Pierre-Édouard Latouche

Jean-François Bédard

In November 1894 an album of drawings of the Louvre was auctioned in Paris. It formed part of the vast collection of architectural documents assembled by the French architect, collector, and art historian Hippolyte Destailleur (1822-1893). The sale catalogue singled out the exceptional quality of this album, today in the collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA).[1] It contains some 120 drawings and engravings documenting the exterior and courtyard façades of the Louvre’s Cour Carrée. Different draftsmen and printmakers executed the images at various dates. The drawing style and the manuscript annotations suggest an execution between the 1750s and the late 1760s. Whoever assembled the album clearly wanted to document this specific moment in the Louvre’s history.

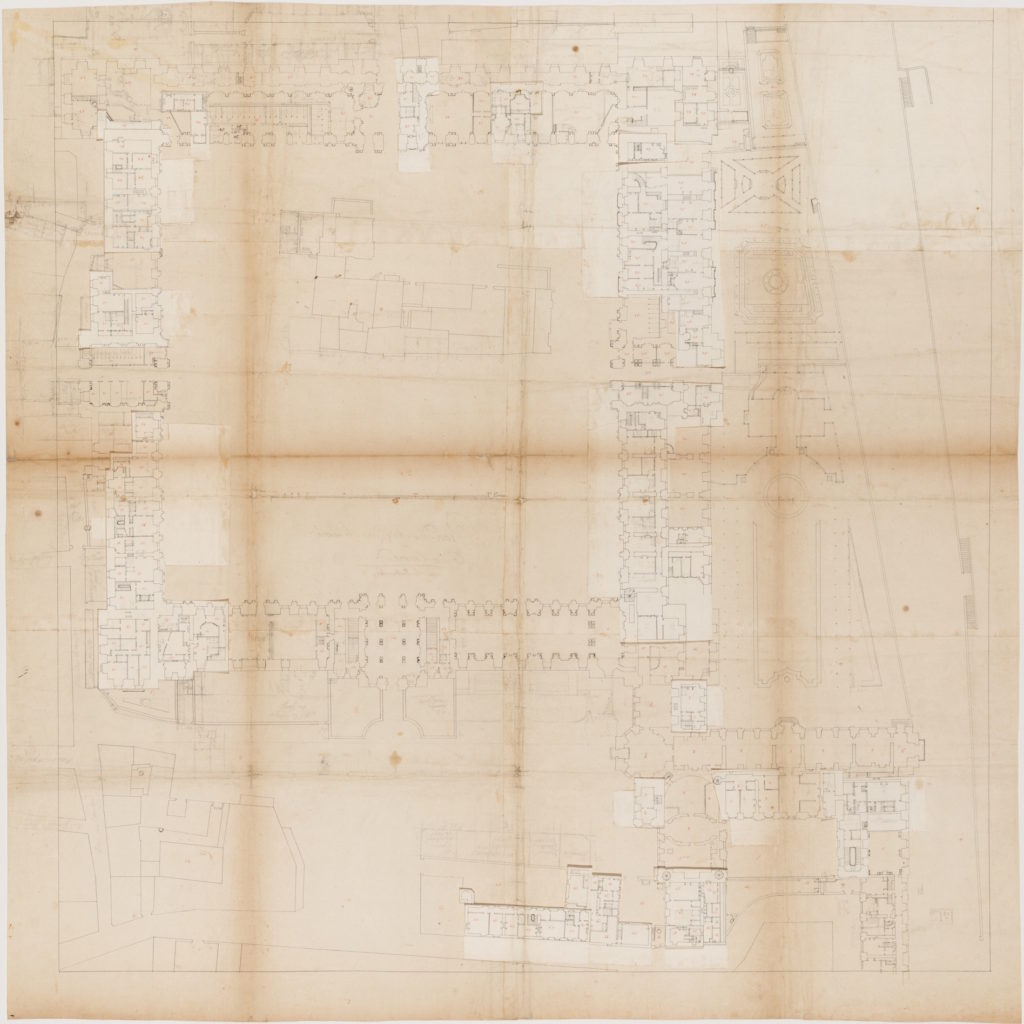

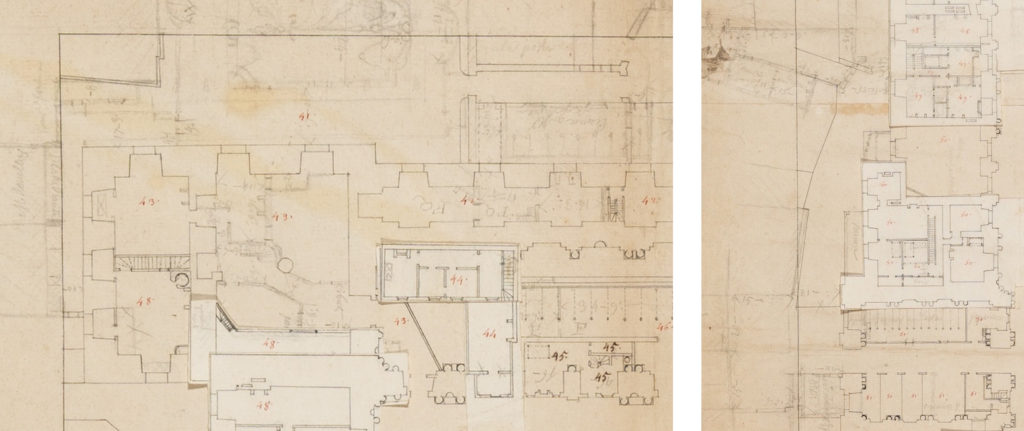

One of the most fascinating documents in this rich collection is an anonymous and undated plan of the ground floor of the Cour Carrée (henceforth the CCA plan; Fig. 1). This large sheet (92 x 92 cm), inscribed on the verso “Plan du Rez de chaussée du Louvre avec Les Entresols,” shows the layout of the four wings surrounding the courtyard and their interior distribution, which includes hundreds of rooms, cabinets, sculptors’ quarters and ateliers, and assorted service spaces such as stables, fountains, and latrines. The draftsman or draftsmen drew this plan in ink from observations and measurements taken on site and left a wide margin around it that is cropped at the top edge, probably when the album was assembled. Revisions and additions in graphite cover the drawing and its margins.

Fig.1. Plan of the ground floor of the Cour Carrée with mezzanines, ink and graphite additions on paper, 1745-1754. 92 x 92 cm. Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/ Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal. DR1986:0695:059.

