Mark Ledbury

One of the many pleasures of the recent Hubert Robert exhibition[1] was to contemplate again that marvelous and mysterious series of paintings Robert devoted to the Grande Galerie at the Louvre. Historians since Marie-Catherine Sahut’s pioneering work have investigated in detail what might have inspired Robert’s imaginative engagement with this space and associated the painting now in the Louvre (Fig. 1) with the furthering of plans for the early museological project to create a public showcase for the royal collections of painting.[2]

Fig. 1. Hubert Robert, Projet d’aménagement de la Grande Galerie, c. 1786-9. Oil on Canvas, 46 x 55cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais/Stéphane Maréchalle. Image source: RmnGP www.images-art.fr.

This project began in the 1770s but was not realized in any form until 1799—when, after much delay and the last minute destructions of a Napoleonic banquet, the French and Flemish galleries opened, still lit from the grand side windows overlooking the Seine—and not realized in full until Charles Percier’s renovation in 1805 installed the favored zenithal lighting.[3] In the history of museology the ambitious transformation of this gallery has special status, as it prefigures the museological experience (suites of rooms dedicated to national schools) that would be familiar to visitors from the nineteenth century onwards and is enshrined in both museum organization and art history worldwide.

Recent commentary has not, however, tended to see Robert as a chronicler of early museography, preferring a deeper and more imaginative investigation of the artist as the creator of a complex, uchronic universe, his Louvre fantasies reflecting a no-place, or a utopian mixture of chronologies, drawing on contemporary writing, design and architecture as well as his deep knowledge of antiquity.[4] In what follows, I will argue that his focus on the Grande Galerie might at least to some extent be tethered to the very specific and long-running debate about the transformation of the specific space of the Galerie. In particular, I am going to explore in detail here a dissenting voice raised against the planned top-lit showcase by someone who, like Robert, lived and worked in the Louvre, a protest against the very “éclairage par la voûte” that Hubert Robert’s paintings highlight in various ways.

