Stacey Sloboda

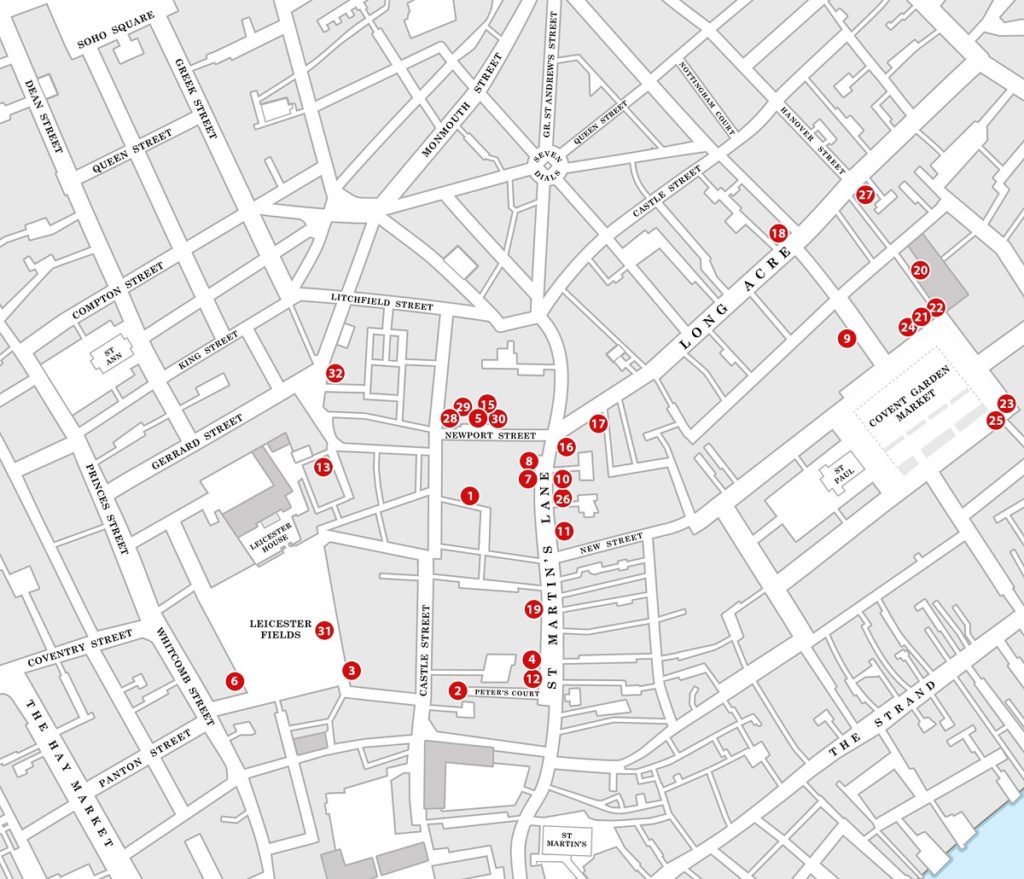

Perched inside a window box, an artist in a loose smock and a skullcap bends over his unseen work, the head of sculpted putti peering over his shoulder (Fig. 1). The artist’s back is turned to an urban neighborhood dense with brick and plaster terraced buildings, older timber-framed houses, and leafy back yards. A single shop sign boldly announces the location of John Noble’s Circulating Library, where for three shillings quarterly, one could borrow from Noble’s catalog of over 5,000 books, nearly 1,000 of them in French (Fig. 2, map point 1). The inclusion of Noble’s huge shop sign in Thomas Sandby’s watercolor makes it possible to identify it as an image of St. Martin’s Court, an L-shaped street that joined Leicester Fields to St. Martin’s Lane in London’s West End in the eighteenth century.[1]

