Yve Chavez

In the 1930s, artist Edith Hamlin painted a mural for San Francisco’s Mission High School titled Civilization Through the Arts and Crafts as Taught to the Neophyte Indians, in which she depicted Native women preparing wool yarn and weaving wool cloth on a standing loom (Fig. 1). In the background of the central part of the mural, a young Native woman holds a basket bowl out toward the Franciscan missionary. When this mural was first brought to my attention, I was puzzled as to why Hamlin depicted the Native women weaving on a loom. To a scholar of California Indian art, this weaving activity seemed out of place and not representative of the Indigenous ancestral practices that continued at the missions in the eighteenth century. Through further investigation, I realized my oversight: loom weaving did occur in the California missions because colonists introduced the practice to assimilate Native people.

In keeping with the theme of this special issue, the mural’s side-by-side depiction of loom weaving and basketry presents an opportunity to critically examine the roles occupied by basket weaving and loom weaving within a mission context.[1] For this study, I focus on art within an Indigenous context and craft as a Western concept. I build on the work of John Paul Rangel who describes Native art as “works that build on Indigenous cultures, traditions, and creative expressions while also innovating and developing new traditions.”[2] California Indian basket weavers built on ancestral traditions, and they were innovative in developing new shapes and designs for the baskets that they wove at the missions. I use craft to distinguish European practices, in this case, loom weaving, from Native arts because craft represents a hierarchical and Western view of material culture. Elissa Auther links the hierarchy of art and craft to the Renaissance “when the first claims were made for painting and sculpture as ‘liberal’ rather than ‘mechanical’ arts.”[3] Auther also situates “craft’s subordination and marginality as indispensable to the evolution of art.”[4] With Auther’s points in mind, I position craft as a “mechanical” practice that served a utilitarian purpose with the potential to be developed into art.

Though both loom and basket weaving were, by the twentieth century, lumped into the category of arts and crafts, such categorization was based on a non-Native, rather than Indigenous, view of the practices. As Molly Lee has explained, Native American and Alaska Native baskets appealed to an early twentieth-century Arts and Crafts Movement interest in “communally based handicrafts.”[5] Baskets fell into the craft category because of what they represented to collectors: the past. Elizabeth Hutchinson identifies the separation of Native American art and craft as a twentieth-century phenomenon in which “handicrafts” were associated with “traditional” arts as opposed to “modern Native American art.”[6] Early twentieth-century collectors’ interest in baskets as “antimodern” overlooked basket weaving’s continuity and adaptability to outside influences.[7] However, basket weaving existed before, during, and after the mission era. The early twentieth century saw the categorization of basketry as craft, but looking back at the eighteenth century it becomes apparent that both Native and non-Native people viewed basketry as surpassing craft.[8] Loom weaving, on the other hand, was confined to the mission era, which was part of the long eighteenth century. California Indian basket weavers were highly skilled individuals who made things that were both utilitarian and visually stunning reflections of the makers’ innovation and artistry. In contrast, there is no documented evidence that California Indians living at the missions embraced loom weaving as a medium for creating complex designs as they did in basketry.

Historical records and documents do not specifically place basketry or loom weaving into distinct categories of craft or art, but these practices occupied significantly different places in California Indian cultures. To dignify the weavers and to distinguish basket making as a practice with greater cultural value than loom weaving, this article resituates California Indian basketry as a form of art that is innovative and rooted in Indigenous knowledge. Loom weaving served a colonial goal of assimilating Indigenous people to settler ways. Loom weaving also produced objects that served a practical purpose: to clothe Indigenous people in garments deemed acceptable by European standards. No known examples of mission era textiles have been preserved, and only Mission La Purísima has displays of loom weaving equipment and tools (Figs. 2–3).[9] Loom weaving never took hold, or was abandoned, because it was never adopted as a viable mode of expression or vehicle of tradition for Native artists. A comparison of what is known about basket and loom weaving is useful to consider when addressing the position loom weaving occupied in colonial California, namely, its origins as a settler-imposed practice. This comparison illuminates the forgotten practice of loom weaving and offers a corrective to the status of basketry.

To fill in the gaps about the history of loom weaving and to highlight the continuity of basket weaving, this article begins with an overview of California mission history and Indigenous material culture. Then, it discusses basket weaving as an art practice before tracing the introduction of loom weaving to California. Because the California missions were active beyond the eighteenth century, I examine late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century descriptions of mission-based loom weaving and its byproducts. A discussion of imported cloth clarifies the factors that contributed to loom weaving’s failure to take hold and its eventual decline in California. Both practices were linked to modes of adorning or covering the body, one as part of traditional dress, the other as a way to rudely cover and assimilate the body. Basket weaving was a practice that preserved and extended community and individuality, whereas loom weaving was designed to efface this potential.