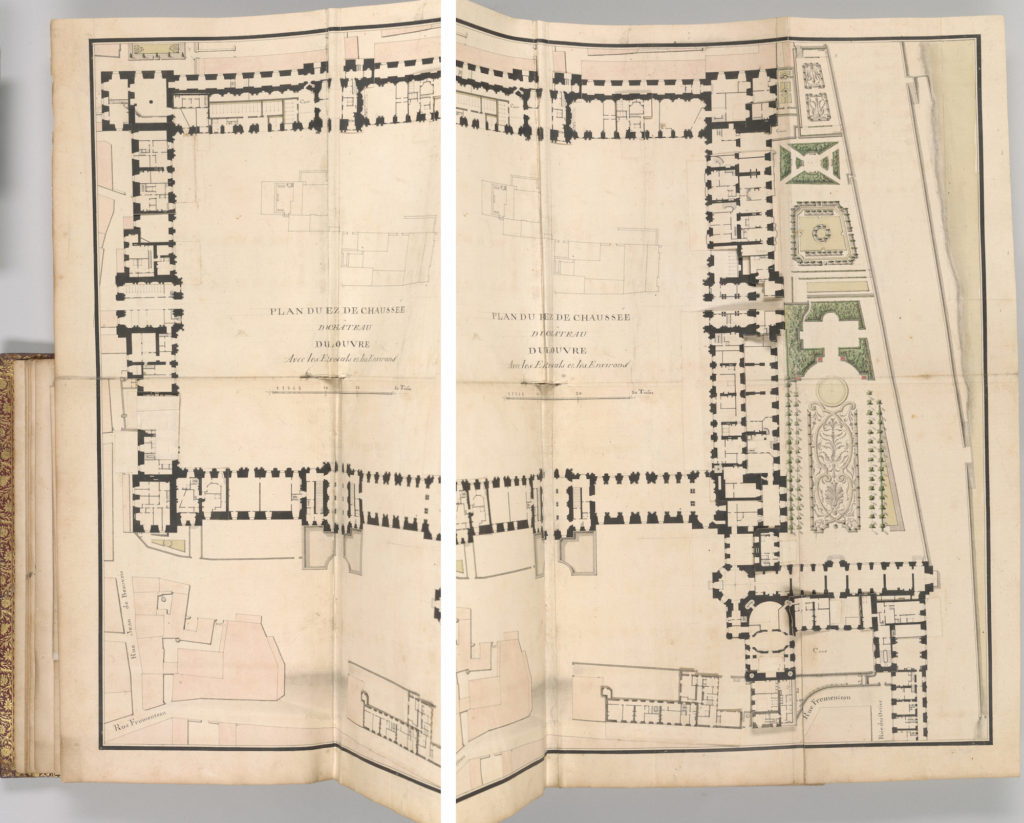

Recent studies have comprehensively documented the early history of this plan.[2] We know that it was initially commissioned as a preparatory drawing realized in late 1745 or early 1746 for the Recueil des Maisons Royales (1746-1751), a five-volume portable set of architectural plans of all royal properties. Charles Lenormant de Tournehem (1684-1751) commissioned the set to help him fulfill his administrative responsibilities as director of the Bâtiments du Roi beginning in 1746. Extant account books studied by Alden Gordon show that, at Lenormant’s request, the draftsman and painter Jacques-André Portail (1695-1759) set up a team of twenty surveyors and draftsmen to complete the Recueil.[3] Detailed entries in the account books describe how they drew plans in large format and then copied them at a smaller scale to fit the Recueil’s compact format. Included among the plans was one of the Cour Carrée’s ground floor. The same account books list payments made at each stage in the production of the Recueil. An entry identifies François de La Place as the surveyor of royal residences in Paris and the brothers Antoine-François and Maximilien Brébion as the draftsmen who, between January and March 1747, scaled down the drawings for the Recueil. A comparison between the plan of the Cour Carrée in Portail’s Recueil and the CCA plan confirms that the latter is the initial survey plan that the Brébion brothers reduced in scale: they reproduced every line of the CCA plan down to the smallest detail (Figs 2a and 2b).[4] The similarity extends to the numerous flaps affixed to both the Recueil plan and the CCA drawing, which depict the complex layers of entresols characteristic of artists’ quarters. The flaps show how one, two, sometimes three levels of entresols divided the lodgings horizontally.

Figs 2a and 2b. Antoine-François and Maximilien Brébion, Plan of the ground floor of the Cour Carrée with mezzanines, “Département de Paris: Recueil des plans du Palais des Thuilleries & des hotels qui en dépendent,” Plan 4, 1747. Ink and wash on paper, 52.5 x 52 cm. The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Mr. Junius S. Morgan and Mr. Henry S. Morgan. 1955.11.

Scholars, however, have not analyzed the plan beyond its initial commission and have not studied the revisions and additions in graphite. These revisions, which are extensive and methodical, document numerous but minor transformations in the interior distribution. Also present are spaces that are missing from the drawing’s first state, most importantly the city fabric surrounding the main portion of the palace, depicted in the margins. Far from being simply corrections to the initial plan, these additions resulted most probably from a new survey.

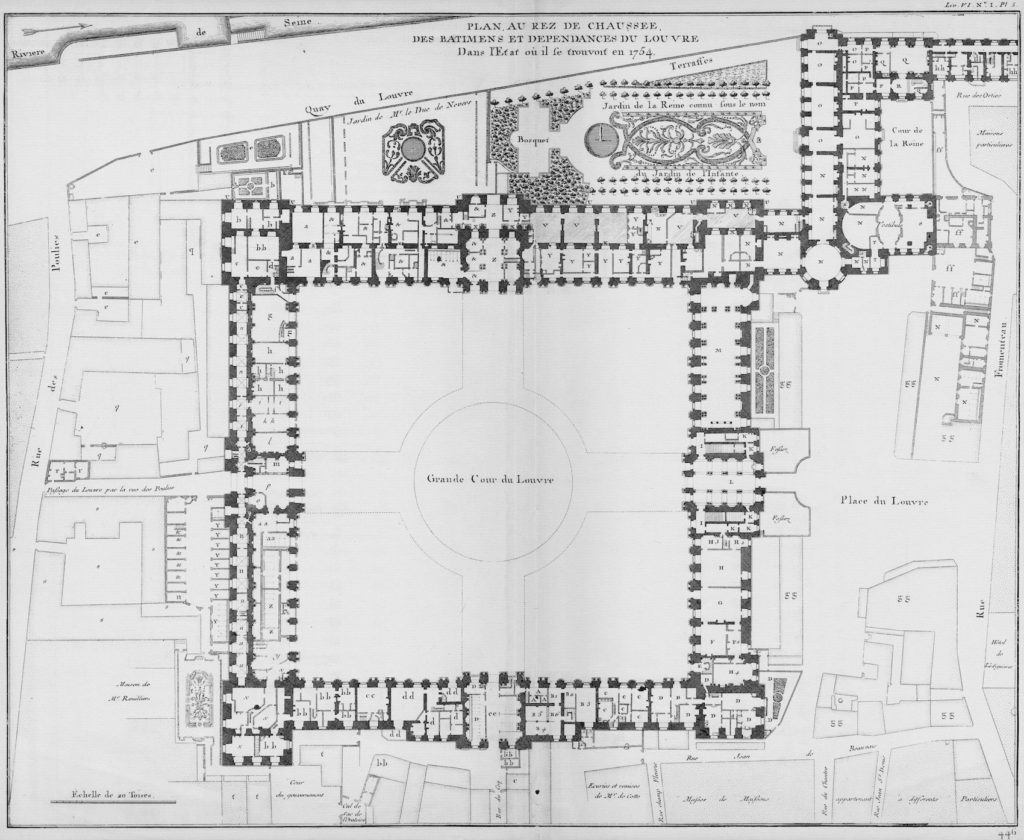

On the basis of the changes made to the CCA plan’s first state, this article argues that the educator and architect Jacques-François Blondel (1704-1775) sponsored this second survey as the basis for plate V of the fourth volume of the Architecture Française (Paris, 1756). Entitled “Plan au rez de chaussée des bâtimens et dépendances du Louvre dans l’état où il se trouvoit en 1754” (Fig. 3), this plate was part of a group of 110 new plates that Blondel commissioned to enhance a publication otherwise composed mostly of prints engraved by Jean Marot (1619-1779) in the seventeenth century and for Jean Mariette in 1727 and 1738 (see Appendix below).[5] As is well known, the imprimeur-libraire Charles-Antoine Jombert (1712-1784) acquired these plates from Mariette in 1750 and launched the Architecture Française project shortly after.[6]

Fig.3. “Plan au rez de chaussée des bâtimens et dépendances du Louvre dans l’état où ils se trouvent en 1754,” 1754. Etching on paper, published as plate V in Jacques-François Blondel, L’Architecture française, tome 4 (Paris: Jombert, 1752-1756). Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

