Natalie E. Wright and Glenn Adamson

The video game Minecraft may be the most popular form of making that has ever existed. In any given month, there are 100 million users globally. In this virtual world, materials come out of the ground as pixelated graphics with the click of a button. (“Mine.”) Another click can turn these extracted resources into useful items. (“Craft.”) The making happens at a kind of digital workbench, represented in the user interface as a series of boxes that form a “crafting grid.” When a player has sufficient materials in their inventory, they drag the mined materials into the grid in specific patterns to form “recipes.” The items that players make can in turn become materials for other more complex objects, and so on. There are over 350 craft-able items on Minecraft currently, from candles to carpets, in materials ranging from diamond to terra cotta (in a variety of colored glazes). To make a barrel, for example, players begin by crafting wood planks from a wood block. Then, they combine the planks and—presto—a barrel appears in the “results” box, though strangely, like everything else in Minecraft, it is square in shape.

When making their barrels, players can choose between slabs of oak, spruce, birch, acacia, dark oak, mangrove, and bamboo, as well as “crimson,” “jungle,” and “warped” wood. In Minecraft, all that distinguishes these woods are their colors. In real life, of course, there are big differences between varieties. The processes are, accordingly, more complex: the wood must be cut into staves, bent using heat and moisture, and set into place within metal bands. Oak is a prudent choice for these actual coopering processes; bamboo would be ill-advised. This sort of knowledge of specific material properties can be called “material intelligence”—the inherent human capacity to understand and shape the physical world around us. This concept combines the person-oriented theories of tacit or embodied knowledge from anthropology with the material-oriented disciplines of science and technology, art and history. Material intelligence, at its fullest extent, incorporates insights from all these fields.

Material intelligence attends first and foremost to a given substance’s physical structure and properties, which in turn guide how it can be shaped and used. Ultimately, it takes into account the cultural meanings that have been projected onto substances. This approach expands upon anthropologist Tim Ingold’s discussion of the “two faces of materiality”: “on one side, the raw physicality of the world’s material character,” and on the other, “the socially and historically situated agency of human beings.”[1] Among other leading practitioners of the concept in art history is Jennifer L. Roberts, whose recent book, Contact: Art and the Pull of the Print, exemplifies a turn toward the studio as a site of art historical knowledge.[2]

Material Intelligence the magazine is a quarterly publication that promulgates the concept of its title. Each issue explores a single material. Begun in 2021 and published by the Chipstone Foundation, the issues to date have been on Oak, Linen, Rubber, Copper, Obsidian, Nylon, Leather, Terra Cotta, Paper, and Sand.[3] On the horizon are issues about Steel, Feathers, Wax, Charcoal, Acrylic, and Hair. The magazine is free for all to access. The issues begin with an editorial introduction, followed by a series of short essays on various topics by scholars, artists, and practitioners with a wide range of backgrounds and expertise. The tone is engaging and accessible, with articles at roughly 750 words apiece.

Material Intelligence comes at a time when this knowledge is both all around us and cultivated by very few. Reader, scan your surroundings. It is quite likely that your environment is populated by objects whose complexity of manufacture would have stunned earlier generations, and which you yourself may not understand well at all. At the same time, due to that very fact of complicatedness, which has been enabled by ever-increasing specialization, walled off by intellectual property regimes, material intelligence has fallen precipitously among the broader public. By tracing the intellectual history of material intelligence as a form of common knowledge, we see this loss beginning, arguably, in the twentieth century and accelerating dramatically in the twenty-first.

This splintering, as historian Jill Lepore has argued, can be traced through an unusual barometer: the declining popularity of encyclopedias.[4] They make for an intriguing contrast to the minimally distinguished materials of Minecraft; they show that highly explicit textual forms, as well as tacit hand processes, can embody material intelligence to a high degree. In her discussion of the Encyclopedia Britannica, for example, Lepore highlights the instructive example of sewing needles. Britannica’s entry elucidates the manufacturing steps involved in transforming the raw material of “Sheffield crucible steel” into an object with a fine point and an eye. It reads similarly to nineteenth-century “object lessons”—pedagogical tools designed to be physical manifestations of knowledge about materials and processes for the purpose of children’s education.[5]