California Under Colonization

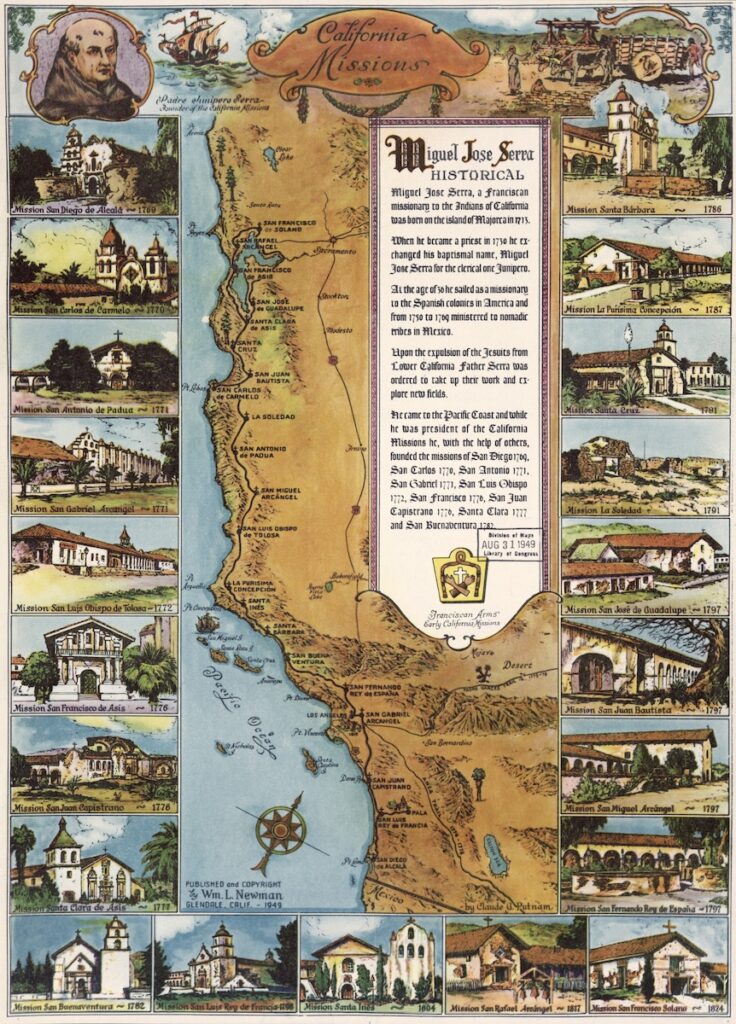

Missionaries of the Jesuit order established the Baja California missions prior to their expulsion from Spain’s territories in 1767. In 1768, a group of fifteen Franciscan friars under the leadership of Father Junípero Serra arrived in Loreto, Baja California to oversee sixteen missions. The Franciscans founded one mission in Baja California before they moved north, with the assistance of soldiers and lay people, to build missions in Alta California (hereafter referred to as California) for the Bourbon monarch. In 1769, the Franciscans arrived in San Diego, California where they created the first and southernmost Mission of San Diego de Alcalá. The Franciscans instituted seventeen missions during the eighteenth century and four in the early nineteenth century (Fig. 4). In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain and the new nation assumed power over California. The Franciscans established the last and northernmost mission in Sonoma in 1823. In 1834, California Governor José Figueroa put into action the plan for secularizing the missions, turning the churches into parishes administered by lay priests instead of mendicant friars.[10]

At the time of the missionaries’ 1769 arrival, the California Indian population is estimated to have numbered about 310,000.[11] The Serrano, Cahuilla, Kumeyaay, Cupeño, Payómkawichum, Acjachemen, Gabrieleño, Tataviam, Chumash, Yokuts, Salinan, Esselen, Ohlone, Coast Miwok, Pomo, and Wappo, among other communities, felt the effects of the twenty-one Franciscan missions.[12] These communities spoke unique languages and practiced their own customs. At the same time, shared practices existed across Indigenous communities, such as making garments and weaving baskets (the materials of which varied depending on regional resources).

Weaving and Garments in California Before Colonization

Prior to the Spanish incursion, California Indians relied on plant sources for cordage, and on animal pelts from rabbit, deer, fox, squirrel, wildcat, and coyote for clothing and blankets.[13] The Gabrieleño people, named for Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, inhabited the present-day Los Angeles Basin, parts of northern Orange County, and the four southern Channel Islands (Santa Catalina, San Clemente, San Nicolas, and Santa Barbara) off the west coast of southern California. They made blankets from “strips of rabbit fur woven together with milkweed or yucca fiber,” according to Lowell John Bean and Charles R. Smith.[14] Islanders used otter skins, which would later appeal to nineteenth-century Russian fur traders.[15] In some California communities, men either did not wear clothing or simply wore deerskin wrapped around the waist, while women typically wore a skirt or apron of buckskin.[16] Special occasion garments would be worn for ceremonies, including dances. Male dancers wore headdresses with feathers from local native birds, loin cloths made from animal skins, and body paint derived from mineral sources. Women in some communities wore basket caps, multiple strands of beaded necklaces, and skirts. Special occasion basket caps were adorned with geometric patterns.[17]

