Chelsea Foxwell

“[T]he lilt of a flying wasp, the pitch of a flying duck, a mantis in fighting position, or a semi [cicada] toddling up a cedar branch to sing. All this art is alive, intensely alive, and our corresponding art looks absolutely dead beside it.”

— Lafcadio Hearn, 1893[1]

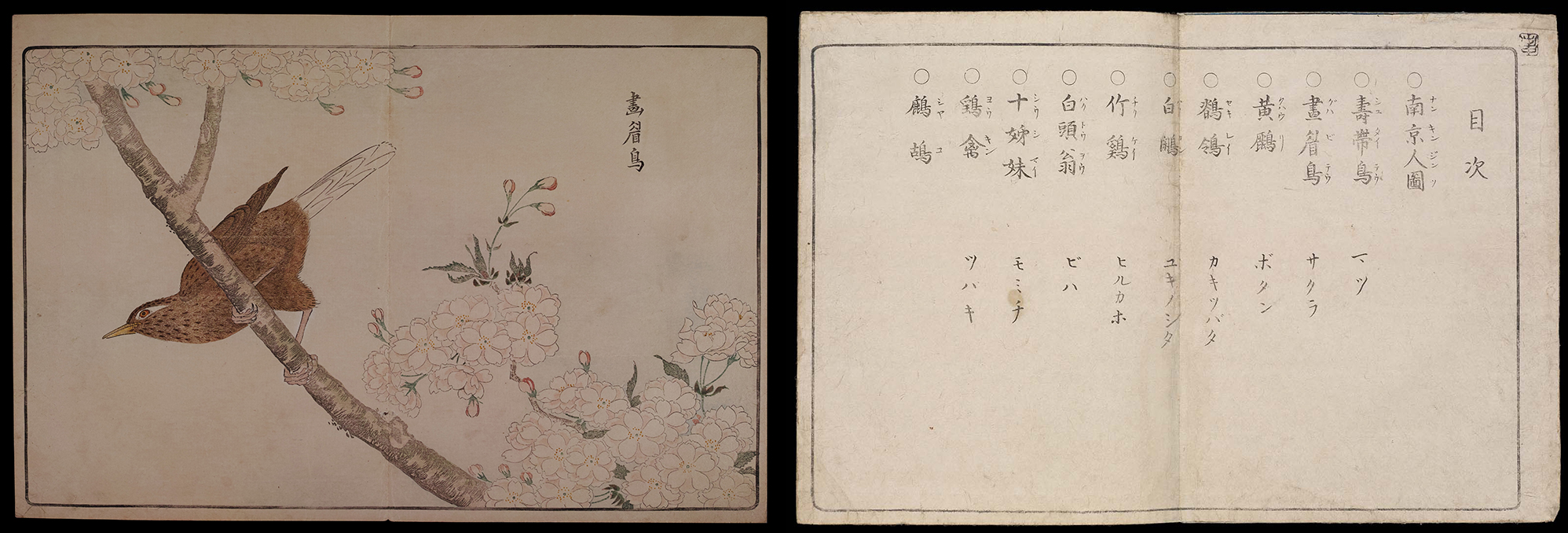

The global trade in exotic birds and animals, backed by ancient aristocratic practices and expanded by the Dutch and other traders, touched communities on every populated continent in the eigthteenth century. The logistics of efficient long-distance transport of exotic fauna balanced cost-effectiveness with the task of keeping the cargo alive.[2] Across all of these communities, pictures traveled when and where the real creatures could not, and in the city of Edo (present-day Tokyo), the newly developed process of color woodblock printing offered the potential to further disseminate such images beyond the ruling elite.[3] This article offers an account of one such set of images, the 1790-91 Illustrated Book of Birds from Abroad (Kaihaku Raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙, Figs. 1-4) by (Kuwagata) Keisai Kitao Masayoshi 惠斎北尾政美 (1764-1824; henceforth Keisai).[4] This book ranks alongside the famed contemporaneous insect and bird books of Kitagawa Utamaro 喜多川歌麿 (1753-1806) as one of the earliest and most lavishly printed sets of ukiyo-e bird and flower prints in Edo-period Japan (1615-1868). But while Utamaro’s book begins by declaring its aim of representing the birds and flowers of “our country Japan” as the companion for playful vernacular poetry (kyōka), the identity of Keisai’s Book of Birds From Abroad, as the title declares, was bound up with the culture of foreignness. In particular, the book engaged with aspects of recent Chinese science and culture that flowered in Japan’s only foreign merchant port of Nagasaki.

LEFT: Fig. 1. Keisai Kitao Masayoshi, “Huangli (kōri) and peonies,” 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

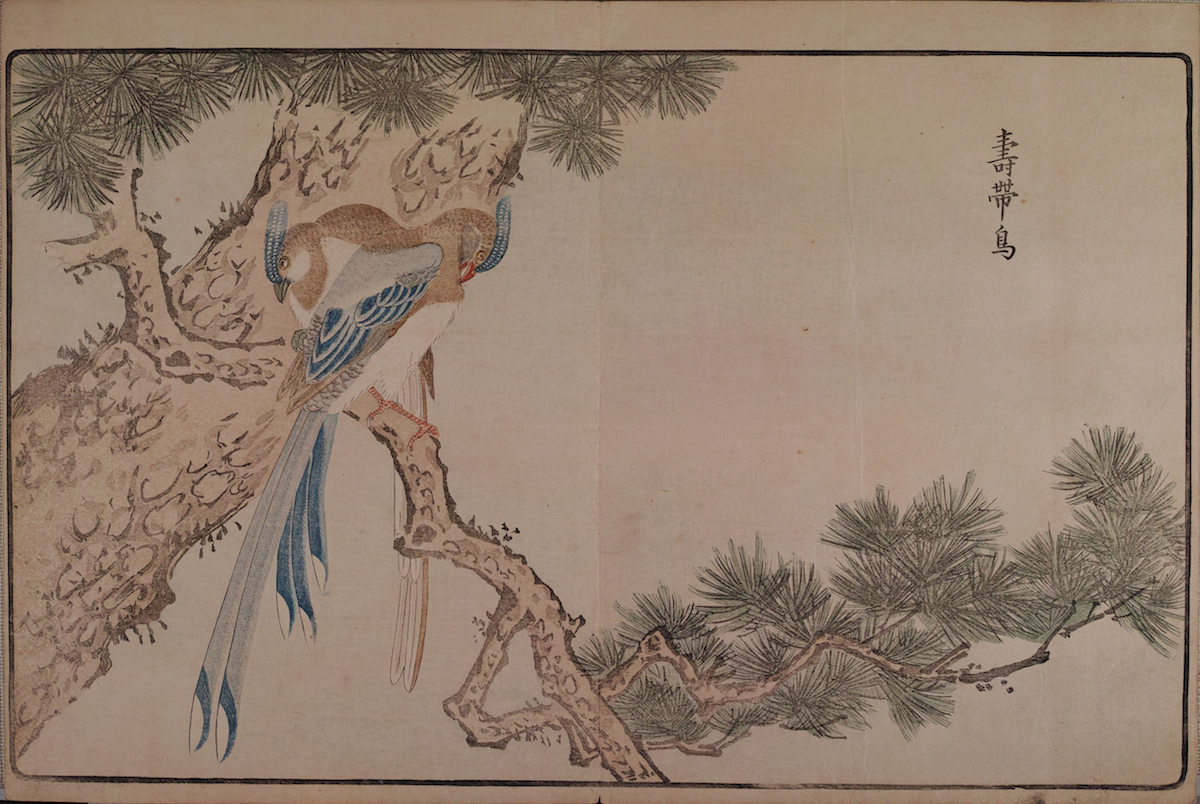

RIGHT: Fig. 2. Keisai Kitao Masayoshi, “Eurasian jay (Yōkin) and camelia,” 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

LEFT: Fig. 3. Keisai Kitao Masayoshi, “Hwamei (gabichō) and cherry blossoms,” 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

RIGHT: Fig. 4. Seki Mitsufumi (Eibun), Table of contents, 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

According to its front and back matter, this book, which was designed and printed in Edo, is supposed to be a copy of paintings of real birds that entered Nagasaki on Chinese ships. The names of Chinese artists and merchants are prominently displayed in support of this assertion, and the book’s artfully composed color pictures appear “intensely alive,” as Lafcadio Hearn later wrote of an analogous unspecified work. But while viewers have long appreciated the realism of Birds from Abroad, that realism was highly mediated, both culturally and pictorially, in a way that its viewers were expected to understand and even savor. The conventional understanding of realism suggests immediate access to the object of depiction—a type of immediacy that Birds from Abroad evokes in its preface. But the construction of what Roland Barthes has called “reality effects” (l’effet de réel) in the minds of viewers can result from the complex coordination of literary and artistic devices.[5] Along these lines, Birds from Abroad was the result of successive acts of transfer and reenvisioning with reference to other source works as the project evolved in response to cultural, financial, and artistic concerns, and it is likely that its initial viewers in the early 1790s were highly attuned to such aspects of knowledge transfer and prestige. A search for the now-lost originals on which the book was based complicates its identity and raises broader questions about what it meant for a woodblock-printed book to disseminate copies of an “original”—whether natural specimen or manmade artifact—in late eighteenth-century Japan.

