Vault inventory, conducted after Augustus II’s death earlier that year, is a listing for “a golden-yellow enameled snuff bottle shaped like a flask. On the stopper is a blue enameled lid with a yellow dot. The bottle is yellow on the sides, with colorful Japanese flowers, but the two white fields are painted with purple trees and landscapes.”[1] Still held today in the Grünes Gewölbe collection within the Dresden State Museums (SKD), this early eighteenth-century painted enamel metal snuff bottle (Figs. 1a and 1b) could only have been made in the Beijing imperial court enamel workshops late in the reign of China’s Kangxi emperor (r. 1661-1722).

Its absence from the 1725 first inventory and appearance in the 1733 inventory suggests that it arrived during the intervening years, but Dresden and Beijing did not have any direct contact. How could one of the Qing dynasty’s first imperial painted enamel metal snuff bottles, produced explicitly for the Kangxi emperor and rarely presented as gifts even to the highest officials, have arrived at the Dresden court? Ulrike Weinhold and Rainer G. Richter suggest that it was most likely a gift from Kangxi to representatives of either Pope Clement XI (elected 1700; died March 1721) or Tsar Peter I (r. 1682-1721 as tsar, r. 1721-25 as emperor), whose embassies overlapped in Beijing from late 1720 into early 1721.[2] I argue that its most likely journey from Beijing to Dresden was via St. Petersburg, offering a different orientation to the movement of goods that defined Sino-European contact during the early eighteenth century.

Although the Dresden bottle has no reign mark, I agree with Weinhold and Richter that it can be dated stylistically and technologically to the Kangxi reign thanks to its similarities with a bottle held in the former imperial collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Figs. 2a and 2b), and which is marked “made for the imperial use of the Kangxi emperor” (Kangxi yuzhi 康熙御製). Both the Dresden and Taipei bottles share the same unusually round (rather than flat) bottom, a blue-capped stopper dotted with yellow enamel, and the design of a white-ground roundel (here of butterflies) set against a yellow geometric-floral textile-type ground. This and similar patterns can be found on other Kangxi-period painted enamels on metal and porcelain. Weinhold and Richter compare this triangle-based pattern with the Japanese “hemp leaf” (asanoha) textile pattern, and others have compared such patterns to both European and historical Chinese brocade patterns, a range that demonstrates the difficulty of pinning down a precise connection in the case of such globally-minded works as eighteenth-century Qing imperial painted enamels.[3]

While the Taipei bottle’s textile pattern is painted in dark red and deep blue enamel, stereomicroscopic magnification has revealed that the Dresden bottle’s lines—approximately half a millimeter wide—were created by sprinkling very finely ground gold leaf onto the enamel, a technique not otherwise used in either European or early High Qing painted enamel decoration, but a distinctive component of Japanese black-and-gold lacquer decoration.[4] The Dresden bottle’s “colorful Japanese flowers” described in the 1733 Green Vaultinventory are a pattern most often referred to in modern Chinese as piqiuhua 皮球花 (“flower-ball pattern”), tuanhua 團花, or tuanjiehua 團結花 (both translatable as “circular flowers”).[5] The pattern of stylized, overlapping, asymmetrical, multicolored, geometric floral motifs originated in Japan not only in relation to mon, family and institutional iconographic crests or emblems, as Weinhold and Richter argue, but also as simplified circular flowers and floral roundels used on Japanese ceramics, textiles, lacquerwares, and other decorative arts. These patterns can also be found on early seventeenth-century Chinese export porcelains intended for Japanese audiences, on late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Chinese porcelains produced in Japanese Imari styles, and even on other Kangxi-period painted enamelwares, demonstrating a persistent connection between this pattern and the Japanese archipelago before and during Kangxi’s time on the throne.[6] I have discussed elsewhere how Kangxi’s interests in Japan and Europe could be combined in painted enamels to triangulate a global Qing identity, specifically by incorporating insets of Japanese lacquer into painted enamel metal snuff bottles.[7]That the Green Vault inventory maker identified the colorful flower pattern as Japanese reveals not only his ability to distinguish Chinese from Japanese decoration, but also a broader recognition in the Dresden palace that Chinese and Japanese patterns differed, a distinction that was inconsistently observed in European collection inventories.