To support the attribution of the updating of the CCA plan to Blondel, this article will take into consideration the corpus of newly-engraved plates commissioned for his description of the Louvre. The following pages will probe this small ensemble to determine how Blondel operated. We will propose that the coincidence between the preparation of volume four and contemporary debates on the restoration of the Louvre stimulated Blondel to describe the palace in detail, as attested by the elaborate survey he supervised. Blondel’s attention to contemporary architectural culture pushes for a reconsideration of the entire group of new plates for the Architecture Française, one that will provide fresh insights into Blondel’s critical contribution to this publication. Contrary to long-held views that see the Architecture Française as pivotal in Blondel’s “conservative turn,” one that resulted in the monumental, but aesthetically outmoded, Cours d’Architecture (1771-1777), this article argues that Blondel was in fact deeply engaged with the architecture of his day, including the dégagement of the Louvre. This casts a different light on the Architecture Française and makes it closer in spirit to the resolutely modern outlook of Blondel’s De la distribution des maisons de plaisance of 1737-1738. This close examination of Blondel’s strategy in the use of visual material for the Architecture Française will, therefore, contribute to broader studies on his entire theoretical position.[7] In addition, our reading of Blondel’s plan shows how, in the middle of the eighteenth century, the Louvre became the site of heated debates about royal architecture, as well as emergent notions of city planning, which played out not only in texts, but also in images.[8]

The illustrated description of the Louvre in the Architecture Française

Blondel completed the first part of volume four of the Architecture Française, which contains the description of the Louvre and the Tuileries, in July 1754. He finished the second part on Versailles by November 1755.[9] Censors approved the publication in March 1756. The in-folio distributed to subscribers shortly thereafter differed from what Jombert had promised in two successive prospectuses of 1751. The first of these, in March 1751, had announced the re-edition of the Architecture Française, whereas the second, a few months later, had informed readers that Blondel would write substantial descriptions of each building. Jombert initially planned twenty-one plans, sections, and elevations to illustrate the description of the Louvre. Among them, only two were to be newly engraved: plans of the ground floor and the first floor.[10] In its final form, four years later, the description featured nineteen illustrations that comprised six newly engraved plates.

Blondel eliminated miscellaneous images that, according to the prospectus, were to conclude the section on the Louvre. He removed a project by Cottard for a façade, two ceilings, a project for a grand staircase,[11] an elevation of the Galerie d’Apollon (in its state before the 1661 fire), and a spectacular elevation of the Galerie du bord de l’eau. He added plates to form a more coherent ensemble. He selected a reprinting of Le Vau’s south façade elevation and, most significantly, four new engravings showing overall plans of the palace. He moved the six new plans (including the two already announced in the prospectus) to the beginning of his description. In doing so, Blondel reversed the sequence Mariette had adopted for his own Architecture Françoise. Whereas the bookseller always began new segments with elevations and sections, Blondel privileged the building’s overall aspect over its parts.