Our knowledge of these garments does not come from California Indians, who left no known written accounts prior to the Franciscans’ arrival. The historical record only retains European men’s written descriptions of California Indian culture, which reflect the authors’ biases and interests. European explorers who visited California after the Spanish incursion remarked on the fine workmanship that went into making special occasion regalia. Fray Juan Vizcaíno observed in 1769 that the Chumash used flicker, raven, and woodpecker feathers in their dance attire.[18] Members of the Vancouver Expedition that reached the Santa Barbara region of California in 1792 wrote about the garments and accoutrements Chumash people wore for celebrations and ceremonies. One member of the expedition, George Goodman Hewett, acquired Chumash-made objects like feather-adorned hairpins, which were reserved for dances and not worn every day.[19] Expedition surgeon Archibald Menzies wrote that the women “sometimes wear on their heads little Osier baskets which fit close & are finely wove & they generaly [sic] have beads of other ornaments appending from their ears.”[20] Vizcaíno’s and Menzies’s descriptions indicate when they saw the Chumash people wear adornments, but the men provide no explanation for the significance of the objects, evidencing their lack of cultural awareness or understanding. Regalia, like baskets, embody the technical, material, and cultural knowledge of their Native makers, which they passed down across generations.

Basket Weaving as Art

California Indians are best known for their basketry, which caught the attention of European colonists and explorers beginning in the eighteenth century (Figs. 5–6). Even prior to outside interest in baskets, these were highly valued belongings that Native peoples gifted to relatives, burned in funerals, used to store personal treasures, and to prepare and cook food. In their baskets, weavers incorporated complex designs that represented their knowledge of plants and natural dyes.

Before a weaver started to make a basket, they had to cultivate native plants that grew within their homelands. For southern California tribes, common basket plants include juncus, sumac, deergrass, sedge, and redbud. Along the central coast between the San Francisco Bay and Monterey County, weavers used sedge root, deergrass, bulrush root, and bracken fern. Some groups like the Salinan also incorporated feathers into their fancy baskets and later used European trade beads in place of shell beads.[21] The Coast Miwok on the northern edge of the missions’ extent used sedge root and bulrush root in their coiled baskets, which they sometimes decorated with feathers and Olivella shell disc beads.[22] At specific times of the year, weavers would gather basket plants from specific spots to avoid competition and over picking. After collecting their materials, weavers would dry the stalks and sometimes dye them using natural pigments.

The coastal communities of the Pomo down to the Kumeyaay in the far south are best known for their coiled baskets. Coiled baskets consist of wefts wrapped around a foundation that spirals about a center knot, as seen in figures 5 and 6. Weavers interlaced plants of different colors among a coiled basket’s wefts to create a variety of designs that stood out from the primary plant material being used. Patterns or designs appeared as horizontal bands that formed a single layer around a basket’s circumference and varied across California’s Native communities. The Chumash, for instance, are known for incorporating a primary band just inside the outer rim of their coiled baskets, as seen in figure 6, followed by sections of alternating wefts of dark and light colors called rim ticks.[23] Other design elements included diamonds, triangles, steps, lightning designs, botanical-inspired shapes, x shapes, and checkerboarding.

Weavers continued to experiment with new patterns and basket shapes after missionization in 1769. Basket weaving endured at Mission San Luis Obispo and Mission Santa Clara and is best documented at Mission San Buenaventura. Archaeological investigation has revealed impressions of baskets within the flooring of housing complexes Native people occupied at some of the missions.[24] Impressions of baskets can tell us that people were still weaving, or that they were still using baskets they had brought with them to the mission.

Mission San Buenaventura stands out because it is the only California mission where weavers’ names were recorded. In an unprecedented move, three weavers named Juana Basilia Sitmelelene, Maria Marta Zaputimeu, and Maria Sebastiana Suatimehue wove their names in the baskets they made at the mission. The presence of signatures in baskets is exceptional considering that the Chumash did not have a written language and no known established practice of artists signing their work. These three weavers also reinterpreted designs found on Spanish pesos into the concave surface of their coiled baskets, as seen in figure 5. These designs included the Bourbon monarch’s coat of arms, the pillars of Hercules, and interlocking globes, which when viewed on a basket signify the extensive reach and visual influence of Spain’s global empire. Seven examples of these baskets are known to have survived and can be found across international museums and private collections.[25]

