Caroline Wigginton

These are the moccasins of Mohegan artisan Lucy Tantaquidgeon Tecomwas (1753-1834) (Fig. 1). Turning to their form, this essay reads with the moccasins’ design of multi-dimensional visual and material elements, especially their incorporation of the Trail of Life motif. In reading with form, it locates craft as a participant in the sustenance of Indigenous peoples and cultures. Mohegan authors and artists often discuss design as something that unites their community across space and time, whether that be design grounded in the craftwork of decorative household, sacred, and personal objects, or its porting to literary, performing, and visual arts.[1] Reading with Indigenous form reveals kinships created through aesthetics that endure across generations, objects, and artistic practices. Here, I analyze Tecomwas’s moccasins as well as a letter by her uncle Samson Occom to show how a distinct pattern like the Trail of Life, which embodies personal and communal pathways, can actively sustain kinship and promote peoplehood.

Formalist readings are an abiding method of both art history and my own field, literary studies, even as our practices have remained distinct. Seeking to align the wide variety of definitions of form across disciplines, Caroline Levine writes, “All the historical uses of the term, despite their richness and variety, do share a common definition: ‘form’ always indicates an arrangement of elements—an ordering, patterning, or shaping.”[2] Historically, settler colonial methodologies have recognized Indigenous forms while ignoring or simplifying their dynamic meanings, sophistication, and adaptability. This approach is motivated by the “logic of elimination” inherent to settler colonialism, which includes the subversion of cultural practices that help sustain a tribal nation’s peoplehood.[3] For Native communities, craftwork—the skilled making of items for domestic, sacred, curative, and collective purposes—remains a storehouse and workshop for the ongoing care for and practice of the patterns, both aesthetic and relational, that underpin Indigenous forms. Turning to craftwork to understand Indigenous aesthetics helps counter eliminatory logic and recovers genealogies of making that acknowledge, adapt, and extend expressions of peoplehood and personal creativity.

Conversations about the capaciousness and flexibility of craft aesthetics have been occurring in Native American and Indigenous Studies (NAIS), especially as they pertain to the arts of the twentieth century and beyond. For example, scholars have discussed how the principles that underpin basketry are important to understanding contemporary storytelling, writing, knowledge making, and so on.[4] In their introduction to The Shapes of Native Nonfiction, editors Elissa Washuta (Cowlitz Indian Tribe) and Theresa Warburton use basketry to explain and organize their anthology of contemporary lyric essays by Indigenous writers. They argue that understanding today’s Native literatures requires attending to the persistent material and formalist sensibilities pervading Indigenous expressive practices. These practices are grounded in craftwork and, by virtue of centuries of both colonialist and Native writings in and about Indigenous American places and peoples, inextricably entwined with scriptive modes as well. This essay follows their lead and those of like-minded scholars and knowledge keepers as it turns to eighteenth-century Mohegan creations.

The form of Tecomwas’s moccasins is rooted in Mohegan, a Native nation whose territories are claimed by present-day Connecticut. Now all but unknown outside of her tribal nation, Tecomwas was the daughter of Mohegan medicine woman Lucy Occom Tantaquidgeon (ca. 1731-1830) and niece of famed Mohegan leader and Brothertown Nation founder Samson Occom (1723-1792), whose letter is the subject of the final portion of this essay. Using tanned hide, beads, quills, and ribbon, the artisan stitched and adorned these moccasins in her teens, perhaps as early as 1767, prior to marriage and motherhood. To begin, Lucy Tantaquidgeon would have likely used her own feet as pattern for correctly sized pieces of hide. She may have pounded the cut edges to thin them and pre-marked holes before stitching them together using an awl and needle. The gathered seams stretch along the top of each foot, decorated with plaited quillwork in originally vibrant blue and red. Similarly colored and also undyed white quill-embroidery borders the plaiting. Where the plaiting creates a layered diamond arrangement, the embroidery allows for curvilinear, seemingly dotted, embellishment (Fig. 2). On the right shoe, twenty-two waves or curls flow alongside, cascading from ankle to toes. On the left, there are twenty-one. Using dark ribbon Tantaquidgeon has covered the stitching that attaches the moccasins’ ears (or flaps) to the shoe as well as the ears’ edges. She has encircled the ears with a vine of leaves and flowers, worked in white glass beads. These are special moccasins, ones to be worn—as evidenced by signs of use inside and on the toes—and also to be cherished and then given to a daughter to be passed on to other relatives. Later in life, Tecomwas gifted them to her daughter Cynthia Tecomwas Hoscutt (1778-1855). Hoscutt subsequently entrusted the moccasins to her own daughter, medicine woman Rachel Hoscutt Fielding (1800-1860), who in turn presented them to her son Moses Fielding (1833-1897). Moses Fielding was the last Mohegan bearer of these moccasins. He sold them to Abel Brooks in 1887, and they are now housed in the National Museum of the American Indian.[5]