Foreign Birds, a Deluxe Volume

When the Illustrated Book of Birds from Abroad first appeared, the colorful bird and flower prints of Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重 (1797-1858), such as the former’s Large Flowers (1833-34), had yet to be produced. Indeed, commercially available, color-printed bird and flower pictures had not yet emerged as a genre in woodblock printing. Following Utamaro’s peerless insect book of 1788-89, his similarly famous Myriad Birds: Paired Kyōka (Momochidori kyōka awase 百千鳥狂歌合) was likely published simultaneous with, or just prior to, Birds from Abroad. Utamaro’s work was allied with the poetic genre of kyōka and was deeply fanciful in nature, with birds of different species facing off in a competition of verses. Although Keisai’s teacher Kitao Shigemasa 北尾重政 (1739-1820) is known to have authored at least one book of plants and flowers to accompany haikai (short, linked verse) poetry in the 1780s, Shigemasa’s surviving bird and flower works postdate the Birds from Abroad, and instead should be seen as addressing the popular demand that was created in its wake.[6]

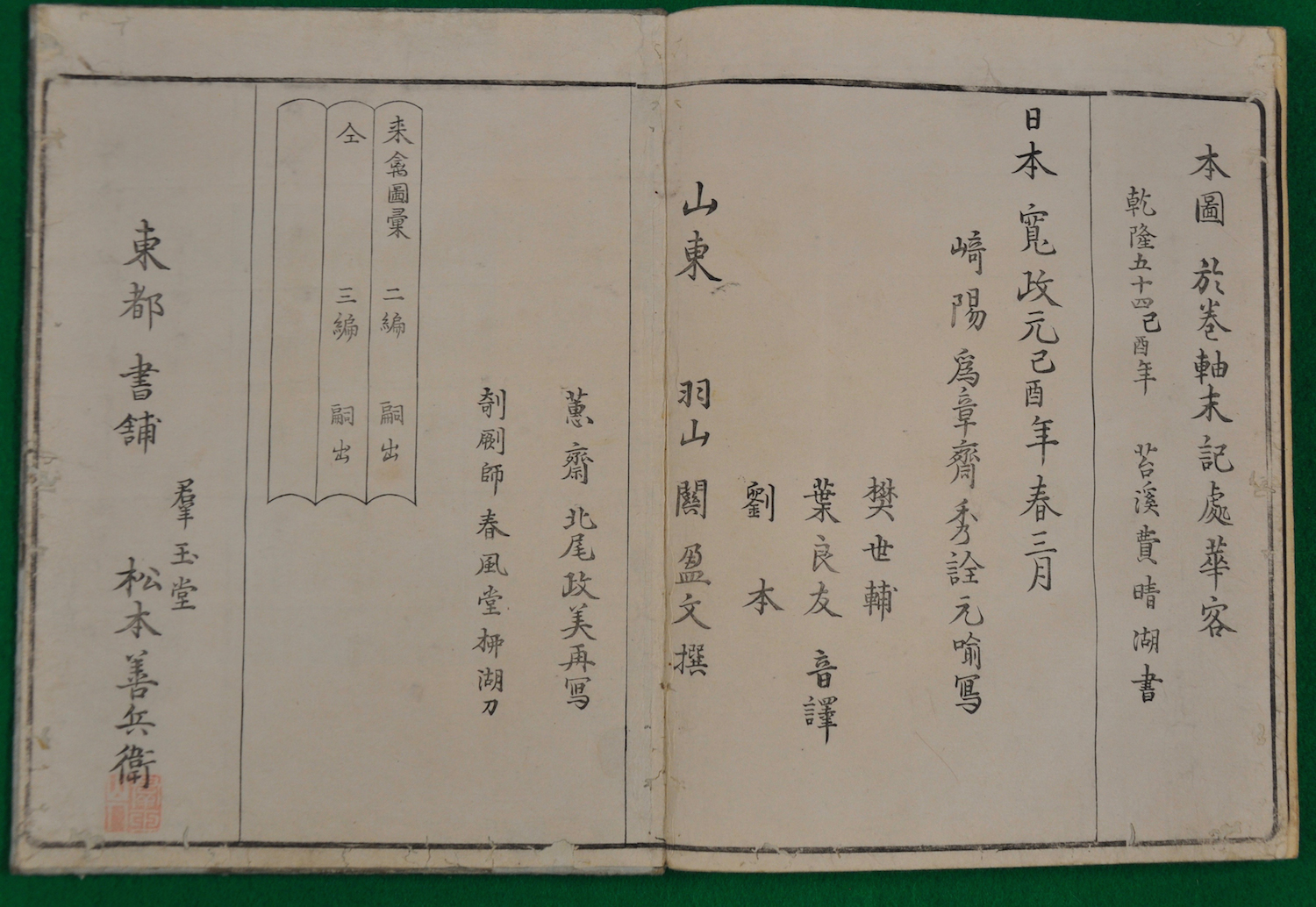

In contrast to these works that paired birds with poetry, the Book of Birds from Abroad focused on the documentation of foreign bird species and the dissemination of pictures from Nagasaki. Stately and elegant, it was a project of a wholly different order from any work hitherto associated with Keisai. Ten balanced compositions of exotic birds in various attitudes are accompanied by seasonal blooms and trees such as camellia, peony, pine, and loquat. The images exhibit pale over-printed hues, delicate embossing, “boneless” (mokkotsu 没骨) unoutlined areas of pure color, and other characteristics of deluxe printing. The book did not list Keisai as the artist of these images; that honor went to a Nagasaki artist called Isshōsai Shūsen Gen’yu 為章斎秀詮元喩, whose paintings, notes the publication page, received an inscription by the Nagasaki-based Chinese painter Fei Qinghu 費晴湖 (dates unknown) dated to the fifty-fourth year of the Qianlong era (1789).[7] Keisai’s name appears in the middle of the book’s final page, where he is credited as having “re-copied” (再写) the pre-existing bird paintings by Shūsen (Fig. 5). In comparison, the preface and back matter of Myriad Birds: Paired Kyōka prominently credit Utamaro as its artist or painter (gakō 画工). The Book of Birds From Abroad not only minimized Keisai’s role, but also promised viewers access to rare elements of recent Chinese culture and learning from distant Nagasaki, a place that Keisai likely never visited.[8]

Fig. 5. Publication data page, Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙), 1790-1791. Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