Basket weaving continued at Mission San Buenaventura in part because the Franciscan friar in charge there saw the value of baskets. In 1812, Fray José Señán sent baskets to the College of San Fernando in Mexico City to pay for church furnishings.[26] One of the weavers, Sitmelelene, even wove a basket with border text that specified, in Spanish, that it was made at the request of the governor.[27] Basket weaving continued to garner the attention of non-Native collectors and patrons after the missions were secularized in 1834. Despite this, basket weaving declined over the middle part of the century, due to mission expectations that Native people assimilate and abandon their Native culture. Only when the Arts and Crafts Movement, from the 1890s to the 1930s, emphasized and encouraged the purchase of handmade decorative objects did the market for baskets surge again.[28] During this period, sometimes called the “Basket Renaissance,” descendants of mission survivors and weavers from other communities made baskets that non-Native collectors purchased. Ultimately, weaving went dormant for some communities like the Chumash and Gabrieleño because elder weavers passed away and younger generations immersed in settler society took little interest in maintaining the practice.[29]

Basket weaving was an avenue through which California Indians could retain connections to their homelands that settler colonists had exploited. Basket weaving celebrated ancestral knowledge and values such as respect for the natural environment and community. It was a honed skillset passed down through family generations that produced baskets with complex designs that channeled a weaver’s unique style. In contrast, loom weaving was a foreign practice that coincided with the exploitation of California’s landscape, including the razing of native plants by foreign sheep and the clearing of vegetation for cotton plants. California Indians who learned loom weaving received cursory training from foreign experts, sometimes even from Franciscans who themselves had little knowledge of the practice. Loom weaving yielded dull fabrics colored only by the white or black wool of mission sheep, or by cotton.[30] It was a practice intended to assimilate Native people to lifestyles deemed acceptable by European standards.

Loom Weaving in Colonial California

The clearest documented instance of Spanish colonizers introducing loom weaving to Native peoples at the California missions occurred twenty years after the Franciscans established the first mission in 1769.[31] Loom weaving—a relatively short-lived practice—was intended to replace the missions’ dependency on imported fabrics. Much of the cloth imported in the early years of the missions also required the importation of sewing materials to transform it into clothing.[32] Writing in 1775, Fray Junípero Serra wrote that Monterey had received “Three bolts of striped coarse woolen cloth. One bolt of baize or thick flannel and a half-bolt of Querétaro cloth, for the Indians from California who will act as servants. A hundred sheepherders’ blankets for all.”[33] Earlier that year, Serra had expressed his concern in a letter to Fray Francisco Pangua that the missionaries located in Monterey would not have enough clothing for the Native people there.[34]

To Serra, clothing was an essential aspect of being Christian.[35] Albert P. Lacson emphasized this point, arguing that the Franciscans saw clothed Indigenous bodies as “symbols of their evangelization success (or failure).”[36] Loom weaving further reinforced the Franciscans’ desire to successfully convert California Indians. Rather than relying on the imported cloth and garments the Franciscans provided within the first two decades of their California stay, Native peoples who learned to weave gained practical skills that might keep them busy. Ideally, they would continue loom weaving after the Franciscans completed their task of evangelization, which came to an end with the missions’ secularization beginning in 1834.

The historical record mentions the names of two men that the missions hired to travel from central New Spain to teach California Indians how to weave cloth on a loom. In 1792, Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén wrote to Governor Arrillaga that Antonio Domingo Henríquez had traveled from Mission San Diego to Mission San Carlos along with his wife. Lasuén explained that Henríquez “has taught carding, spinning, and also the weaving of various woolen cloths, also of the Sayal Franciscano (coarse woolen cloth) of which they have already made clothing for some missionaries.”[37] Henríquez had previously introduced loom weaving to the missions between San Diego and San Luis Obispo. He “made spinning-wheels, warping-frames, combs, looms, and all the utensils of the art save carding instruments.”[38] In 1796, another weaver with the last name Mendoza (originally from what is now Mexico) was sent from Monterey to Mission San Juan Capistrano to teach the Native people there. In the 1880s, historian Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote, “A loom was set up with other necessary apparatus of a rude nature, with which by the aid of natives coarse fabrics and blankets were woven. Early in 1797 the friars were notified that if they wished the services of Mendoza for a longer time they must pay his wages; but they thought his instructions not worth the money, especially now that they had learned all he knew, and the weaving industry had been successfully established. Besides home manufactures San Juan supplied from its large flocks quantities of wool for experiments at other establishments.”[39] Primary source accounts support Bancroft’s indication that the expectation was for California Indians to work independently after they learned basic weaving skills.