In making these moccasins, the artisan stitched and layered together Mohegan design with her own eye, melding custom and innovation to craft their form. The colors and botanical components are common to Mohegan craftwork.[6] Of especial note for this brief essay, however, is their incorporation of the Trail of Life pattern, one of the principal design elements of Mohegan craftwork. As Melissa Jayne Fawcett explains in her biography of Gladys Tantaquidgeon (1899-2005), who was a medicine woman from 1916 to 2005, “The Mohegan Trail of Life is as old as memory. In each generation, elders pass on the knowledge of its ancient design to the Mohegan Indian people. . . The Trail of Life pattern decorates [personal craft] because life’s journey is itself a circle [and] because Mohegans record their life trails in their handiwork.” Specifically discussing Gladys Tantaquidgeon’s ceremonial regalia, Fawcett continues, “There are many ups and downs in the [regalia’s] trail design, reflecting the rolling hills of New England and the bumpy challenges of life itself. Dots beside the trail signify people met along life’s journey; leaves symbolize the healing medicine plants of the eastern woodlands.”[7]

In featuring the Trail of Life pattern, Tantaquidgeon’s regalia echoes the design of other craftwork all around her in Mohegan. Euro-American anthropologist Frank G. Speck, who met a young Gladys Tantaquidgeon while performing fieldwork in Mohegan in the 1910s and soon after became her mentor and teacher at the University of Pennsylvania, surveyed a variety of craftwork brought to him by Mohegan elders, including precious older objects. He notes the ubiquity of “alternating chain-like curves” on baskets and other art objects; the curves “are characterized . . . by intertwined lines, dots, and petals.”[8] It is present as well on objects dating to the long eighteenth century and on display at the Mohegan Nation’s century-old Tantaquidgeon Museum, including a magnificent story elm box.[9] Samson Occom made the box for his sister—Tecomwas’s mother—and their kin in Mohegan. He did so after he and other members of the community had departed westward to found the intertribal Native Christian nation of Brothertown in Oneida territories, in what is now upstate New York. Thus the Trail of Life both symbolizes the many aspects of a life’s journey and also remembers and enacts specific personal and communal journeys and pathways.

The pattern continues to persist in and across Mohegan aesthetics. For example, Mohegan playwright and performer Madeline Sayet introduces her solo Where We Belong (2022) by invoking the design element:

In Mohegan culture, we have a symbol, the Trail of Life, that depicts the ups and downs of life, and the people you meet along the way. This symbol is embedded in much of the design of WHERE WE BELONG because I embrace this trail as a journey, each night, as I learn different things about myself, my ancestors, and the world around me. . . . This journey continues and keeps evolving, as the world continues to move—like the river, the sky, the earth—holding stories that came before and those of this moment, which is ever changing.[10]

Here, Sayet’s explanation underscores not only the personal and communal longevity of the Trail of Life pattern but its dynamism.