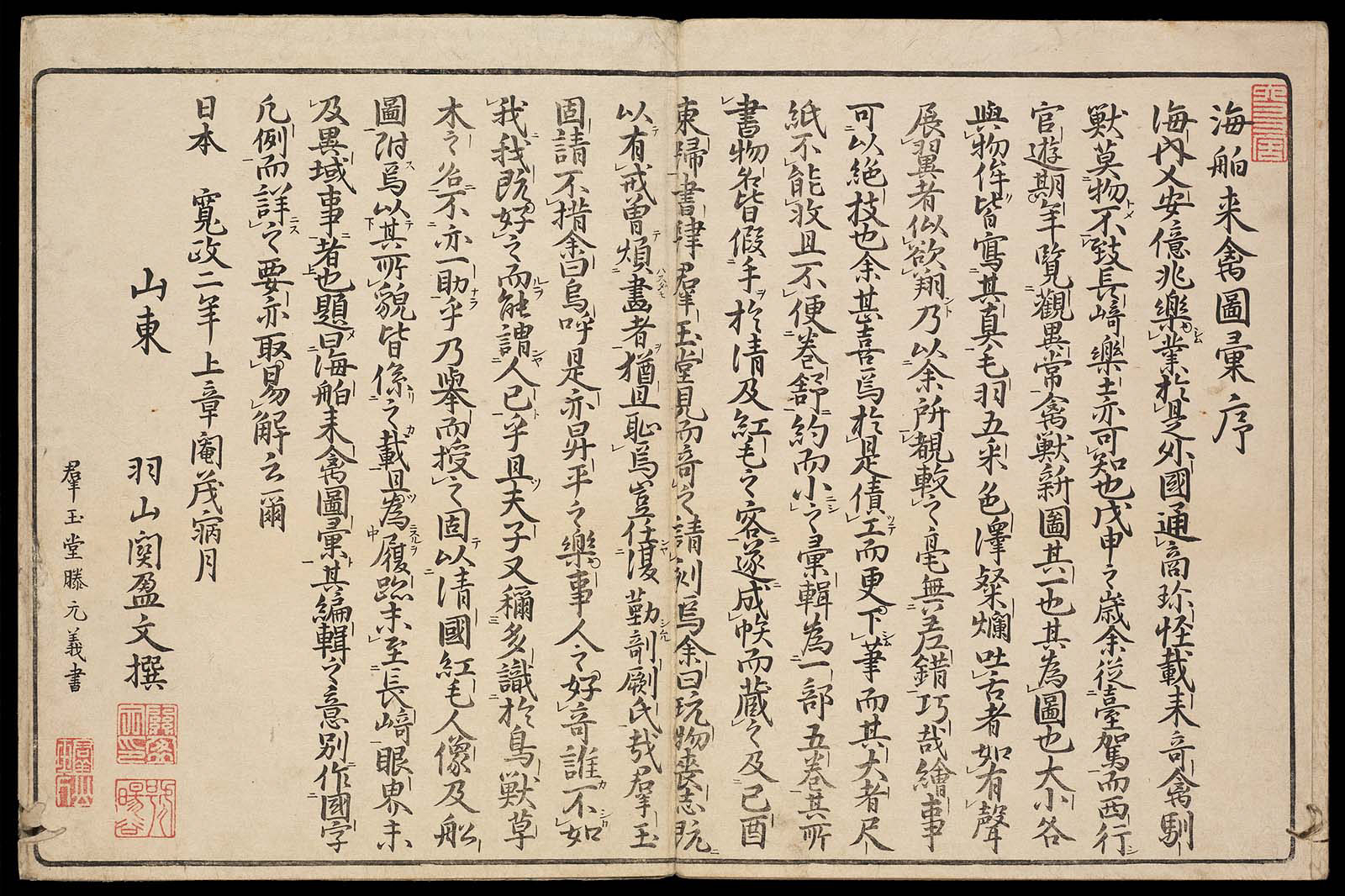

The book’s preface describes the multi-step process by which it conveyed rare pictures of exotic birds to audiences in Edo and beyond. The author of the preface, Seki Mitsufumi (Eibun) 関盈文 (dates unknown), a samurai official in the service of the shogun, claims to have viewed paintings of live exotic birds at the office of the Nagasaki Magistrate (Nagasaki Bugyōsho 長崎奉行所), where he had been dispatched. After having his own hand-painted copies made by a local artist, Seki returned to Edo in 1789. Within a year or two, the Edo publisher Matsumoto Zenbe’e 松本善門兵衛 (dates unknown) had published a small selection of the images as the Illustrated Book of Birds from Abroad, a fully color-printed album of twelve pictures and a preface that would later become known as one of the most exquisitely printed illustrated books of the entire Edo period.[9] The artist engaged for the project was the young Kitao Masayoshi, also known as Keisai, a disciple of Kitao Shigemasa. Keisai was the son of a tatami mat maker, and his main work at the time consisted of illustrating popular short fiction “yellow cover books” (kibyōshi 黄表紙).

Birds From Abroad presents exotic birds accompanied by plants and trees that appear in a sequence approximating the passing of the seasons. For example, in the first image, a pair of connubial red-tailed blue magpies (jutaichō 寿帯鳥; Urocissa erythrorhyncha) birds nestle in the boughs of a deep green pine tree, associated with winter (Fig. 6). The birds’ plumage is printed in dark and light blue, with fine embossed lines suggesting the white down of the bellies and cheek feathers. The mottled brown plumage of the heads and necks is attained through sensitive overprinting, and the black keyblock outlines typical of prints made in Edo are withheld from the birds’ heads, necks, and wings to create soft contours. Male and female attributes, such as the color of the bill, feet, and plumage, are carefully distinguished. The eyes, printed in red and black and rimmed with yellow, accord with specimens observed today, and suggest that information had been gleaned from observing live birds.[10] As with many of the other images in the volume, the compositions are serene, and reward close looking.

Fig. 6. Keisai Kitao Masayoshi, “Red-billed blue magpie (jutaichō) and pine tree,” 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

The Production Narrative of Birds from Abroad

Through its front and back matter, the Book of Birds from Abroad can be seen to indirectly advance two claims. First, that the book faithfully transmits lifelike paintings of actual birds; and second, more indirectly, that it is closely associated with Chinese culture in Nagasaki. The front matter consists of an inside front cover (missing in some surviving editions; see Fig. 17), a Chinese preface (kanbun jo 漢文序), dated to the ninth month of Kansei 2, or October of 1790, Appendix A) (Fig. 7), and a foreword of notes to the reader written in the Japanese vernacular (wabun hanrei 和文凡例, Appendix B).[11] From these notes, we learn that the book originated with Seki’s Nagasaki sojourn. At the office of the magistrate where he had been dispatched, Seki recounts that he saw life-sized depictions of the live birds and animals that had entered Japan on foreign ships. He was so taken with them that he decided to have his own copies made, but for the sake of convenience, the new copies were smaller in size and omitted some of the details. Seki’s preface states that after he brought the paintings back to Edo, the bookseller Matsumoto Zenbe’e requested to copy and publish a portion of them to benefit people who delight in unusual things—although here it may be more reasonable to reverse the portrayed power relationship, and instead speculate that Seki served as the project editor who sought a publisher for his images.

Fig. 7. Seki Mitsufumi and Matsumoto Zenbe’e, “Kanbun preface,” 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Japanese foreword adds a further nuance to the production narrative. It begins: “These pictures were all offered up to the Eastern Capital” (hon zu wa kore mina tōto e kenzuru tokoro nari 本図ハ是皆工東都献スル所ナリ). This implies, somewhat grandly, that the viewer or consumer of Seki’s book is setting eyes on images that are not only rare and truthful, but also intended for the most privileged figures in the archipelago: namely, the shogun and other governing authorities. With this device, the Illustrated Book of Birds from Abroad also works to attract viewers by allowing them to glimpse a set of images intended for the highest levels of the political class.

Eighteeenth- and early-nineteenth-century Japan was officially stratified by class and social status. Both traditional custom and Tokugawa shogunal edicts mandated that the affairs and possessions of each elite household (those with samurai status and members of the nobility) were unsuitable for publication, public discussion, or any other form of access by the lower classes.[12] But since many artists, including Keisai, were themselves commoners, how were they to examine paintings and other artistic treasures in elite collections? For that matter, how were elite artists in the service of one lord supposed to learn about great paintings in others’ collections? The answer lay, in large part, in the production and circulation of copies. The ability to view a cherished work and to make a detailed copy was itself an achievement, warranting reflection on the social capital and fortuitous circumstances that enabled a humble artist to gaze upon a prized possession of the ruling elites.[13] And while woodblock-printed compendia of famous Chinese and Japanese paintings (known variously as gafu 画譜, ehon 絵本, edehon 絵手本, gakan/ekagami 画鑑, etc.) became more common in Japan over the course of the eighteenth century, initial concerns about infringing on the rights of the original paintings’ powerful owners help to explain why the first such books were not published in Edo. Instead, they were produced in the Kyoto-Osaka region, further from the shogunal authorities, and by Kano school painters (who held samurai status) as opposed to ukiyo-e designers (who tended to be commoners).[14] For these reasons, we should pay close attention to the chains of access and transmission that engendered the Book of Birds from Abroad and were in turn documented in its pages.

As described in the preface, foreword, and publication page, the Book of Birds from Abroad indexed at least three levels of copying. First, a Nagasaki artist of unspecified nationality, Ishōsai Shūsen Gen’yu 為章斎秀詮元喩, created “new pictures of [live] birds and animals” for the Nagasaki Magistrate’s office. In the preface, Seki recounts:

Each picture’s size was the same as the thing represented, and all depicted the truth. The colors of the feathers and fur, the sheen and brilliance: the ones with the tongue out seemed as though they had a voice. The ones with wings outstretched seemed ready to depart. Comparing it with what I saw [i.e., the actual birds(?)], there was not the least bit of difference or error.

Seki then hired another artist at his own expense to make what ultimately amounted to five volumes of reduced-scale sketches, adding that “duplicate copies of these paintings are all the closely guarded possessions of the artist” (sono fukuhon mo mata mina gaka no chōhi nari 其副本モ亦皆画家の帳秘ナリ). This can be interpreted to mean that the images eventually published in Birds from Abroad originally existed in four formats: a set of paintings after live birds and animals that were offered to the shogun in Edo; “duplicates” of those paintings in the closely guarded possession of the Nagasaki artist (either Shūsen or the artist that copied the works for Seki); a set of smaller paintings by an unnamed artist that Seki hired; and finally, a set of pictures brushed by Keisai in Edo for the purpose of being carved and printed into a colored album. As the underdrawings for woodblock prints were usually pasted to the blocks to guide the carver, and thereby destroyed in the carving process, Keisai’s hand-brushed pictures are unlikely to have survived.

As previously mentioned, the preface and foreward of the Book of Birds from Abroad refer to Chinese names, symbols, and imagery for legitimacy and present the Edo painter Keisai as a mere transcriber who “re-copied” (再写) pre-existing paintings by Shūsen. The book is literally wrapped in figures from China: the first and last pictures depict Chinese merchants by the sea, bracketing the bird and flower images within and allowing the book to open and close with images of rolling waves. The image at the front of the book is labeled “A Picture of People from Nanjing” 南京人圖, and includes an arriving man leading a live goat and a boy transporting a slaughtered rooster that reflect the Chinese practice of eating meat from domesticated animals (Fig. 8). The final image in the book shows Chinese traders seated on a red lacquer chest with bolts of cloth and a caged bird (Fig. 9). They face toward the sea, and the cursive Dutch writing labeling the “Chineesen…van Nankin” adds another level of mediation—and of foreignness—to the image, suggesting that the picture of the Chinese traders may have been sourced through a Dutch ethnographic image intended for curious viewers in Europe.