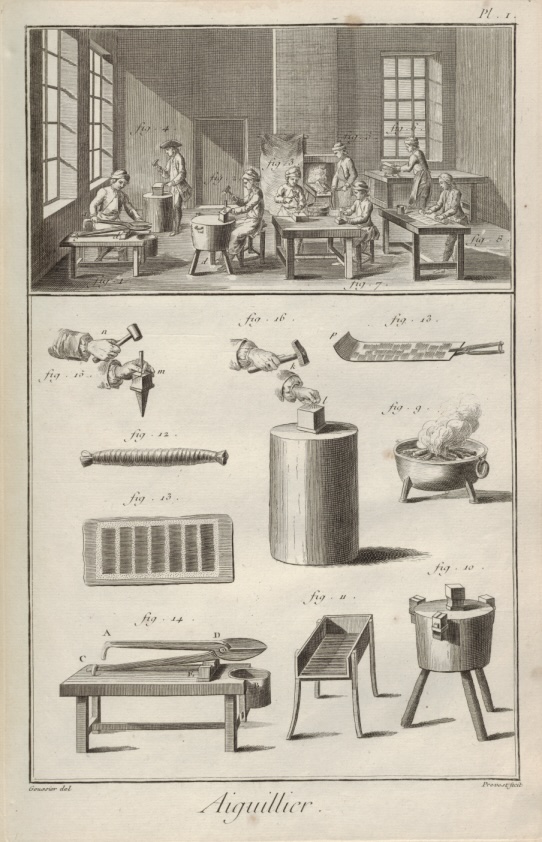

The Encyclopedia Britannica was a twentieth-century successor to antecedents that had also focused on material intelligence. One of the very earliest, Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, details in thirty-seven chapters everything from murex snails (a source of the Tyrian purple dye worn by emperors) to Roman gold mines in Spain. But it was in the eighteenth century that these comprehensive compendia really came into their own. Intuitively ordered manuscripts gave way to more self-consciously rigorous and comprehensive undertakings, most famously Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, which also introduced the term itself (earlier publications were titled “dictionaries”).[6] The trade plates in the Encyclopédie (Fig. 1) illustrate processes and tools for “all the necessary things of life.” It also uniquely brought together the mechanical and liberal arts.

Our own publication, Material Intelligence, is something like an encyclopedia in that each issue acts as an expansive entry for a single material with a definition (the introduction) and examples (the articles). Obviously there are many differences between our approach and Diderot’s, but there are some points of continuity as well. Consider his article on the stocking machine. As literary scholar Joanna Stalnaker has shown, Diderot struggled with its immense complexity.[7] He had to gather information about the machine from multiple sources, including images, texts, discussions with artisans, and firsthand experiences. This firsthand experience involved Diderot disassembling and reassembling the machine in miniature, which he described in detail for readers so that they may imagine its different parts and how they functioned together. However, this never coalesced into a coherent picture for the reader, a fact that Diderot himself conceded, noting mid-article that the stocking machine might simply be too complicated for the reader to understand. In that moment, his goal changed from teaching the reader about the stocking machine’s inner workings, to heightening their appreciation for the artisan’s knowledge and the machine’s complexity.

Our material world is filled with metaphorical stocking machines: the sheer complexity of contemporary manufacturing may seem to render the accessible tone and slight length of Material Intelligence absurdly inadequate. However, we have never pretended to comprehensiveness, which necessarily requires specialist language. Our episodic approach is meant to be suggestive, hopefully opening up avenues of inquiry through surprising juxtaposition. Like Diderot, who consulted a variety of sources to understand the stocking machine, we invite contributors from many different disciplinary contexts, and press disparate sources into service. To make this work, the material for each issue has to be broad yet specific enough to hold such divergent histories and perspectives. The sequencing of materials in a given year, too, differ from one another across categories such as animal, vegetable, mineral, and synthetic. Material Intelligence’s designer, Wynne Patterson, brings these divergent topics together through illustrated drawings that create the overall identity of the publication.

