Louise Voll Box

In 1922, the English writer George Somes Layard commented that: “A series of marks on a print is its diary: the fate and journey of many a masterpiece can be thereby traced until it finds at last its permanent home in the Museum.”[1] Layard succinctly foreshadowed what might now be described as the materiality, agency, and lives of these art works: their materials and production; and the markings, annotations, and signs of use that connect the human stories of artist, printmaker, print publisher, dealer, collector, and collecting institution.[2] The potency of these narratives is magnified when prints are considered not only as individual objects, but also within, and in concert with, extant print albums.

Before the second half of the eighteenth century, collectors most commonly stored and displayed their prints in albums: book-like volumes often housed as part of a library. Since then, changing institutional display and storage preferences have resulted in the now customary presentation of prints in individual sunk or recessed mounts, rather than bound en masse.[3] As a result, intact albums of prints (especially those preserved in the arrangements determined by eighteenth-century collectors) are rare survivors.

Much important data about the assembly of print collections in the eighteenth century—once evident in the physical characteristics of intact albums—is now diminished or lost. These physical characteristics are the primary focus of this investigation. Adhesions, foliation, annotations, bindings, and signs of use (which are often overlooked by viewers or consciously excised from eighteenth-century print albums in institutional collections) can be as intriguing as the prints contained within the albums. These material features are also marks of identity and agency: they reveal the “lives” of the albums and the hand of the collector.

Introducing the Northumberland Albums in Melbourne

Fig. 1. Richard Houston (after Joshua Reynolds), Elizabeth Countess of Northumberland, Baroness Percy, Lucy, Poynings, Fitzpain, Bryan, and Latimer, c. 1759. Mezzotint, 49.8 × 34.6 cm. 2015.0038, Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Image courtesy Baillieu Library Print Collection.

The Baillieu Library at the University of Melbourne, Australia, houses nine folio-sized albums of prints—fortunately preserved essentially intact—that once formed part of the extensive collection of English aristocrat, Elizabeth Seymour Percy (1716-1776) (1st Duchess of Northumberland from 1766) (Fig. 1). The Duchess and her husband Sir Hugh Smithson, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1712-1786), were active arts patrons, and the Duchess was an eager collector of pictures, prints, medals, coins, cameos, busts, minerals, and curiosities, many acquired during her frequent travels.[4]

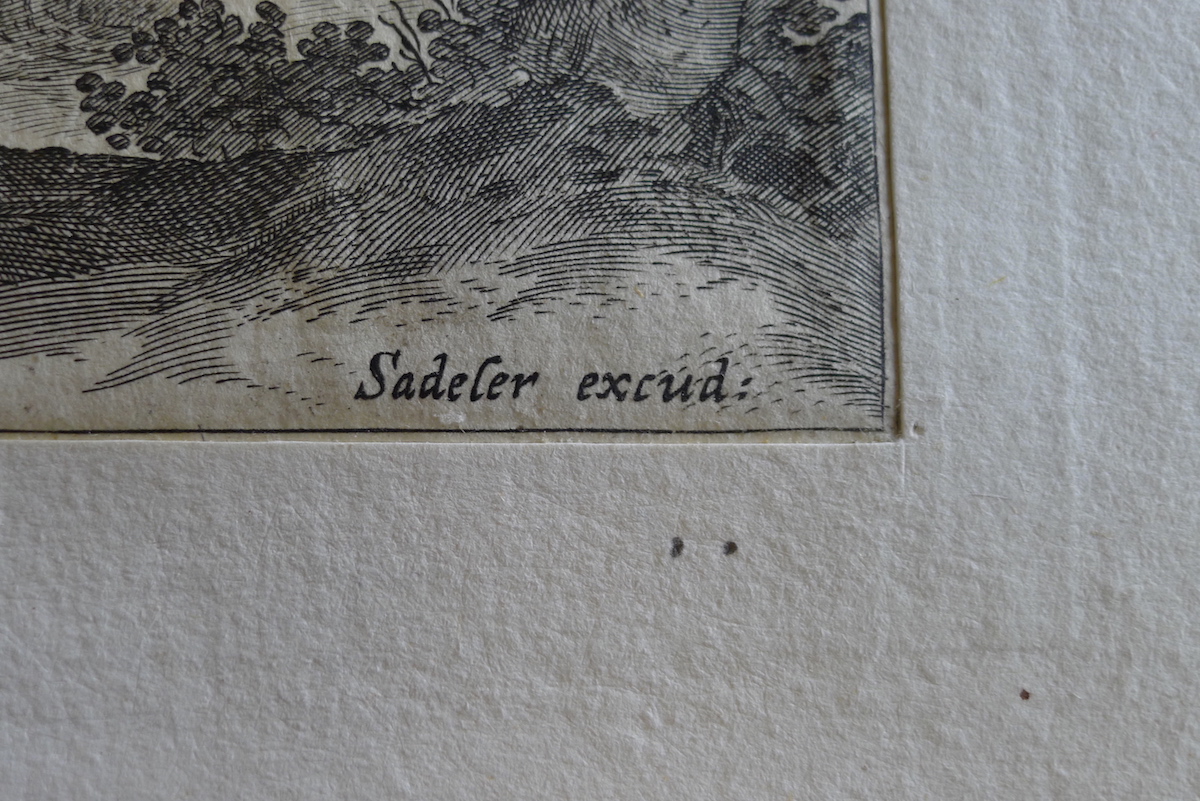

The nine Northumberland albums in Melbourne predominantly contain impressions by two generations of the Sadeler family, prominent sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Flemish print makers/publishers.[5] Purchased by the University of Melbourne from the London print dealer Colnaghi in 1962, the albums fall into two categories.[6] The first group are seven albums acquired by the Duchess in the 1740s, when the extensive collections of the 1st and 2nd Earls of Oxford, Robert Harley (1661-1724) and his son Edward (1689-1741), were auctioned in London by Thomas Osborne and Christopher Cock.[7] These albums with Oxford provenance (subsequently referred to as the “Oxford” albums) will only be briefly addressed here. The other two albums (hereafter the “De Vos” albums) are the primary focus of this discussion, and feature prints by the Sadeler family after Maarten de Vos (1532-1603).[8] Not only were prints in the De Vos albums arranged by the Duchess using an unusual mounting technique,[9] they also contain annotations in her own handwriting which have not been described in previous research.[10] Analyzing these annotations, and the physical features of the prints and albums, allows us to follow the sequential development and arrangement of the Duchess’s print collection.

The Duchess’ annotations, the unusual mounts, and the presence of many surviving loosely-interleaved, partially-cut prints suggest that the two De Vos albums have been intriguingly caught-in-process only part-way through their assembly. Other evidence—such as their bindings, paper stock, and the palimpsest of adhesions, markings, and foliation—maps the trajectory of the albums’ collation, storage, and provenance. Most significantly, as will be explored here, the De Vos albums’ rich physical features elucidate new information about the albums’ method of assembly, and the intentions of the collector at the moment of making. Investigation of the materiality of the De Vos albums also clearly demonstrates that these print albums and the prints within them were not a static form in the eighteenth-century, but were constantly in flux.

The Duchess and the De Vos Albums

Many of the Duchess’ diaries, travel journals, hand-written collection inventories, and notes about the development of her collection survive in the Archives of the Duke of Northumberland at Alnwick Castle, Northumberland.[11] A number of these documents refer to the print albums now in Melbourne. The depth of this supporting material is in stark contrast to the information available about other English eighteenth-century print albums. For example, although 198 albums (over 40,000 prints) collected by Richard, 7th Viscount Fitzwilliam (1745-1816) are held at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, very few documents, apart from the prints themselves, remain to shed light on his collecting practices.[12] As described by Marjorie B. Cohn, “only rarely has [a print] collection, together with its original catalogue, survived to speak for itself.”[13]

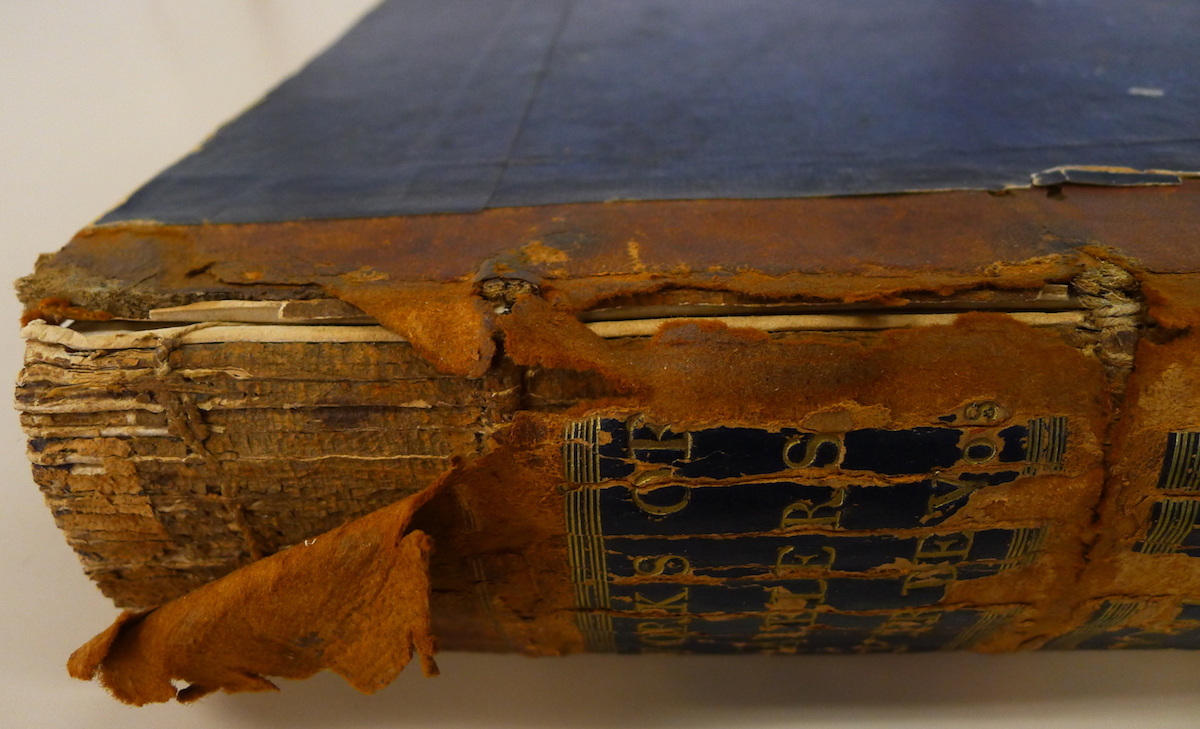

Fig. 2. Album binding and spine (detail) of one of the Oxford Albums. UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37BB/2 v.8 Mark and George. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