Fig. 8. Keisai Kitao Masayoshi, “People from Nanjing,” 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

Fig. 9. Keisai Kitao Masayoshi, “Chineesen…van Nankin,” 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

The first and last pages of text in the book likewise refer to China. The final page of publication data (see Fig. 5) begins with the name of a well-known Chinese painter resident in Nagasaki, Fei Qinghu of Taixi 苔溪. Fei is credited with having brushed a colophon on the original images dated to the fifty-fourth year of Qianlong (1789), though no such colophon is reproduced in the book.[15] The inside front cover (see Fig. 7) mentions Fei again, together with Cheng Chicheng 程赤城 (1735-?), introducing them as Nanjing Chinese who inspected the book for accuracy (閲 etsu). Both Chinese men were long-time residents of Nagasaki and noted for their involvement in painting and calligraphy. Modern scholars once speculated that the Shūsen, the painter credited with producing the original bird images, was in fact a Chinese painter; given the book’s emphasis on Chinese authorial involvement, the Edo residents of Keisai’s day could have been forgiven for making the same assumption.[16] It is now clear that Shūsen must have been Watanabe Shūsen 渡辺秀詮 (1736-1824), one of the Watanabe house of official painters (御用絵師 go’yō eshi) and Chinese painting appraisers (kara-e mekiki 唐絵目利) who were employed for generations at the Nagasaki magistrate to document and appraise paintings and other items that arrived on Chinese and Dutch ships. In short, despite the book’s clear Chinese emphasis, the authors of the text and the images, along with the publisher, were all Japanese, including Shūsen, the painter whose source images are credited in the book.

“To Assist in Creating a Mood:” Changes to the Bird Images in Edo

What did Watanabe Shūsen’s original paintings look like? The Kobe City Museum owns two paintings by the artist-official: a hanging scroll of a large-eyed, highly conventionalized tiger, a theme for which he was known; and a long handscroll on silk of the Chinese traders’ district of Nagasaki.[17] The lifelike bird paintings that Seki saw were presumably closer to a set of sketches of imported birds executed by Shūsen’s successor as head of the Watanabe house of painters and appraisers, Watanabe Shūjitsu 渡辺秀実 (also known as Kakushū 鶴洲, 1778-1830) (Fig. 10). The works that impressed Seki were probably also related to a set of official images of exotic fauna now divided among several Japanese collections including Keio University (Fig. 11).[18] According to Isono Naohide, these surviving images were the duplicates kept by the Nagasaki magistrate as a record of paintings of exotic birds that were sent to the shogun. The birds are usually situated on a manufactured perch or shown against a blank background, since they were imported to Japan as commodities rather than being observed in the wild.[19] The birds are almost always depicted in profile and usually do not strike dramatic or complex poses, but stare calmly out at the viewer from their perch or the ground. As art historian Kagesato Tetsurō opined in another context, for documentary images of goods and specimens in Nagasaki, “detailed life drawings were what was sought, so there was no need to concern oneself with a particular style or school of techniques; neither was there any need to express any artistry or value from an artistic perspective. So long as the goal [of visual transcription] was met, the artistic methods did not matter.”[20] While we should guard against an excessively stark delineation between the art of painting and the labor of detailed transcription, nevertheless Kagesato’s assertion reflects the general working parameters of numerous Nagasaki-based artists who were charged with documenting goods and specimens there. In this context, the addition of the complex poses and unusual vantage points seen in typical bird and flower paintings would have been irrelevant to the task at hand. Accurate visual documentation was particularly important because many of the newly arrived objects were unknown and lacked Japanese names.[21]

Fig. 10. Detail of Watanabe Kakushū and school, Life sketches of birds (Chōrui shasei zu 鳥類写生図) , late eighteenth-early nineteenth century. Handscroll, ink and color on paper. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

Fig. 11. Unidentified artist, “Red-billed blue magpie (sanjaku).” From Pictures of Foreign Birds (Gaikoku san tori no zu 外国産鳥之図), 1727-1808. Handscroll; ink and color on paper, National Diet Library, Tokyo.

According to the preface and foreword of Birds from Abroad, it is clear that the lifelike and detailed qualities of the original bird paintings are what impressed Seki, whose interest in the project had never been purely artistic: he went on to write a companion volume of natural history notes for each bird that had been pictured in the color-printed volume. The Japanese foreword to Birds from Abroad notes: “Because [Shūsen’s bird paintings] directly copy the truth” (jiga ni sono shin o utsusu ga yue ni 直ニ其真ヲ写スガ故に), as far as the light and colors of the feathers, fur, and scales, [their accuracy] scarcely needs reiterating. Concerning the size, they are all the same as [the specimen they represent], just as stated in the preface.” Seki clearly prioritized accuracy of scale and coloration.

As noted above, documentary drawings of exotic birds produced in Nagasaki exist in Keio University and other repositories. In addition to their consistent blank background, simple poses of the birds, and manmade perches, they also tend to include details about the birds’ date of import to Japan, and occasionally also an indication of the region of origin. Seki’s text companion to Birds from Abroad includes this information, noting, for example, that several of the birds portrayed were imported on specific Chinese ships in the Hōreki (1751-1764), Meiwa (1764-1772), and adjacent eras. It is therefore likely that Seki did have the opportunity to observe such documentary images. At the same time, however, there are pronounced differences between Watanabe Shūjitsu’s pictures of imported birds and the color-printed images in Birds from Abroad: for example, in the deluxe finished book, the birds assume a variety of complex poses as they perch on flowering plants and trees.

How should these differences be accounted for? In the book’s front matter, Seki admits that a number of “not insignificant” changes to Shūsen’s source pictures took place in the course of their publication as a color woodblock-printed volume in Edo. First, the original life sized paintings were too large for convenient viewing, so Seki “hired an [artist]” to make smaller, more abbreviated paintings, which he collected into five volumes. Seki confesses:

I was able to gather several hundred species. Now, because I have taken these, reduced the size, and gathered them in this volume [Birds from Abroad], I fear that there are some significant differences between them [and the originals]. I only hope that the gist [of the work] has not been lost. It would be fortunate if viewers would infer the nature [of the originals from these pictures].[22]

In fact, Seki’s ornithological investment in the precision of both the names and forms of the foreign birds, as seen in his companion volume of text, is also what obliges him to eventually admit that the images printed in the book and drawn by Keisai differ significantly from the ones that he encountered in Nagasaki.[23] The foreword reads:

Beside these [birds] are placed strange cliffs, clear streams, flowers, trees, fragrant grasses, and so forth. This was not my original intent, but is only to assist in creating a mood: water was placed [in images] with mountain birds, and water birds were furnished with trees, and these are not necessarily things from over there [i.e. the depicted flora are not necessarily from the same native habitat as the birds]. I simply added things by eye. Viewers should pay it no heed.[24]

Far from being rare, the added flowers and trees are almost stereotypically familiar from Japanese painting: pine, cherry blossom, peony, iris, saxifrage (yukinoshita), small bindweed (hirugao), loquat, maple leaves, and camellia appear in seasonal order from winter through fall, and Seki confesses that their presence was an acquiescence for the creation of “mood” (omomuki 趣)—likely at the behest of the publisher, who needed to sell copies. Furthermore, the book of images was ultimately published and sold without Seki’s ornithological text, suggesting that the audience ultimately envisioned for the work was not necessarily a scholarly one.[25]

Art historians often discover that works previously treated as the “original” products of an individual artist actually resulted from the amalgamation of numerous precedents and prototypes. But in the case of Birds from Abroad, by contrast, rather than transmitting existing prototypes, Keisai appears to have completely reconceptualized the source drawings in the process of designing images for the deluxe woodblock-printed volume. He likely authored the images with the help of another trove of bird and flower pictures that the book does not credit.

Chinese and Japanese Image Compendia and Birds from Abroad

Detailed depictions of miscellaneous birds against a blank background have a venerable history in China and were widely circulated in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Japan.[26] While they bear the characteristics of sketches or preparatory drawings, some were made as connoisseurial items. A handscroll of birds by Ohara Keizan (小原慶山, d. 1733) in the Kobe City Museum employs silk and likely represents a connoisseur’s item that was made with documentary paintings of foreign birds as its basis (Fig. 12). Like Shūsen, Keizan had served the Nagasaki magistrate as a documenter of imports and appraiser of Chinese paintings. While this scroll at first appears very similar to the paper sketches of exotic birds sent to the shogunate, the pheasants and geese are instead depicted in elegantly paired or grouped poses that reflect the knowledge of courtly Chinese bird-and-flower paintings that arrived in Japan bearing the names of a range of masters, including the Qing painter Shen Nanpin 沈南蘋 (also known as Shen Quan 沈銓, 1682-1760), whom Keizan was privileged to meet during the former’s Nagasaki sojourn of 1731-33.[27] In Birds from Abroad, Keisai employed some of the same types of elegant Chinese-style poses, such as the depiction of a female goose or pheasant ensconced behind the male, but with heads pointing in different directions (Fig. 13). As an ukiyo-e artist and member of the artisanal class, Keisai must have gone out of his way to master these poses; in contrast to later artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige, there was no place among the existing woodblock print repertoire of the 1780s where Keisai could have gained easy exposure to them, and there were no public art collections in Edo.