Painted enamel snuff bottles of imperial quality were not available for sale in the early eighteenth century, and would not have been sold by the few Qing officials upon whom the emperor personally bestowed early imperial workshop painted enamels. Such restricted availability supports Weinhold’s and Richter’s suggestion that the snuff bottle was likely acquired from one of the diplomats accompanying official embassies to Beijing in the early 1720s. Kangxi included enameled snuff bottles among the gifts for both the Pope and the Tsar, as well as for their ambassadors and the Tsar’s four highest-ranking representatives.[8] The gifts to Clement XI, which traveled from China with papal legate Carlo Ambrogio Mezzabarba (who also carried Qing gifts for King João V of Portugal), were lost when Mezzabarba’s ship Rainha dos Anjos burned at Rio de Janeiro on 17 June 1722.[9] Consequently, I suspect that the Grünes Gewölbe bottle was one of those presented to Russian ambassador Lev Vasilyevich Izmailov and his four highest-ranking subordinates during the second official Petrine embassy to China of 1719-21.

Gift exchanges between Tsar Peter and Kangxi began with the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk, a peace settlement that established formal boundaries between Russia and China, and established the right for regular Russian trade caravans to travel overland to and from Beijing. Both Petrine embassies to China (1692-95 and 1719-21) returned with official gifts from the Kangxi emperor.[10] Although some were lost when fire destroyed the Russian Kunstkamera in 1747, Qing imperial gifts presented to both the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century embassies were documented in colored drawings completed 1736-39, and several were recently rediscovered in the Hermitage collections.[11] Diplomatic gift exchanges also supported the political relationship between Saxony and Russia, which was bolstered by the personal relationship that the Tsar and the Elector maintained through increasingly frequent and personal presents, such as Peter’s 1704 gift of Japanese samurai armor that reflected their shared interests in East Asia.[12] But the lack of documentation for a Petrine regifting of Qing imperial presents makes it most likely that the Dresden bottle originated among gifts to the Russian embassy delegates. Perhaps, knowing of Augustus II’s fascination with East Asia, one of them was induced to part with his snuff bottle after returning to St. Petersburg. Russia’s regular caravans to Beijing provided unique access to Chinese goods and offers an avenue for future exploration of how Eurasian overland trade might have connected Dresden with Beijing.

Kristina Kleutghen is the David W. Mesker Associate Professor of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis, MO

[1] “Ein golden emaillirt Taback-Dosgen als ein Fläschgen. An dem Stöpßelgen ist ein blau emaillirt Deckelgen mit einem gelben Puncktgen; Das Fläschgen ist an denen Seiten gelb, mit bundten Japanischen Blumen, die zwey weiße Felder aber sind mit Purpur gemahlten Bäumen und Landschafft,” no. 461 in Grünes Gewölbe Inventar Pretiosen-Zimmer 1733 (Inv. 32, p.709), cited in Ulrike Weinhold and Rainer G. Richter, “Eine Email-pretiose des Kaisers von China in der Dresdener Schatzkammer?,” Dresdener Kunstblätter 59, no. 2 (2015): 101, 108n3.

[2] Weinhold and Richter, “Email-pretiose,” 107.

[3] Weinhold and Richter, “Email-pretiose,” 107–8; Ching-fei Shih, “Wenhua jingji: chaoyue qiandai, pimei Xiyang de Kangxi chao Qinggong hua falang,” Minsu quyi 182, no. 12 (2013): 178–80; Ching-fei Shih, “Hua Falang: The Chinese Concept of Painted Enamels,” in The RA Collection of Chinese Enamelled Copper: A Collector’s Vision, ed. Luísa Vinhais and Jorge Welch (London: Jorge Welsh Research and Publishing, 2021), 51; Chui-ki Wan, “Song jin zhi xiang: shiba shiji Guangdong falang yu waixiao ci de bafang jinwen,” Taida Journal of Art History 48 (March 2020): 159–240.

[4] Weinhold and Richter, “Email-pretiose,” 105–6.

