Ellen Siebel-Achenbach

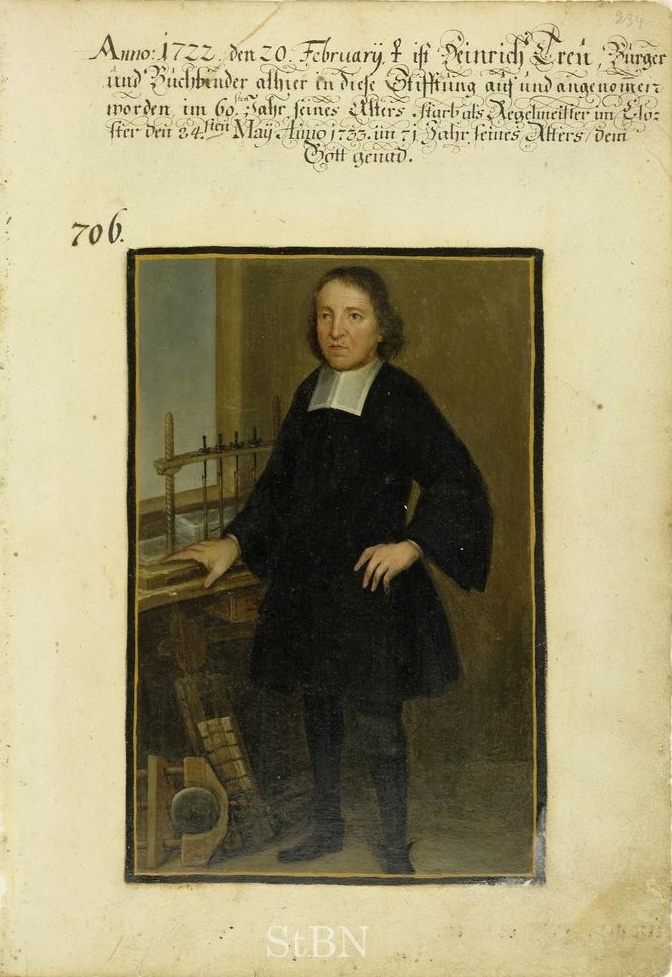

In his full-length portrait, the eighteenth-century bookbinder Heinrich Treu (ca. 1662–1733) stands beside a workbench, his hand resting on a large sewing frame whilst a lying press with three books and an edge plough sit at his feet (Fig. 1). Painted in 1722, the portrait is included in the second volume of the Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen (hereafter the “house books,” Mendel II), a series of manuscripts that depict members of prominent trade fraternities in Nuremberg.[1] Each house book portrait is accompanied by a biographical inscription, and most include detailed depictions of the member’s products and tools. Treu’s portrait thus offers not only a rare full-length depiction of a bookbinder but also information on the bookbinding tools of the period. My focus here is on the edge plough, a planing tool designed to trim the edges of a book block. Treu’s portrait is the first visual depiction of a circular-bladed version of the tool in Nuremberg. Offering a clear view of the blade, body boards, and connecting rods, it provides the only information we have concerning the plough’s local design and use.[2]

In this essay, I will discuss my recent experimental reconstruction of Treu’s edge plough. Beyond a detailed account of the practical processes of reconstruction, I provide a theoretical grounding for the project. The plough is a mediator between different materials (wood, paper, and metal) as well as makers and products. Reconstruction offers opportunities to recover these relationships through engagement with the physical and functional qualities of the tool that are inaccessible in the portrait. Due to the absence of material evidence, my reconstruction differs from the established methods of experimental archaeology: both my material and some design decisions were informed by a combination of surviving eighteenth-century tools and other artistic representations of the plough.[3] However, my plough reconstruction follows such experimental methods in using “hands-on” making and testing as an interpretative gateway to access Treu’s creative actions in bookbinding. As in experimental archaeology, thinking with the tool during the creative process fosters a multi-sensory knowledge of the object through material problem-solving.[4]

The Edge Plough and the House Books

Adapted from wooden joinery plough planes, edge ploughs offer a smoother sideways cut than the medieval draw knife, an earlier book trimming tool that often left distinctive scoring marks. While ploughs can shave vellum book blocks, the tool was developed to facilitate the increased use of paper in bookbinding during the sixteenth century. Whereas vellum could easily withstand the draw knife’s full (head to tail) cuts, the gentler individual page-cuts of the plough suit the more delicate structure of paper.[5]

