Jacqueline Riding, Basic Instincts: Love, Passion, and Violence in the Art of Joseph Highmore (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2017), 128 pages.

At every turn, contingencies pervaded London’s Foundling Hospital. Dedicated to “the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children,” the institution was, after years of debates, granted a Royal Charter in 1739. The first babies were admitted in 1741, and work began on Theodore Jacobsen’s grand building the following year (Fig. 1), with the Governors’ Court Room completed by 1745. Along with the customary web of historical forces required to create such an organization (in this case: the keen desire of a wealthy ship captain, Thomas Coram, to fund the project; moral arguments regarding charity and children born to unwed mothers; and Enlightenment ideals of improvement), any number of “what-ifs” dominated people’s lived experience with the Foundling. “What if she hadn’t been assaulted, coerced, or otherwise manipulated?” “What if she hadn’t gotten pregnant?” “What if she hadn’t won the lottery required for a baby to be received as a foundling?” And—as underscored in a poignant exhibition from the Foundling archive—“what if she had later returned to claim her daughter or son with the identifying token of affection, often a small scrap of fabric?”[1] Such acutely personal questions were echoed more broadly in larger public discussions regarding the intersection of public health, the public good, and the arts.

Fig. 1. Charles Grignion and Michael “Angelo” Rooker, after Samuel Wale, A Perspective View of the Foundling Hospital with Emblematic Figures, 1749. Etching and line engraving on moderately thick, moderately textured, beige laid paper, pasted on mount, plate 29 x 44 cm. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1978.43.1112.