What we see and touch in Tecomwas’s moccasins and other works of Mohegan art are the tangible aspects of an underlying form that “continues to move.” When these Mohegan women from multiple centuries turn to the same design element to depict their personal experiences, they “pas[s] on the practice of symbolic adornment” and “sustai[n] the obligation of bringing forward Mohegan traditions.”[11] The result is works of craft and other expressive arts whose forms include and then exceed a visual and textural pattern—lines, or trails, accompanied by dots and often linking other design elements—and summon the particularity of the maker’s life in kinship with Mohegan. The form follows, connects, and anticipates specific personal, familial, and communal journeys, including spiritual and natural ones. The Trail of Life pattern as form, its interconnecting and layered arrangement of curvilinear pathways of texture, color, sound, and narrative invokes the form of life in kinship itself.

Even as Tecomwas’ moccasins draw on this Trail of Life tradition, they also offer a meaningful variation. What distinguishes the Trails of Life present in most of these other women elders’ creations is the longevity of their personal experiences. Tecomwas’s moccasins, however, are the work of a young woman who is still learning her craft and at the beginning of her adulthood. (It is worth noting that rather than denigrating her craft as callow, Tecomwas and her family understood her moccasins to be treasured items.) Instead of the extensive singular or branching trails that undulate across other Mohegan objects, her Trail of Life pattern is composed of layers of quillworked embroidery, one on top of the other. Five rows border either side of the central plaited seam and over them are the dozens of waves in parallel, each composed of three curved lines. Each pathway supports and shelters the others, and the long ones at the base provide the foundation for the curling waves at the top, flowing and dancing in the same direction as the wearer’s steps. The moccasins celebrate the apprentice artisan. The cascade of waves on each of Tecomwas’s moccasins proclaim that she is a young maker who is building on the lives and lessons of her ancestors.

Or perhaps rather than waves these curls are instead or also spirals. Discussing the ubiquity of the spiral shape, literary scholar Lisa Brooks (Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi) notes, “This spiral is embedded in place(s) but revolves through layers of generations, renewing itself with each new birth. It cannot be fixed but is constantly moving in three-dimensional, multilayered space. It allows for recurrence and return but also for transformation.”[12] Like a fiddlehead’s coils or the growth lines of quahog shell, Tecomwas’s spirals signify emergent life within and across generational cycles. They honor the lives and craft of the artisans who have preceded and taught her and also announce her own joyful joining into a Mohegan kinship of making, each linked stitch another relative. The design of the moccasins suggests therefore that honoring the lives and experiences of others and repeating their knowledge is a generative act. And rather than proclaiming her static repetition, her design marks possibilities, a unique part of her own Trail of Life. The beadworked vines encircling the moccasins’ ears are yet another, other-than-human Trail of Life, sacred medicine that emphasizes the weightiness and beauty of that responsibility. The form of the moccasins creates and extends kinship across time and distance, linking Mohegan peoples through aesthetics sustained by craftwork.

Till now, this essay has focused on the form of Lucy Tantaquidgeon Tecomwas’s moccasins and its generative participation in aesthetic and communal kinship. For this final section, I turn to reading with form and follow Tecomwas’s moccasins as they guide us to a text written by her uncle Sansom Occom and its complementary form. In this way, the form of Tecomwas’s moccasins facilitates identifying kinships between craftwork and other expressive arts and, in turn, bridging disciplinary divides imposed by settler colonialism on Indigenous aesthetics.