Analyzed together, archival sources and the physical features of the Melbourne Northumberland albums present new narratives about the collation and assembly of the Duchess’ print collection. The Duchess recorded her varied collections in a carefully handwritten, specially-bound, eight-volume inventory, her Musaeum Catalogue, which includes a volume titled Catalogue of Prints.[14] The Catalogue of Prints is indexed into a series of high-level categories, opening with a listing of “Books of Prints”, followed by subjects (e.g. “Natural History”, “Sacred Subjects”, “Portraits”), then printmakers/designers (e.g. “Works of Sadeler”, “Works of Devos”).[15] Prints are then listed as sets or volumes rather than individually. Entries record the subject, printmaker, the number of prints and their price, and occasionally note their provenance. Under “Works of Sadeler”, the Duchess lists over 3800 prints in her collection.[16] For example, the seven Oxford-provenance albums in Melbourne are described in the Duchess’ Catalogue as “Bought out of Lord Oxford’s collection,”[17] and in another notebook as “Collection of Sadelers bought at Osbornes.”[18]

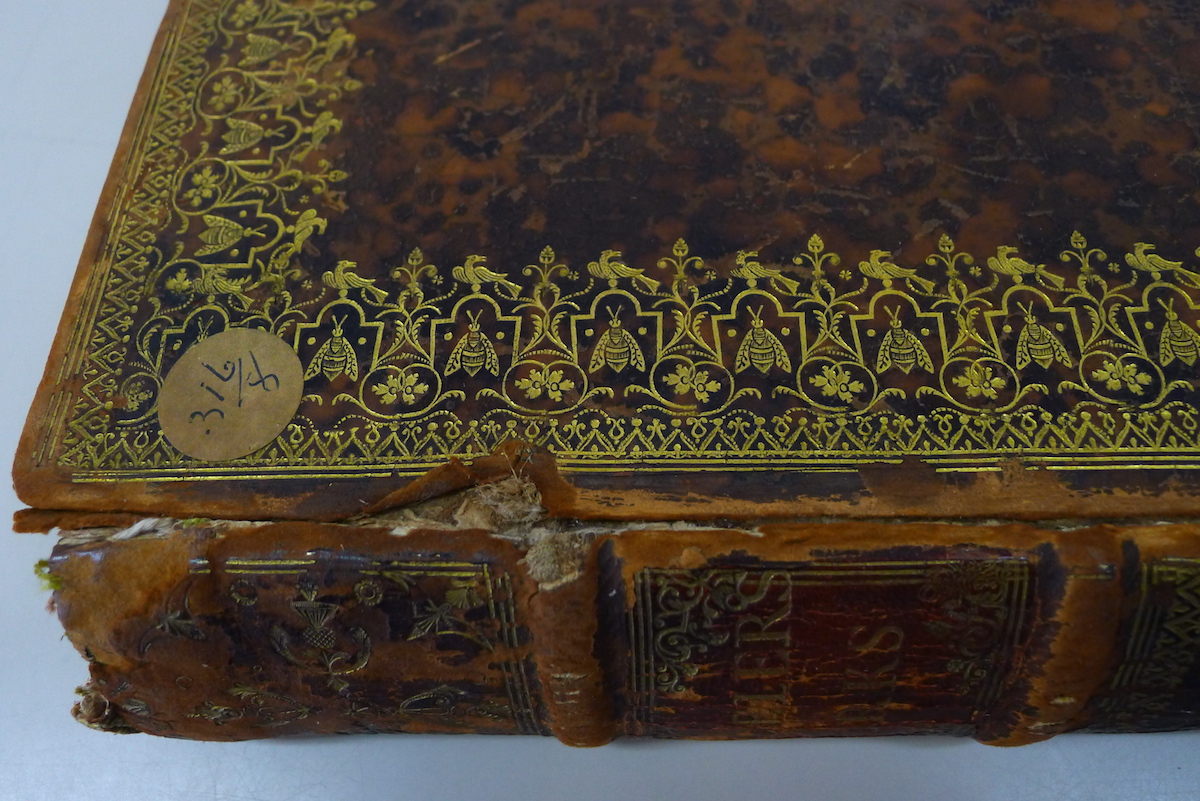

Fig. 3. Album binding and spine (detail) of one of the De Vos Albums. UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

The Duchess made an unusually specific note about the De Vos albums in her Catalogue of Prints. They are recorded (under the list for “Works of Sadeler”) as “Volume[s] [ar]ranged by myself, de Vos.”[19] This intriguingly self-referential entry foregrounds the collector’s relationship with this particular group of works: she took pride in arranging these albums. Despite this, both De Vos albums contain prints in poorer physical condition and of lower quality than those in the seven Oxford albums. The latter are ornately bound in full morocco in “Harleian” style with gilt-edged leaves and gold-tooled covers and spines (Fig. 2).[20] In comparison, the De Vos albums are only half bound in leather, with unadorned blue boards, and with a lower-quality paper stock that is typical of modest eighteenth-century binding (Fig. 3). Despite their unprepossessing exteriors, the De Vos albums had special significance for the Duchess.

“Amateur Handiwork”: The Tabbed Print Mounts in the De Vos Albums

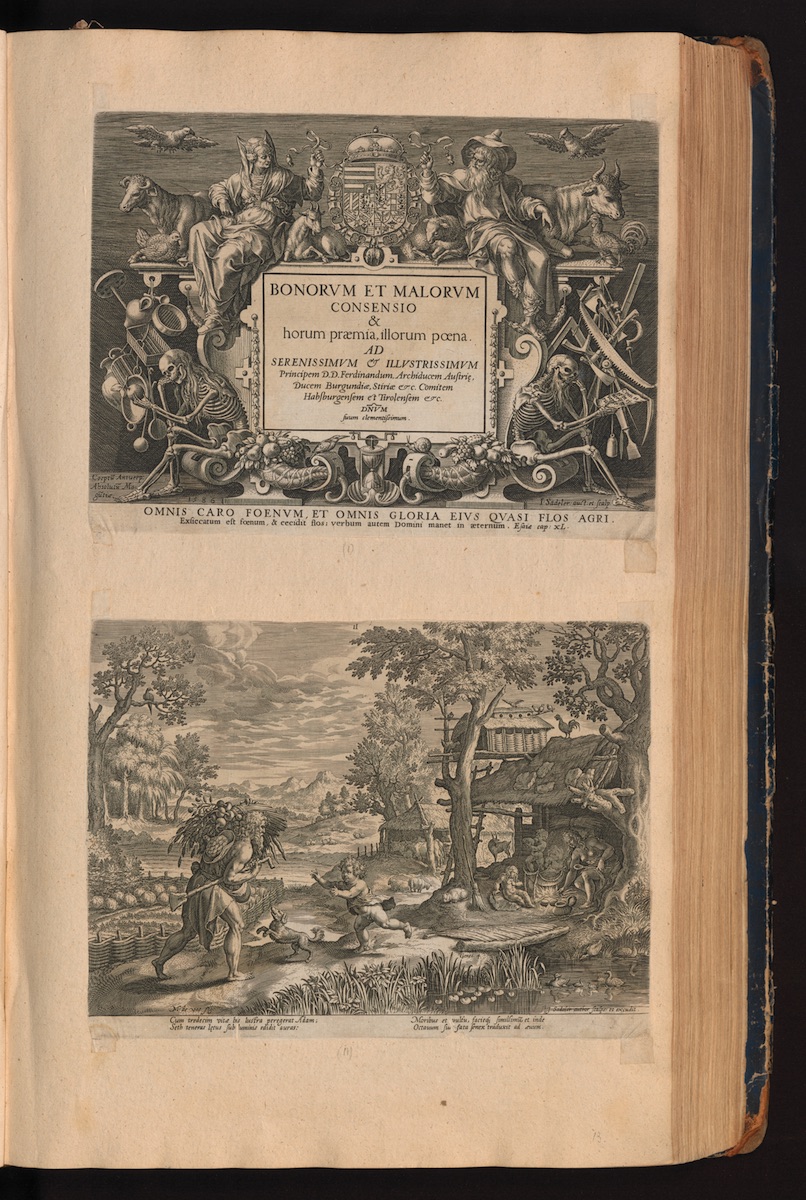

Fig. 4. Examples of tabbed prints. Johannes Sadler I (after Maarten de Vos), Titlepage from The Story of the Family of Seth, 1586, engraving, 20.3 x 27.5 cm; and Adam with Seth and Family, engraving, 20.3 x 27.5 cm. UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/2 v.1A Sadelers/de Vos, f.13. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Image courtesy Baillieu Library Print Collection.

The hand of the collector is richly evident in the De Vos albums. Similar to some other surviving albums from the Duchess’ collection, these albums feature an unusual tabbed print adhesion system. Antony Griffiths described the tabs as the Duchess’ “amateur handiwork” and as “a peculiar characteristic that I had (and have still) never seen elsewhere.”[21] Conventionally, amateur eighteenth-century English print collectors mounted prints in albums using folded hinges, or adhered the prints with glue in the corners, or glued the entire verso of each print to the album leaf.[22] The prints in the De Vos albums, however, are pasted onto album leaves using four rectangular-shaped tabs of unfolded paper, cut—in many cases—from the margins of each print. The rest of the print margin has been removed. Only the tab is then used to adhere the print to the album leaf, leaving the body of the print un-adhered (Fig. 4).