Tasks at the missions were typically gendered, including loom weaving, which Native women learned.[40] During the Vancouver Expedition’s visit to California between 1792 and 1794, Captain George Vancouver observed that unmarried women and girls prepared, spun, and wove the wool.[41] By 1806, Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff also observed women “cleaning and combing wool, spinning, weaving, etc.” Loom weaving functioned as a woman’s practice at the missions, thereby representing gender roles imposed at the missions. There is documented evidence of Native men sculpting stone statuary for the missions, which was an artistic skill men also learned in art academies like the Royal Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City.[42] Loom weaving was not part of academic training, but a craft that required the practitioners to also make the tools and looms upon which their work depended.

Not all the missions hosted highly skilled weavers like Henríquez and Mendoza, with many relying instead upon the resident missionaries to teach Native people how to weave on the loom. Vancouver observed at Mission San Francisco de Asís that a large room was dedicated to the weaving of wool. He explained that the Native people made the looms under the missionaries’ direction and described these looms as “rudely wrought” but “tolerably well contrived.”[43] The women who spun and wove the wool did so to produce clothing for the Native people. Langsdorff reaffirmed Vancouver’s observation that the missionaries taught the women at Mission San Francisco de Asís. He noted that the wool at that mission was “very fine and of superior quality” but that the “tools and looms are of a crude make. As the misioneros are the sole instructors of these people, who themselves know very little about such matters, scarcely even understanding the fulling, the cloth is far from the perfection that might be achieved.”[44] Langsdorff and Vancouver’s accounts are certainly not objective in their assessment of the materials and tools, and it is unclear by what standards they were judging Native weaving at the missions. Aside from their critical assessment of the looms, both men confirmed that the Franciscans taught loom weaving despite having little knowledge of the practice.

Missionaries’ accounts reveal that California Indians did not embrace loom weaving. Between 1813 and 1815, the missionaries of eighteen of the California missions responded to a set of questionnaires about the status of Indigenous customs. One of the questions asked about the clothing Native people wore. The missionaries’ responses varied according to the resources available at a given mission. For Missions San Luis Rey, San Fernando, Santa Inés, San Carlos, San Juan Bautista, Santa Clara and San Francisco, the missionaries all wrote that the Native people wore wool garments they made on site.[45] At Missions Santa Barbara and San Antonio, Native people made garments out of cloth the missionaries gave them.[46] According to the Franciscans at San Luis Obispo, Native weavers made garments without any instruction and the result was clothing that was “poor” in appearance.[47]

The Franciscans commented in the 1813–15 questionnaire that Christianized Native peoples typically no longer wore ancestral style garments and that only the “pagan” Indians living outside the mission did. At Mission San Luis Rey, the missionaries wrote that “the clothing of the pagans, generally, is their natural nakedness. When the weather is cold, however, they wear a kind of cloak made of rabbit skins. The women, besides wearing this rabbit skin cloak, always wear a kind of fringed apron to cover the parts of their body required by decency.”[48] The friars at Missions San Gabriel and San Buenaventura also commented on the Native preference to go unclothed.[49] Fray Antonio Rodríguez at Mission San Luis Obispo made a point of emphasizing that “in their pagan state” the Native people dressed like Adam (as in the Garden of Eden).[50]

Wool was not a material to which California Indians were accustomed. Native, undomesticated mountain sheep inhabited California before colonization and continued to roam the mountains in the second half of the nineteenth century as naturalist John Muir observed in 1874.[51] Despite their presence in California, native sheep were not utilized as sources of wool by California Indians either before or after colonization. Instead, imported sheep provided wool at the missions. Mission San Francisco used merino wool and Mission San Diego relied up imported Churro sheep.[52]

California Indians did not embrace wool cloth because it was not part of their established material culture; and furthermore, more appealing options became available through the missions. In response to the 1813–15 questionnaire, Mission San Antonio replied that “Many today are not satisfied with the clothing the mission gives them and are anxious to obtain clothes similar to those worn by the whites.”[53] Likewise, at Mission Santa Barbara, the clothing of the gente de razón was preferred and was provided as reward. In response to the questionnaire, the missionaries there stated, “to those who show more effort in some labor or service, we give clothes such as the gente de razón use.”[54] Fray Mariano Payeras at Mission La Purísima also observed that the newly baptized Native people were willing to do work in exchange for clothing that came from Mexico. Payeras describes that clothing as “skirts for the women, cloth, silk handkerchiefs, blue cloth for jackets and trousers, shirts and cotton underwear, etc.”[55]

In addition to wool cloth, Henríquez taught Native people to weave “cotton shirting” and sheets.[56] E. Philpott Mumford states that Henríquez’s 1792 arrival coincided with the earliest record of cotton manufacturing in California.[57] Some of the cotton weavers used was grown at the missions, but the plant was not well suited to the climate. Attempts were made to grow cotton at Mission San Gabriel in 1808, but the crops failed due to the colder temperatures.[58] Cotton evidently grew better in the warmer climates of Mexico, including Baja California. Fray Francisco Palóu wrote of Mission San José Comundú in northern Baja California Sur that “They raise considerable cotton, with which they make cloth to help out with the clothing; and they make blankets from the wool of the sheep.”[59] Cotton cloth production continued at Mission San Diego after the missions were secularized in 1834, but it appears to have ceased at the missions to the north. Between 1841 and 1842, French explorer Eugène Duflot de Mofras observed at Mission San Diego that “what cotton is produced is of a superior quality.”[60] Webb claimed, however, that “most of the raw material was brought up by supply vessels from San Blas.”[61]