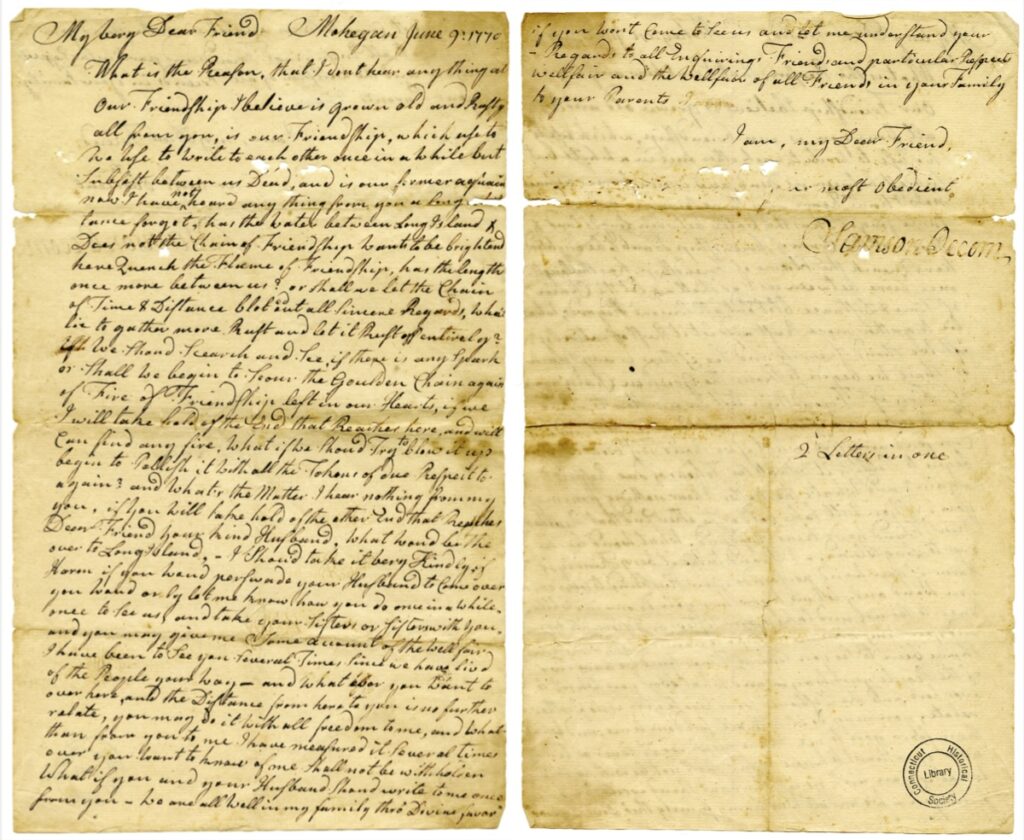

In June 1770 in Mohegan, around the same time Tecomwas stitched and adorned her moccasins, Occom wrote a letter to a “Very Dear Friend,” probably Esther Poquiantup, wife of his brother-in-law and other very dear friend Jacob Fowler, who was from Montauk, directly south across the Long Island Sound from Mohegan (Fig. 3). The letter is woven from two threads, as it interweaves alternating lines to lament the recent literal and emotional distance of their friendship. The first thread plaintively questions why the “Flame of Friendship” has dampened between them and with Occom’s customary wordplay proposes a rekindling through letters and a visit to Mohegan. The second thread employs a more formal tone and, rather than a flame, likens their friendship to a golden chain dulled and weakened by rust. Occom wants them to each take their ends and “pollish” it to “brighte[n]” and reforge their connection.

[Alternating lines have been italicized to signal visually the two threads of the letter.]

My Very Dear Friend

What is the Reason, that I dont hear anything at

Our Friendship I believe is grown old and Rusty

all from you, is our Friendship, which use to

We Use to Write to each other once in a While but

Subsist between us Dead, and is our former aquain 5

Now I have ^not^ heard any thing from you a long while

tance forgot, has the Water between Long Island

Does not the Chain of Friendship want to be brightend

have Quench the Flame of Friendship, has the length

once more between us? or Shall we let the Chain 10

of Time & Distance blot^ed^ out all Sincere Regards, What

lie to gather more Rust and let it Rust off entirely?