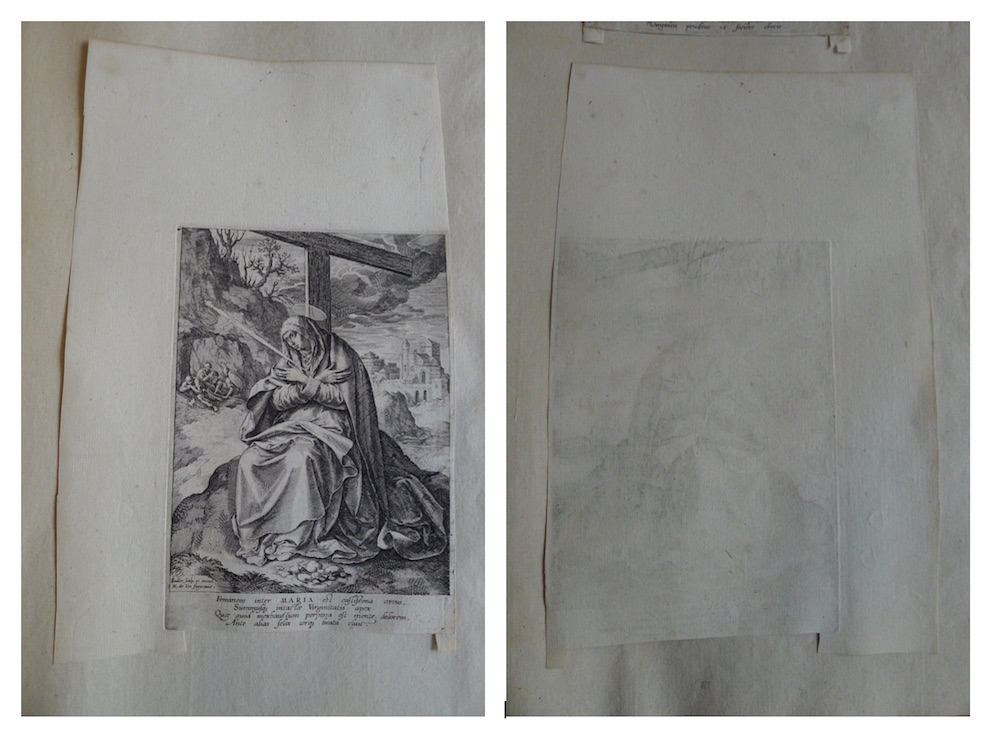

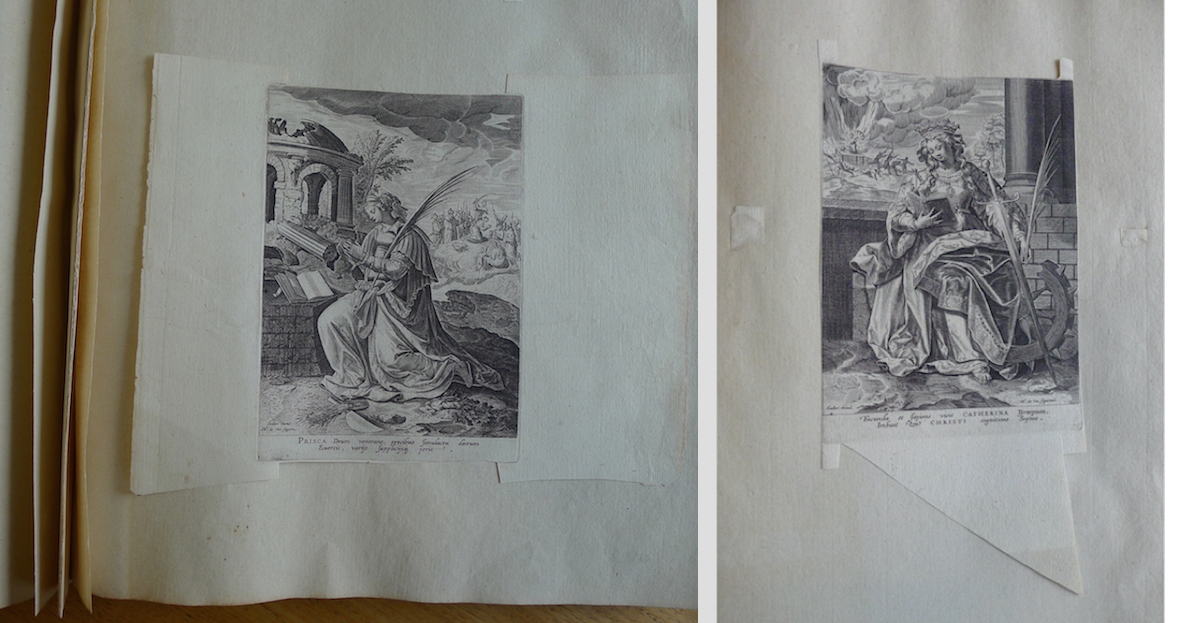

LEFT: Fig. 5. Loose print showing margins partially cut into tabs. Johannes Sadeler I (after Maarten de Vos), Mater Dolorosa, 1584-1587, engraving, 18.4 x 12.9cm (image only). UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos, f.91a. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

RIGHT: Fig. 6. Loose print showing margins partially cut into tabs (verso): Johannes Sadeler I (after Maarten de Vos), Mater Dolorosa, 1584-1587, engraving, UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos, f.91a Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

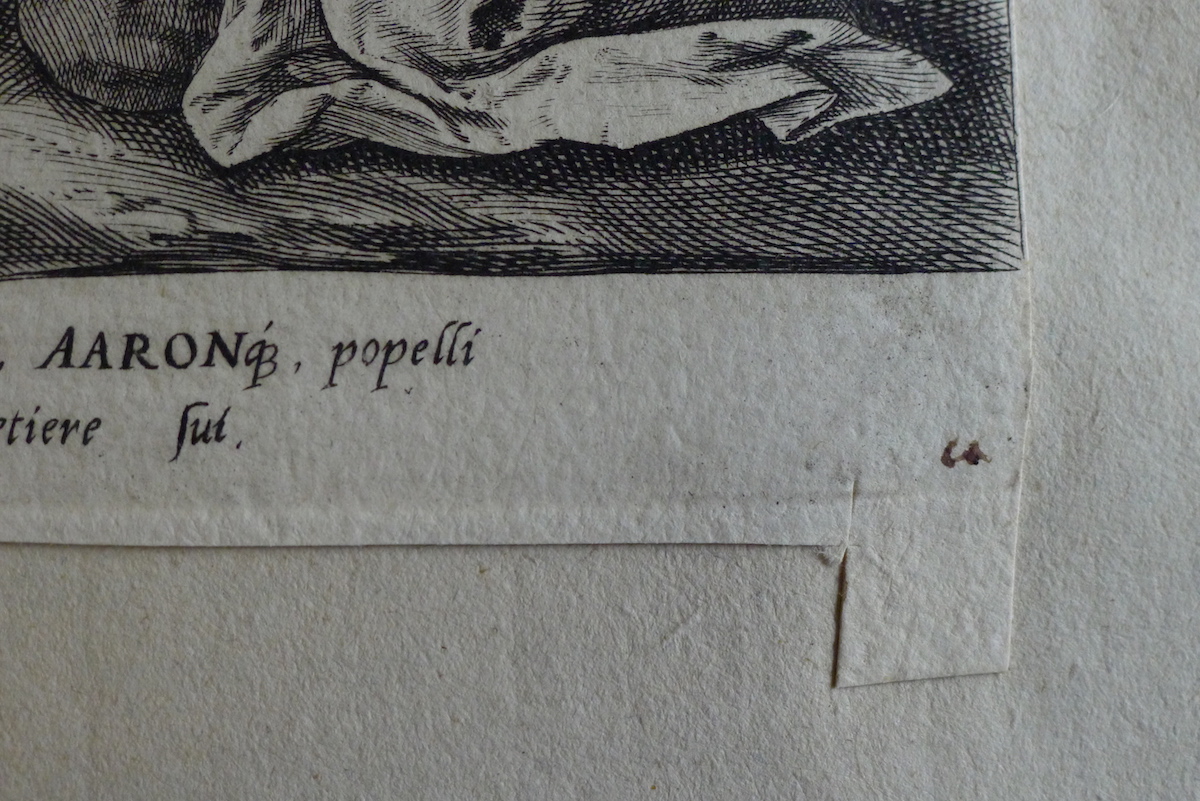

A number of prints still loose in the leaves of the De Vos albums are partially cut into tabbed shapes, and demonstrate the unusual cutting procedure “in process”. Most striking of these astonishing survivals are several prints from the Speculum Pudicitiae (Mirror of Chastity) series (Fig. 5).[23] Two sides of the print Mater Dolorosa retain full margins, and the other two margins have been cut into tabs (Fig. 6).[24] The margins of St Prisca have also been partially cut, and the format of the print’s left edge demonstrates that it has been removed from an earlier binding (Fig. 7).[25] Only one final margin of St Catharina requires cutting into the tab form (Fig. 8).[26]

LEFT: Fig. 7. Loose print showing margins partially cut into tabs. Johannes Sadeler I (after Maarten de Vos), St Prisca, 1584-1587, engraving, 18.4 x 12.8 cm (image only). UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos, f.100. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

RIGHT: Fig. 8. Loose print showing margins partially cut into tabs, and remnants of other tabs still adhered to the album leaf. Johannes Sadeler I (after Maarten de Vos), St Catharina, 1584-1587, engraving, 18.2 x 12.9cm (image only). UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos, f.95a. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

These crudely-cut tabs are the antithesis of eighteenth-century luxury print mounting techniques. Prints in the Oxford albums in Melbourne are encapsulated between two layers of heavy paper stock, a process usually completed by specialists (Fig. 9). Elaborate, decorative techniques were used by French dealer and collector Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774), whose skillfully-executed mounts were often embellished with gold borders and elaborate cartouches that were designed to enhance the visual sophistication of each print.[27] Elite eighteenth-century collectors such as Prince Eugene of Savoy and the Duc de Mortemart engaged Mariette’s firm to mount (and often acquire) their print collections.[28] The Duchess certainly had the financial means to commission professionals to present her print collection, and she was familiar with a cross-section of print dealers, booksellers and binding specialists across Europe.[29] Nevertheless, prints in the De Vos albums are adhered using roughly-cut, irregularly sized and shaped tabs.[30]

Fig. 9. Encapsulated mount (detail) from UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37BB/2 v.8 Mark and George. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