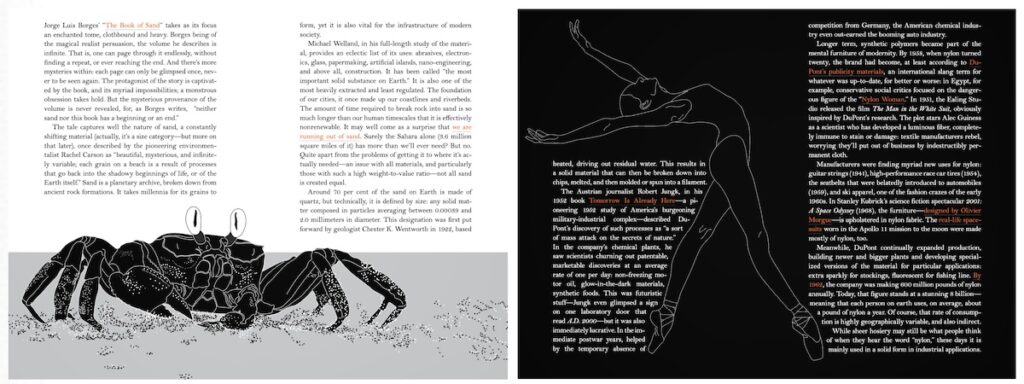

The visuals of the magazine further this implication of a larger story. “Marginalia” that punctuate the articles allude to objects, technologies, and histories not covered by our authors. Taking inspiration from the artist Fred Wilson, a true poet of surprising contrasts, we often pair marginalia images and quotes that invert expectations and highlight power dynamics. In the Sand issue, for example, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1886 painting Bonaparte Devant le Sphinx (Bonaparte Before the Sphinx) is accompanied by a 1969 Temptations song lyric: “I can build you a castle from a single gain of sand.” The result is a complicated implied narration of the image, which shifts the role of speaker from Napoleon Bonaparte—and his violent colonial ambitions—to the Sphinx. While much scholarship has addressed the tension between language and visualization in encyclopedias, in particular the limitation of both forms to convey information about materials and the makers who fashion them, we see their relationship as a form of play rather than disconnect (Fig. 2).[8]

Our approach also indicates the methodological breadth that material intelligence encourages, as a driving concept. Themes we have explored in our first two years of publication include indigenous and disability epistemologies, literary metaphor, postcolonial critique, and generally, a lively suspicion of progress as the leitmotif of material histories. Crossing over such radical differences in perspective puts matter at center stage, while pointing to connections across profound gulfs of geography, culture, and time. Following where materials lead us, we have been able to move beyond the confines of the Anglo-European tradition in material culture studies and decorative art history, building on important work by scholars such as Edward S. Cooke, Jr.[9] We follow what Sarah Anne Carter and Ivan Gaskell describe as “material pluralism,” a methodology which ideally “imbues the history of a variety of world cultures with equal weight.”[10]

We have already addressed our similarity to historical encyclopedias; this pluralism is a way to address their limitations. As Jacques Proust has argued about Diderot’s Encyclopédie, the plates omit the “misery and exploitation, the fatigue, the pain, the violence, the fear, the herds of men, women, and children crowded into uncomfortable, dark, smoky workshops and factories.”[11] They offered fictional idealizations of artisanal labor. Modern encyclopedias such as the Britannica had major problems, too. Despite being marketed as “The Sum of Human Knowledge,” the Britannica was written from a manifestly Eurocentric perspective. It was also cost prohibitive—a business model doomed to fail. By the 1960s, sales of encyclopedias plummeted; in 2012, the Encyclopedia Britannica went fully online (Fig. 3). Wikipedia set out to change that by being free and editable—an extraordinary reversal of the centralized enlightenment model—but in doing so it also lost its claim to authority. It is something to be read, but rarely cited. As a free, digital, scholarly-leaning publication, Material Intelligence attempts to thread a needle amidst the contemporary crisis of institutions and expertise, while also prioritizing marginalized histories and the central role that materials have played in their continual unfolding.