If We Shoud Search and See, if there is any Spark

or Shall we begin to Scour the Goulden Chain again

of Fire of Friendship left in our Hearts, if we 15

I will take hold of the End that Reaches here, and will

Can find any fire, What if we Shoud Try to blow it up

begin to Pollish it with all the Tokens of due Respect to

again? and What’s the Matter I hear nothing from my

you, if you will take hold of the other end that Reaches 20

Dear Friend your kind Husband, What woud be the

over to Long Island,—I shou’d take it very Kindly, if

Harm if you woud perswade your Husband to Come over

You Woud only let me know how you do once in a While,

Once to See us, and take your Sister or Sisters with you, 25

and you may give me Some account of the Well fair

I have been to See you Several Times Since we have livd

of the People your Way—and What ever you Want to

over here, and the Distance from here to you is no further

relate you may do it with all freedom to me, and what 30

than from you to me I have measured it Several times

ever you want to know of me Shall not be withholden

What if you and your Husband should write to me once

From you—We are all Well in my family thro’ Divine favor

If you won’t Come to see us and let me understand your 35

—Regards to all Enquiring Friends and particular Respects

Wellfair and the Wellfair of all Friends in your Family

to your Parent

I am, my Dear Friend, your most obedient

Samson Occom[13]

One cannot understand this letter without attending to form. As Angela Calcaterra argues, “The enjambment and alternating lines require the recipient to heighten her awareness, to engage with the letter’s form as much as its content, with its physical appearance on paper as much as its symbolic layering.”[14] Reading with Tecomwas’s moccasins locates this letter and its form in kinship with not only scriptive or paper texts by Occom and other authors, but also Mohegan aesthetics across modes of expression. Moreover, these aesthetics link to craftwork as a primary and enduring home of form. Like an embroidered or plaited quillwork trail, the alternating lines of Occom’s letter connect Mohegan to Montauk and Montauk to Mohegan to span and re-span the waters of the Long Island sound and replenish their friendship. The golden chain thread in particular aligns with the Trail of Life as line, while the flame thread emphasizes both life and fire’s capacities for ignition, decay, and resurgence. Occom has cleaved and then reunited the Trail of Life pattern. The enjambment—the breaking words and sentences across lines—further conjoins these threads, and Occom turns language into twined strands. Points where the two threads converge (e.g. “Friendship” in lines 2 and 3; “Use” in lines 3 and 4; “Well fair” in lines 26 and 37) echo the ebb and flow of distance in their friendship. And, at near center, Occom knots them together, just as he seeks to reknot the friendship, by inviting his friends to join with him in catching a “Spark” and “Pollish[ing]” the chain “again.” Reading with Tecomwas’s moccasins reveals that Occom’s letter too creates kinship with objects and peoples, as its design incorporates enduring elements of design and also traces a particular pathway between friends and communities.

Reading with Tecomwas’s moccasins reminds us that when it comes to Indigenous studies, art and literary histories cannot function, as they too often do, as isolated disciplines with distinct and separate interpretive practices and methodologies. Rather, they too are part of the same pathway. Moreover, reading with Tecomwas’s moccasins suggests that eighteenth-century makers were themselves consciously innovating with and through form rather than mechanically repeating traditional designs or passively assimilating settler colonial expectations. Tecomwas’s moccasins invoke a Mohegan form that is necessarily an adaptive one, a form that requires both reproduction and growth to be fully expressive, just like life itself. Reading with the moccasins therefore underscores that examples of expressive arts that deploy genres, techniques, or materials acquired under colonization remain Indigenous. Reading with Tecomwas’s moccasins stresses the role of women, including craftworkers, in sustaining Indigenous forms along with their aesthetics and creativity. Occom’s letter in turns underscores the interweaving of these functions of reading with form. As contemporary scholars, we can read with Indigenous authors and artisans and their crafted creations. Following in their path we can thereby witness and trace the primary forms of expression, discern innovation, respect kinships beyond settler colonial genres, and honor practice.