Fig. 12. Detail of Ohara Keizan, Handscroll of Foreign Birds (Raikin zukan 来禽図巻), eighteenth century. Handscroll; ink and color on silk. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

Fig. 13. Keisai Kitao Masayoshi, “Silver pheasant (hakukan) and saxifrage (yukinoshita),” 1790-1791. From Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙). Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

In Birds from Abroad, the transformation from the Nagasaki “originals” to Keisai’s woodblock print designs was even more than a matter of elegant poses. According to Seki’s account in the front matter, it seems that the publisher set Keisai to the task of converting bird pictures into bird and flower pictures. Seki was never immune to the Nagasaki bird images’ aesthetic appeal, but the conversion effort that appears to have been initiated against his will undermined the natural history character of the project, and thus assimilated the book into the category of the woodblock-printed bird and flower compendia emphasizing aesthetic or poetic appreciation.

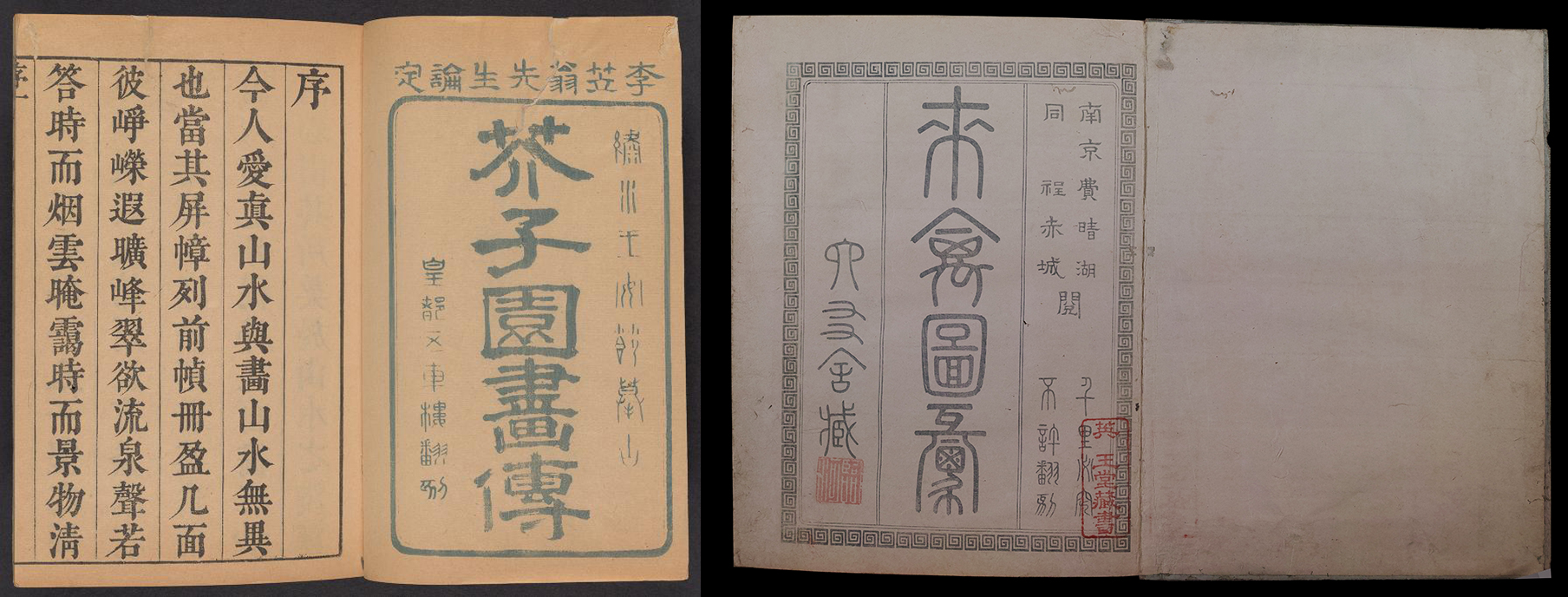

The foremost source for the endeavor of converting the paintings was the celebrated Chinese compendium, the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (Jieziyuan huazhuan 芥子園畫傳). In subtle contrast to Utamaro’s Myriad Birds, which employed crisp, black outlines, Seki and Keisai’s book emphasized “boneless” or unoutlined passages of delicately printed color. This approach evokes the third series (三集) of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, which also printed bird and flower scenes in delicate colors, without outlines (Figs. 14 and 15).[28] Compositional similarities are seen in the frontal or eye-level vantage points. The Mustard Seed Garden Manual portrays birds and flowers in a calm, uncluttered fashion, with ample blank space surrounding each pairing (compare Figs. 1 and 2). While some scholars have implied that few ukiyo-e print designers in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries would have had the chance to access this rare book, the assumption requires serious reevaluation, particularly for Keisai. Keisai was acquainted with members of Japan’s scientific community, particularly Morishima Chūryō (Nakara) 森島中良 (1756-1810), who was both a successful fiction author and a high-ranking samurai physician specializing in European medicine; his elder brother was one of the shogun’s doctors.[29] Morishima and the other scholars and scientists in his circle would have had access to many rare sources, both artistic and scientific, and it is through someone like Morishima that Keisai likely met the shogun’s chief councillor, Matsudaira Sadanobu 松平定信 (1759-1829), an avid patron of painting and literature.[30]

LEFT: Fig. 14. Wang Gai et al, Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, Third Series: Winged Creatures, Flowers, and Grasses (Jieziyuan hua zhuan sanji: Xiang mao hua hui pu 芥子園畫轉 三集 翔毛花卉譜 [1701]), 1812 reprint. Color woodblock-printed book. Harvard-Yenching Library.

RIGHT: Fig. 15. Wang Gai et al, Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, Third Series: Winged Creatures, Flowers, and Grasses (Jieziyuan hua zhuan sanji 芥子園畫轉 三集 翔毛花卉譜 [1701]), 1812 reprint. Color woodblock-printed book. Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University.

LEFT: Fig. 16. Unknown Japanese artist and calligrapher after Wang Gai et. al., Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, 1748. Title page. Kyoto: Kanan Shirōemon. Courtesy of Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

RIGHT: Fig. 17. Title page, Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad (Kaihaku raikin zui 海舶来禽図彙), 1790-1791. Color woodblock-printed book. Kobe City Museum. Photo: © Kobe City Museum.

These features suggest that Keisai and the publisher Matsmoto Zenbe’e had the bird and flower images of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual in mind when they began the process of transforming Seki’s Nagasaki bird paintings into the deluxe publication known as the Illustrated Book of Birds from Abroad. By creating a serene arrangement of birds and flowers in each frame and printing areas of color without ink outlines, Keisai and the printers evoked Chinese bird and flower prints. These Chinese prints had little to do with the initial documentary bird images that Birds from Abroad purported to transmit in its pages. Instead, they helped perpetuate the general aura of Chineseness, novel realistic effects, and access to rare materials promised by the book’s title and preface. The realism of Birds from Abroad was in this sense mediated through the model of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual and other woodblock-printed books of birds and flowers that were circulating in Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka.

In Japan, even the genre of the color-printed bird and flower book was closely associated with the model of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual. By some accounts, the first fully color-printed image compendium in Japan has been described as a copy of the flower portions of the famous Chinese work. That book, Purple Inkstone of the Ming Court (Minchō shiken 明朝紫硯, 1746), bore sensitively color-printed and stenciled images that evoked the whimsical and relaxed Chinese genre of paintings of flowers, fruit, grasses, and insects casually brushed in a literati style.[32] The Purple Inkstone featured flowers, rocks, and insects in a similar Chinese style, and as in the Mustard Seed Garden Manual, Chinese poetry accompanied each picture.