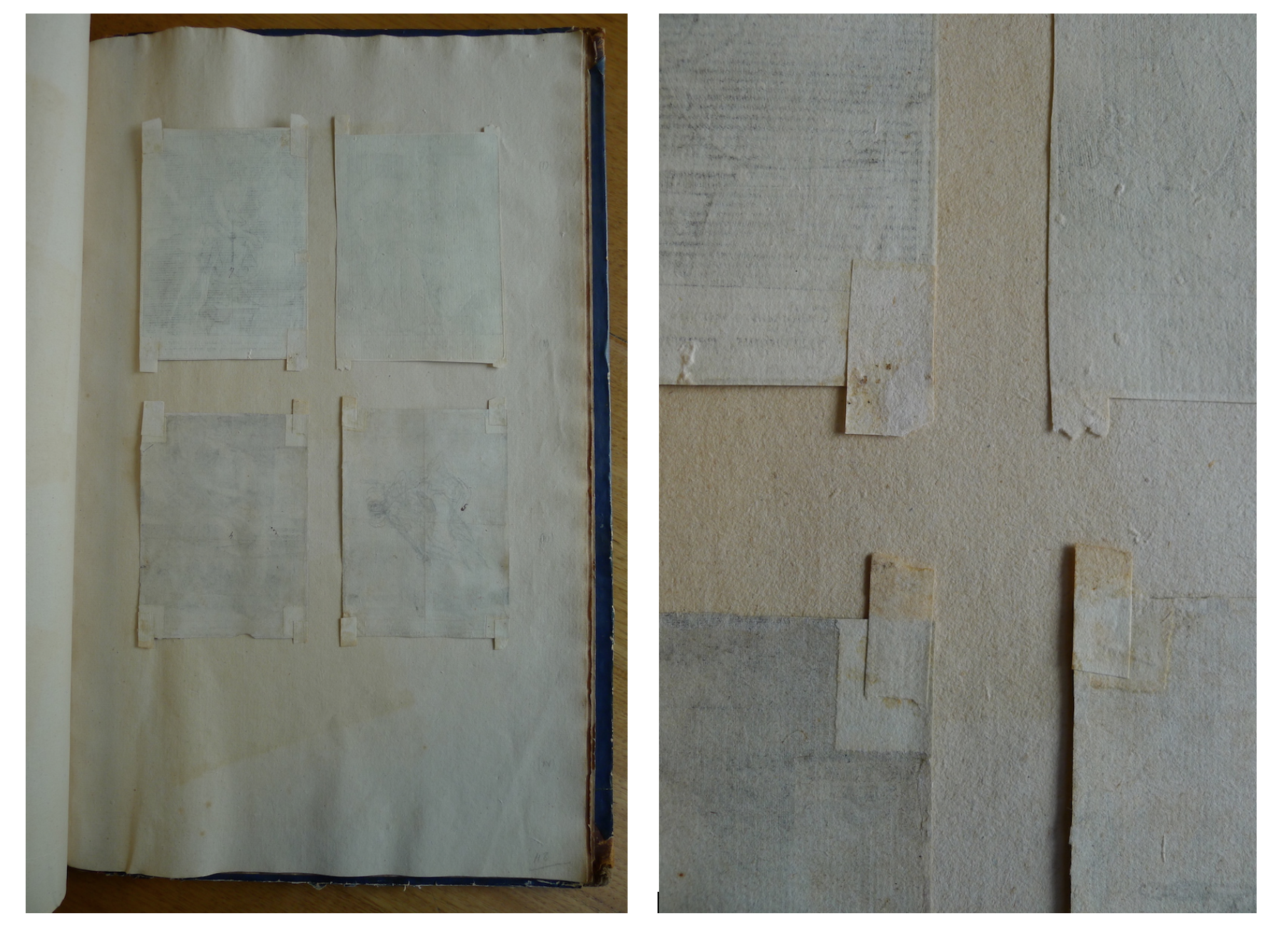

Physical evidence suggests that the tabs were an important design feature. The use and re-use of the tabbed mounting technique can be observed through the remnants of earlier tabs, which are still adhered to many De Vos album leaves. Layers of tabs and repairs are visible on the versos of several unmounted prints (Figs. 10 and 11). But the question remains as to why this hand-made technique would feature so prominently.

LEFT: Fig. 10. Layering of tabs and repairs on the versos of prints. Johannes Sadeler I (after Maarten de Vos), selection from The Seven Liberal Arts, after 1575, engravings, each approx. 14.8 x 10.9 cm. UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos, f.118. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

RIGHT: Fig. 11. Layering of tabs and repairs on the versos of prints. Detail of Fig. 10.

It is my contention that the tabs were intended for a practical purpose, rather than an aesthetic one: the ease of moving and re-arranging prints in the Duchess’ collection. Moreover, it is likely that the modestly-bound De Vos albums were temporary, “working” albums, where prints could be placed and re-ordered until the collection was considered complete, as will be further explored. Although we now consider albums as static or ‘complete’, in the eighteenth century they were constantly in flux. Collectors (and dealers) incorporated prints and album leaves from other collections into albums; prints were frequently lifted and replaced in a different order; and some collectors only assembled sheets of prints into finely-bound albums at the end of their collecting career, when no further additions were expected.[31]

A tabbed mounting system offered several advantages to collectors. The prints could be removed and re-arranged merely by slicing off the tabs; and because the prints are only adhered in their margins, they do not suffer from cockling (a problem when the whole surface of the print is adhered). Given that the Duchess acquired many of her prints from other collections through auctions and print sellers, it is possible that she personally experienced frustrations with print re-arrangement. After observing cockling as well as damaged and repaired corners of prints from other collections, it is likely she sought a solution that would overcome these common issues.[32]

Cutting and pasting of prints and paper was a popular creative pursuit for the upper echelons of European society in the eighteenth century, but it is currently unclear what inspired the Duchess to use the tabbed technique. Decoupage, paper collage, glass-transfer painting, grangerisation (the extra-illustration of books using prints), and embellishing fashion prints with textiles were all interrelated elite domestic activities.[33] The Duchess’ diaries, correspondence, and notebooks reveal little or no evidence of her interest in any of these variations of cutting and pasting prints.[34] Although the ingenious tabbed form does not immediately link with any of these other cutting activities, it may be seen as a response to the contemporary interest in the manipulation of prints and paper.

The arrangement and care of print collections was a hobby and a genteel, creative pursuit in the eighteenth century, and trimming prints was part of this interest.[35] Mariette records that the artist/collector Benedetto Luti (1666-1724) spent “a good part of his time…employed on cutting, pasting and tidying his drawings and prints,” and that he was always found “with a pair of scissors in his hand, ready to cut the edges off some print.”[36] This form of print cutting, however, usually entailed trimming off the margins of prints (to save space in albums) rather than cutting the margins into tabs. Whatever her inspiration and motivation,[37] the Duchess’ tabbed prints continue to be a unique and “peculiar characteristic” that has not been observed in other collections.[38]

Pasting is clearly mentioned in the Duchess’ notebooks. A helpful list titled “Prints pasted” records two albums of “Sadeler after de Vos,” almost certainly the two albums now in Melbourne.[39] Another notebook contains what appears to be a to-do list for [Jean] “Vilet”, a member of her household.[40] It includes an entry that reads, “my Bouchers to be pasted.”[41] Another entry records a 10s 6d payment to artist John Bell “for sorting prints”.[42] It is therefore unclear whether the Duchess arranged and cut and adhered her prints, or directed others to adhere them.[43] In any case, she was sufficiently satisfied to specifically and unusually record her involvement with “[ar]ranging” in her Catalogue of Prints.[44]

Fig. 12. Example of integrated tab (detail) from UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos, f. 47. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

Fig. 13. Example of supported tab (detail) from UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos, f. 66. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

Close study of the tabs also allows us to see another aspect of the Duchess’ collecting approach “in process”: her penchant for the sequential arrangement of each print in a particular series, and her gradual and systematic acquisition of missing prints. Three variations of the tabbed mounts can be observed in the De Vos albums, and I have categorized these into specific forms. Identifying these variations will assist in understanding the Duchess’ processes for print collation and album assembly. First, there are integrated tabs, where the margin of the print is cut into tabs as previously described (Fig. 12). Second, there are supported tabs, where the print is adhered to another support (perhaps the leaf from an earlier collectors’ album), and this support is then cut into tabs (Fig. 13). Finally, there are separate tabs, where small, rectangular pieces of paper (often from a completely different paper stock) are adhered to the verso of the print (Fig. 14). Some prints contain a combination of both integrated and separate tabs, the latter probably used if one margin was already trimmed close to the plate-mark. Irrespective of their construction method, only the tabs adhere the print to the album leaf, and their similar form visually connects each print. These variations of tabs become more important when considered in conjunction with annotations in the albums: the next stepping stone to understanding the albums as a process rather than a static production.

Fig. 14. Example of separate tab (detail) from UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/2 v.1A Sadelers/de Vos. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