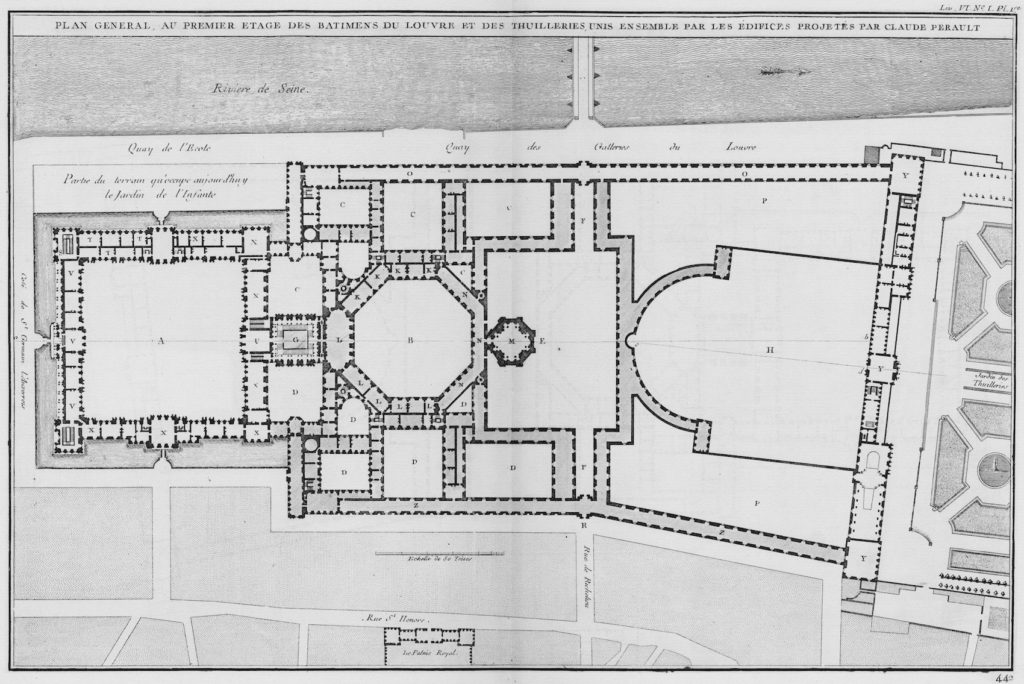

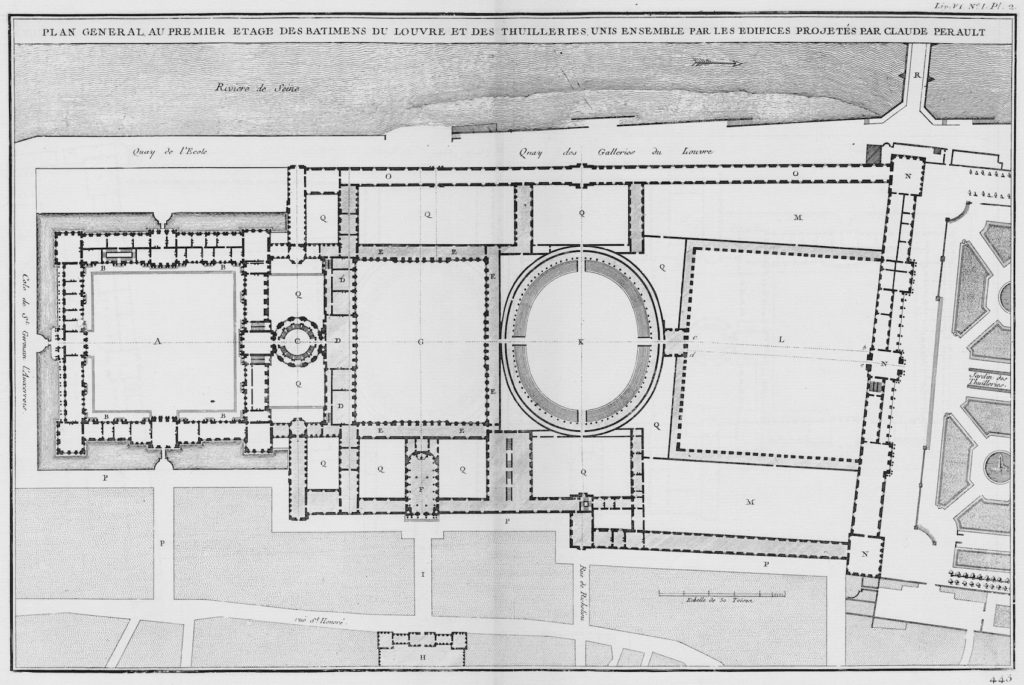

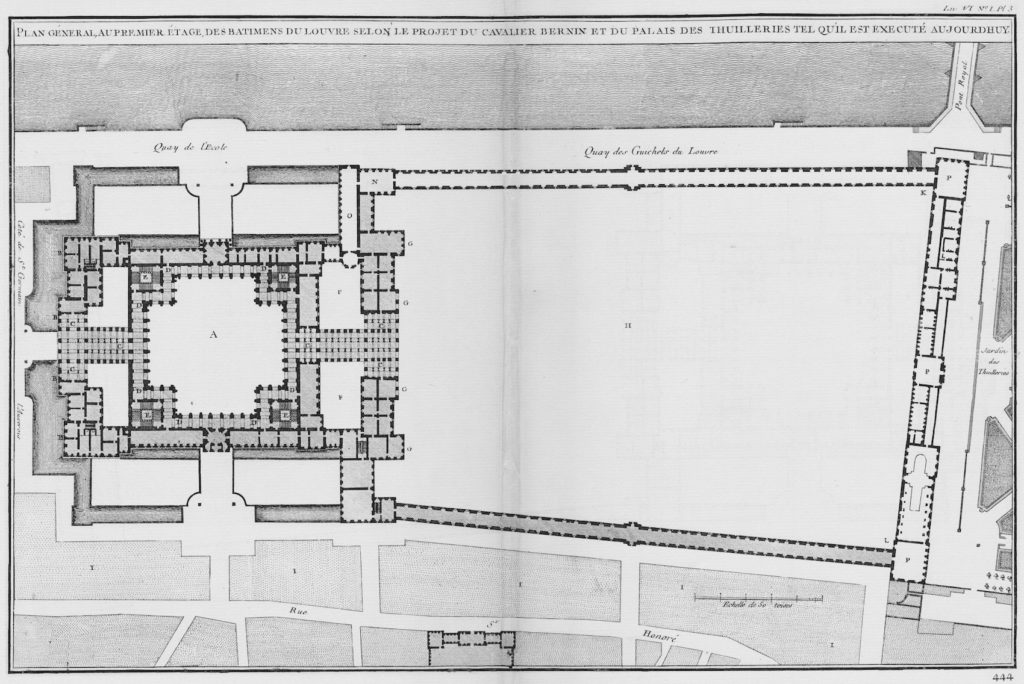

The first three site plans show schemes devised to unite the Louvre and the Tuileries. Plates I and II, represent plans by Claude Perrault (1613-1688). Both are entitled “Plan général, au premier étage, des batimens du Louvre et des Thuilleries, unis ensemble par les édifices projetés par Claude Perault” (Figs 4 and 5). The plan on plate III, entitled “Plan général, au premier étage, des batimens du Louvre selon le projet du cavalier Bernin et du palais des Thuilleries tel qu’il est executé aujourd’huy” (Fig. 6), illustrates one of Gianlorenzo Bernini’s celebrated proposals submitted to Louis XIV. Blondel selected Perrault’s and Bernini’s plans as models of expert planning. They show the Louvre and the Tuileries in one grand, regular ensemble. In all three instances, Blondel depicted the palace with the adjacent urban fabric as it stood in the 1660s. He did not think, however, that these designs were flawless. While Blondel appreciated Perrault’s multiplication of courts to hide the misalignment of the Louvre and the Tuileries, he nonetheless criticized their small dimensions, which made them, he believed, unsuited to a royal palace. However, he praised all three projects for their grandeur and particularly lauded Bernini’s scheme for its “essential beauties.”[12]

Fig.4. “Plan général, au premier étage, des bâtimens du Louvre et des Thuilleries, unis ensemble par les édifices projetés par Claude Perault,” 1754. Etching on paper, published as plate I in Jacques-François Blondel, L’Architecture française, tome 4 (Paris: Jombert, 1752-1756). Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Fig.5. “Plan général, au premier étage, des bâtimens du Louvre et des Thuilleries, unis ensemble par les édifices projetés par Claude Perault,” 1754. Etching on paper, published as plate II in Jacques-François Blondel, L’Architecture française, tome 4 (Paris: Jombert, 1752-1756). Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Fig.6. “Plan général, au premier étage, des bâtimens du Louvre selon le projet du cavalier Bernin et du palais des Thuilleries tel qu’il est executé aujourd’huy,” 1754. Etching on paper, published as plate III in Jacques-François Blondel, L’Architecture française, tome 4 (Paris: Jombert, 1752-1756). Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

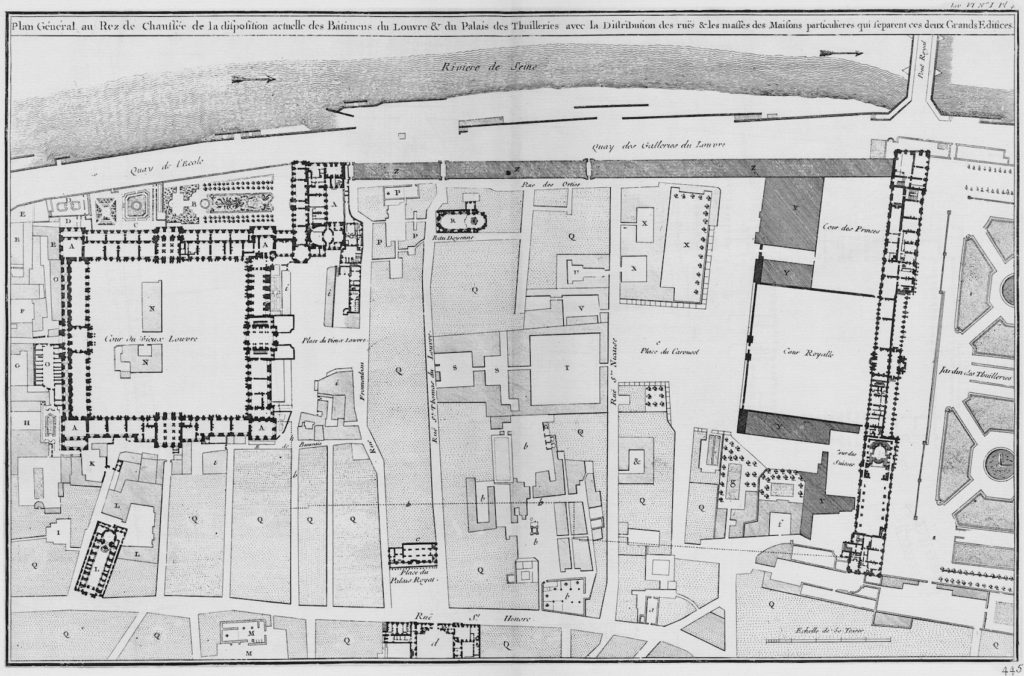

By contrast, Blondel used the next three plans, which show the Louvre and the Tuileries in their contemporary condition, as counter-examples of “abusive practices.”[13] Plate IV, entitled “Plan Général, au rez de Chaussée de la disposition actuelle des Bâtimens du Louvre & du Palais des Thuilleries avec la Distribution des rues & les masses des Maisons particulières qui séparent ces deux grands Edifices” (Fig. 7), shows both palaces as they stood in 1754, engulfed in a dense and irregular network of streets. This situation led Blondel to affirm famously that “l’on ne peut disconvenir aujourd’hui qu’il faille chercher le Louvre dans le Louvre même” (“it cannot be denied that, today, one must seek the Louvre in the Louvre itself”).[14] Blondel also criticized the royal administrators’ decision to allow the construction of important buildings next to the palace’s perimeter, since their future expropriation would be almost impossible.