While Chinese references are important in understanding the genesis of Birds from Abroad, Japanese models are instrumental as well.[33] The several volumes of image compendia executed by a Nagasaki-style painter from Edo, Sō Shiseki 宋紫石 (1715-86), were similarly trend-setting publications. Like the Mustard Seed Garden Manual, most of the Sō Shiseki images were black and white, but in some early editions, the birds and flowers were printed in color, with delicate yet somewhat imprecisely registered zones of unoutlined color.[34] More influential was a work by Keisai’s teacher, Kitao Shigemasa, who designed Index of Haikai Flowers and Grasses, 2 vols. (Sōka haikai na no shiori 草花俳諧名知折, 1781) to accompany haikai poetry. This book, published in Edo in black and white with a limited number of printed instructions for color application, is in turn thought to draw on an Osaka flower book known as the Picture Book of Grasses of the Fields and Mountains, 5 vols. (Ehon noyamagusa 絵本野山草, 1755) by Tachibana Yasukuni 橘保国 (1715-92).[35] The bold, frontal close-ups of lilies, irises, chrysanthemums, and other common flowers were likely created with the needs of textile designers in mind.[36]

The second volume of the Ehon noyamagusa contains fluidly drawn, detailed images of birds, insects, and other animals. Through their confident, unfettered outlines and use of a daringly close, eye-level vantage point not seen in Chinese prints, they established the immediacy and vitality for which the birds and flowers of Keisai, Utamaro, and Hokusai would all later be known. The Index of Haikai Flowers and Grasses makes viewers feel as if they are crouching in a garden, their faces just inches from the blooms. The plants emerge from the lower margin, without the buffer of white seen in the Mustard Seed Garden images, and the exuberantly drawn plants thrust upward toward the top of the picture plane. Shigemasa, the author of these images, was also Keisai’s teacher, a fact that illuminates the otherwise uncharacteristic choice of the young Keisai for the Birds from Abroad project.[37]

As we have seen, Birds from Abroad began with the decision to publish a group of rare, lifelike paintings of exotic birds and ornithological data from Nagasaki. In the course of realizing that idea in the form of a commercially available, exquisitely color-printed book in the shogunal capital of Edo, the publisher and artist made drastic changes, such as the addition of ornamental plant life and the fabrication of elaborate poses and vantage points. Rather than faithfully transmitting one set of source paintings from Nagasaki, as announced in the preface, the resulting book mediated the real exotic birds documented in Seki’s severed text manuscript through multiple sets of source images: the highly detailed paintings of live birds that Seki saw, the stylishly Chinese images in the Mustard Seed Garden Manual, and Japanese illustrated poetry books such as Shigemasa’s Index of Haikai Flowers and Grasses. Even as these updates propelled Birds from Abroad away from Seki’s original scholarly intentions, they multiplied the textual and pictorial signifiers of Ming-Qing culture and helped to insert the finished product into the competitive and fast-paced environment of commercial publishing and bookselling in Edo. Appearing simultaneously with or within a year of Utamaro’s Myriad Birds (Fig. 15), Birds from Abroad presented an interesting rejoinder to Utamaro, emphasizing exoticism in contrast to the Myriad Birds’ focus on the birds, flowers, and poetry of “our country Japan.”[38] The successful insertion of Birds from Abroad into the market of color-printed books is suggested by the fact that about fifteen years later, an Edo publisher introduced another color-printed bird book by Keisai’s teacher Shigemasa, the Pictures of Birds Drawn from Life (Kachō shashin zui 花鳥写真図彙, 3 vols; 1805-1827). This book, which was printed in at least two stages, reflected the expansion of the market for bird and flower books, but it lacked the foreign cachet of Birds from Abroad, and surviving copies are printed in the crisply outlined Edo style of ukiyo-e printing, a far cry from the unoutlined “Chinese-style” color effects seen in early editions of Keisai’s Birds from Abroad.

The Border-Crossing Visual Data of the Global Eighteenth Century

The story of Birds from Abroad concerns the movement of visual data, not only from China, Europe, or Jakarta into Japan, but also from the trade port of Nagasaki to the shogunal capital of Edo. In this world, the pictorial output of artists and patrons was driven by the access to and demand for various sorts of information. That demand, and the strategies of satisfying it by a combination of actual specimens (or commodities) and of visual and textual depictions of specimens, was ultimately the same regardless of whether modern scholars might classify the information as artistic (e.g. Ming-Qing Chinese-style bird and flower paintings and prints) or scientific (e.g. rare birds). The right to see, use, and publish rare visual information was regulated by legal means and social conventions. But local conventions were also in the process of being relativized: in a globe that was being measured and quantified according to mercantile and imperialist ambitions, scientists and rulers discovered that natural history images held an exchange currency that relied on standardization. Natural history pictures of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries began to exhibit greater homogeneity throughout the world, including places where colonial occupiers trained local artists to depict flora and fauna. Strategies of verisimilitude and scientific accuracy were central to the appeal of Ming and Qing books and pictures in eighteenth-century Japan. Publishing and trade ensured that some readers gained access to a previously unthinkable quantity and variety of information.

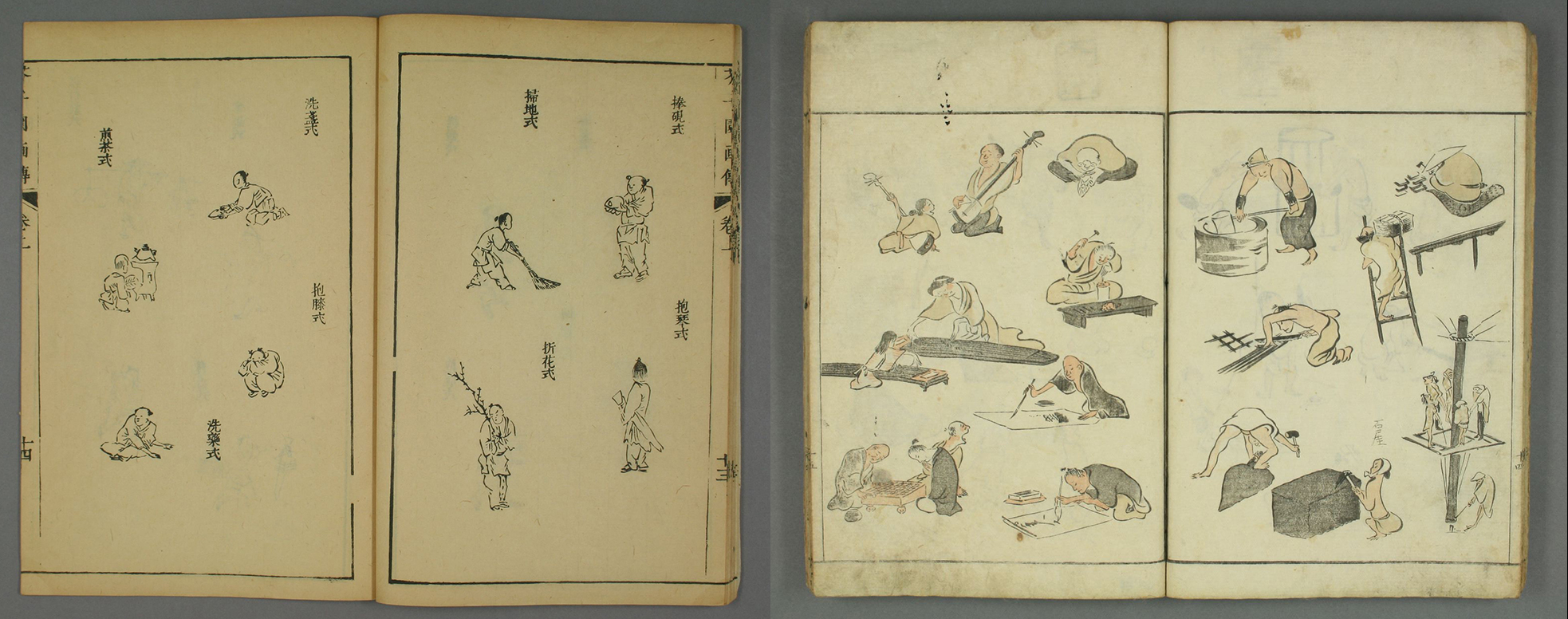

Although the Mustard Seed Garden Manual did not emphasize scientific accuracy in representation, as a book brimming with visual information, it became an important source for Keisai well beyond the successful publication of Birds from Abroad. The “abbreviated style” (xie yi 寫意) section of the Manual appears to have been one source of the pictorial strategy that Keisai would pioneer in 1795 with his Abbreviated Painting Types (Ryakugashiki 略画式) (Figs. 18 and 19). This book helped Keisai to launch his career as a purveyor of up-to-date Japanese painting manuals that predated the Hokusai Manga (Comic sketches, volume 1; 1814). Keisai’s shift away from the illustration of fiction and toward the sale of visual information in the form of painting manuals was politically and economically motivated. The inauguration of the Kansei era in 1789 and the appointment of Matsudaira Sadanobu as the top shogunal official was accompanied by a crackdown on satirical fiction of the type that Keisai used to illustrate. Shortly thereafter, Keisai earned a new position as a painter-in-waiting to the daimyō (feudal lord) of Tsuyama, who was also a member of the Matsudaira family.[39] Keisai’s new position, which carried samurai status, made it impractical for him to continue designing satirical kibyōshi book illustrations, but Keisai likely remained in need of income from book illustration.[40] The Mustard Seed Garden Manual and the experience of publishing the deluxe Birds from Abroad provided models for how Keisai could shift his involvement from fiction to the design of informational woodblock-printed books.