Nuremberg holds both the earliest visual and textual evidence for the plough, including two beschneidehobel (trimming planes) listed in a 1530 bookbinder’s inventory and a depiction in Jost Amman’s Das Ständebuch (1568).[6] Treu’s elaborate plough is drastically different from Amman’s simple form, featuring guiding rods, angled body pieces that are fitted to his lying press, and a circular blade.[7]

The edge plough in Treu’s portrait also features a more intricate construction than those depicted in the other bookbinder portraits of the house books. Dating from the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries, the manuscript series chronicles the history and membership of the Mendelian (1388–1806) and Landauer (1511–1806) trade fraternities.[8] Treu was the Regelmeister (“rule master”) of the Mendelian fraternity, and his portrait is unusual compared to those of the other eighteenth-century bookbinders. For example, the compositions of later portraits of Leonhard Glaser (1753) and Johann Schönberger (1756) contrast with Treu’s: both men are painted from the waist up in a nondescript interior space. Whereas Glaser holds a lying press with a sewing frame in the background, these tools are replaced by finished books in Schönberger’s portrait. Treu is the only bookbinder painted with a plough, and depictions of his tools are more detailed than Glaser’s, making his portrait an ideal source for my reconstruction.

Reconstructing the Treu Edge Plough

Despite the greater detail of Treu’s tools in comparison with the other bookbinder portraits of the house books, the manuscript painter’s intention was not technical accuracy. The materials used in the plough thus remain uncertain. In addition, the tool’s dimensions can only be estimated relative to Treu’s body, and the top angle of the plough is not depicted in the portrait. Further complicating the reconstruction is the lack of surviving ploughs or archaeological remains from eighteenth-century Nuremberg. Despite the city’s longstanding tradition of technical tool illustration, formal plans are likewise nonexistent.[9] This proved particularly problematic in designing the plough’s top components, threaded rod, and handle placement, each of which are not captured in the painting.

While working from an extant plough would have offered more accuracy in the reconstruction, the limitations of the portrait encouraged reflection on the relationship between the plough and the body of its operator (both Treu and modern makers), as well as reflection on the material relationships between different tools in the bookbinding process.[10] In this sense, it is useful to draw a distinction between “replication” and “reconstruction.” Whereas “replica” suggests an attempt to exactly reproduce a plough (only possible from an extant model), “reconstruction” is centred on reproducing creative processes. As a result, it requires a more embodied experience of the tool’s physical form in order to propose possible solutions to the portrait’s absent components. The reconstruction method thus offers opportunities to think critically with the tool in pursuit of the “author-practitioner’s worldview of matter and skill,” as investigated in studies such as Columbia University’s Making and Knowing Project.[11] As modern makers are distanced from the apprentice-based learning systems of Treu’s period, the “reverse-engineering” emphasis of reconstruction can offer insights into craft processes by combining visual evidence with personal trade knowledge.[12]

The embodied knowledge of experimental reconstruction relies on sustained “hands-on” interaction with the plough during both its creation and use to make books: the tangible tools of bookbinding are inextricably linked to their intangible making skills and actions.[13] Tools, by their nature, are defined by tactility, thus constituting a distinct category from the objects that they create. As Hannah Arendt notes, these hand processes are embedded in their design:

Works of art are thought things, but this does not prevent their being things… What actually makes the thought a reality and fabricates things of thought is the same workmanship which, through the primordial instruments of the human hands, builds the other durable things of the human artifice.[14]