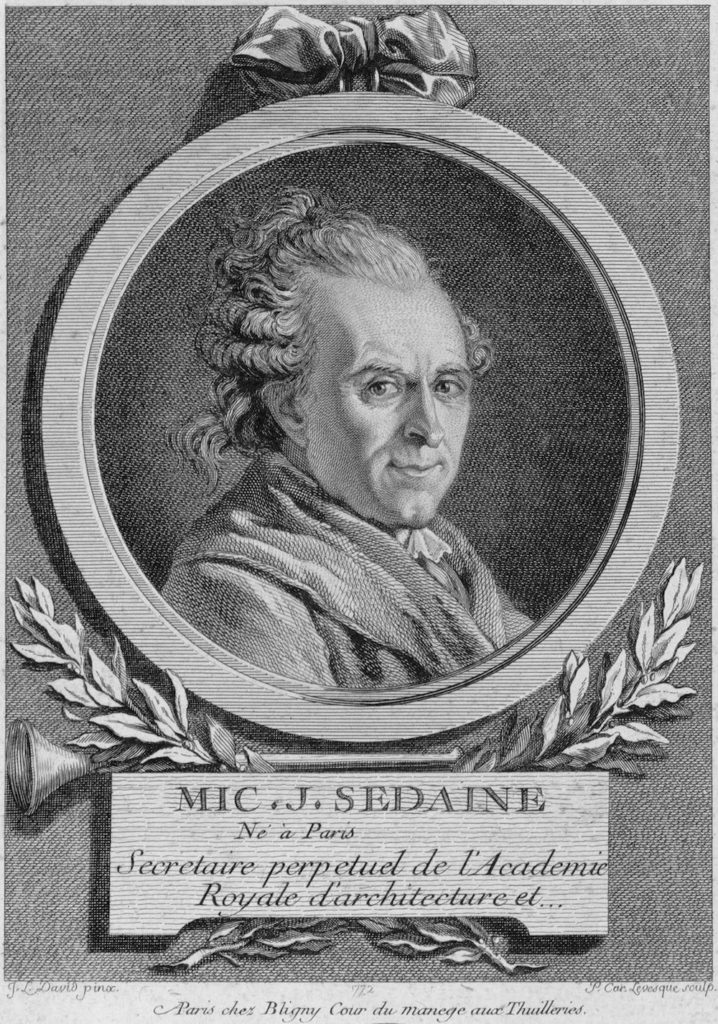

Fig. 2. Pierre-Charles Levesque (after Jacques-Louis David), Michel-Jean Sedaine, 1772. Engraving, 21.4 x 18.9 cm. École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Michel-Jean Sedaine’s post as secrétaire perpétuel of the Royal Academy of Architecture, to which he was unexpectedly appointed in 1768 and which extended until the end of the Academy itself in 1793, was an enormous honor and privilege (Fig. 2). One of its major benefits was an official apartment in the Louvre, and this situation ushered in a decisive and fertile period in the life of the dramatist, who united an inter-arts circle of wide-reaching importance, including Denis Diderot, Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, Augustin Pajou and the young Jacques-Louis David at his ample lodgings.

It was also for Sedaine an awkward and often disputatious period, a sometimes exquisitely miserable administrative incarceration in a world of tensions, debts, unpaid dues, dilapidated or otherwise unsuitable surroundings, rebellious behaviors, rivalries and the contempt of his peers, as my study of the procès-verbaux of the Academy and in particular the pièces annexes has revealed.[5] Sedaine grappled with a barely concealed contempt on the part of the court and of his own collègues in the Academy, who resented the imposition of an outsider and who bristled at their secretary’s lack of administrative tact, often awkwardly ethical stances and insistence on process. Consequently, the moments at which Sedaine’s own professional voice (that of his pragmatic experience in the company of the Burons, Desmaisons and the entrepreneurial building milieu in which he was raised, or of his fresher career as a highly successful playwright and a man of the theatre) was heard in the Academy were few and far between.

One such occasion, though, was during the extensive discussions in late 1785 and early 1786 of the renovations that were to transform the Grande Galerie (a central vestige of Henri IV’s Palace, and a highly visible link between the Louvre and the Tuileries palaces) into a suitable art-viewing space for the Royal collections. This project in embryo reached back as far as Joseph-Marie Terray and preoccupied imaginations in the Bâtiments du Roi through the later 1770s and 1780s.[6] The debate was reanimated with new enthusiasm, and the promise of funding, in the mid-1780s as the architects were directed to turn their specific attention to the practicalities.[7] One of the many substantive issues debated by the Architectes du Roi in the Académie in the course of their planning of the picture gallery in the Grande Galerie was the question of lighting. The vast majority of opinion on the part of royal architects and administrators, from Soufflot onwards, tended towards top-lighting the new art display space, which meant of course blocking up or otherwise darkening the grand windows that punctuated the elegant formal promenade leading from the Louvre to the Tuileries Palace on the side of the gallery overlooking the Seine. And indeed, the final decision for a top-lighting (éclairage par la voûte) solution was taken only after this period of debate in 1785-1786.

Sedaine’s intervention is virtually unknown, and yet of great interest. In its contrarian view of what the Louvre, and the Gallery, was and might be, it is full of insight into spectatorship and the haptic experience of the galleries of the Louvre that might strike a chord even with today’s visitors to the museum. The mémoire, though it might have its origins in debates from the 1770s, was, I believe, among the six opinions presented by academicians in the Grande Galerie itself, on February 13, 1786, in the heat of the deliberations and planning which had been kicked off at the behest of the Comte d’Angiviller in the preceding November.[8] Sedaine begins, as ever, defensively (and indeed this, and the fact that the mémoire is in Sedaine’s hand, is the best evidence of his authorship):

I will speak frankly in giving my opinion, animated only by the desire to contribute to the greater good of the matter, without claiming to give the best advice or aiming to contradict those who are in a far better position than I am to find and implement excellent solutions.” [9]

He then goes on to consider the implications of all the other plans produced by his fellow academicians, pointing out that they would be excessively costly and would entirely change the nature of the gallery and expose its structural weaknesses—the pediments, chimney-pieces and other key structures would be severely affected and most likely destroyed. He estimates it would cost at least 800,000 livres (a vast sum) and asks, spikily, “Who can give any assurance that, in France, a building project that will take at least four years, will ever actually get finished?” And, to make his point, he continues, “Where better to tell this plain truth than here in this endlessly unfinished Louvre?”[10]