Analyzing Annotations

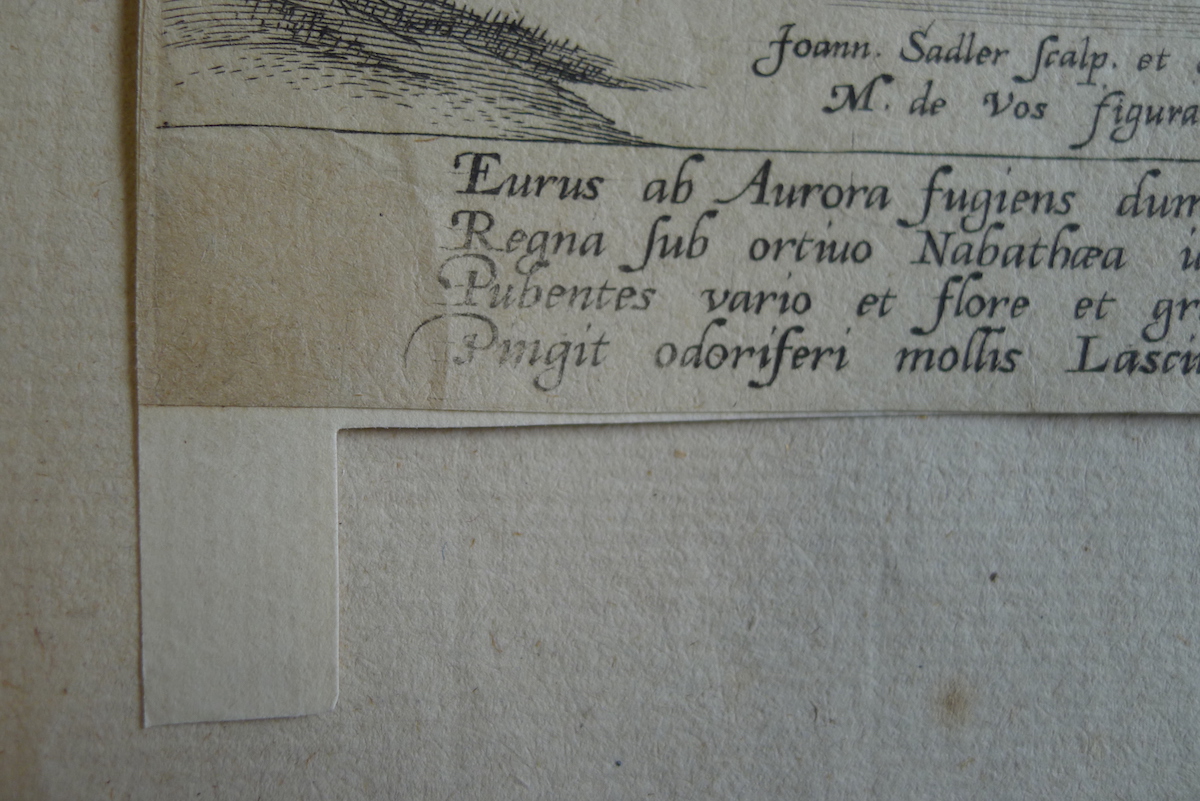

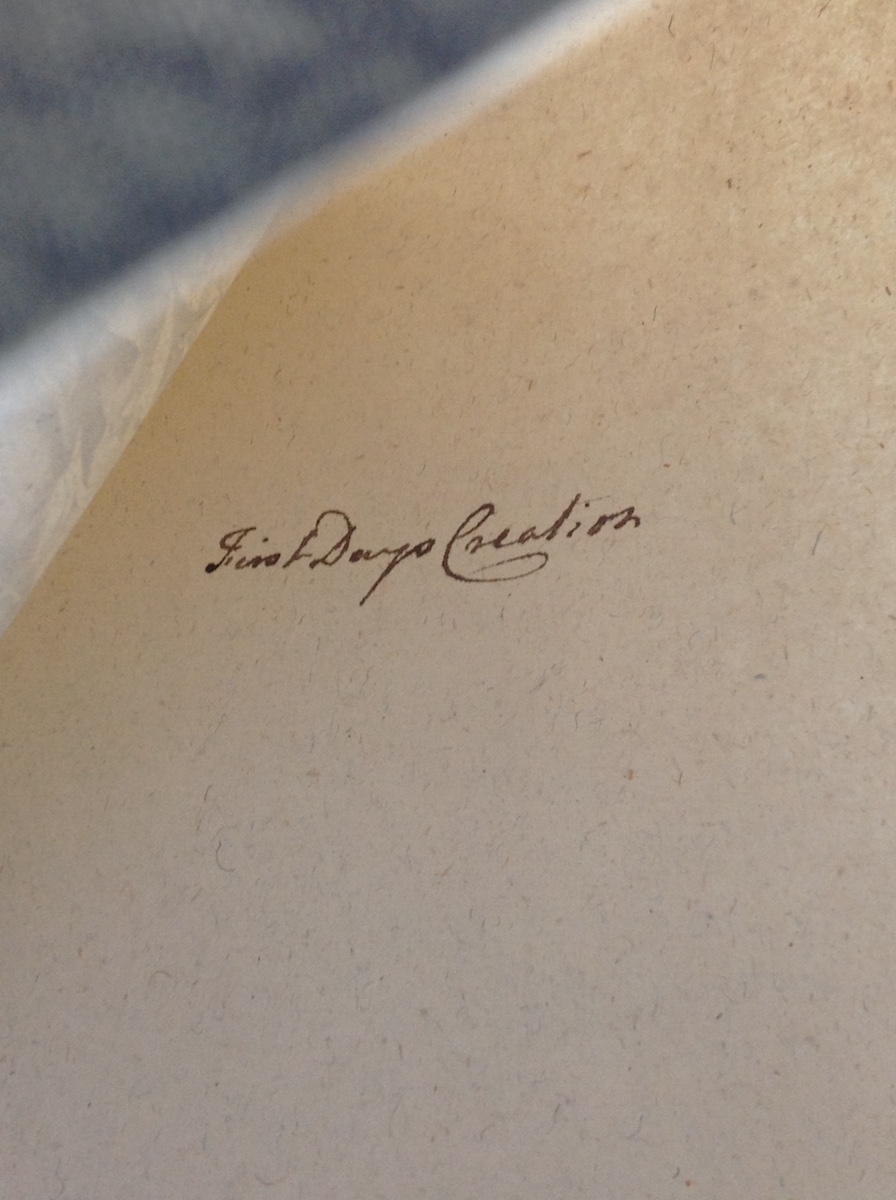

Hidden underneath prints in the De Vos albums, previously undescribed annotations provide new information about the Duchess’ focus on the sequence of her prints. De Vos album v.1A opens with the series Creation of the World by Johannes Sadeler I (published 1580-1590) and includes a title page and seven prints.[45] Fortuitously, some tabs on the prints are no longer adhered, allowing the album leaf below to be revealed. Beneath the print titled Creation of Light is an ink annotation that reads “First Days Creation” (Fig. 15).[46] The distinctive flourish of the “C” reveals the annotation is written in the Duchess’ handwriting. It appears she reserved spaces for prints and wrote the names of missing prints in the appropriate places on the album leaves. When acquired, the additional prints were adhered, thereby concealing the earlier annotations.

Fig. 15. Notation on album leaf under print by Johannes Sadeler I (after Maarten de Vos), The First Day: The Creation of Light, 1580-1590, engraving. UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/2 v.1A Sadelers/de Vos f.3. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

Other annotations are even more revealing. On the leaf behind the print of Cain Tilling the Ground, Abel as Shepherd, part of the series of Boni Et Mali Scientia (The Story of the First Men, 1583), the Duchess wrote in ink: “Cain ploughing Abel finding Thief / Genes is 4 No. 5.”[47] The spacing of her annotation as “Genes” confirms the Duchess was familiar with the second state of this series, which included the numeral “5” at the center bottom, and the word “Genes” (rather than “Genesis”).[48] This specific information was noted by the Duchess on the album leaf, ready for the appropriate impression to fill the space (either a print from her own collection, or one still to be acquired).

Detailed analysis of the annotations and the type of tabs reveals the Duchess’ collation of the albums over time, and suggests that prints were obtained from different sources. The case of The Seven Planets series by Johannes Sadeler I neatly demonstrates this approach.[49] Prints within the series fall into three subgroups, each of which have visually similar discoloration and/or marks of damage. This means there may be at least three different sources of prints that were mounted together to form The Seven Planets series. To assist our investigation, subgroups of similarly aged or damaged prints have been assigned a letter (A, B or C). For example, the title page of The Seven Planets and the prints Venus and Mars have visually similar characteristics, so have been notionally assigned to subgroup ‘B’. It is likely these prints were obtained from the same source at the same time.

By analyzing the tabbed structures of the prints and their proximate annotations, we can begin to understand the sequential placement of prints. The following table shows the relationships between annotations and the physical features of the prints (Table 1). From this information, for instance, we can deduce that the print Luna/The Moon must have been trimmed to the platemark at the time it was adhered in the album, thereby requiring separate tabs to be made. There are no concealed annotations, which indicates the print was available and could be immediately placed into the album. It is likely that Mars and Venus, (part of group B) were added to the album later. Both prints have integrated tabs and similar visual discoloration, and the annotations “Mars” and “Venus” are now concealed by the prints. We can therefore deduce that Mars and Venus were probably obtained from the same source and that both originally had margins which were cut into integrated tabs. Allocated spaces for Mars and Venus were noted by the annotations, and the prints were later positioned in the album, thereby concealing the annotations.

| Title | Tab style | Evidence of previous mounting | Concealed annotation | Assigned Print Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title page | Integrated | - | Planetarum Effectus | B |

| Saturnus | Separate | Yes | Saturn | A |

| Jupiter | Separate | Yes | - | A |

| Mars | Integrated | - | Mars | B |

| Sol/The Sun | Separate | Yes | - | A |

| Venus | Integrated | - | Venus | B |

| Luna/The Moon | Separate | Yes | - | C |

| Mercurius | Separate | Yes | - | A |

We can observe this process in action even when an album leaf contains only handwritten annotations, but no prints. For example, the inked words “Seeing”, “Hearing”, “Feeling”, “Smelling” and “Tasting” are most likely notes to allocate spaces for the future acquisition of The Five Senses series after De Vos by Raphael Sadeler I, circa 1581. [50] Annotations like these are valuable evidence indicating the intended future directions of the Duchess’ collecting.

The Evolution of a Print Collection

Analysis of the tabs and annotations suggests that the Duchess was following a specific collecting schema. As Beth Fowkes Tobin explains, the hallmarks of a “systemic collection” are objects, “arranged along some scheme that exists outside the individual collector’s mind.”[51] Annotations under prints in the De Vos albums clearly indicate the Duchess was familiar with the themes, specific lettering, and numerical sequence of the prints she desired, and that she had observed these features either in her own or other collections. She then used this knowledge to accurately position prints in their numerical order, and to mark specific spaces for future purchases. This was not as complex as it might first appear because many prints (particularly those of Flemish and Netherlandish origin, which were favored by the Duchess) were available in series or sets. Each print was numbered in sequence within the platemark to encourage collectors’ acquisition of the full set.[52] What is still to be determined is whether the Duchess’ preference for fastidiously following the numbers of each series is evidence of a sophisticated, overarching collecting approach, or just a simple and effective method of highlighting missing prints.[53] Either way, the Duchess’ collation of the De Vos albums was clearly systematic, as prints have been arranged in their correct series and in numerical order.[54]

Archival evidence also helps us follow the evolution of the Duchess’ print collection. Two lists in the Duchess’ hand document her active interest in recording information about prints after De Vos. A notebook at Alnwick Castle records over 45 sets of prints (over 650 individual prints) “Sent to Mr Darres.”[55] The list includes several series’ by the Sadeler family after De Vos which appear in the albums in Melbourne, including Boni et Mali scientia (The Story of the First Men), and Imago Bonitas illius (Creation of the World). William Darres was a fine-art auctioneer and print specialist in Coventry Street, London, active from 1749 to 1768, so it seems likely that the Duchess sent duplicate prints to be sold by his firm.[56] Another thin notebook is devoted entirely to prints after De Vos.[57] In it there are nearly sixty detailed entries recording sets and individual prints, a number of which are listed in the same order as the prints mounted in the two De Vos albums. In the absence of further evidence, it is not yet clear precisely what purpose this notebook served. It may have been an earlier and more detailed preparatory document for the Duchess’ Catalogue of Prints; a list of prints already acquired; a list of prints to be obtained; or a list of prints to be (or that have been) mounted in albums. In any case, these documents demonstrate a fastidious recording of this part of her collection. No other similarly detailed lists of prints in the Duchess’ hand (for any other printmaker or artist), have been located to-date.