This remarkable image combines the representation of art making and of place, familiar subjects in Sandby’s work, though usually not shown together. As Sandby’s image suggests, the neighborhood around St. Martin’s Lane was brimming with artists and cultural resources. In a brief but suggestive article published in 1966, the historian Mark Girouard described the neighborhood as made up of “two worlds”—those of fine artists and artisans.[2] The surrounding Covent Garden had been a center for ambitious artists since the middle of the seventeenth century, and the St. Martin’s Lane Academy (map point 2), re-opened in 1735 by William Hogarth (map point 3), is generally recognized as an important, if not fully understood, site of artistic training and community for two generations of British painters, sculptors, and architects.[3] These artists included Joshua Reynolds, whose first London address was in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where he was an apprentice in Thomas Hudson’s portrait studio. Reynolds notably left that apprenticeship before his seven-year term had expired, alternately returning to his native Plymouth and taking residence in a building just around the corner from the Academy in St. Martin’s Lane (map point 4), setting off for Italy, and then returning to St. Martin’s Lane before moving around the corner to Newport Street (map point 5), and then finally taking up residence in the grand townhouse for which his studio was famous in Leicester Square in 1760 (map point 6).

In 1754 the architect James Paine (map point 7) rebuilt two houses in St. Martin’s Lane and rented rooms in the back house to the book illustrator and engraver Samuel Wale and the architect and writer John Gwynn. Paine built his house immediately next door to Old Slaughter’s Coffeehouse (map point 8). Girouard identified Slaughter’s as the social nexus of the St. Martin’s Lane set, though numerous other coffeehouses, pubs, Freemasons’ lodges, churches, societies, and clubs in the area were also significant gathering places. Directors of the Academy in the 1730s and 40s included the French illustrator and designer Hubert-François Gravelot (map point 9), who also ran a drawing academy in his own house at the sign of the Mortar and Pestle in nearby James Street, which the St. Martin’s Lane Academy either replaced or, more likely, complemented.

The goldsmith George Michael Moser became a principal instructor at the Academy after establishing a rival drawing academy in Salisbury Court in 1735. Moser also lived in James Street, possibly at or near the same address as Gravelot, until he moved in 1737 to Craven Buildings off Drury Lane. In 1743, the St. Martin’s Lane Academy director and painter Francis Hayman purchased the lease at No. 8 Craven Buildings immediately next door to the Mosers and lived there until 1760, when he moved to the St. Martin’s Lane house that Reynolds had previously occupied (map point 4). The sculptor Louis François Roubiliac was likewise closely associated with the St. Martin’s Lane Academy. From around 1738, he lived in Peter’s Court in part of the building occupied by the St. Martin’s Lane Academy (map point 2) and, in 1741, moved to a large house in St. Martin’s Lane near the corner of Long Acre (map point 10).

At the same time, St. Martin’s Lane and the surrounding neighborhoods of Covent Garden and Soho were replete with the shops of cabinetmakers and upholsterers, carvers, goldsmiths, and print engravers as well as painters, sculptors, engravers, and other creative trades. By mid-century, many of the best-known cabinetmakers and wood carvers of the period lived in St. Martin’s Lane. The cabinetmaker and designer Thomas Chippendale worked with the engraver Mattias Darly in a house in Northumberland Court at the base of St. Martin’s Lane until 1754, when Chippendale published their book, The Gentleman and Cabinet Makers Director, from the sign of the Chair at what is now 60-62 St. Martin’s Lane (map point 11). The location likely appealed to Chippendale because of the notable concentration of ambitious cabinetmakers who operated in and immediately around St. Martin’s Lane. By the 1750s, John Channon (map point 12), Frederick Hintz (map point 13), John Bradburne (map point 14), William Hallett (map point 15), William Vile and John Cobb (map point 16), William and John Linnell (map point 17), and Benjamin Goodison (map point 18) all had cabinetmaking workshops in or directly around the lane.