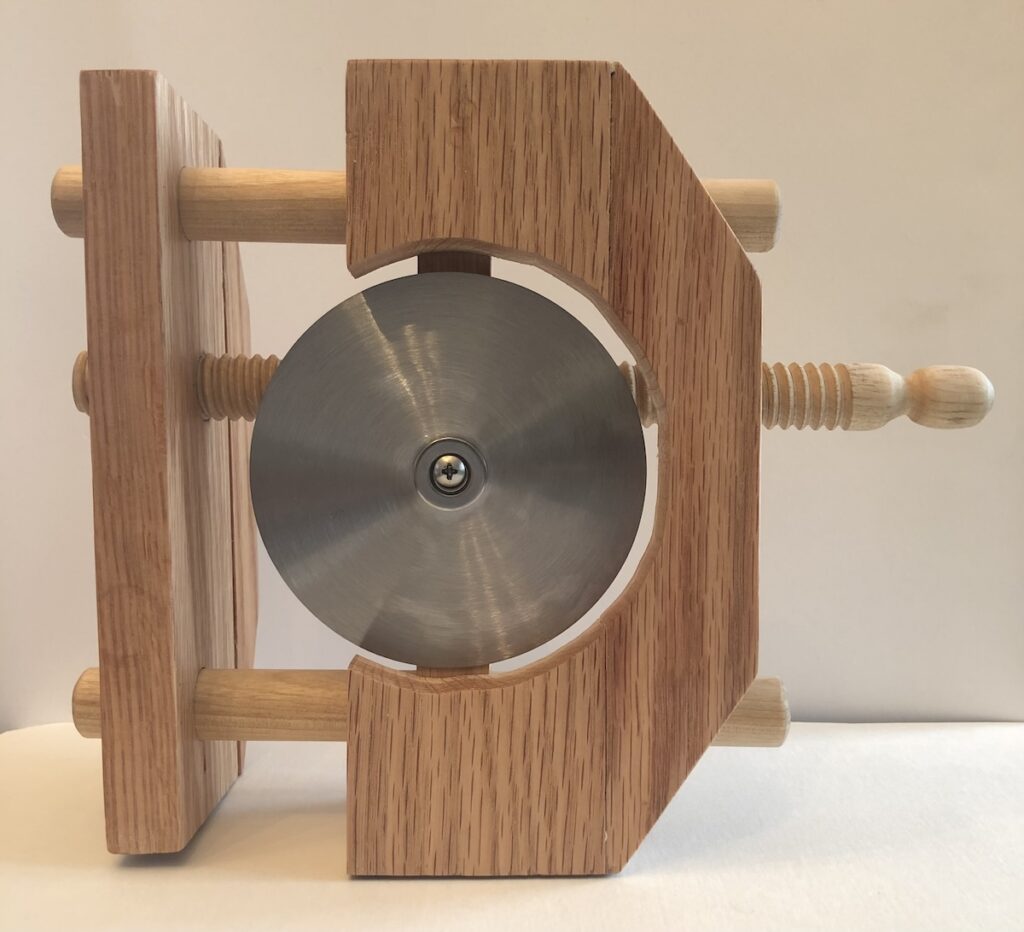

Compared to contemporary technologies, hand tools thus retain a sense of permanence through the continuity of historical making processes.[15] To match this permanency, my reconstruction was created almost exclusively with traditional tools (Fig. 2). Although some electric tools were used, the fundamental mechanism of these machines closely resembles that of their hand tool equivalents (including an electric lathe).

The use of hand tools in experimental reconstruction also offers insight into the relationship between the materials and the maker. In the case of the plough, hand drilling and threading gave me greater control over the angle and pressure of the tool in order to avoid cracks/breakout (ripped grain along the wood’s face). In turn, I was able to carefully position and adjust each hole in consideration of the wood’s unique grain structures.[16] Hand tools aided my understanding of the same constraints, both of the individual components and of the tool as a whole, with which the maker of Treu’s plough would have been familiar.[17]

Materials

Although it is impossible to determine the materials of Treu’s edge plough from his portrait alone, the majority of surviving eighteenth-century bookbinding tools were made of oak, a hardwood that offered both beauty and durability (including water resistance) through its fine grain patterns.[18] I primarily used red oak (with some poplar) in my reconstruction, a species native to Nuremberg’s surrounding forests that would have been easily accessible to Treu’s tool maker.[19]

In the eighteenth century, green oak would have been naturally seasoned through the traditional stack drying method. This process could take up to two years because of the wood’s dense grain and would likely have been completed by holzhackers (wood chippers). It is probable that the holzhackers were also responsible for preparing and planking the log.