Assembling and Storing the De Vos Albums: Binding, Foliation and Paper Stock

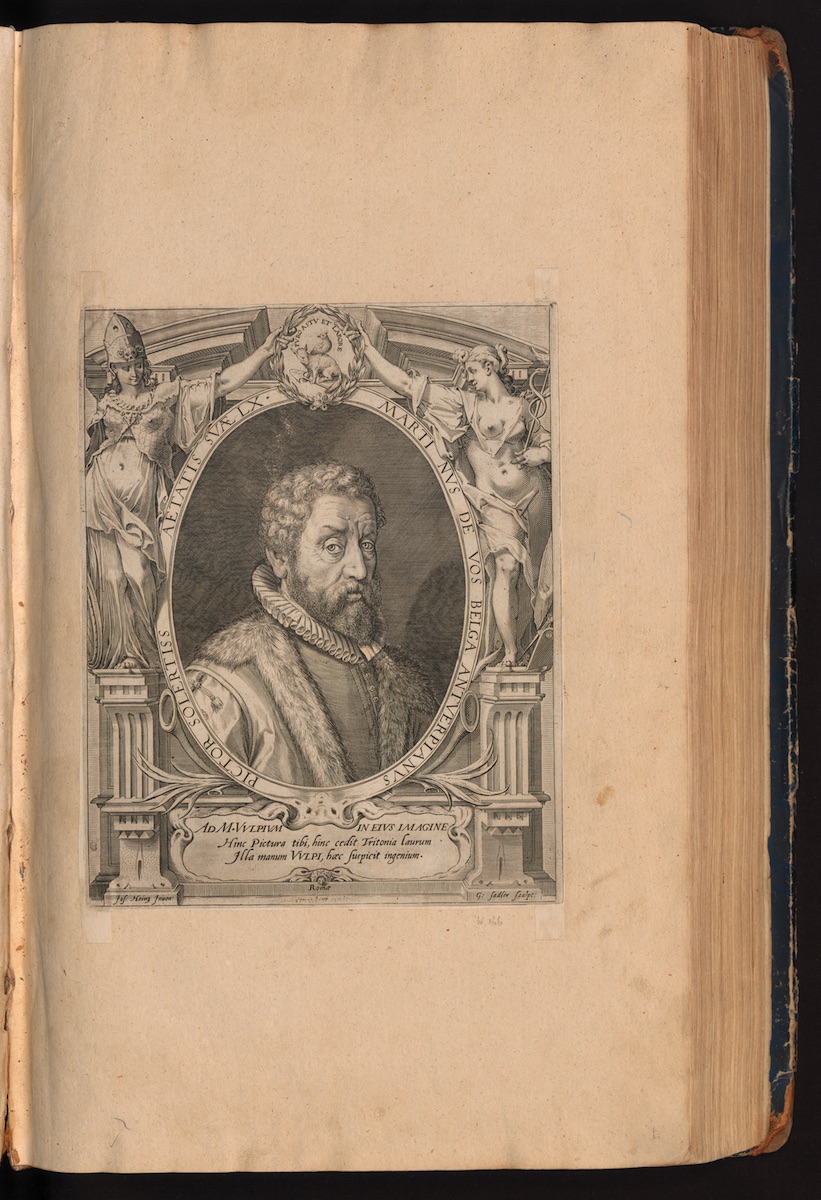

Fig. 16. Aegidius Sadeler II (after Joseph Heintz the Elder), Portrait of Maarten de Vos, 1590. Engraving, 29 x 23.3 cm. UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/2 v.1A Sadelers/de Vos f.1. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Image courtesy Baillieu Library Print Collection.

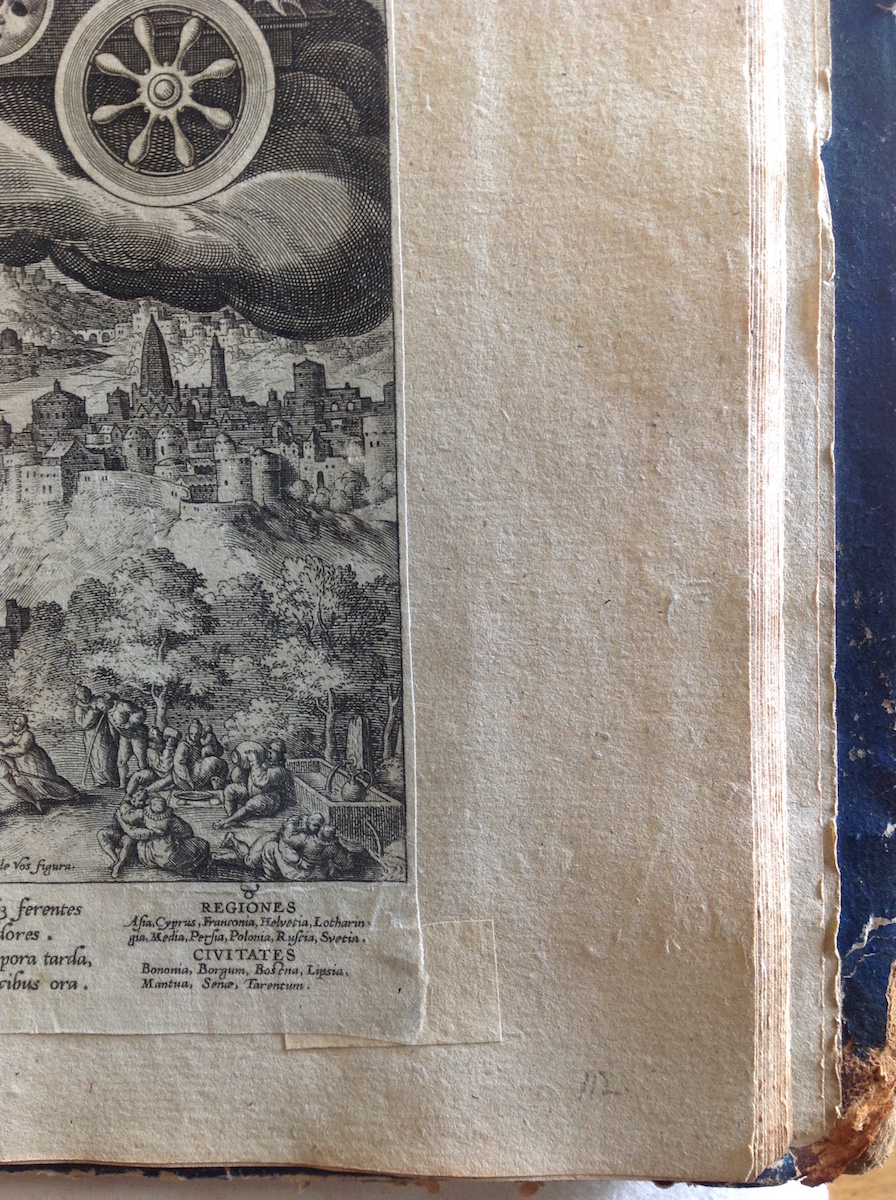

While the tabbed mounts are a unique characteristic, some other features of the De Vos albums are similar to those in other print albums assembled in the eighteenth century. For example, a portrait of Maarten De Vos by Aegidius Sadeler II is placed at the beginning of De Vos album v.1A. (Fig. 16).[58] Commencing an album with a portrait of the artist or the printmaker featured therein, and recording the number of prints it contained (as seen in the endpapers in a number of the Northumberland albums) were common practices for eighteenth-century collectors.[59] Lord Fitzwilliam included an image of the artist in the opening leaves of his single-artist albums, where he would also sign his name and record the year in which prints from his collection were sent to a specialist to be bound into albums.[60] Unfortunately, the Duchess did not record the same level of detail, though she did leave other clues about how the De Vos albums were assembled.

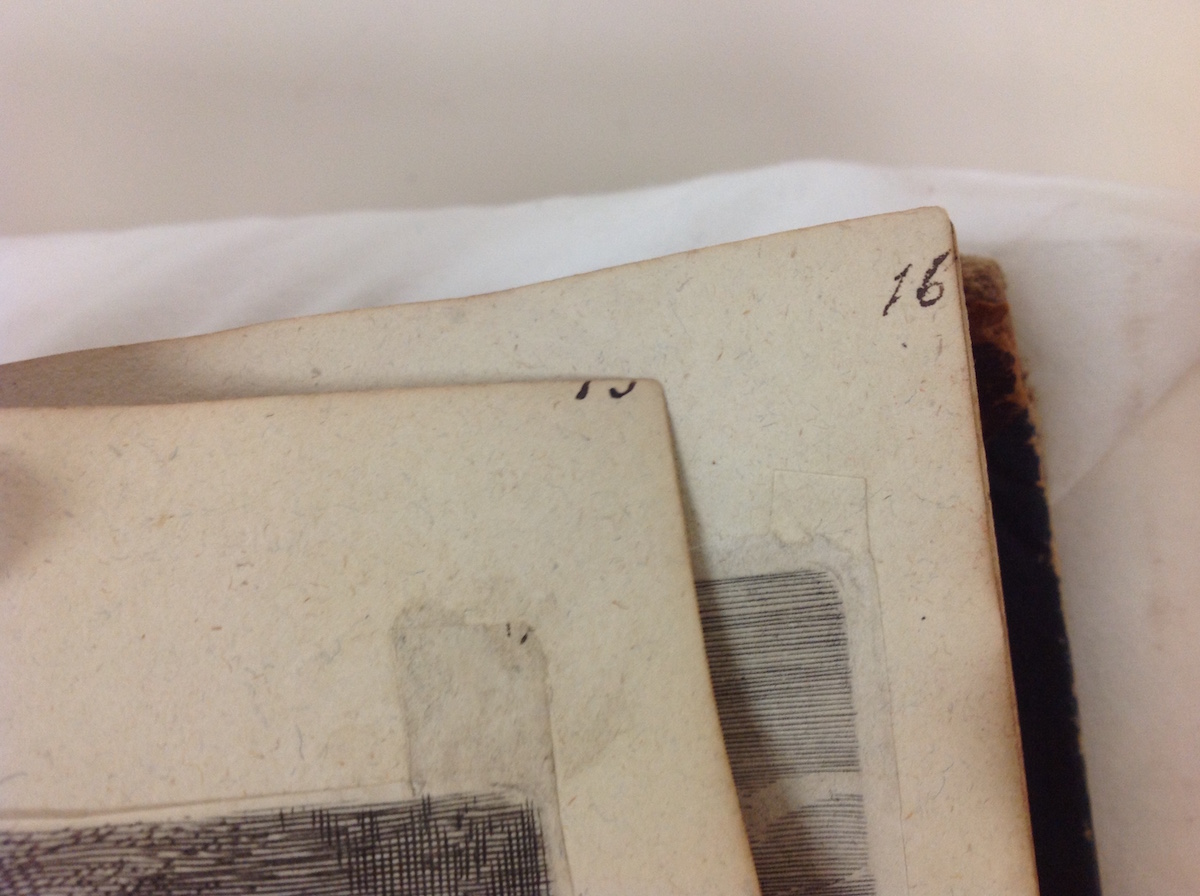

Fig. 17. Example of truncated inked foliation in UniM Bail SpC/RB 37FF/2 v.1A, Sadelers/de Vos. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

Analysis of the De Vos albums’ paper stock and foliation elucidates the assembly of individual sheets into albums. In album v.1A, for example, two different paper stocks are present, both of laid paper without a watermark. Approximately ten percent of the leaves are a heavier, slightly blue-toned paper, bound as gatherings. This stock was used for the attached endpapers, and more regularly appears on the blank leaves, indicating that it was probably added to an existing group of gatherings. There is, however, uniform discoloration of the edges of all the album leaves, indicating that both stock types were bound at the same time. Most of the leaves were foliated in ink, at the top right-hand corner of the recto, possibly by the Duchess herself.[61] The foliation is sequential—irrespective of the type of paper stock—and in some cases the foliation is truncated by the edges of the leaves, probably during the binding process (Fig. 17). The right-hand margins are narrower than the left, indicating the prints may have already been adhered when the leaves were cut for binding. These clues suggest the prints may have been first assembled onto gatherings, which were then foliated. The gatherings would then have been bound into albums—a method also used by Lord Fitzwilliam for the assembly of several of his albums.[62] Future research may uncover if it was the Duchess’ intention to have the modest “working” De Vos albums more elaborately re-bound at a later time, to match the high-quality bindings of other albums in her collection. The Duchess’ sudden death in 1776 may be the reason why the albums remained in their “working” format and binding, and why their assembly was halted “in process”.