Loom Weaving After the Missions

Loom weaving never reached an industrial scale in the California missions, nor did its products ever replace imported fabrics.[62] Despite this ultimate failure, its introduction in the late eighteenth century reveals the long history of colonial assimilationist techniques. In the later years of the mission era, California came to rely on imported cloth. In her study of Mission San Diego, Susan Hector points out that imports replaced the need for locally made yarn as early as 1821 when Mexico won independence and “had opened up trade with the United States.”[63] The missions’ 1834 secularization and eventual closure meant there was no longer an infrastructure to support the weaving of wool cloth from mission-raised sheep or cotton. Native people who had lived at the missions found work on ranchos, cultivating crops or herding livestock among other physically demanding tasks. Women sometimes worked as seamstresses and combed wool at Mexican ranchos like Rancho Cañada de Santa Ana.[64] Beyond this evidence of wool combing for wages, there is no documented occurrence of Native people embracing the practice outside the missions.

In sum, California Indians did not develop loom weaving into an art form. There is no documented tradition of California Indians actively passing down knowledge of loom weaving or preserving loom-made textiles during or after the mission era. While pressure to abandon ancestral ways meant California Indian practices like dances and regalia-making went dormant for some communities, basket weaving was one practice that continued for missionized tribes until about the 1930s. It is an honor for daughters and granddaughters to learn basket weaving from their mothers and grandmothers. The women who learned loom weaving at the missions had a totally different experience: they learned from foreign men who were not invested in helping the weavers develop their own styles, but rather suppressing Native customs and beliefs.

Conclusion

California Indians could have reworked loom weaving by adapting it to their own practices and incorporating basket patterns or other culturally significant designs, but there is no evidence to indicate they did. Basketry reached the status of art within California Indian communities that loom woven textiles never did. Because California Indians rejected loom weaving, it never achieved the prestige of a practice like basket weaving honed over generations. Casting basketry as a craft denies its immense cultural value for Native people. Loom weaving could more reasonably be placed in this category, for it garnered the attention of neither European collectors nor skilled California Indian weavers. Emily Moore has pointed out in her study of Alaska Native arts and crafts that Alaska Natives “have pushed for art as the preferential term” to craft in state legislation.[65] No policies existed to categorize or authenticate California Indian art in the eighteenth century, and even if they did, it is unlikely California Indians would have had any input. I would like to think the ancestors would appreciate the distinction of their basketry as art, even if it comes over two centuries later.

Yve Chavez is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Oklahoma

[1] By focusing on the late eighteenth century context, I problematize Hamlin’s seeming equation of loom weaving and basketry, which was most likely based on early twentieth-century conceptions rooted in the “Arts and Crafts” movement.

[2] John Paul Rangel, “Mapping Indigenous Space and Place,” in Making History: IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, ed. Nancy Marie Mithlo (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2020), 71.

[3] Elissa Auther, String, Felt, Thread: The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), xv.

[4] Auther, String, Felt, Thread, xxx.

[5] Molly Lee, “Tourism and Taste Cultures: Collecting Native Art in Alaska at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” in Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, ed.Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 273.

[6] Elizabeth Hutchinson, The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890–1915 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 7.

[7] I borrow antimodern from Lee’s description of the “antimodernism” of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Lee, “Tourism and Taste,” 273.

[8] In American Indian Basketry, Otis T. Mason referred to basketry as “craft,” specifically a “woman’s craft.” Otis T. Mason, American Indian Basketry (New York: Dover, 1988), 46, 432. In his study of craft, Glenn Adamson begins by stating that basketry is a craft that “has always been with us.” Glenn Adamson, The Invention of Craft (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), xiii.

[9] The textiles, loom, spinning wheels, and weaving tools that appear in Mission La Purísima’s weaving room are likely twentieth-century reproductions. It is unspecified if any of the display items are original to the mission era. Susan Hector writes that “of the three spinning wheels at La Purisima, two were made by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) around 1939, based on a spinning wheel housed at the Santa Fe Museum in New Mexico.” Susan M. Hector, “Spanish Colonial Spinning Wheels in San Diego, California, The Spinning Wheel Sleuth 91 (January 2016): 7. Despite appearing in inventories from the mission era, the original looms and other weaving devices from the missions have not been preserved.