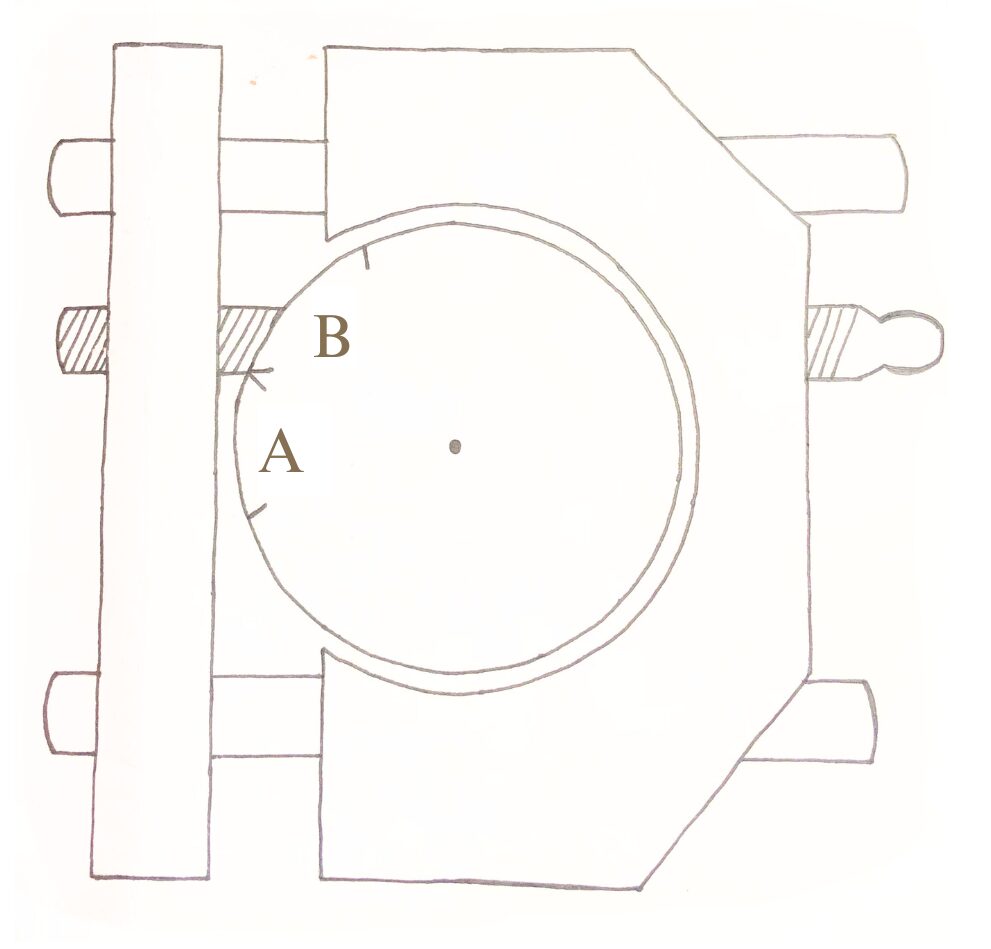

I began my reconstruction with oak planks and then planed the surface of the lumber smooth before cutting the main components of the tool with small rip and coping saws (for rounded cuts), the same tools that Treu’s maker would have used. These reconstructed parts include two rectangles (2 3/8 x 7 1/2 inches) with trapezoidal tops (1 3/8 x 7 1/2 inches) and a rectangular connecting bar (1 3/8 x 7 1/2 inches, not visible in the house bookillustration), each estimated in size relative to Treu’s body (Fig. 3). As the joining methods of the tool are not depicted in the portrait, I have chosen to use dowel pegs, a common eighteenth-century support formed through a dowel plate.