Caroline Wigginton is Chair and Professor of English at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, MS and the author of Indigenuity: Native Craftwork and the Art of American Literatures (2002)

[1] Scholars of the Native northeast also use form to describe social and communal structures. For example, in her discussion of multigenerational Mohegan leadership, anthropologist Marge Bruchac explains, “In 1831 [, . . .] three generations of Mohegan women—Lucy Occom Tantaquidgeon, her daughter Lucy Tantaquidgeon Teecomwas, and her granddaughter Cynthia Teecomwas Hoscott—deeded a half-acre plot on Mohegan Hill to settle [a Congregational church]. . . . The Mohegan church emerged from and complemented indigenous forms of traditional leadership and worship; it still expressly integrates both Native and Christian beliefs.” See Margaret M. Bruchac, “Hill Town Touchstone: Reconsidering William Apess and Colrain, Massachusetts,” Early American Studies 14, no. 4 (Fall 2016): 740, emphasis added.

[2] Caroline Levine, Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 3.

[3] Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 6, no. 4 (2006): 387. While Wolfe does not discuss aesthetics, craftwork, literature, or the arts per se, he does note that practice of settler colonialism includes “resocialization” and “biocultural assimilation” (388). Both resocialization and assimilation may involve the denigration, erasure, and replacement of customary practices.

[4] I have written more extensively on this topic elsewhere, discussing this scholarship, including the work of Washuta and Warburton, in relationship to American literary and book history and Native craftwork. See Caroline Wigginton, Indigenuity: Native Craftwork and Art of American Literatures (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022), 3–12.

[5] Fielding may have sold them for a variety of non-exclusive reasons. He may have needed money: under settler colonialism, many Indigenous artisans and their families have sustained themselves and their communities through trading and selling craftwork. He may have felt that Abel Brooks or someone connected to Brooks would be a better caretaker of the moccasins. Or he may have anticipated their ethnographical collection and wanted the moccasins and their form to teach other about Indigenous ingenuity.

[6] Gladys Tantaquidgeon, “Notes on Mohegan-Pequot Basketry Designs,” 1933, MS 44083. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut. See also Frank G. Speck, Decorative Art of Indian Tribes of Connecticut, Anthropological Series 10 (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1915).

[7] Melissa Jayne Fawcett, Medicine Trail: The Life and Lessons of Gladys Tantaquidgeon (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2000), 3.

[8] Speck, Decorative Art of Indian Tribes of Connecticut, 4–5. Many of the items pictured in his report are now at the NMAI, including two pairs of moccasins, cousins to Tecomwas’s.

[9] For discussion and images of the small box, which is about a foot in diameter, see “Samson Occom Box (c. 1785),” Mohegan Tribe website, https://www.mohegan.nsn.us/explore/museum/artifacts.

[10] Program for Madeline Sayet’s Where We Belong by Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, national tour. Playbill, 2022. In the published play, she writes instead, “This symbol is embedded in much of the design of Where We Belong, because what you are about to encounter is a journey along the trail, no more no less.” See Madeline Sayet, Where We Belong (London: Methuen, 2022).

[11] Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel, “Martha Uncas’s Belt,” Unfinished: America at 250 (blog), n.d., https://unfinished250.org/assets/martha-uncass-belt/.

[12] Lisa Brooks, “The Primacy of the Present, the Primacy of Place: Navigating the Spiral of History in the Digital World,” PMLA 127, no. 2 (2012): 309.

[13] Samson Occom, The Collected Writings of Samson Occom, Mohegan: Leadership and Literature in Eighteenth-Century Native America, ed. Joanna Brooks (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 92–93.

[14] Angela Calcaterra, Literary Indians: Aesthetics and Encounter in American Literature to 1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 49.

Cite this article as: Caroline Wigginton, “Reading with Indigenous Form: Lucy Tantaquidgeon Tecomwas’s Moccasins (ca. 1767),” Journal18, Issue 18 Craft (Fall 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7566.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.