Fig.7. “Plan Général, au rez de Chaussée de la disposition actuelle des Bâtimens du Louvre & du Palais des Thuilleries avec la Distribution des rues & les masses des Maisons particulières qui séparent ces deux grands Edifices,” c. 1754. Etching on paper, published as plate IV in Jacques-François Blondel, L’Architecture française, tome 4 (Paris: Jombert, 1752-1756). Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

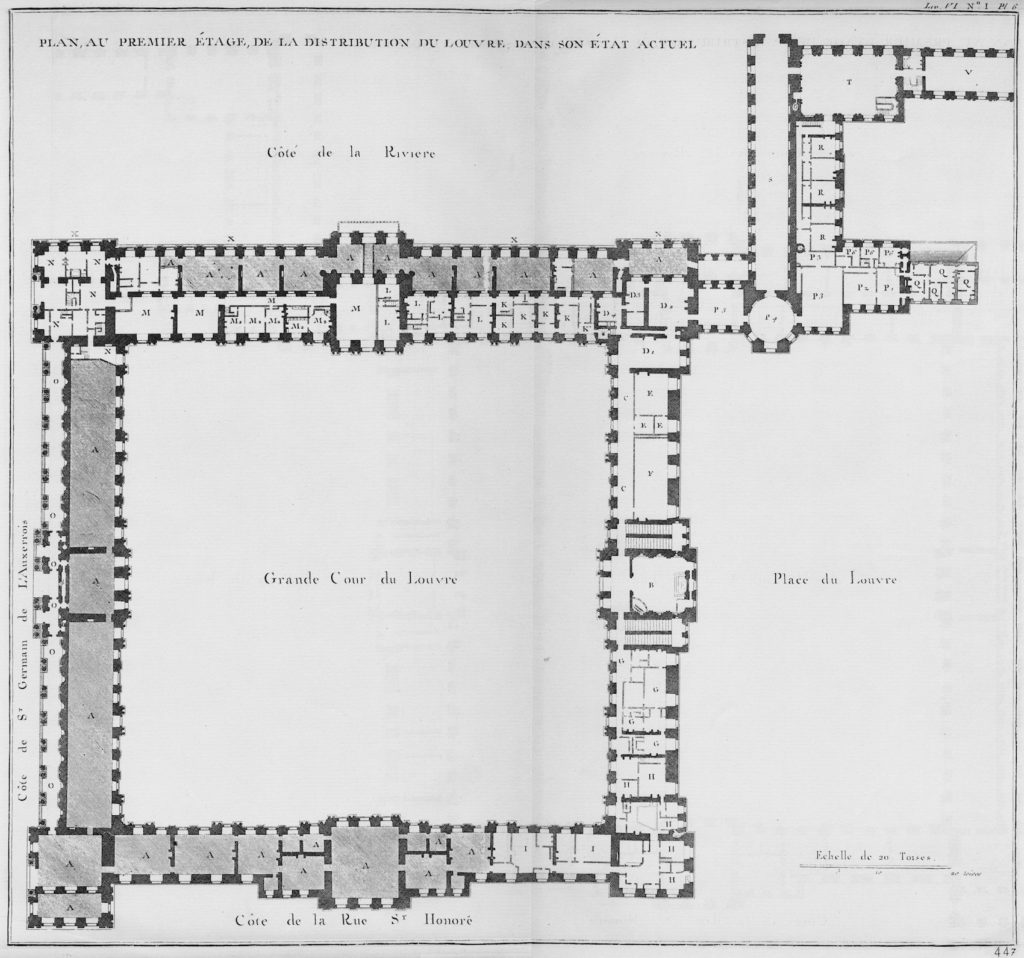

For the same reasons, Blondel condemned the state of the Cour Carrée as depicted in plans V and VI. Plan V, entitled “Plan, au rez de chaussée, des batimens et dependances du Louvre, dans l’état où il se trouvoit en 1754” (Fig. 3), focuses only on the Cour Carrée. It depicts the interior distribution of the Cour’s four wings and is accompanied by a key that identifies all their occupants, mostly sculptors. Blondel deplored the private and public constructions that blocked views of the east façade (Perrault’s Colonnade) and the north façade, two designs he highly admired. Plan VI, entitled “Plan au premier étage de la distribution du Louvre dans son état actuel,” illustrates the first-floor distribution (Fig. 8). Like Plan V, it features a key that lists its occupants, in this case mostly administrative departments.[15] With the help of these three plans, Blondel denounced the Louvre’s poor interior distribution and the urban encroachments on the palace, although he conceded that certain apartments were well distributed and decorated. Moreover, he believed that the Cour Carrée, even in its dilapidated state, was important because of the outstanding works of art that had been produced within its walls. He even called it a “sanctuaire des sciences, des arts et du goût” (“sanctuary of the sciences, the arts, and of taste.”)[16]

Fig.8. “Plan au premier étage de la distribution du Louvre dans son état actuel,” 1754. Etching on paper, published as plate VI in Jacques-François Blondel, L’Architecture française, tome 4 (Paris: Jombert, 1752-1756). Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

We must situate Blondel’s description and his reordering of the prints’ sequence, both devised to emphasize the building’s relationship to the city, in the context of contemporary debates on the dégagement of the Louvre. Ever since the competition for the Place Louis XV in 1748, the issue of the palace’s invisibility had been in the news. Several architects proposed to locate the future square between the Louvre and the church of St. Germain-l’Auxerrois to open up the view of Perrault’s Colonnade.[17] By 1749, when Étienne de La Font de Saint-Yenne published the Ombre du Grand Colbert, in which he pleaded for the restoration of Perrault’s façade, the polemical press had taken on the Louvre’s case.[18] During the 1740s and 1750s, critics ever more stridently urged the king to complete the Colonnade and launch other urban renewal projects in Paris that, they felt, the absentee monarchs had neglected.[19]

In 1753 Blondel himself joined the critics. In his text on the Bibliothèque Royale included in volume three of the Architecture Française, he bitterly deplored the lack of recent public buildings in the capital. He further complained that those edifices housing the major civic institutions were in urgent need of repair, and that others were impossible to see since “they were not made visible by avenues that would give a direct view to foreigners.”[20] It was against the backdrop of the polemics surrounding the Louvre’s dégagement that Blondel, in late 1753 or early 1754, decided to have original drawings engraved for his text on the palace.

In time, these debates led to the first great phase of restoration and completion of the Louvre’s Cour Carrée and the east façade of the palace, a project initiated by the Directeur des Bâtiments Abel Poisson, marquis de Marigny (1727-1781). The architects Ange-Jacques Gabriel (1698-1782) and Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713-1780) supervised the construction, in which the sculptor Guillaume II Coustou (1716-1777) took part. Work began in February 1755, when the Bâtiments demolished the houses within the Cour Carrée.[21] Remarkably, with his engraving completed by July 1754, Blondel anticipated the clearing. He published a plan showing the two paved and crossing alleyways that, to this day, divide the Cour Carrée into four smaller sections (Fig. 3). His prospective representation of the Cour, included on a plate that otherwise records exactly its contemporary state, attests to Blondel’s knowledge of the debates regarding the Louvre’s transformations. In a three-page Avertissement inserted at the beginning of volume four as it was made available to subscribers in April 1756, Blondel reflected on his prescience regarding the restoration campaign.[22]

The creation of the plates

To document his description of the Louvre, Blondel frequently visited the office of the Garde des plans des maisons royales located at Versailles, a service coincidentally headed by Portail since 1740.[23] There, Blondel selected plans to illustrate his text. Among the many architectural documents kept in this office, Blondel was especially interested in two albums of drawings and correspondence by Claude Perrault related to his projects for the Louvre, the Royal Observatory, and the Triumphal Arch of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. These albums were assembled in 1696.[24] They also included Charles Perrault’s important manuscript on his brother Claude’s work. Blondel quoted Charles Perrault abundantly in his description of the palace, his own text appearing often to be a commentary on Perrault’s manuscript.

In Portail’s office, Blondel uncovered Claude Perrault’s original plans and his variant schemes to link the Louvre to the Tuileries. These formed the basis of the two first illustrations (Figs 4 and 5).[25] For the third plate that showed Bernini’s proposal (Fig. 6), Blondel used a newly engraved version of Jean Marot’s plate, as specified in the prospectus. Issued in 1754, the new plate differs from the original in that it includes the Tuileries. In all three instances Blondel instructed engravers to shade Perrault and Bernini’s building additions to differentiate them from existing structures.