Threaded Rod

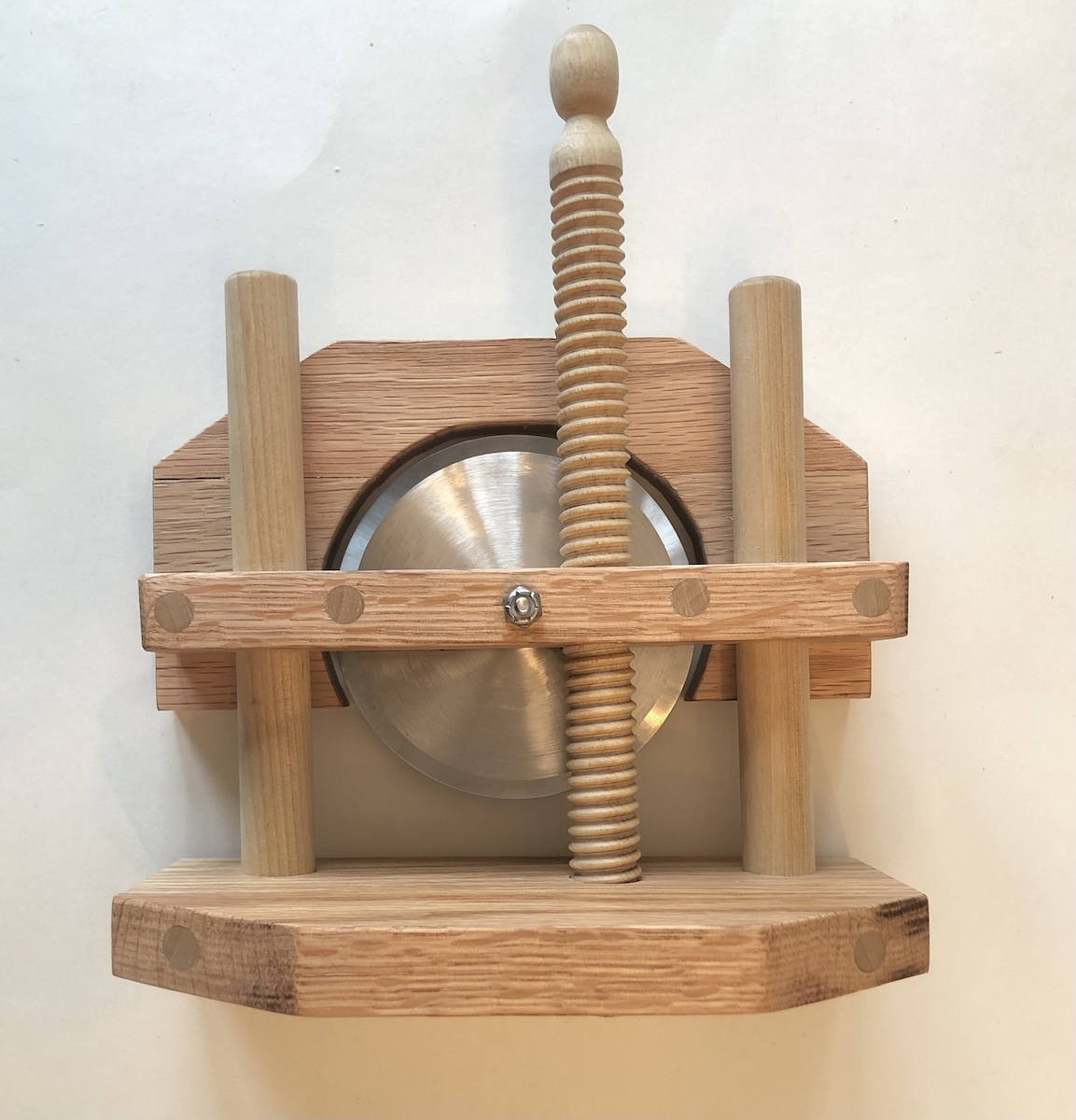

While it is possible that the plough’s central rod was threaded on a lathe, the thread box and tap die method had been used in Nuremberg since at least 1505 and was more efficient.[20] I used the twisting thread box technique on a 3/4-inch oiled poplar dowel, a coating that encourages a smooth thread and avoids breakout (Fig. 4).[21] The corresponding hole was clamped to a spare board (likewise to minimalize breakout) before being drilled with a 5/8-inch brace bit and threaded with a 3/4-inch tap die, as the size difference allows for more pronounced threads and a tighter fit.

Handle

It is unclear whether the visible end of the threaded rod in Treu’s portrait is the edge plough’s handle, as the tool is cut off in the painting. However, the feature follows the common placement of the handle above plough blades and is similar to the construction of the tool illustrated in Abraham à Sancta Clara’s Etwas für Alle (1699). The form is also similar to surviving nineteenth-century German handles, which are characterized by rounded ends, thin decorative shanks, and short dimensions.[22]

Treu’s handle has a balled (rounded) end rather than a spherical form. Although it is possible that the handle was turned separately and attached to the plough, its small size indicates that it was likely turned from the rod’s wood to ensure stability. For sizing, I chose to thread the rod before mounting it on the lathe and turning the form with a bowl gouge and skew.