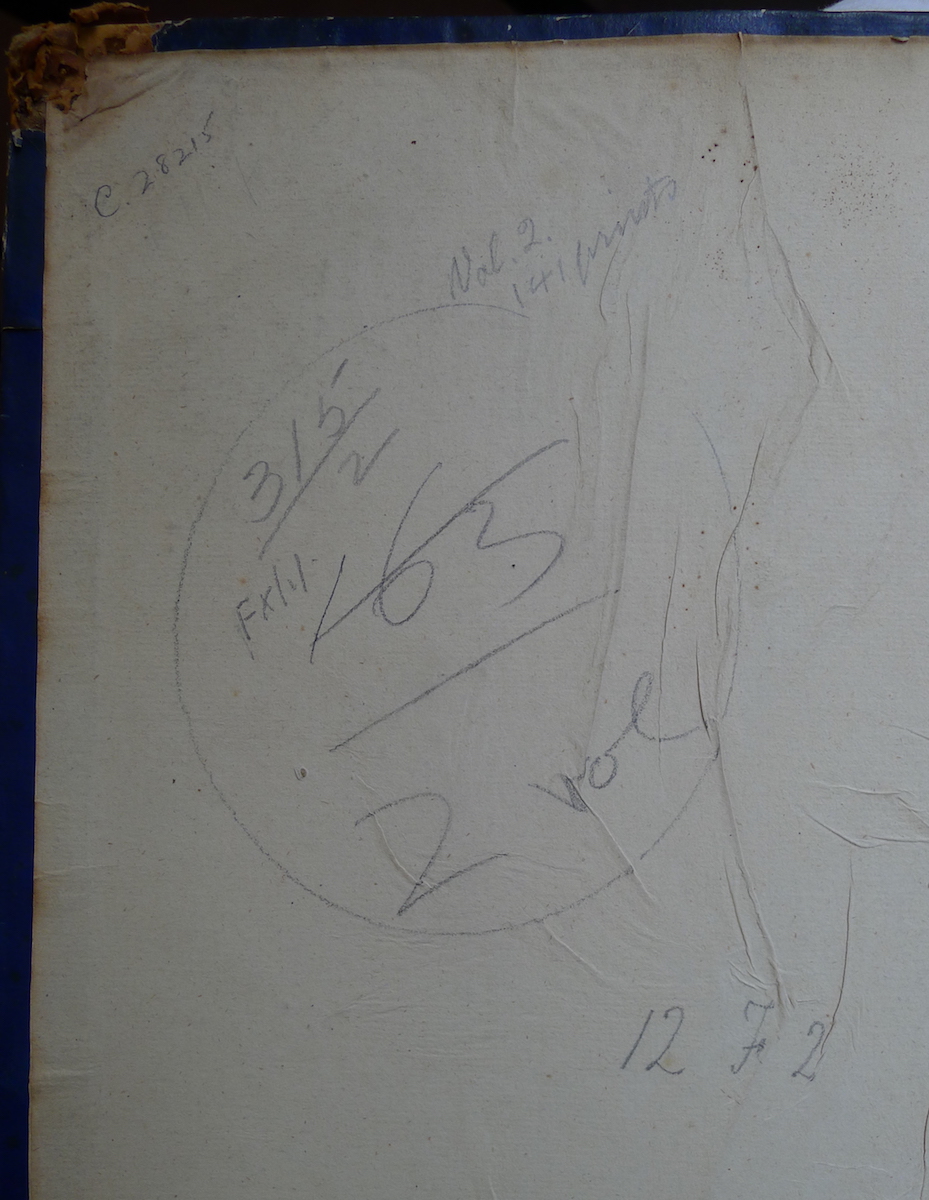

Fig. 18. Dealers’ annotations in front endpaper, with pressmark at bottom right, in UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos. Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne. Photo by author.

Other annotations provide information about the storage of the albums. Pressmarks or shelfmarks—“12 Fo 1” and “12 Fo 2”—are written in pencil in what appears to be the Duchess’ hand on the front attached endpapers of the De Vos albums (Fig. 18). A loose impression of St. Jerome bears “12 Fo” pencilled on the upper verso, in the same hand as the endpaper of the album, thus connecting the album and the print. [63] This suggests that both of these annotations were made in the Duchess’ lifetime. The pressmark therefore indicates a storage schema used by the Duchess.[64]

Two helpful lists written by the Duchess explain that her prints were distributed between the Northumberland seats: Northumberland House (London), Syon House (Middlesex), Alnwick Castle (Northumberland) and Stanwick Hall (Yorkshire). Both lists record the eighteenth-century locations of the albums now in Melbourne. A small notebook simply titled Prints notes “De Vos” at Syon and “Osborne’s Sadelers” (the Oxford albums) at Stanwick.[65] The pressmark on the De Vos albums is most likely an indication of the location of the albums at Syon House. Soon after the Duchess’ death in 1776, her prints housed at other locations were amalgamated at Syon House.[66]

Albums at the Moment of Making

As we have seen, the hand of the collector is still richly evident in the De Vos albums. The abundant and unique physical features of the Northumberland albums in Melbourne reveal new narratives about the lives of this print collection. The material traces embedded in and on the De Vos albums allow us to experience eighteenth-century print albums at the moment of making. By closely analyzing often overlooked material evidence—such as album bindings, paper stock, foliation, annotations, and mounts—it has been possible to start piecing together the intentions of the collector. We have also gleaned new insights into how these albums were collated, assembled, and stored during the Duchess’ lifetime.

I shall return to George Somes Layard for the final words: “I have given these particulars by way of indicating into what by-ways of romance, quite apart from their historical and artistic value, the collecting of engrav[ings] may lead us.”[67] To my mind, the “romance” of discovering what has been overlooked, added or consciously excised from the Duchess of Northumberland’s print albums, is perhaps more intriguing than the printed images they contain. After all, the images in these albums are multiples; impressions of the same prints can be viewed in other institutional collections. In contrast, the material features of the albums are a unique assemblage of rich data. Their marks, margins, mounts and, annotations offer a glimpse of the mind and hand of the collector as she gathered, cut, systematically arranged, and then placed prints into her albums. Through a material retrieval of the moment of making, eighteenth-century print albums become active objects, no longer “finished” works but things in-motion that reveal the process of their meticulous production.

Louise Voll Box is a PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne

Acknowledgements: This paper is dedicated to the late Dr Colin Holden. I also wish to thank Adriano Aymonino; Clare Baxter; Deirdre Coleman; Anne Dunlop; Christopher Hunwick; Kerrianne Stone; and staff at: the Baillieu Library Reading Room, University of Melbourne; the Department of Prints and Drawings, British Museum; Fondation Custodia; The Fitzwilliam Museum, and The Hunterian. Special thanks to Antony Griffiths for his advice and encouragement and for his article, “The Archaeology of the Print”, which was the catalyst for my doctoral research on the Duchess’ print collection. Research travel to the UK and Europe was generously supported by a Norman Macgeorge Travelling Scholarship (University of Melbourne), and a Research Support Grant (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art).

[1] George Somes Layard, The Headless Horseman. Pierre Lombart’s Engraving, Charles or Cromwell? (London: Phillip Allan and Co, 1922), 19.

[2] See Christy Anderson, Anne Dunlop and Pamela H. Smith, “Introduction” in The Matter of Art: Materials, Practices, Cultural Logistics, c. 1250-1750 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), 1-17; and Edward H. Wouk, “Toward an Anthropology of Print,” in Suzanne Karr Schmidt and Edward H. Wouk, eds., Prints in Translation, 1450-1750: Image, Materiality, Space (London: Routledge, 2017), 1-18 (esp. 9-10).

[3] Antony Griffiths, The Print Before Photography, An Introduction to European Printmaking 1550-1820 (London: British Museum, 2016), 426.

[4] See Adriano Aymonino, “The Musaeum of the 1st Duchess of Northumberland (1716-1776) at Northumberland House in London: An Introduction,” in Susan Bracken, Andrea M. Galdy, and Adriana Turpin, eds., Women Patrons and Collectors (Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012), 101-119. The Duchess’ travels are described in Anne French, Art Treasures in the North: Northern Families on the Grand Tour (Norwich: Unicorn Press, 2009), 59-82. See also Rosemary Baird, The Mistress of the House: Great Ladies and Grand Houses, 1670-1830 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2003), 147-168; and James Greig, ed., The Diaries of a Duchess: Extracts from the Diaries of the 1st Duchess of Northumberland (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1926).

[5] Each print has been identified in Ruth M. Edquist, Sadeler Catalogue (Parkville: The University of Melbourne, 1990), noted in following references as “Edquist.”

[6] The majority of the Duchess’ print albums were sold at auction by Sotheby’s (“The Print Library from Syon House: A Collection of Engravings Mounted in Volumes” (Day 2), Catalogue of Fine Engravings and Etchings (London: Sotheby and Co., 10-11 April, 1951), 23-43. The Melbourne albums were purchased at the sale by Colnaghi. Nearly a decade later, Colnaghi sold the albums to the University (see Angelo Lo Conte, “How One Global Collection of Old Master prints was Created: Nine Albums by the Sadeler Family in the Baillieu Library of the University of Melbourne,” Journal of the History of Collections, 30:2 (2018), 339-350. Sotheby’s lot numbers and Colnaghi stock numbers are still visible on several of the albums in Melbourne.

[7] Catalogued as UniM Bail SpC/RB: 37BB/1 v.1 John pt. 1; 37CC/1 v.1 John pt. 2; 37CC/2 v. 3 Raphael; 37EE/1 v.4 Aegidius pt. 2; 37DD/1 v.4 Raphael; 37DD/2 v. 7 Aegidius and Justo; and 37BB/2 v.8 Mark and George. For their provenance, see Antony Griffiths, “Elizabeth, Duchess of Northumberland, and Her Albums of Prints” in Dear Print Fan: A Festschrift for Marjorie B. Cohn, Craigen Bowen et al, eds., (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Art Museums, 2001), 142.