[10] Stephen W. Hackel, Children of Coyote, Missionaries of Saint Francis: Indian-Spanish Relations in Colonial California, 1769–1850 (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 388; Carey McWilliams, Southern California Country: An Island on the Land (New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1946), 37; Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016),35.

[11] Various studies have discussed California Indian population statistics, including Madley, American Genocide, 555–556n2. Benjamin Madley, “Understanding Genocide in California under United States Rule, 1846–1873,” Western Historical Quarterly 47, no. 4 (Winter 2016): 449–461. Gary Clayton Anderson, “The Native Peoples of the American West: Genocide or Ethnic Cleansing?” Western Historical Quarterly 47, no. 4 (Winter 2016): 418–422.

[12] Readers interested in seeing the location of culture regions can explore the Digital Atlas of California Native Americans: https://nahc.ca.gov/cp/

[13] William McCawley, The First Angelinos: The Gabrielino Indians of Los Angeles (Banning: Malki Museum Press, 1996), 117.

[14] Lowell John Bean and Charles R. Smith, “Gabrielino,” in Handbook of North American Indians, V. 8, ed. Robert F. Heizer(Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 541.

[15] Bean and Smith, “Gabrielino,” 541.

[16] Robert F. Heizer, “The California Indians: Archaeology, Varieties of Culture, Arts of Life,” California Historical Society Quarterly 41, no. 1 (March 1962): 6; Reid, The Indians of Los Angeles, 12.

[17] Heizer, “The California Indians,” 6.

[18] Arthur Woodward, “Introduction,” in Juan Vizcaíno, The Sea Diary of Fr. Juan Vizcaíno in Alta California 1769, trans. and ed. Arthur Woodward (Los Angeles: Dawson Books, 1959), xxix-xxx.

[19] Examples of objects Hewett collected can be found in the British Museum collection. I discuss Hewett’s collection in Yve Chavez “California Indian Basket Weavers, Spanish Imperialism, and Eighteenth-Century Global Networks,” in Material Cultures of the Global Eighteenth Century: Art, Mobility, and Change, eds. Wendy Bellion and Kristel Smentek (London: Bloomsbury, 2023), 218–220.

[20] Archibald Menzies, “Archibald Menzies’ Journal of the Vancouver Expedition,” ed. Alice Eastwood, California Historical Society Quarterly 2, no. 4 (January 1924), 324. In North America, the word osier refers to dogwood. The hat that Menzies saw would have been made from juncus, bulrush or sedge, which are native to the Chumash homelands.

[21] Ralph Shanks, California Indian Baskets: San Diego to Santa Barbara and Beyond to the San Joaquin Valley, Mountains and Deserts (Novato: Costaño Books, 2010): 113.

[22] Shanks, California Indian Baskets, 93.

[23] Shanks, California Indian Baskets, 16, 17.

[24] Norman Gabel and James Deetz found “asphaltum with basketry impressions” within the living quarters at Mission La Purísima Concepción. Kaitlin Brown, and Shyra Liguori, “Rediscovering Lost Narratives: The Hidden Cache of a High-Status Indigenous Family at Mission La Purísima Concepción and its Significance in California History,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology (December 2023): 9.

[25] I examine six of these baskets at length in my book, Indigenizing California Mission Art and Architecture (Seattle: University of Washington Press, forthcoming, expected Spring 2025).

[26] José Señán, The Letters of José Señán, O. F. M. 1796–1823, trans. Paul D. Nathan, ed. Lesley Byrd Simpson (Ventura: Ventura County Historical Society, 1962), 68.

[27] Zelia Nuttall, “Two Remarkable California Baskets,” California Historical Society Quarterly 2, no. 4 (January 1924): 341; Janice Timbrook, “Six Chumash Presentation Baskets,” American Indian Art Magazine 39, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 53.

[28] Raúl A. López and Christopher L. Moser, Rods, Bundles & Stitches: A Century of Southern California Indian Basketry (Riverside: Riverside Museum Press, 1981), 5; Sherrie Smith-Ferri, “Weaving a Tradition: Pomo Indian Baskets from 1850 through 1996 (Ph.D. diss., University of Washington, Seattle, 1998), 67.

[29] I discuss the history of basket weaving in Southern California at length in a separate publication. See Yve Chavez, “Basket Weaving in Coastal Southern California: A Social History of Survivance,” Arts 8, no. 3 (2019): 1–15. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/8/3/94.

[30] Dr. Hiram Reid wrote that “To save expense of dying, the wools were cleaned and spun separately, then mixed in the weaving, making salt-and-pepper cloth, and sometimes black and white barred or striped goods, etc.” History of Pasadena (Pasadena: Pasadena History Company, 1895), 350.

[31] Webb argues that loom weaving had been introduced “some twenty years before this time.” Webb, Indian Life, 210.

[32] Robert Archibald, The Economic Aspects of the California Missions (Academy of American Franciscan History, Washington, D.C., 1978), 34.