Blade

The earlier Etwas für Alle plough features an almost unmanageably large circular blade when compared to Treu’s tool. Round blades appear to have been an early seventeenth-century invention and would have been forged by a bladesmith (likely distinct from the tool maker).[23] They required less sharpening time to offer precise trimming: after the initial contact cut, the rounded form has a second cutting arc in its wake to create a “glossy” finish (Fig. 5).[24] These blades are not rotary and would only be moved once manually loosened to adjust the sharpening edge.[25] They are drastically different from the pointed blade plough, a form that became dominant from the late eighteenth century onwards.

It is unclear how Treu’s blade is attached to the plough, as the circle features no holes and the top of the tool is not visible. In lieu of a rounded plane blade, I used a pizza blade, bevelled at 15 degrees, and attached it with a nut and bolt mechanism to the connecting bar.

Rods

The shading on the guiding rods in the house book plough suggests that their form was cylindrical. Absent in Amman’s sixteenth-century woodcut, these rods were a recent addition to the tool and functioned to stabilize it during adjustment of the threading depth. Although Treu’s dowel rods are not unusual for the period, the majority of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century versions of the plough feature squared rods in a mobile mortise and tenon joint (a sturdy, yet difficult, form to create). For instance, the deconstructed edge plough in the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot (1771) clearly features squared rods.

While my dowel rods appear larger than the central threaded rod because of the deductive threading process, they share the same 3/4-inch diameter (Fig. 6).

Finishings

I finished the reconstruction by balling the ends of the rods, rounding the sharp edges to facilitate easy handling. A coat of beeswax polish cut with linseed oil was also applied for aesthetic purposes, as well as offering a “gliding” quality on the lying press.[26]

Function

The reconstructed edge plough functions well, resulting in a crisp edge to the book blocks. When compared to an earlier reconstruction of Amman’s plough I produced, Treu’s tool is easier to adjust (in depth) and creates a smoother finish through the dual cutting arch of the circular blade. Indeed, the edge it creates is almost smooth enough to be gauffered and gilded without further treatment of the block.[27] My only complaint with the reconstruction is that the handle is too small to be comfortable for frequent use, facilitating neither a firm grip nor the simple forward and backward motions of ploughing.

Although the plough reconstruction is not an exact replica of Treu’s original, it provides insight into how the tool functioned in his making processes. For example, the reconstruction’s dual cutting arch allows us to consider Treu’s movements in creating the smooth edges of the ploughing process. The reconstruction of the tool thus offers insight into the embodied experience of bookbinding between historical and modern makers, its traditions steeped in tactile engagement to “train the eye in the interpretation of historical objects.”[28]

Conclusion

My experimental reconstruction offers material and functional interpretations of the house book edge plough that extend beyond the reach of its visual depiction alone. As a result, while the tool remains grounded in its original eighteenth-century space and temporality, modern interactions with the reconstruction encourage new interpretations of its mediating position between objects and makers, materials and trades, and tools and products. The reconstructed edge plough thus acts as a gateway to both material engagement and the relationship between Nuremberg’s intangible and tangible bookbinding heritage in the eighteenth century.

Ellen Siebel-Achenbach recently received her MA in art history at the University of Toronto and has begun studies in heritage architecture restoration at the Willowbank School of Restoration Arts in Queenston, Ontario

[1] Unlike guilds, these fraternities offered membership to craftsmen of diverse trades. The name of the manuscripts translates to “House Books of the Nuremberg Twelve Brothers Foundations.”

[2] No records survive indicating whether the plough was made by Treu or a specialist tool maker.

[3] Similar reconstruction projects are often carried out by woodworking reenactment groups, including the St. Thomas Guild of Nimwegen in the Netherlands. Their hand plane reconstructions are based on a combination of medieval visual and archaeological sources with surviving nineteenth-century examples. See “The Medieval Toolchest: The Plane (Part 2),” St. Thomas Guild – Medieval Woodworking, Furniture, and Other Crafts, October 15, 2014, https://thomasguild.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-medieval-toolchest-plane-part-2.html.