Having opened in a confrontational mood, the mémoire adds a more philosophical tone as Sedaine warms to his key themes and gets beyond the extravagant cost and unrealistic timetable. He praises the rhythms of the Gallery as currently configured, a majestic connecting tissue between palaces, and then points out that this grandeur would be destroyed in the gloom of top-lighting. As he puts it, “This Gallery would then be nothing but a vast tomb” (cette galerie alors ne serait plus qu’un vaste tombeau), forbidding for women, children and the faint of heart, and oppressed by the somber and cloud-laden Parisian sky. And he asks, rhetorically, whether any of the masterpieces in the planned gallery could really compensate for having robbed the public of the “liveliest spectacle in the universe, the flowing Seine, the quays, the bridges, the sky stretching to the horizon, and the spectacle of the Parisian people.”[11]

In Sedaine’s heated rhetoric, top-light and side-light is a matter not just of light versus dark, but of life versus art, and even life versus death. Sedaine’s by then nearly two-decades as a Louvre-dweller seem to speak here, but so does his sensitivity to the public, to spectacle and to the experiential—a characteristic of his gifts as popular dramatist. Anticipating the counter-argument that the point of a visit to “this magnificent museum” (ce magnifique musée) would not be to see the outside view but rather to admire the paintings, he asserts, “of twenty thousand people who might come with this intention, there would not be more than a thousand who would spend even an hour in the space without getting bored, or needing some kind of distraction.”[12] His point goes to the heart of a still-live museological debate, as we consider the way in which the Louvre’s transformation into a twenty-first-century art museum (a work still not entirely finished!) has at key moments stressed top-light rather than side-light, the tomb rather than the passage; and as “museum fatigue” becomes a familiar term in guidebooks, scientific and popular culture.[13]

Beneath this concern for the visitor, I believe, lies a deeper one for the inhabitant of the Louvre. Sedaine’s plea for a habitable and human-friendly space, of course, was subtended by the fact that he, along with many friends and colleagues, including Hubert Robert, did actually live in the various floors of the galleries of the Louvre, and indeed, I think, this memoir might be seen as a prescient understanding of how the demands of museology would be at odds with those of artists, architects and artisans who had made the Louvre a special kind of dwelling place over the preceding decades. And of course, just as the Grande Galerie opened as a museological space (in its top-lit Percier-designed iteration) in 1805, so too commenced the final clear-out of artists from their studios and dwellings.

But Sedaine’s comments then return to the focus on conditions of viewing art. He asserts that, in fact, for the appreciation of art, ideal lighting is never the key issue. He uses the example of the exhibitions in the Salon carré:

Given that at the Salon we are presented, in that large space, with paintings lit from the side or indeed by direct facing light, has this prevented us from admiring that which was truly admirable? Has the public’s judgment ever been deceived by these conditions? Haven’t we in fact said, when discussing a painting disadvantaged by its placement there, “That’s a good painting, and it’s the work of a young man, it’s a shame that, as everywhere, seniority means precedence and pride of place;” but, for all that, the paintings have not suffered in our estimation.[14]

Sedaine’s faith in the public’s ability to supply its own light, so to speak, and to compensate for poor lighting and positioning, might not have been, in the end, a persuasive counter to the clearly prevailing mood among his architect colleagues in favor of top-lighting. But it is an interesting insight, I think, one that reflects Sedaine’s knowledge of artists and the nuances of Salon politics. And indeed Sedaine points out later that artists in their studios deal with side-light and rarely enjoy top-lit conditions as they make their art. Sedaine also marshals to his argument the experience of painters and amateurs in other places: first he notes the experience of artists and amateurs at the Palais Royal, where the enjoyment of the paintings was immense despite the “jour ingrat” (paltry daylight) in which they were seen, before going on to point to the specific and much-admired precedent of the Düsseldorf Gallery.[15] Sedaine’s examples were neither random, nor, perhaps, particularly welcome to his audience. The Orléans collection and its many admirers were a goad to the Bâtiments du Roi, and the Dusseldorf Gallery had presented a sophisticated museological model conspicuously not yet implemented in France.