[33] Junípero Serra, Writings of Junípero Serra, V. II, ed. Antoníne Tibesar(Washington: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1955), 281.

[34] Archibald, Economic Aspects, 50.

[35] Serra, Writings, V. II, 207–209.

[36] Albert P. Lacson, “Making Friends and Converts,” California History (San Francisco) 92, no. 1 (2015): 16.

[37] Zephyrin Engelhardt, San Diego Mission (The James H. Barry Company, San Francisco, 1920), 147.

[38] Engelhardt, San Diego Mission, 147.

[39] Bancroft’s publications on California history were based on information he gathered, with the help of assistants, from primary sources and secondary publications on California. His publications are recognized for representing a biased perspective and not consistently credible. He wrote Hubert Howe Bancroft, the Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, V. XVIII: History of California, V. I 1542–1800 (San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft & Co, 1884), 658.

[40] For more information about the gendered occupations Native peoples held at the missions, see Steven W. Hackel, Children of Coyote, Missionaries of Saint Francis: Indian-Spanish Relations in Colonial California, 1769–1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 282–285.

[41] Marguerite Eyer Wilbur, ed., Vancouver in California 1792–1794 (Los Angeles: Glen Dawson, 1951), 21.

[42] I discuss the work of a Chumash sculptor in my book, Indigenizing California Mission Art and Architecture (Seattle: University of Washington Press, forthcoming). For more on the Royal Academy of San Carlos, see Manuel Toussaint, El Arte Colonial en Mexico (México: Imprenta Universitaria Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1948).

[43] Wilbur, ed., Vancouver in California, 22.

[44] Georg Heinrich Langsdorff, Langsdorff’s Narrative of the Rezanov Voyage to Nueva California in 1806, ed. Thomas C. Russell (San Francisco: Thomas C. Russell, 1927), 55–56.

[45] Maynard Geiger, translator, As the Padres Saw Them: California Indian Life and Customs as Reported by the Franciscan Missionaries, 1813–1815 (Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library, 1976), 147, 148, 150, 153.

[46] Geiger, As the Padres Saw Them, 148, 150.

[47] Geiger, As the Padres Saw Them, 149.

[48] Geiger, As the Padres Saw Them, 147.

[49] Geiger, As the Padres Saw Them, 147, 148.

[50] Geiger, As the Padres Saw Them, 149.

[51] John Muir, “Wild Sheep of California (1874),” in John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes, 1986 (Muir articles 1866–1986), (unpublished manuscript), 80. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmb/80

[52] Webb, Indian Life, 208; Susan M. Hector, “Textile Production and Use at Mission San Diego de Alcala 1769–1834,” Center for Research in Traditional Culture of the Americas, accessed January 8, 2024, https://critca.org/traditional-textile-production-program/textiles-at-mission-san-diego-de-alcala-1769-1834/

[53] Geiger, As the Padres Saw Them, 150.

[54] Geiger, As the Padres Saw Them, 148. It is unclear what was meant by the clothing of the gente de razón. For more information on clothing that gente de razón wore, see Barbara L. Voss, The Archaeology of Ethnogenesis: Race and Sexuality in Colonial San Francisco (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2015).

[55] Francis F. Guest, “Cultural Perspectives on California Mission Life,” Southern California Quarterly 65, no. 1 (Spring 1983): 44.

[56] On “shirting,” see Archibald, Economic Aspects, 148; E. Philpott Mumford discusses Henríquez introducing cotton sheet weaving at Missions San Gabriel and San Luis. See “Early History of Cotton Cultivation in California,” California Historical Society Quarterly 6, no. 2 (1927): 162.

[57] Mumford, “Early History,” 162.

[58] Mumford, “Early History,” 159.

[59] Francisco Palóu, Historical Memoirs of New California, V. I, ed. Herbert Eugene Bolton (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1926), 189.

[60] Eugène Duflot de Mofras, Duflot de Mofras’ Travels on the Pacific Coast, V. I, trans. and ed. Marguerite Eyer Wilbur(Santa Ana: The Fine Arts Press, 1937), 172.

[61] Webb, Indian Life, 213.

[62] Webb notes that of the missions who kept records on the matter, the number of looms recorded at a given mission hovered around four. Webb, Indian Life, 210–211.

[63] Hector, “Textile Production.”

[64] George Curley, “Indian Working Arrangements on the California Ranchos, 1821–1875 (PhD Diss., UC Riverside, 2018), 19.

[65] Emily Moore, “The Silver Hand: Authenticating the Alaska Native Art, Craft and Body,” The Journal of Modern Craft 1, no. 2 (July 2008): 209.

Cite this article as: Yve Chavez, “Eighteenth-Century Loom and Basket Weaving at the California Missions,” Journal18, Issue 18 Craft (Fall 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7537.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.