LEFT: Fig. 18. Wang Gai et al, Ji xie yi renwu shi極寫意人物式 (Transmitting the idea: Abbreviated Figures), Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (Jieziyuan hua zhuan, 1679-1701). 1817 reprint. Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University.

RIGHT: Fig. 19. Keisai Kitao Masayoshi, Abbreviated Painting Types (Ryakuga shiki 略画式), 1795. Edo: Suharaya Ichibē. Color woodblock-printed book (undated imprint). Waseda University Library.

Keisai’s works appeared at a moment in which woodblock-printed encyclopedias, painting compendia, and scientific images from Japan, China, and Europe were multiplying in availability.[41] His works, including Birds from Abroad and Abbreviated Painting Types, aggregate visual data and span multiple formats, such as books, single-sheet prints, hanging scrolls, handscrolls, and screens.[42] The important aggregating functions of his works were previously overlooked within an art historical environment whose disciplinary priorities continued to tend toward Romantic notions of artistic originality. The case of Birds from Abroad reminds us that for Keisai and his contemporaries, there was no necessary tension between the book’s purported transmission of (pictures of) real birds from abroad, and the fact that this transmission was mediated through the bird and flower prints of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual and through other Japanese and possibly Chinese sources. These unacknowledged sources added visual appeal, prestige, and commercial value to Seki’s initial undertaking. The finished product addressed a late-eighteenth-century desire for information and immediacy that cut across what are sometimes configured as the separate disciplines of art, science, and color printing technology.

Chelsea Foxwell is Associate Professor of Art History and the College at the University of Chicago

Appendix A

Chinese preface (excerpt), by Seki Mitsufumi

In our land, people are at peace and enjoy myriad pursuits. Here, international merchants bring strange and precious things: unusual birds and horses, trained beasts, and there is nothing that cannot be procured…In the Boshin year [probably 1788], when I went West in the service of the official retinue, among the many unusual things I saw during my official travels were new pictures of birds and animals. Each picture’s size was the same as the thing represented, and all depicted the truth. The colors of the feathers and fur, the sheen and brilliance: the ones with a tongue seemed as though they had a voice. The ones with wings outstretched seemed ready to depart. Comparing it with what I saw, there was not the least bit of difference or error. How skillful! The painting accordingly was of utmost mastery.

The birds pleased me, so I hired an artisan to wield his brush. The large [birds] were too large for the paper, and it would be difficult to roll and unroll the scroll. So I simplified (約) and made them smaller and collected and compiled them into a five-volume set. The names of the things depicted were all conferred by Qing or Western guests [in Japan].[43]

Appendix B

Japanese Foreword (excerpt)

1) All these pictures were offered to the Eastern capital. When I was in the [Nagasaki] outpost, I was fortunate to be able to see them.

2) Because they directly copy the truth, there is no question that the feathers, fur, and scales, the color and sheen are all [accurate]. Concerning the size, they are all the same as the thing [they represent], just as mentioned in the preface. The duplicates 副本, too, are guarded possessions of the artist. I was able to gather several hundred.

Acknowledgements: The author wishes to thank Ishizawa Shun, Katō Hiroko, Yung-ti Li, Yin Cai, Kristina Kleutghen, and the anonymous reviewers for their advice and assistance.

[1] Lafcadio Hearn, “Of the Eternal Feminine,” The Atlantic Monthly LXXII (December 1893), 77.

[2] Caroline Grigson, Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016); Louise E. Robbins, Elephant Slaves and Pampered Parrots: Exotic Animals in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002); Isono Naohide and Uchida Yasuo, Hakubutsu zufu raiburarii 5. Hakurai chōju zushi (Tokyo: Yasaka Shoten, 1992); Lai Yu-chih, “Images, Knowledge, and Empire: Depicting Cassowaries at the Qing Court,” trans. Philip Hand, Transcultural Studies 1 (2013), 7-98.

[3] Jennifer Roberts, Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); Daniela Bleichmar, Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

[4] The artist who began his career as Kitao Masayoshi later changed his name to Kuwagata Keisai after becoming a painter in the service of Tsuyama domain. Birds from Abroad was produced before Keisai’s promotion and is signed “Keisai Kitao Masayoshi.” I have examined copies of Birds from Abroad at the Kobe City Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Copies are also held at the Chiba City Museum of Art and the British Museum. Asano Shūgō, “Raikin zui no shoshi,” Ukiyo-e geijutsu 108 (1993), 44-50.

[5] Roland Barthes, “The Reality Effect [1968],” from The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1986), 141-148.

[6] Kitao Shigemasa, Sōka haikai na no shiori 俳諧名の知織 (1781); Idem, Kachō shashin zui 3 vols (1805-1827). Imahashi Riko, Edo no kachōga: Hakubutsugaku o meguru bunka to sono hyōshō (Tokyo: Sukaidoa, 1996), 322-327. Suzuki Jun, “Kitao Shigemasa ga Kachō shashin zui kō: Ukiyo-eshi ni yoru kachō ehon no kokoromi,” Kagami 39 (March 2009), 83-118. The publication of color woodblock prints of bird and flower themes was also new at this time. For an overview of ukiyo-e birds and flowers, see Cynthea Bogel, “Introduction,” in Hiroshige: Birds and Flowers (New York: G. Braziller, 1988). One of the earliest known examples is Chōrui shasei ehon 鳥類写生絵本 (1787) listed in the manuscript Nihon mokuhan sashie honnendai jun mokuroku by Urushiyama Matajirō (Waseda University Library, Kotenseki Database), but no copies of this book have been located (Katō Hiroko, personal communication).

[7] There is a discrepancy in the calendrical characters used on various surviving versions of this book. The MFA Boston and Asano Shūgō’s “Version A” (private collection) incorrectly list the dates as hinoto tori 丁酉, while in the Kobe City Museum this reads correctly in both places as tsuchinoto tori 己酉.

[8] See Timon Screech, The Lens within the Heart: The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2002); Chiba-shi Bijutsukan, ed., Edo no ikoku shumi : Nanpin-fū dairyūkō : shinseiki, shisei shiko 80-shunen kinen (Chiba: Chiba-shi Bijutsukan, 2001); Christophe Marquet, “La réception au Japon des albums de peintures chinois (huapu) du XVIIe siècle,” in Histoire et civilisation du livre. Revue internationale 3, ed. Drege and Bussotti, eds. (Geneva: Droz, 2007), 91-133. Ōba Osamu, Books and Boats: Sino-Japanese Relations in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, trans. Joshua A. Fogel (Portland, ME: Merwyn Asia, 2012).

[9] Asano Shūgō, “Raikin zui no shoshi,” Ukiyo-e geijutsu 108 (1993), 44.

[10] For a comparative description and analysis of the processes of sketching from live and dead birds, see Katō Hiroko, “Noda Tōmin hitsu Chōrui shasei zu: Ogata Kōrin hitsu Chōrui shasei zu to no kankei,” Bijutsushi 162 (2007), 338-355.

[11] The blue-printed inside front cover can be seen in the Kobe City Museum of Art and the National Diet Library editions.

[12] See David Howell, “Territoriality and Collective Identity in Tokugawa Japan,” In Public Spheres and Collective Identities, ed. Shmuel Eisenstadt, Wolfgang Schluchter, and Bjorn Wittrock (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2001), 144-154; Peter F. Kornicki, “Manuscript, Not Print: Scribal Culture in the Edo Period,” Journal of Japanese Studies 32:1 (2006), 23-52; and Christophe Marquet, “Learning Painting in Books: Typology, Readership and Uses of Printed Painting Manuals During the Edo Period,” in Listen, Copy, Read: Popular Learning in Early Modern Japan, ed. Matthias Hayek and Annick Horiuchi (Boston: Brill, 2014), 319-368.

[13] Chelsea Foxwell, “The Painter and the Archive: Models for the Artist in Nineteenth-Century Japan,” in The Artist in Edo Japan (Studies in the History of Art, no. 80), ed. Yukio Lippit (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, forthcoming).

[14] Nakada Katsunosuke, Ehon no kenkyū (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppansha, 1950); Marquet, “La réception au Japon,” Idem, “Furansu kokuritsu toshokan shozō no Ōoka Shunboku Minchō shiken o megutte,” Ajia yūgaku 109 (2008), 86-103; “Ōta Takahiko, “Ōoka Shunboku ga kataru Edo chūki no bijutsu dōkō,” Bigaku geijutsugaku 17 (2001), 1-31; Idem, “Gafu ni yoru kaiga no manabi: Tachibana Morikuni to Ōoka Shunboku no gafu o chūshin ni shite,” Bijutsu fōramu 21, vol. 12 (2005), 122-128; Nakayama Sōta, “Ukiyo-eshi ni miru edehon riyō no ichi kōsatsu,” Higashi Ajia bunka kōshō kenkyū 5 (Feb. 2012), 389-405. Image rights were a concern: Shūchin gajō, which published a set of Kano Tan’yū’s reduced-scale sketches of Chinese and Japanese masterworks , deliberately removed Tan’yū’s original references to the works’ owners and deferred from attaching any artists’ names to the works (other than the names that Tan’yū himself appended to a portion of the works).