Within the parameters of the long eighteenth century, for example, our approach has made possible inquiry about how ships made of oak and copper sheathing were crucial to the brutal operations of the Atlantic slave trade; the ways in which England’s manipulation of Irish linen production caused the Great Famine; the use of linen in so-called “negro cloth” that enslaved persons were forced to wear in the southern United States; the indigenous origins of so-called “Russia leather” from present-day Siberia; the medicinal and gastronomical cultures around bùcaros de Indias (low-fired burnished earthenware ceramics from the “Indies” or Americas). Our recent Steel Symposium in collaboration with the University of Birmingham’s Centre for Material Culture and Materialities also gave a window into the forthcoming issue, including how authors will engage with eighteenth-century topics.[12] Historian Jenny Bulstrode presented on African gong languages and metallurgy practices in the Black diaspora, while curator Rose Camara discussed the complexities of language around Indian ekku, also known as “Wootz” steel.

Minecraft presents a vastly different case study than the material intelligence in the eighteenth century that encyclopédistes sought to capture and disseminate. It is an instance in which a desire for making is combined with material anonymity—a contradiction that itself mirrors the comparative surplus and dearth of material intelligence today. Could a contemporary repository for our collective material intelligence make a difference in elevating this capacity to common knowledge? If human knowledge were somehow pooled together, all put in one place, then we could see clearly what we humans know about matter, more than we ever have before. Sadly, such a collection does not exist. Indeed, it is hard to see how, given the reality of proprietary interests, it could possibly come about. We do hope, however, to have made a small contribution to such a syncretic view, and if nothing else, to demonstrate the enduring importance, in a digital age, of material intelligence—this innate human faculty that is so easily fragmented, but will always connect us all.

Natalie E. Wright is a PhD candidate in Design History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she is also Contributing Editor of Material Intelligence magazine

Glenn Adamson is a curator, writer and historian based in New York and London, and Editor of Material Intelligence magazine

[1] Tim Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture (London: Routledge, 2013), 27.

[2] Jennifer L. Roberts, Contact: Art and the Pull of the Print (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024). This book comes out of Roberts’ A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, National Gallery of Art, 2021, https://www.nga.gov/research/casva/meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/roberts-2021.html.

[3] Readers can find these issues at https://www.materialintelligencemag.org/. The Chipstone Foundation has been at the forefront of curatorial practice and pedagogy with its changing galleries at the Milwaukee Art Museum, yearly “Object Lab” programs for undergraduate students, and “Think Tank” events for museums across the country. Material Intelligence joins the Chipstone Foundation’s two other journal publications, Ceramics in America, and American Furniture (the journals of record in their fields).

[4] Jill Lepore, “Information, Please!” The Last Archive, podcast audio, October 27, 2022, https://www.thelastarchive.com/season-3/episode-one-information-please.

[5] Sarah Anne Carter, Object Lessons: How Nineteenth-Century Americans Learned to Make Sense of the Material World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[6] Historian of science Pamela Smith and her team have explored these earlier manuscripts through the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University, https://www.makingandknowing.org/.

[7] Joanna Stalnaker, “From Stocking Machine to Word Machine,” in The Unfinished Enlightenment: Description in the Age of the Encyclopedia (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), 109–123.

[8] See, in particular, John Bender and Michael Marrinan, “Descriptions,” in The Culture of Diagram (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), 53–91.

[9] Edward S. Cooke, Jr., Global Objects: Toward a Connected Art History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022).

[10] Sarah Anne Carter and Ivan Gaskell, “Introduction: Why History and Material Culture?” in The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 7.

[11] Quoted in Stalnaker, The Unfinished Enlightenment, 114; Jacques Proust, Marges d’une utopie: Poure une lecture critiques des planche de l’“Encyclopédie” (Congac, Fr.: Le temps qu’il fait, 1985), n.p.

[12] This symposium took place on Friday, April 26, 2024, https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/historycultures/departments/history/events/2024/material-intelligence-workshop-%e2%80%93-steel; our first symposium was in collaboration with the Center for Design and Material Culture at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with the theme “Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Material Intelligence in Context,” https://cdmc.wisc.edu/event/material-intelligence-workshop-i-animal-vegetable-mineral-material-intelligence-in-context/.

Cite this article as: Natalie E. Wright and Glenn Adamson, “Encyclopædia Materia: Material Intelligence and Common Knowledge,” Journal18, Issue 18 Craft (Fall 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7480.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.