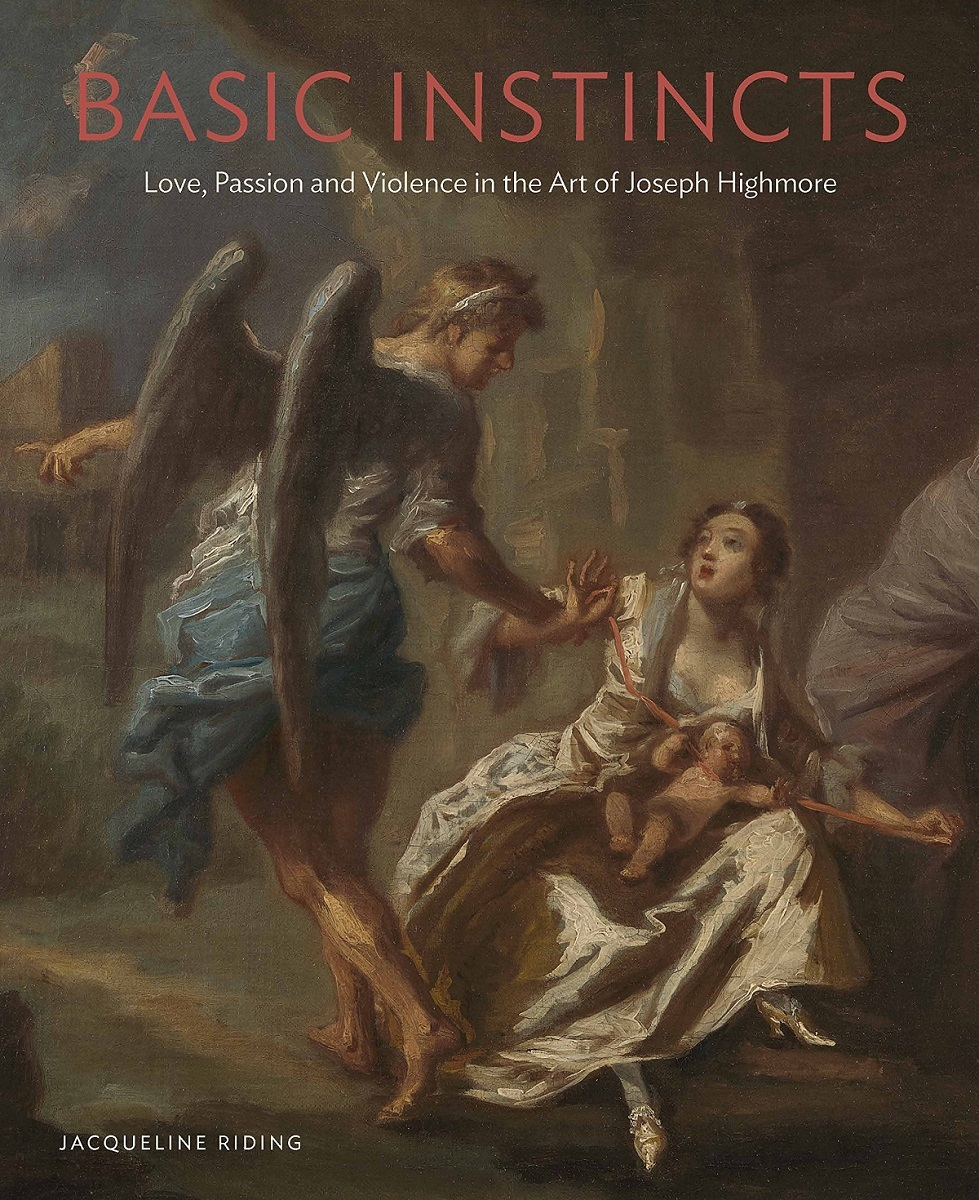

Joseph Highmore’s The Angel of Mercy (Fig. 2) is similarly characterized by a history of contingencies. Originally painted, or at least begun, for the Foundling (it is, in fact, unfinished), the picture never became part of its collection. Indeed, the current exhibition at the Foundling Museum, Basic Instincts: Love, Passion, and Violence in the Art of Joseph Highmore (on display from 29 September 2017 until 7 January 2018), marks the first time the painting has ever been publically displayed in the United Kingdom. A depiction of a mother dramatically interrupted from strangling her baby with a red cord through the intervention of an angel, the painting works to reframe one set of contingencies in terms of divine providence. In 1816, the then owner of the work, James Caulfield, offered the painting, which he attributed to William Hogarth, to the Foundling Hospital for 80 guineas, on the grounds that the picture was at least originally intended for the institution. While we have no response to his letter, the plan clearly went nowhere. In 1967, Colnaghi purchased the painting at Christie’s, selling it soon afterward to Paul Mellon, from whom it entered the collection of the Yale Center for British Art. After two centuries of the picture being incorrectly associated with Hogarth, Brian Allen first proposed Joseph Highmore as the painter, and recent work has borne out the attribution.[2] In a broad sense, Jacqueline Riding has been at work on the project, which now comes to fruition through the exhibition and accompanying publication, for the past twenty-five years. Riding wrote an MA thesis on the artistic career of Highmore’s daughter Susanna Duncombe at the University of London in 1994, and more recently completed a PhD on Joseph Highmore at the University of York in 2012.[3]

Fig. 2. Joseph Highmore, The Angel of Mercy, c. 1746. Oil on canvas, 59.7 x 48.3 cm. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.362.

As Riding observes in her book, Hogarth’s eclipse of Highmore led to general confusion around the latter’s artistic output, with works now seen as Highmore’s most accomplished pieces routinely assigned to his more famous contemporary, including Mr. Oldham and His Guests, now in Tate Britain. Things began to change in 1963 when forty-two paintings by Highmore were exhibited at Kenwood House, though the current exhibition at the Foundling is only the second serious monographic approach to the artist.[4]

In a remarkable reversal, The Angel of Mercy now finds itself in unprecedented demand. The painting was included in the exhibition Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the Shaping of the Modern World, as the show was installed in New Haven at the Yale Center for British Art in spring 2017. It likely would have also been on display at Kensington Palace for the installation of the Enlightened Princesses exhibition there this fall, were it not the centerpiece, across town, of the Foundling’s Basic Instincts show.[5]

The exhibition’s title, as Riding explains in the foreword, is intended to evoke the range of charged issues that led to the creation of The Angel of Mercy: issues “such as the status and care of women and children, master/servant relations, motherhood, reputation, abuse, abandonment, infant death and new-born child murder. Inseparable from these themes are the gamut of basic human instincts, or impulses, from love—whether romantic, familial, parental or fraternal—passion, compassion and humanity, to egotism, cruelty, fear and violence.”[6]

While the book accompanies the exhibition, it is not a catalogue, and perhaps most curious of all, The Angel of Mercy is in some ways a supporting rather than a leading character, at least to judge from the actual attention given to the painting. It is discussed for no more than seven pages. And yet, in another light, the book is a brilliant explication of the painting, precisely what readers need to understand in order to grasp this extraordinary picture.