This mémoire, then, is a plea for the “lived Louvre,” the Louvre of movement, air and light, the Gallery as a point of passage and spectacle linking life and art, a space of conversation and delight, and a last-ditch appeal against the dying of that light. It is also an assertion of the primacy of the public experience, of the need to understand, appreciate and nurture the sensibilities and intelligence of the new publics for art.

Sedaine’s appeal fell on deaf ears. We know that in March 1786, a series of decisions were minuted in the academy confirming not only the top-lighting of the new Gallery, but also the specifics of the project.[16] However, Sedaine’s prediction of cost overruns and eternal delays were indeed prescient, given that it would take nearly two decades to create the top-lit space as imagined in 1786. And these two decades are bookends for Hubert Robert’s series of painted meditations on the Grande Galerie. We don’t know whether Robert knew of Sedaine’s dissenting views of the fate of the Gallery, but the two men had many mutual friends including Charles de Wailly, Augustin Pajou (both of whom had been charged with working on the Grande Galerie project from 1778) and Jacques-Louis David, so it is very likely that the tensions of this debate were known to him. I would even argue that Sedaine’s sense of all that risked being destroyed by knocking a hole in the top of the gallery and destroying its architectural character finds its echo in the specifics of Robert’s Imaginary View of the Grande Galerie in Ruins (Fig. 3), one of the two imagined visions of the space that Robert exhibited in 1796, ten years after the debate.

Fig. 3. Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of the Grande Galerie du Louvre in Ruins, 1796. Oil on canvas, 115 x 145 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais/Jean-Gilles Berizzi. Image source: RmnGP www.images-art.fr.

We note in this picture, among the signs of destruction, destroyed pediments and chimney-pieces, blocked-up windows, and a gaping roof hole that casts gloom rather than light. This painting is much more frequently seen in terms of Robert’s complex understanding of the valence of the ruin, yet it also surely hints strongly, poetically, at the real sense of loss resulting from the proposed changes to the Gallery that Sedaine’s text so bluntly evokes. And in this context, let us compare to this dramatic destruction the small-scale painting of The Grande Galerie between 1801 and 1805 in the Louvre (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Hubert Robert, The Grande Galerie, between 1801 and 1805. Oil on Canvas, 37 x 43 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais/Jean-Gilles Berizzi. Image source: RmnGP www.images-art.fr.

For me, this is an interesting imaginative pendant to the famous 1796 Salon scene of ruin. This small painting shows a laterally-lit gallery in which, in the imposing passage-space, a draftsman contemplates a sculpture, mixed-sex couples admire paintings while promenading, and a benign, if “incorrect” light illuminates a grand yet intimate scene. The roof remains intact, the windows unblocked, and the enjoyment and appreciation of the paintings, as well as the activities of families, painters, connoisseurs and students, are bathed in the light of the city on the Seine. Might this elegant and eloquent painting stand as the last artistic testament to Sedaine’s suppressed vision of a grand and vibrant, if imperfectly lit space?

Mark Ledbury is Power Professor of Art History and Visual Culture and Director of the Power Institute at the University of Sydney

[1] Guillaume Faroult et al., Hubert Robert, 1733-1808: un peintre visionnaire – Paris, Musée du Louvre, 8 mars-30 mai 2016; Washington, National Gallery of Art, 26 juin-2 octobre 2016 (Paris: Somogy éditions d’art: Louvre éditions, 2016).

[2] Marie-Catherine Sahut, Le Louvre d’Hubert Robert (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1979).

[3] An early gathering of source texts for discussion of the Grande Galerie project is contained in C. Gabillot, Hubert Robert et son temps (Paris: Librairie de l’Art, 1895), 169-182. On the wider context of the transformation of the Louvre from the later eighteenth century, see Yveline Cantarel-Besson, La naissance du musée du Louvre: la politique muséologique sous la Révolution d’après les archives des musées nationaux (Paris: Ministère de la culture, Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1981); Andrew McClellan, Inventing the Louvre: Art, Politics, and the Origins of the Modern Museum in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Bette Wyn Oliver, From Royal to National: The Louvre Museum and the Bibliothèque Nationale (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2007); Johanne Lamoureux, “De la peinture de ruines à la ruine de la peinture. Hubert Robert et le Louvre,” Protée 27:3 (1999), 56-69.