[4] Christina Souyoudzoglou-Haywood and Aidan O’Sullivan, “Introduction: Defining Experimental Archaeology: Making, Understanding, Storytelling?,” in Experimental Archaeology: Making, Understanding, Story-Telling: Proceedings of a Workshop in Experimental Archaeology, ed. Souyoudzoglou-Haywood and O’Sullivan (Summertown, Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., 2019), 1–4, 2.

[5] Nuremberg was the first city north of the Alps to have a paper mill. Dard Hunter, Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft (New York: Dover Publications, 1978), 231.

[6] J. A. Szirmai, The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding (Abingdon: Routledge, 1999), 197–198.

[7] A form associated with German and Scandinavian bookbinding traditions. See Tom Conroy, “The Round Plough,” Binders’ Guild Newsletter XI:5 (1988), https://cool.culturalheritage.org/byorg/abbey/an/an13/an13-3/an13-314.html.

[8] Although early portraits likely served a memorial function, Treu’s was painted upon his entry into the Mendelian fraternity. Both foundations ceased operations after Nuremberg lost its status as a free imperial city in 1806.

[9] See the Martin Löffelholz Codex (1505), Jagiellonian Library, Krakow, http://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=258834.

[10] Barry Molloy, “Crafting Prehistoric Bronze Tools and Weapons: Experimental and Experiential Perspectives,” in Experimental Archaeology, ed. Souyoudzoglou-Haywood and O’Sullivan, 15–26; Souyoudzoglou-Haywood and O’Sullivan, “Introduction,” 2.

[11] Tillmann Taape, Pamela H. Smith, and Tianna Helena Uchacz, “Schooling the Eye and Hand: Performative Methods of Research and Pedagogy in the Making and Knowing Project,” Ber. Wissenschaftsgesch 43 (2020): 323–340 (p. 324).

[12] Molloy, “Crafting Prehistoric Bronze Tools and Weapons,” 15–16.

[13] For a discussion of this relationship in the context of heritage architecture, see Sharon Macdonald, “Reassembling Nuremberg, Reassembling Heritage,” Journal of Cultural Economy, 2, no. 1-2 (2009): 117–134, https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350903064121.

[14] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 168–169.

[15] Arendt, The Human Condition, 150–151.

[16] Molloy, “Crafting Prehistoric Bronze Tools and Weapons,” 18.

[17] Molloy, “Crafting Prehistoric Bronze Tools and Weapons,” 24.

[18] Tom Conroy, Bookbinders’ Finishing Tool Makers, 1780–1965 (New Castle: Oak Knoll Press, 2002), 220.

[19] “Key Figures on Forest Genetic Resources,” Bundesanstalt für Landwirtschaft und Ernährung, https://www.genres.de/en/sector-specific-portals/trees-and-shrubs/what-is-it-about/key-figures.

[20] The Löffelholz Codex includes designs for a threaded reamed auger and thread box (fols. 4v-5r), Jagiellonian Library, Krakow, http://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=258834.

[21] I substituted poplar dowels for the rods because the fine grain of oak often results in breakout during threading.

[22] Conroy, Bookbinders’ Finishing Tool Makers, 218–219.

[23] A possible round plough blade is depicted in Nicasius Florer’s house book portrait of 1614 (Landauer I fol. 85v). Another seventeenth-century example from the Netherlands can be found in Dirck de Bray’s A Short Instruction in the Binding of Books (1658), which includes a sketch of a round bladed plough. See Dirck de Bray, A Short Instruction in the Binding of Books [1658], ed. Koert van der Horst and Clemens de Wolf (Uithoorn, the Netherlands: Atelier de Ganzenweide, 2012), 124-5.

[24] Conroy, “The Round Plough.”

[25] When combined with the movement of the plough, a rotary blade would create an uneven edge cut.

[26] Beeswax and linseed oil (often mixed with turpentine) were common ingredients in varnish in eighteenth-century furniture making. Several repetitions of the polishing and brushing process were required to build up a rich color and smooth surface. For the English context, see Herbert Cescinsky, English Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, vol. III (London: George Routledge and Sons Ltd., 1911), 352.

[27] Conroy, “The Round Plough.”

[28] Taape, Smith, and Uchacz, “Schooling the Eye and Hand,” 323.

Cite this article as: Ellen Siebel-Achenbach, “Bookbinding in Eighteenth-Century Nuremberg: Reconstructing an Edge Plough from the Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen,” Journal18, Issue 18 Craft (Fall 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7482.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.