Fig. 3. Joseph Highmore, The Vigor Family, 1744. Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 99.1 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax and allocated to the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2009, E.285-2009. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Five chapters address Highmore’s reception as an artist; his training among the circle of James Thornhill and the St Martin’s Lane Academy; his work as a painter of group portraits, including The Family of Sir Eldred Lancelot Lee (1736) and The Vigor Family (1744) (Fig. 3); his series based upon Samuel Richardson’s novel Pamela, consisting of twelve paintings, which had, by 1745, been engraved for the print market; and finally, his work for the Foundling Hospital, including not only The Angel of Mercy but also Hagar and Ishmael (1746), the latter of which was installed in the Governors’ Court Room alongside paintings by Hogarth, James Wills, and Francis Hayman.

All of the chapters have their pleasures, and this is a deeply satisfying book at many levels. It is a model for rethinking what a traditional monographic approach might look like within our own moment of art historical scholarship and publishing. By the conclusion—which isn’t especially difficult to reach even in a single setting—most readers will have learned something more about the world of painting in London from the 1720s to the 1740s, and a lot more about an artist who is only now receiving his due. Riding’s treatment of the prints for Pamela is masterful, as she manages to enliven material that could (for this reviewer at least) have been deadly tedious. Finally, and this is no small matter, Riding offers a compelling account of a “unified and dominant narrative,”[7] uniting the four paintings in the Governors’ Court Room into a coherent, collective scheme. Her proposal deserves serious engagement, but here I simply aim to highlight it in hopes of whetting readers’ interests.

With all of this material in place, Riding finally turns her attention to The Angel of Mercy directly in the closing pages, and this singular painting now seems less like an affront and more like a remarkably daring experiment. Riding cleverly brings the painting into conversation with Highmore’s Hagar and Ishmael and with larger conceptions of virtue, providence, and divine deliverance. The invocation of Abraham (Ishmael’s father in the Genesis account) might also open up another reading, which Riding doesn’t pursue: we might, I would suggest, think of The Angel of Mercy as re-casting (and re-gendering) the story of Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac. If the mother within the painting hardly emerges with the sort of heroic standing as the patriarch, her uneasy position corresponds all too truthfully to the ambiguous position of real-life mothers, who turned over their children to the Foundling Hospital. Staging that ambiguity in terms of an allegorical history painting that intersected with contemporary Georgian life was no small feat, and in the end, it didn’t find a home at the Foundling. There is something gratifying in knowing that, for at least a few months, it finally has.

Craig Ashley Hanson is Associate Professor of Art History at Calvin College, MI, and founding editor of Enfilade

[1] John Styles, Threads of Feeling: The London Foundling Hospital’s Textile Tokens, 1740–1770 (London: The Foundling Museum, 2010).

[2] Brian Allen’s suggestion is noted in Basic Instincts, 6.

[3] Jacqueline Riding, “Susanna Duncombe: A Quintessential Female Artist in Eighteenth-Century England?” (MA Thesis, University of London, 1994); Riding, “Joseph Highmore (1692–1780),” 2 volumes (PhD dissertation, University of York, 2012). See also Riding, “‘The Mere Relation of the Sufferings of Others’: Highmore, History Painting, and the Foundling Hospital,” Art History 35 (June 2012), 522–553.

[4] Elizabeth Johnston, Paintings by Joseph Highmore (1692–1780), exhibition catalogue (London: London County Council, 1963).

[5] Joanna Marschner, ed., with David Bindman and Lisa Ford, Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the Shaping of the Modern World (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 2017).

[6] Basic Instincts, 7.

[7] Basic Instincts, 108.

Cite this note as: Craig Ashley Hanson, “Basic Instincts: A Review,” Journal18 (November 2017), https://www.journal18.org/2336

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.