[15] For information on Fei, see Nagasaki Rekishi Bunka Hakubutsukan, ed., Kyūshū nanga no sekai ten: Nagasakihatsu Edo jidai no nyū āto (Nagasaki: Nagasaki Rekishi Bunka Hakubutsukan, 2006).

[16] Asano Shūgō, “Raikin zui no shoshi,” Ukiyo-e geijutsu 108 (1993), 44-50.

[17] Watanabe Shūjitsu, Nagasaki gajin den 長崎画人伝, reproduced in Nihon gadan taikei, vol. 3, ed. Sakazaki Shizuka (Tokyo: Mejiro Shoin, 1917), 1301.

[18] Isono and Uchida, Hakubutsu zufu raiburarii 5. Hakurai chōju zushi.

[19] Isono and Uchida, Hakubutsu zufu raiburarii 5. Hakurai chōju zushi.

[20] Kagesato Tetsurō, Kawahara Keiga to Nagasaki-ha. Nihon no bijutsu 329 (1993), 31.

[21] Federico Marcon, The Knowledge of Nature and the Nature of Knowledge in Early Modern Japan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

[22] The original text reads: 其副本モ亦皆画家ノ帳秘ナリ。余数百種ヲ輯メ得タリ。今コレヲ小ニシテ此巻ニ枚ルガ故ニ恐ラリハ小差ナキコトアタハズ。要トスル所太体ヲ失フ事ナカラント欲ス。覧ル者察セラレバ幸ナリ。

[23] Seki next notes that the names of all the birds in the book were appended by the Chinese and the Dutch. He transcribes these in kanji and phonetics (katakana) and is careful to note that even where the kanji used by the Chinese were also used to represent a certain type of bird in Japan, he adhered to the Chinese name and pronunciation without attempting to reconcile the fact that the same kanji characters might refer to different birds in Japan than in China (For example, the characters 黄鸝 are sometimes read as uguisu [warbler] in Japanese, but in this case they refer to a species called huangli in Chinese or kōri in Japanese).

[24] : 今図ノ傍ラニ奇崖清流花樹芳艸等ヲ施ス。本是意アルニ非ス。雅趣ヲモムキヲ助クルノミ山鳥エ水ヲアシライ水禽エ樹木ヲヱがリ及び必シモ彼方ノ物ヲ以テセズ。此際ノ物ヲ以テスルハ我ガ目スル所ニ従フナリ。覧者拘ハル事勿レ。

[25] For those who sought them, the text descriptions of each bird and its features were eventually published in roughly the same format and dimensions as the color-printed book of images. Seki Mitsufumi, Kaihaku raikin zui setsu (Text catalog of birds from abroad), c. 1793. A copy of this book is housed in the National Diet Library. It is interesting to note that Seki adapted his ornithological text to Keisai’s images, adding, for example, simple natural historical and poetic notes about the native Japanese trees and flowers included in the book.

[26] Katō, “Noda Tōmin hitsu.”

[27] Kobe City Museum online catalog, http://www.city.kobe.lg.jp/culture/culture/institution/museum/meihin_new/611.html (accessed July 1, 2017).

[28] Previous scholars, with the exception of Suzuki Jun and Chrisophe Marquet, barely mention to the Mustard Seed Garden Manual as a potential reference point for Japanese books in the late eighteenth century. Nakamachi Keiko, “Kaishien gaden no wakoku o megutte” and Sasaki Moritoshi, “Hokusai wa Kaishien gaden o mita ka,” Bensei tsūshin, no. 14. Tokushū: Kaishien gaden o megutte (2009), 4-6 and 7-9. See also Nakada Katsunosuke, Ehon no kenkyū (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppansha, 1950).

[29] The men’s relationship is substantiated by Keisai’s contribution of an illustration to Morishima’s Red-Haired Miscellany (Kōmō zatsuwa 紅毛雑話, 1787).

[30] Uchida Kanzō, “Kinsei kaigashi ni okeru Kuwagata Keisai,” in Kuwagata Keisai (Kitao Masayoshi) (Tokyo, Tsuyama: Ōta Kinen Bijutsukan, Tsuyamashi Kyōiku Iinkai, 2004).

[31] Manzōtei [Morishima Chūryō], “Hogu kago,” Nihon zuihitsu taisei, 2nd set, vol. 4, p. 661. The episode is also cited in Marquet, “La reception au Japon,” 100.

[32] Marquet, “Furansu kokuritsu toshokan.”

[33] As Marquet recounts, among the first Japanese artists to produce original image compendia were Tachibana Morikuni and Ooka Shunboku, Kano-school artists from the Osaka region. Marquet, “La réception.”

[34] Itō Shiori, “Edo jidai chūki gadan ni okeru Shin Nanpin no denban to juyō ni tsuite,” Kajima bijutsu kenkyū nenpō 22 (supplement), 59-62; Idem, commentary on an untitled gafu associated with Sō Shiseki, FSC-GR-780.547, https://pulverer.si.edu/node/540/title/1 (accessed on August 1, 2017).

[35] Imahashi, Edo no kachōga, 321-322.

[36] Suzuki, “Kitao Shigemasa ga Kachō shashin zui kō,” 96-99. Imahashi, 321-322, also notes the importance of Kaibara Ekiken’s Medicinal Herbs of Japan (Yamato honzō, 1709) in laying the foundation for Ehon noyamagusa and subsequent works.

[37] Almost fifteen years after the successful publication of Birds from Abroad, the senior Shigemasa saw the full-color publication of his own bird and flower compendium. The Kachō shashin zui. For details, see Suzuki, “Kitao Shigemasa.”

[38] Asano, Ukiyo-e meihin gyararī 6. Utamaro no fūryū (Tokyo, 2006), 58ff. For Utamaro’s books, see the Fitzwilliam Museum online exhibition and translation http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/gallery/utamaro/ (accessed October 18, 2017) as well as Shūgō Asano and Timothy Clark, The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro (London: British Museum Press, 1995); Julia Meech, Utamaro: A Chorus of Birds (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981). Utamaro’s Myriad Birds, although advertisements suggest that Myriad Birds had already been conceptualized when the Picture Book of Insects appeared two years earlier. Asano Shūgō, “Raikin zui no shoshi,” Ukiyo-e geijutsu 108 (1993), 44-50; Asano, Ukiyo-e meihin gyararī 6. Utamaro no fūryū (Tokyo: 2006), 58, 66.

[39] For an overview of Keisai’s career and employeers, see Uchida Kanzō, “Kinsei kaigashi ni okeru Kuwagata Keisai,” in Kuwagata Keisai (Kitao Masayoshi) (Tokyo, Tsuyama: Ōta Kinen Bijutsukan, Tsuyamashi Kyōiku Iinkai, 2004). On daimyo patronage of ukiyo-e, see Naitō Masato, Daimyō tachi ga medeta ippin, zeppin: Ukiyo-e sai hakken (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 2005), 159ff.

[40] While occupying this position, Keisai continued to live mainly in the city of Edo. In the Genroku era, 1698, Matsudaira Nobufumi松平 宣富 (1680-1721), the third son of the daimyo of Shirakawa, was enfeoffed as the first domain lord of Tsuyama, with a yield of ten koku. In 1794, upon the death of his father, the nine-year-old Matsudaira Yasuharu松平 康乂(1786-1805) became the sixth lord of Tsuyama; in the same year, Kitao Masayoshi (Keisai) was appointed as one of the domain’s painters in waiting. There is speculation that Yasuharu’s clansman Sadanobu had something to do with the appointment; Sadanobu wrote of his respect for Yasuchika (1753-1794) as a man of learning. Matsudaira Sadanobu, Uge no hitokoto 『宇下人言』:『人となり博学弁才無双、相学、天学 をなして高談をよろこぶ。いかがしけん、予をば至ってしたしみて、つねに来り訪ひ給ふ。相客あれば 来り給はず。これ又偉人なり。」

[41] Henry D. Smith II, “World Without Walls: Kuwagata Keisai’s Panoramic Vision of Japan,” in Japan and the World: Essays on Japanese History, ed. Bernstein and Fukui (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1988): 3-19; Idem, “Picturing Maps: The ‘Rare and Wondrous’ Bird’s Eye Views of Kuwagata Keisai,” in Cartographic Japan: A History in Maps, ed. Wigen, Sugimoto, and Karakas (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016): 93-97.

[42] Uchida, “Kinsei kaigashi ni okeru.”

[43] The original text can be viewed at http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/kaihaku-raikin-zui-illustrated-catalogue-of-birds-from-overseas-255827 (accessed October 18, 2017).

Cite this article as: Chelsea Foxwell, “Mediated Realism in Kuwagata Keisai’s Illustrated Book of Birds From Abroad,” Journal18, Issue 4 East-Southeast (Fall 2017), https://www.journal18.org/2232. DOI: 10.30610/4.2017.2

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.