[5] Xiaodong Xu, “A Hexagonal Vase in Copper Enamel with Circular Flower Motifs,” in The Secret of Colours: Ceramics in China and Europe from the 18th Century to the Present, ed. Pauline d’Abrigeon (Milan: Five Continents Editions, 2022), 60–65; Yue Yuan, “Piqiuhua ciqi,” Shoucangjia, no. 01 (2018): 49–52; Long Cheng, “Yongzheng doucai piqiuhua wen gai,” Zijincheng, no. 06 (1987): 32-33+11.

[6] Seizō Hayashiya and Henry Trubner, eds., Chinese Ceramics from Japanese Collections: T’ang through Ming Dynasties (New York: Asia Society, 1977), 115, fig. 70.

[7] Kristina Kleutghen, “Triangulating a Global Qing: China, Japan, and Europe in a Snuff Bottle,” Journal of Early Modern History 29, no. 6 (December 2024): 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1163/15700658-bja10089.

[8] George Robert Loehr, “Missionary-Artists at the Manchu Court,” Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 34 (1962-1963): 56–57, 57n31-32; John Bell, Travels from St. Petersburg, in Russia, to Diverse Parts of Asia (Glasgow: Robert and Andrew Foulis, 1763), vol. 2:70; Matteo Ripa, Storia della fondazione della Congregazione e del Collegio de’ Cinesi, vol. 2 (Naples, 1832), 73. Writing about the Russian embassy, the Jesuit and court servitor Matteo Ripa (1682-1746) recorded that Kangxi “gave the Ambassador and his four officers an enameled snuffbox, made in his Imperial factory” (“e donò all’ Ambassiadore, et à suoi quattro uffiziali una tabacchiera smaltata, fatta nella sua fabbrica Imperiale”).

[9] Loehr, “Missionary Artists,” 57; Emily Byrne Curtis, “Aspects of a Multi-Faceted Process: The Circulation of Enamel Wares between the Vatican and Kangxi’s Court (1700-1722),” Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident 43 (January 2019): 54–55; Emily Byrne Curtis, “Foucquet’s List: Translation and Comments on the Color ‘Blue Sky After Rain,’” Journal of Glass Studies 41 (1999): 147–52.

[10] Emily Byrne Curtis, “Chinese Glass: ‘A Present to His Czarish Majesty,’” Journal of Glass Studies 51 (2009): 138–43; Tatiana B. Arapova, “Kitayskie izdeliya khudozhestvonnogo remesla v russkom interyere XVII – pervoy chetverti XVII vv. K istorii kulturnykh kontaktov Kitaya i Rossii v XVII-XVIII vv,” Труды Государственного Эрмитажа (Trudy Gosudarstvennogo Ėrmitazha) 27 (1989): 108–9, 112–14.

[11] Maria Menshikova, “On Certain Official Precious and Rare Gifts to the Russian Emperor Peter I from the Chinese Kangxi Emperor,” The Tretyakov Gallery Magazine, July 20, 2022, https://www.tretyakovgallerymagazine.com/node/8375; Maria Menshikova, Dikovinnyĭ i dorogoĭ Kitaĭ : znaniia o Vostoke (Exotic and Lavish China: Knowledge of the Orient) (Saint Petersburg: Izdatelʹstvo Gosudarstvennogo Ėrmitazha, 2022); Maria Menshikova, “Chinese and Oriental Objects,” in The Paper Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, c. 1725-1760, ed. Renée. Kistemaker (Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2005), 247–69.

[12] Lydia Liackhova, “In a Porcelain Mirror: Reflections of Russia from Peter I to Empress Elizabeth,” in Fragile Diplomacy: Meissen Porcelain for European Courts, ca. 1710-1763, ed. Maureen Cassidy-Geiger (New York: Bard Center for Graduate Studies, 2007), 63–69; Werner Schmidt and Dirk Syndram, eds., Unter einer Krone: Kunst und Kultur der sächsisch-polnischen Union (Leipzig: Edition Leipzig, 1997), 257–59.

Cite this note as: Kristina Kleutghen, “Beijing to Dresden via St. Petersburg: An Early Qing Enameled Snuff Bottle in the Collection of Augustus II the Strong” Journal18 (February 2025), https://www.journal18.org/7657.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.