[8] Catalogued as 37FF/2 v.1A Sadelers/de Vos and 36FF/1 v.2A Sadelers/de Vos.

[9] Antony Griffiths first described the unusual tabbed mounts, and attributed the arrangement of the De Vos albums to the Duchess. See Griffiths, “Elizabeth.”

[10] Other published research on the Melbourne Northumberland albums includes: Edquist, Sadeler Catalogue; Kerrianne Stone, “The Caped Collector,” University of Melbourne Collections 18 (June 2016), 32-40; and Lo Conte, “Global Collection.”

[11] I am grateful to Christopher Hunwick for his assistance and for permission to quote from the Archives of the Duke of Northumberland. This comprehensive group of records is unique among other known eighteenth-century female print collectors, as described in Griffiths, “Elizabeth,” 144.

[12] Elenor Ling, Prized Possessions: Lord Fitzwilliam’s Albums of Prints after Adam Elsheimer (Cambridge: The Fitzwilliam Museum, 2010), 16.

[13] Marjorie B. Cohn, A Noble Collection: The Spencer Albums of Old Master Prints (Cambridge, Mass.: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, 1992), 20.

[14] The Musaeum Catalogue is housed in the Archives of the Duke of Northumberland at Alnwick Castle (subsequently “Alnwick Castle”), DNP: MS 122-127. The Catalogue of Prints is volume II (Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 122B Vol. II). Also see French, Art Treasures, 276-281.

[15] For other categories see Aymonino, “Musaeum,” 118-119.

[16] Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 122B Vol. II f.309-311.

[17] Listed under “Works of Sadeler” (Alnwick Castle, DNP: 122B Vol. II, f.311). Also under “Works of Stradanus” are 166 prints, “2 vols Miscellaneous bought at Ld Oxfords Sale” (Alnwick Castle, DNP: 122B Vol. II, f.193).

[18] Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 121/176, f.68.

[19] Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 122B Vol. II, f.311.

[20] This style of binding has become synonymous with the collections of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford. Four of the Melbourne albums were rebound in the 1990s, with the loss of original endpapers. Some of the spines have been retained. See Stone, “The Caped Collector,” 34.

[21] Griffiths, “Elizabeth,” 143, 139. Griffiths first identified this unusual feature, and also located several other Northumberland-provenance albums with tabs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Public Library (Griffiths, “Elizabeth,” 140).

[22] See Antony Griffiths, “Print Collecting in Rome, Paris, and London in the Early Eighteenth Century,” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 2:3 (1994), 37-58.

[23] Edquist IIA.91a-101a (Edquist’s Sadeler Catalogue refers to the pencil foliation in each album); Hollstein’s Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts, 1450-1700, Volume XLIV, Maarten de Vos, Christiaan Schuckman and D. de Hoop Scheffer, eds., (Rotterdam: Sound and Vision Interactive, 1996) cat. 946-963. N.H. XLIV, 946-963.

[24] Edquist IIA.91a; N.H. XLIV, 961.

[25] Edquist IIA.100; N.H. XLIV, 962.

[26] Edquist IIA.95a; N.H. XLIV, 953. The latter impressions are placed between leaves which have remnants of earlier tabs, indicating where other prints were located. Discoloration on the album leaves adjacent to these prints (which is similar to the discoloration adjacent to adhered prints) indicates that the loose prints have potentially been in the same position since the eighteenth century.

[27] Kristel Smentek, Mariette and the Science of the Connoisseur in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014), 139-142. To date, there is no evidence the Duchess had a connection with Mariette’s firm.

[28] Smentek, Mariette, 42. Antony Griffiths, “The Archaeology of the Print,” in Collecting Prints and Drawings in Europe, c. 1500-1750, Christopher Baker, Caroline Elam and Genevieve Warwick, eds. (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), 13-15.

[29] Lists of printsellers, bookbinders, engravers and stationers are recorded in Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 121/63, f.130,134,139.

[30] There is no evidence on the versos of prints in the De Vos albums, or on the albums leaves, to indicate the tabs were delineated in pencil or otherwise marked before being cut.

[31] Griffiths, Print Before Photography, 411-12, 424. Pepys’ extensive collection was also only pasted into albums at the end of his life. See Jan van der Waals, “The Print Collection of Samuel Pepys,” Print Quarterly 1:4 (1984), 239.

[32] The quantity of notes by the Duchess about prints reveals she thought carefully about her collection, so it is possible that the tabs were her own invention.

[33] See for example: David Pullins, “The State of the Fashion Plate, c. 1727: Historicizing Fashion between ‘Dressed Prints’ and Dezallier’s Recueils,” in Prints in Translation, 136-157; Ann Massing, “From Print to Painting. The Technique of Glass Transfer Painting,” Print Quarterly 6:4 (1989), 383-393; Lucy Peltz, Facing the Text: Extra-Illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain, 1769-1840 (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 2017); and Noël Riley, The Accomplished Lady. A History of Genteel Pursuits c. 1660-1860 (Leeds: Oblong, 2017).

[34] The Duchess was an active collector of portrait prints, as noted by Horace Walpole (Peltz, Facing the Text, 51). For example, eight folio volumes of portrait prints related to the “Reign of K. George 3rd” (Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 122B, Vol. II, f.213) were sold in the 1951 Sotheby’s sale (see endnote 6) as lot 350. There is no evidence to date that these or other albums were assembled and adhered “within the framework of a pre-existing text,” according to Peltz’s definition of “extra-illustration” (Facing the Text, 5).

[35] Griffiths, Print Before Photography, 424-5.

[36] Griffiths, Print Before Photography, 425.

[37] To date, no evidence of the Duchess’ motivation or inspiration to use tabs is apparent from her notebooks or correspondence. The motivation for extra-illustration of texts with prints in the eighteenth century is similarly “seldom recorded directly” (Peltz, Facing the Text, 4).

[38] Griffiths, “Elizabeth,” 139. The author’s enquiries to print specialists in several countries have not revealed any examples of this technique used by other collectors.

[39] Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 121/60 f.38-39.

[40] Jean Vilet was a drawing master and the Duchess’ valet de chambre when travelling (French, Art Treasures, 69).

[41] Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 121/43 f.23.

[42] Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 121/43 f.12.

[43] Peter Parshall suggests the compilation of print albums collected by Ferdinand, Archduke of Tyrol (1529-1595/6) was allotted to “librarians, artists and other specialists” within the court (“Art and the Theater of Knowledge: The Origins of Print Collecting in Northern Europe,” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 2:3 (1994), 22.

[44] Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 122B Vol. II, f.311.

[45] Edquist IA.2-6a; N.H. XLIV, 11-18.

[46] Edquist IA.3a; N.H. XLIV, 12. Similarly, on the leaf under the title page for the series, described in Hollstein as “On Title: Imago Bonitatis Illius,” we find the words “Image Bonitatis Illius,” written in the Duchess’ hand. (H. XXI 85.9 (J. Sad. I); Edquist IA.2; N.H. XLIV, 11).

[47] Edquist IA.9a; N.H. XLIV, 29 II (Series: N.H. XLIV, 25-36 II).

[48] Another finer impression of this print with all lettering covered is also in an Oxford album: Edquist I.52a.

[49] Edquist IA.110a-113b; N.H. XLIV,1380-1387.

[50] For the placement of N.H. XLIV,1506-1510 in v.1A. Not described in Edquist, Sadeler Catalogue.

[51] Beth Fowkes Tobin, The Duchess’s Shells—Natural History Collecting in the Age of Cook’s Voyages (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 59.

[52] See Griffiths, The Print Before Photography, 169-175.

[53] Aymonino claims the overall structure of her collection was “a tangible expression of the absorption and use of the new ‘Enlightened’ notions by a private amateur,” but with her prints (and also with her medals and coins) she “clearly showed a high level of discernment” (Musaeum, 116).

[54] Several prints are also replicated in the Oxford albums. In these albums, however, much of the lettering has been removed as part of the encapsulated mounting process, and only some prints are loosely arranged in numerical or series order.

[55] Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 121/176, f.75-76.

[56] Timothy Clayton, The English Print 1688-1802 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997), 126. The albums of Sadeler prints now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (see Griffiths, “Elizabeth,” 140) are noted in the Duchess’ Catalogue of Print as “Darres’s Sett” which most likely indicates their purchase from Darres (Alnwick Castle, DNP: 122B V.II, f.309).

[57] Alnwick Castle, DP: D1/II/19 (n.p). The script is reminiscent of the Duchess’ handwriting in the 1740s and 1750s.

[58] Edquist IA.1. Hollstein’s Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts ca.1450-1700, Volume XXI, Aegidius Sadeler to Raphael Sadeler II, Dieuwke de Hoop Scheffer and K.G. Boon, eds. (Amsterdam: Van Gendt and Co, 1980), 75 cat. 340. H. XXI.

[59] Griffiths, Print Before Photography, 424.

[60] Ling, Prized Possessions, 20.

[61] The numerals 9, 10, and 16 have the distinctive features of the Duchess’ hand.

[62] Particularly those assembled after 1808. Ling, Prized Possessions, 15.

[63] Edquist IIA.115; H. XXI 30.102 (Aeg. Sad.).

[64] Pencilled pressmarks also appear in two of the Oxford albums (37 EE/1 v.4 and 37BB/2 v.8). These annotations are most likely related to post-1847 inventories or to the collation of the collection for sale by Sotheby’s, as annotations in the same hand also appear on Northumberland-provenance albums sold by Sotheby’s and now located at Fondation Custodia (Lugt Inventory Number 6437), RKD in The Hague (Previously Lugt Inventory Number 6440), and the British Museum (Object number: 2010,7081.344).

[65] Alnwick Castle, DP: D1/II/5 (n.p.). Another notebook records: “Sadelers 1 Syon / Ditto London / Osborne’s Stanwick / Sadelers 4 Alnwick” (Alnwick Castle, DNP: MS 121/176 f.98).

[66] A receipt from July 1785 describes: “delivered at Syon House 76 Books of Prints &c. of different sizes, taken from Northumberland House” (Alnwick Castle, DNM: D/2/6). The location of the collection can next be traced through an 1847 Syon House inventory (“Inventory of the effects at Syon House”, Alnwick Castle, Sy: H. VIII 1.b, f.150-295) which describes the albums now in Melbourne and their shelf locations at that time: “Print Room A, Shelf 3” (the Oxford albums) and “Print Room A Shelf 4” (the De Vos albums) (f.275).

[67] Layard, Headless Horseman, 19.

Cite this article as: Louise Voll Box, “Marks and Meanings: Revealing the Hand of the Collector and ‘the Moment of Making’ in two 18th-Century Print Albums,” Journal 18, Issue 6 Albums (Fall 2018), https://www.journal18.org/2929. DOI: 10.30610/6.2018.6

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.