For plates IV, V, and VI, Blondel needed precise, recent surveys of the palace. He again found them in Portail’s office. The Garde des plans des maisons royales kept all materials produced by the Bâtiments, including the archives of the commission Portail had directed for Tournehem between 1746 and 1751.[26] The similarity between plate V (Fig. 3) and the CCA plan (Fig. 1) confirms that Blondel based his plate on the second survey.[27] It is likely that Blondel also commissioned the plan, as evidenced by its physical characteristics. The surveyors superimposed their additions in a sketchy manner, without the help of drawing instruments, as if they were revising Portail’s plan by carrying it from room to room (Fig. 9). The resulting drawing is similar to those made for engravings: it lacks the precision of drawings produced in an architect’s office. Absent from the second survey is a key listing the Cour’s residents, which Portail had provided on his original plan. Instead, the surveyors inscribed directly on the plan the names of the artists (“atelier de M. Bouchardon,” “atelier de M. Pigalle, sculpteur,” “atelier Slodtz,” etc.) next to their ateliers. The surveyors must have completed their revisions before mid-December 1754, since they included the name of the sculptor Jean-Joseph Vinache (1696-1754), who died on 14 December of that year.[28] This terminus ante quem agrees with the date in the title of Blondel’s plate.

The second surveying team recorded elements that are missing from the first state, most importantly the city fabric that surrounded the main portion of the palace, which they depicted in the margins (Fig. 10). Although Portail’s plan featured peripheral buildings, these were limited to the immediate footprint of the building. The second surveyors, by contrast, situated the palace in a much larger urban context as shown particularly in the left side of the CCA plan. Blondel also intended to include at the top edge of the drawing the buildings in front of the Colonnade towards St. Germain-l’Auxerrois. They appear today only partially because the top margin was cropped.

For plate VI documenting the plan of the first floor (Fig. 8), the engravers relied again on material found in Portail’s office. The title of plate VI specifies that it is represented “in its present state,” a fact that Blondel underscored in his description. Yet a few pages later he antedated the first floor’s distribution scheme to 1747. Because these rooms had changed so little since then, he explained, he did not think it was necessary to provide any more details.[29] Incidentally 1747 is also the year that Portail completed the Recueil on the Louvre.

Blondel’s illustrations before the description of the Louvre

Considering the importance of the Louvre, the changes it was undergoing in the mid-1750s, and the coincidence between its completion and the publication of volume four, it is understandable that Blondel attended particularly to the quality of his illustrations, as the updating of the CCA plan attests. His working methods and procedures had been tested in the previous three volumes that he had begun six years earlier. For the Louvre as elsewhere, Blondel added many more new plates which were announced in the prospectus. He particularly favored updated overall plans for which he relied on Portail’s documents. With the delivery of each new volume, the author adjusted the content according to the reception by the public.

As stated earlier, the libraire-imprimeur Jombert had launched the publication of the Architecture Française through subscription.[30] The practice of financing a publication by subscription originated in England at the end of the seventeenth century. This method reached France in the 1740s and 1750s, at the same time that Jombert began his project.[31] Libraires-imprimeurs would rely on subscriptions for very expensive publications, such as the in-folio Architecture Française and Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie. Using this system, they could ensure the sale of all copies. Consequently, prospectuses announcing new publications had to be as precise as possible.[32] Jombert’s Architecture Française prospectus of March 1751 is a model of the genre. It quantifies precisely every feature of the book: the number of volumes (eight in-folio), the number of plates (1400), the price for the eight volumes (360 livres on Grand Raisin paper, 460 livres on Grand Nom de Jésus paper), and the delivery dates.

Jombert was particularly prolix with respect to the relationship between the old and the new plates. According to the March 1751 prospectus, the first four in-folio volumes would have included 651 illustrations, 585 re-edited from Mariette’s plates and 66 newly engraved illustrations, which resulted in a total of 10% new images. [33] Only a short introductory text was promised for each building described. At 45 livres per volume, the Architecture Française was an expensive publication, considering that it was overwhelmingly composed of re-edited plates with little or no text.[34] As a comparison, Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, whose prospectus also came out in early 1751, featured eight in-folio volumes of text and two in-folio volumes that comprised 600 plates. The entire ten-volume set cost 280 livres, which amounted to 28 livres per volume. Jombert’s 1764 re-edition of the Petit Marot in 219 illustrations, albeit in a one-volume in-quarto edition, was even cheaper at 16 livres. Understandably, bibliophiles showed no interest in the initial Architecture Française.

During the summer, Jombert overhauled his project. In Fall 1751, he issued a new prospectus, the “Nouveau Programme.”[35] He announced to his readers that there would be substantially more text, written by Blondel, and additional new prints. The total number of images for the first four volumes jumped to 692, with 107 newly engraved illustrations (that is, 15% new images). He also changed the schedule for delivery of the eight volumes. Volumes one and two were to be delivered in April 1752, three and four in October 1752, five and six in April 1753, and seven and eight in October 1753.

Because Jombert’s archives are lost it is difficult to reconstruct the publication history between the “Nouveau Programme” and the delivery of volume four in 1756. Evidence exists, however, that the project faced significant problems. Every single volume was delivered late—three years in the case of the volume on the Louvre and the Tuileries—and, by the end of 1756, Jombert canceled the publication of the remaining four volumes without consulting Blondel.[36]

Jombert drastically adjusted the portfolio of illustrations that he had announced in his revised program at publication. He reduced the total number of images from 692 to 500. Significantly, 193 of the plates he chose to remove had been acquired from Mariette, while he barely increased the number of new plates from 109 to 110.

| March 1751 | Fall 1751 | As published | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume 1 | 168 | 178 | 136 (-23.5%) |

| Volume 2 | 158 | 158 | 109 (-31%) |

| Volume 3 | 192 | 194 | 107 (-45%) |

| Volume 4 | 65 | 65 | 38 (-41.5%) |

Jombert decided to get rid of some of Mariette’s plates incrementally, as he prepared and delivered each volume. As Table 1 shows, while he had initiated the attrition of re-edited plates in volume one and two, he increased it dramatically in volume three by cutting out nearly half of Mariette’s plates. In volume four, the newly engraved plates ended up forming a third of the volume, part of them in the description of the Louvre, as we outlined earlier.

Blondel’s candid comments shed light on the progressive elimination of Mariette’s plates from Jombert’s editorial project. Blondel explained that he suggested removing Mariette’s engravings because several readers had complained they depicted only old-fashioned buildings. Some critics even questioned why most of these buildings had been included in the book in the first place.[37] Blondel also mentioned that he discarded Marot’s plates because of their poor quality.[38] He believed in fact that Marot’s illustrations were the most problematic: not only, he explained, did the public think they were out of style; but also they had been badly engraved and subsequently overprinted. In his description of the Hôtel de Senonzan, Blondel apologized for relying on Marot’s plates despite their graphic shortcomings and their almost exclusive depiction of private houses.[39]

Thanks to his decision to increase the proportion of new plates, Jombert transformed his publication. Subscribers now received volumes with abundant text illustrated by many new images. The new iconography also shifted the Architecture Française’s focus. Among a total of 110 new plates, 52 show buildings, portions of buildings, and their interior distribution implemented during the last two decades, most of them since 1748. They show work that had just been completed or was still ongoing. The three plates of the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés document a project that had been begun by Boffrand in 1748 but was still unfinished, as was his Porte du cloître de Notre-Dame, whose construction had started in 1751.[40] The plate showing the interior layout of the Comédie-Française includes the modifications made to the orchestra pit in 1751. When new plates illustrate seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century architecture they focus on very recent additions. For instance, the ground-floor plan of the Hôtel de Maisons built by Lassurance in 1708 depicts the new interior planning completed by the architect Mouret in 1750.[41]

Besides the Louvre, Blondel was at his most exacting with the Palais-Royal in Paris and the Château de Versailles. In the first case, he deplored that he could not survey the palace because of ongoing construction, and was forced to rely instead on preexisting plans used for the palace’s remodeling. As for Versailles, featured in volume four distributed in April 1756, subscribers could examine its ground floor plan as it was in November 1755, a mere six months earlier. Blondel’s reliance on Portail’s survey of Paris completed in 1747 might also explain his emphasis on recent developments in architecture. As he did with the CCA plan, Blondel often completed or updated Portail’s plans through new surveys. For instance, in his description of the Château d’Eau, a large water reservoir located in front of the Palais-Royal, Blondel obtained the plans of the ground and first floors from Portail but had surveys done of the building’s elevation and sections.[42]

The CCA plan testifies to the importance Blondel placed on up-to-date illustrations in his writing of the Architecture Française. Dissatisfied with Jombert’s initial selection of outdated plates authored by Jean Marot and Jean Mariette, Blondel pushed for the engraving of recent buildings and for new surveys of existing ones such as the Louvre’s Cour Carrée recorded in the CCA plan. For these new images Blondel relied extensively on material he found in the archive of the Garde des plans des maisons royales, Jacques-André Portail. The type of documents Portail kept might indeed have guided Blondel’s editorial choices, as suggested by the inclusion of a plan of the manufacture des Gobelins, readily available in the Garde’s office, but otherwise of little architectural interest.[43] Beyond editorial opportunism, however, Blondel’s emphasis on sponsoring new images of recent buildings should make us reconsider his reputation as the anachronistic defender of the seventeenth-century Grand Manner in French architecture.