[4] See for example, Nina Dubin, Futures and Ruins: Eighteenth-Century Paris and the Art of Hubert Robert (Los Angeles, Getty Publications, 2010); Paula Radisich, Painted Spaces of the Enlightenment (New York, Cambridge University Press, 1999); Hubert Robert: un peintre visionnaire (2016).

[5] See Mark Ledbury, Sedaine, Greuze and the Boundaries of Genre (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2000), chapters 7 and 9 for the conditions and difficulties during his appointment.

[6] Gabillot, Hubert Robert, 169-181.

[7] For the traces of this acceleration of urgency, see D’Angiviller’s letter to Mique (read in November 1785 to the Architectes du Roi and transcribed in Henry Lemonnier, Procès-verbaux de l’Académie Royale d’architecture 1671-1793, IX (1780-1793), 358-362), a document which captures a complex history of discussions between 1778 and 1785 around Soufflot’s and other plans for top-lighting the gallery and urges the Academy to make a collective and final decision to advise the King. The process of discussions is chronicled in Gabillot, Hubert Robert, 166-175.

[8] Sedaine’s memoir is among the papers of the Academies on deposit in the archives of the Institut de France (Archives de l’Institut, Pièces Annexes au Proces-Verbaux de l’Académie Royale d’Architecture, Carton B8), Document 1, Sedaine, “Réflexions sur La Grande Galerie” (hereafter, Sedaine, Réflexions).

[9] “Je dirai librement ce que je pense, je ne suis animé que du désir de contribuer au bien de la chose sans prétendre à conseiller le mieux, et encore moins à contredire ceux qui sont plus que moi en état de trouver et de faire exécuter d’excellents moyens.” Sedaine, Réflexions.

[10] “Qui peut assurer qu’en France un ouvrage qui ne pourra pas se terminer en moins de quatre années aura une fin? Où peut-on dire cette vérité si ce n’est dans le Louvre qui ne sera jamais fini?” Sedaine, Réflexions.

[11] “Sera-t-il dans cette galerie des tableaux, des chefs-d’œuvre, des prodiges en peinture dont l’aspect puisse faire pardonner d’avoir enlevé aux regards le spectacle le plus vivant qui soit dans l’univers, le cours de la Seine, les quais, les ponts, le ciel à l’horizon et la vue d’un peuple immense.” Sedaine, Réflexions.

[12] Sedaine, Réflexions.

[13] “Museum fatigue” was identified early in the twentieth century and continues to be discussed in scientific and museological literature. See for example, Benjamin Ives Gilman, “Museum Fatigue,” The Scientific Monthly 2, no. 1 (January 1916), 62-74; Stephen Bitgood, “Museum Fatigue: A Critical Review,” Visitor Studies 12:2 (September 2009), 93-111.

[14] “Puisque nous n’avons jamais vu de tableaux dans le jour le plus favorable et puisqu’au Sallon (sic) on ne nous a présentés dans un grand lieu que des tableaux éclairés de face ou de côté, avons nous cependant moins admiré ce qui était admirable? Le Public s’est il trompé de ce qui était bien? N’a t-on pas dit, sur les tableaux disgraciés par leur emplacement, “Voila un bon ouvrage, il est d’un jeune homme, c’est dommage que comme ailleurs, l’ancienneté ait donné des places, mais les ouvrages n’en ont pas été moins bien vus, et bien-jugés.” Sedaine, Réflexions.

[15] On the Düsseldorf Gallery, see Thomas Gaehtgens and Louis Marchesano, eds., Display and Art History: The Düsseldorf Gallery and its Catalogue (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2011).

[16] Though these were not officially minuted in the Procès-Verbaux, in Carton B8 of the Pièces Annexes is a report dated March 1786 on the final decision of the academy, among other things opting for top-lighting via the sommet of a vault rather than by sloped sides (flancs).

Cite this article as: Mark Ledbury, “Art versus Life: A Dissenting Voice in the Grande Galerie,” Journal18, Issue 2 Louvre Local (Fall 2016), https://www.journal18.org/866. DOI: 10.30610/2.2016.4

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.