Pierre-Édouard Latouche is Professor at Université du Québec à Montréal

Jean-François Bédard is Associate Professor at Syracuse University

Appendix

It has been known for a long time that Blondel added new plates to the Architecture Française, but the extent of his contribution has always been underestimated. This is due in large part to André Mauban, who, in his 1944 monograph on Mariette’s Architecture Française of 1727 and 1738, dismissed Blondel’s additions as minor.[44] In the 1950s Emil Kaufmann, on the other hand, attributed to Blondel the authorship of most of the plates published by Mariette.[45] Although this thesis has been definitively disproved by a recent exhibition at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, which demonstrated that most of the plates were drawn by Jean-Michel Chevotet, the idea that Blondel was the author of Mariette’s plates had a lingering effect.[46] It led scholars to believe that, in the Architecture Française’s 1752-1756 edition, he limited himself to the addition of text to images he had produced previously. Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, in his introduction to the 2009 reprint of the Architecture Française, estimates the number of new plates at “slightly more than 80” but does not give a list of these or explain how he arrived at that number.[47] Aurélien Davrius, in his recent anthology of Blondel’s writings and conferences, repeats Montclos’s estimate.[48]

The table below details, for each volume, the 110 newly engraved plates. Plates are identified by the consecutive numbers Jombert gave them. Plate numbers are followed by notes justifying the attribution of the plate as new.

Abbreviations

PROS1 = Prospectus of March 1751

PROS2 = Second prospectus

BLON = Blondel with page in the corresponding volume of the Architecture Française

NIM = Plate not from Mariette’s fonds

PORTAIL = Plan present in Portail’s recueil

| Volume 1 16 plates |

1-8: PROS1; PROS2 / 19: NIM / 23: NIM / 38-39: PROS1; PROS2; BLON226 / 89: BLON257 / 93-94: PROS2 / 139: NIM |

| Volume 2 39 plates |

153-154: PROS2-BLON2 / 160: NIM / 161-166: PROS2 / 168: PROS1; PROS2 / 173-177: PORS2; BLON43 / 181:BLON52 / 183-184: BLON52; PROS1 / 189: BLON52; PROS2 / 191-192: PROS1 / 193: PROS1; PORTAIL / 209-212: PROS2 / 213-214: PROS2 / 220: PROS2; PORTAIL / 222-224: PROS1 / 225: PROS1; BLON107 / 229: BLON107 / 262: PROS2; BLON137 / 274: BLON144 / 282: PROS2 / 291-292: PROS2 |

| Volume 3 34 plates |

310-311: PROS2; BLON10 / 312-313: PROS2 / 319-321: NIM / 324: BLON27 / 332-335: PROS1; PROS2; BLON41 / 336-340: PROS2; PORTAIL / 346 – 347: BLOND55 / 351-354: PROS1 / 355-357: PROS2; PORTAIL / 384: BLON100 / 385: NIM / 407: BLON118 / 409-411: PROS1 / 426: BLON147 |

| Volume 4 21 plates |

442-447: PROS1; PROS2; PORTAIL; BLON10; BLON12; BLON15; BLON16; BLON39 / 461: PORTAIL / 463: BLON76 / 464: PROS1; PORTAIL / 475: BLON475; PORTAIL / 476: PORTAIL / 491-497: PROS1; PROS2 / 498-500: BLON153 |

[1] Collection Canadian Centre for Architecture, DR1986:0695:001-093. The sale catalogue describes the album as follows: “Détails du Palais du Louvre, dessins minutes par Le Dreux et Potain, 1749, in-fol., demi-rel., Recueil unique formé au commencement du siècle, probablement par un des architectes chargés de l’entretien et des réparations du Louvre. Il comprend une série de 60 dessins, soit de détails d’architecture, soit de plan généraux et détaillés du Louvre des plus importants pour l’étude de l’architecture de cet édifice. À ces dessins sont jointes 31 planches de vues d’ensemble ou de détails de ce monument et 18 planches de projets divers de Percier, Fontaine, Perrault, pour la réunion du Louvre aux Tuileries.” Catalogue de livres et estampes relatifs à l’histoire de la ville de Paris et de ses environs, provenant de la bibliothèque de feu M. Hippolyte Destailleur (Paris: D. Morgand, 1894), 53, no. 231.

[2] The basic chronology of this plan was presented in 2013 in an unpublished paper given by Pierre-Édouard Latouche at the Louvre before the Louvre conference at the Wallace collection in London. Since then, studies of the CCA plan have appeared in: Natasha C. Lee, “Scale Models and Stables: Form and Function in the Eighteenth-Century Louvre,’’ L’Esprit Créateur 54:2 (2014), 63-77; and Guillaume Fonkenell, “Les relevés du Louvre et des Tuileries sous l’ancien régime,” Livraisons d’histoire de l’architecture 30 (2015), 34-35.

[3] Alden Gordon, “Les Recueils des Maisons Royales en Petit and the Office of Jacques-André Portail, Garde des Plans des Bâtiments du Roi,” Eighteenth-Century Life 17:2 (May 1993), 102-45. We wish to thank Alden Gordon for his study of the drawing during a visit to the CCA in March 2006.

[4] Anonymous, “Département de Paris: Recüeil des plans du Palais des Thuilleries & des hotels qui en dépendent,” plan 4. The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, no. 1955.11. The Morgan owns a complete set of the Recueil. There is another set, incomplete, at the Archives nationales in Paris.

[5] On Marot see André Mauban, Jean Marot, architecte et graveur parisien (Paris: Les éditions d’Art et d’histoire, 1944); and André Mauban, L’Architecture Française de Jean Mariette (Paris: Van Oest, 1946). According to Kristina Deutsch, 79 plates are by Marot. See Kristina Deutsch, Jean Marot: Un graveur d’architecture à l’époque de Louis XIV (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2015), 39.

[6] Catherine Bousquet-Bressolier, “Charles-Antoine Jombert (1712-1784). Un libraire entre sciences et arts,” Bulletin du bibliophile 2 (1997), 312.

[7] Antoine Picon has advanced the idea that Blondel’s embracing of tradition was a piecemeal and hesitant affair, rather then a programmatic undertaking. Antoine Picon, Architectes et ingénieurs au siècle des Lumières (Paris: Éditions Parenthèses, 1988), 9. Since then, Edoardo Piccoli has convincingly developed the argument, pointing out that Blondel’s conversion to the Grand Goût only began to manifest itself in the fourth volume. See Edoardo Piccoli, ‘’L’antique pour un moderne,’’ Revue de l’art 170 (2000-2004), 78-79.

[8] See Richard Wittman, Architecture, Print Culture, and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century France (New York and London: Routledge, 2007).

[9] Blondel makes this clear in the Avertissement that was inserted in volume four just as it was being sent by Jombert to subscribers in April 1756. In it, the author reveals that the text and the plates were printed two years earlier, in July 1754, from proofs completed “longtemps auparavant” and apologizes for the delay. The date of November 1755 for the description of Versailles is given by Blondel. See Jacques-François Blondel, Architecture Françoise, ou Recueil Des Plans, Elevations, Coupes Et Profils Des Eglises, Maisons Royales, Palais, Hôtels & Edifices les plus considérables de Paris, ainsi que des Châteaux & Maisons de plaisance situés aux environs de cette Ville (Paris: Charles-Antoine Jombert, 1752-56), vol. 4, 113.

[10] “Architecture Françoise… Proposés Par Souscription” reproduced in Jacques-François Blondel, L’Architecture Française dite Le Très Grand Blondel (Paris: Éditions de l’Académie d’Architecture, 2009), I, n. p. The two prospectuses are included in this edition.

[11] Blondel states in a footnote that existing prints of this staircase had all disappeared. Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, (q).

[12] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, 15.

[13] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, 17.

[14] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, 17.

[15] Although the Architecture Française does not include an attic plan, the CCA album comprises a “Plan de l’attique avec les entresols” which, like the ground-floor plan, was commissioned by Tournehem and updated in graphite but never engraved.

[16] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, 39.

[17] André Chastel and Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, “L’aménagement de l’accès oriental du Louvre,” Monuments historiques de la France 12:3 (1966), 176-249, see esp. 190-92; Jörg Garms, Recueil Marigny: projets pour la place de la Concorde, 1753 (Paris: Paris Musées, 2002).

[18] [Étienne de La Font de Saint-Yenne], L’Ombre Du Grand Colbert, Le Louvre, Et La Ville De Paris. Dialogue (The Hague: 1749).

[19] Richard Wittman, “Architecture, Space, and Abstraction in the Eighteenth-Century French Public Sphere,” Representations 102:1 (Spring 2008), 9-10; Richard Wittman, “Politique et publications sur Paris au XVIIIe siècle,” Histoire Urbaine 1:24 (2009), 15-21.

[20] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 3, 69.

[21] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, iii. Edmond Jean François Barbier, Chronique de la régence et du règne de Louis XV (1718-1763), ou Journal de Barbier avocat au parlement de Paris (Paris: Charpentier, Libraire-Éditeur, 1857), 6, 131-33.

[22] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, iii.

[23] Blondel refers three times to Portail’s office, always in enthusiastic terms. Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, 4-5 (d); 6(9) and 100 (h). Claire Aubaret, “Les copistes du Cabinet des tableaux de la surintendance des Bâtiments du roi au XVIIIe siècle,” Bulletin du Centre de recherche du château de Versailles (18 December 2013) doi: 10.4000/crcv.12223. On the creation of architectural archives at Versailles see Gordon, “Recueils,” 123-127; and Deutsch, Jean Marot, 21.

[24] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, 4-5 (d); 6(9) and 100 (h). These two albums were lost when the Louvre’s library was destroyed by fire in 1871.

[25] “[L]e plan original, d’après lequel nous avons copié celui que nous offrons ici.” Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, 12.

[26] In his study of Portail’s Recueil, Alden Gordon found in a table of contents a reference to a plan of the Louvre and the Tuileries. Although this drawing is now missing, it most probably was the basis for plate IV. Gordon, “Recueils,” 142.

[27] It is unlikely that Blondel used a plan revised by another service within the King’s works. Portail’s ad hoc office had ceased activity in 1751 and the office of the First Architect, Ange-Jacques Gabriel, did not produce surveys of this type. As Guillaume Fonkenell recently demonstrated, Gabriel favored precise surveys of the masonry shell, such as the one conducted by Louis Le Dreux and Nicolas Marie Potain in 1749, and disregarded the labyrinthine interiors or the adjacent urban fabric. Fonkenell, “Relevés,” 35.

[28] Michèle Beaulieu, “Un groupe d’enfants de Jean-Joseph Vinache,” Revue du Louvre 31:5-6 (1982), 363; François Souchal, Les Slodtz, sculpteurs et décorateurs du Roi (1685-1764) (Paris: Éditions E. de Boccard, 1967), 90.

[29] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 4, 39.

[30] Jombert became libraire-imprimeur only in 1753, midway between the publication of volumes 3 and 4. Bousquet-Bressolier, “Jombert,” 312. Although all libraires-imprimeurs re-edited books (an important source of profit), Jombert specialized in the reissue of illustrated books. Success was more difficult to obtain in this domain since, unlike the classics of literature, ancient history, religion, or law—genres that always have a public—images and what they represent went out of fashion rapidly.

[31] Wallace Kirsop, “Les mécanismes éditoriaux,” in Henri-Jean Martin and Roger Chartier, eds., Histoire de l’édition française (Paris: Promodis, 1984), 2, 31-32.

[32] All prospectuses had to conform to a number of rules imposed by the corporation. For example, the typeface used in the prospectus and the spacing of the letters were to be the same as in the future book, as should be the paper itself. In short, the prospectus was a sample as well as a sales pitch. See Pierre-Joseph-François Luneau de Boisjermain, Mémoire pour les libraires associés (Paris: 1771), 25.

[33] It was the practice of editors to play with the ambiguity of what a “planche” designated. Was it the number of sheets of paper or that of the copper plates? By detailing the total number of sheets of paper used for the illustrations, the prospectus inflated the total number of images. Luneau de Boisjermain, Mémoire, 40-48. For the numbers presented here we assumed that one illustration equals one plate.

[34] It is possible that the price was even higher. According to Christian Michel, each volume of the Architecture Française was 75 livres when printed on Grand Raisin and 100 livres on Grand Nom de Jésus, although he does not provide references. Christian Michel, Charles-Nicolas Cochin et livre illustré au XVIIIe siècle (Geneva: Droz, 1987), 259.

[35] See Blondel, L’Architecture Française dite Le Très Grand Blondel, vol. I, n. p.

[36] “[N]ous profitons même de l’occasion de cette note, pour le prévenir, que quoiqu’on ait pu lui faire entendre, nous n’avons aucune part à l’interruption de l’Architecture Françoise.” Jacques-François Blondel, Cours d’Architecture, Ou Traité De la Décoration, Distribution & Construction Des Bâtiments, 9 vols. (Paris: Chez la Veuve Desaint, 1771-1777), vol. 3, 51-52, noted, cited in Aurélien Davrius, Jacques-François Blondel : un architecte dans la « république des arts » : Étude et édition de ses Discours (Geneva: Droz, 2016), 37.

[37] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 2, 153.

[38] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 2, 154 and vol. 3, 55.

[39] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 3, 80.

[40] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 2, pl. 222-224.

[41] Blondel, Architecture Française, vol. 1, 257.

[42] Gordon, “Recueils,” 143.

[43] Gordon, “Recueils,” 144-145. On Blondel’s plate of the Gobelins see: Katie Scott, The Rococo Interior: Decoration and Social Spaces in Early Eighteenth-Century Paris (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 59-60

[44] Mauban, L’Architecture Française de Jean Mariette, 78.

[45] Emil Kaufmann, “The Contribution of Jacques-François Blondel to Mariette’s Architecture Françoise,’’ The Art Bulletin 31:1 (March 1949), 58-59.

[46] “Hôtels particuliers à Paris.” École Nationale Supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris, 2015-2016.

[47] Blondel, L’Architecture Française dite Le Très Grand Blondel, vol. I, introduction.

[48] Davrius, Jacques-François Blondel: un architecte dans la « république des arts », 38.

Cite this article as: Pierre-Édouard Latouche and Jean-François Bédard, “A Plan of the Louvre’s Cour Carrée and the Making of the Architecture Française,” Journal18, Issue 2 Louvre Local (Fall 2016), https://www.journal18.org/934. DOI: 10.30610/2.2016.5

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.

Pingback: Smell of the Sea: A Review of the Musée National de la Marine – by Kelly Presutti – Journal18: a journal of eighteenth-century art and culture