Recounting some of these social connections, Girouard remarked that “the whole business of the connection between artists and craftsmen at this period deserves further research.”[4] Over fifty years on, Girouard’s observation remains true. The commercial nature of this art world has long been recognized, while the extent to which it was enabled by close geographic proximity and social and professional networks of interrelated trades has not.[5] This short article extends and revises Girouard’s “two worlds” description of St. Martin’s Lane by considering the built environment of the neighborhood to argue that St. Martin’s Lane contained not two separate worlds of art and craft but a single art world of overlapping, collaborative, and competitive networks of creative trades set within a historically and culturally significant urban milieu.[6]

The Art World and Urban Space

Identifying where artists lived and worked is a process of describing a place. But the neighborhood and the art world that inhabited it was also a space, not given but produced.[7] In the absence of an organizing institution such as a government-sponsored academy or a functioning guild system, the neighborhood provided a decentralized institutional structure for the mid-eighteenth-century London art world. This emerged from and continued the well-established tendency of early modern European artisans to cluster geographically in order to draw upon shared resources and clientele and create a distinct identity for themselves and their trade.[8] However, equally operative for this London neighborhood by mid-century was its position in the modernizing cultural economy of eighteenth-century Britain, in which technical and artistic innovation and an enthusiasm for novelty and fashion drove a market-oriented approach to culture of all forms.[9]

The neighborhood was not just a center for the visual arts and luxury retail but also for theatre, cartography, prints, and, to some extent, publishing.[10] A market-based practice of cultural production enabled, or perhaps required, a concentrated urban fabric of independent artists and artisans collaborating and competing outside of centralized institutional structures and traditional forms of patronage. This focus on creative production as a commercial product blurred the still-nascent boundaries between fine and applied arts that many of the neighborhood’s artists were eager to erect. They aimed to do so through the establishment of a Royal Academy that they thought (wrongly) would alleviate the economic imperatives of the commercial art world and provide an intellectual and socially elevated milieu for a select group of fine artists that were conceptually, ideologically, and spatially distinct from the commercial urban art world they inhabited.[11]

The urban environment’s capacity to collectivize meant that a neighborhood could constitute an art world, which depends on shared resources and the ability to exchange ideas through formal and informal social and visual means. In the market-driven art world of mid-eighteenth-century London, this was achieved through private and commercial activity enabled by the neighborhood. London’s strong social organization by neighborhood was governed by overlapping boundaries of parishes and estates and the ordering of neighborhoods by and around the residential squares of Westminster that developed through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[12] Colorshops such as Edward and Martha Powell’s (map point 19) offering ground and mixed pigments freed painters from employing assistants and apprentices for such tasks. Timber yards along the north shore of the Thames, including one immediately to the south of St. Martin’s Lane, meant that furniture and frame makers could outsource the storage of valuable timber.

The scene painting studios of the Covent Garden, Hay Market, and Drury Lane theaters not only provided employment for painters but also offered a physical space for executing larger canvases that would have been impossible in most artists’ house-studios. This was an essential resource for William Hogarth, for instance, when he painted The Pool of Bethesda, his first monumental canvas for the stairwell of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, in 1735, the same year he re-opened the St. Martin’s Lane Academy. Hogarth collaborated with George Lambert, with the assistance of John Inigo Richards, Lambert’s studio assistant, and Hogarth’s godson, and is thought to have painted the massive canvas in Lambert’s scene painting studio at the Covent Garden Theatre (map point 20).[13]

As the Hogarth-Lambert-Richards example suggests, the neighborhood was not just a place with material resources for artists. It was a social space that engendered collaboration among painters of differing skill sets and reputations that was forged through social, spatial, and professional networks.[14] For Hogarth and Lambert, one connective social space was the Sublime Society of Beefsteaks, where artists and patrons gathered monthly in Lambert’s painting studio to drink, eat beef, and converse on the encouragement of contemporary British art and culture. Freemasons’ lodges and French and Anglican churches, coffeehouses, taverns, and even a fire insurance office were other key spaces in the neighborhood for forging social connections.

Mapping the Art World

The first step in tracing the social and artistic connections of the artists and artisans of St. Martin’s Lane has been to identify and locate them, a task not as straightforward as it sounds.[15] As a physical place, the neighborhood was anchored by Covent Garden, a distinguished address since the mid-seventeenth century for artists including Peter Lely and, later in the same house, James Thornhill (map point 21), Godfrey Kneller in the house next door (map point 22), and Louis Chéron (map point 23). In 1731, Christopher Cock (map point 24) established his auction house next door to Thornhill’s house, studio, and occasional drawing academy on the northeast side of the Piazza. Through the mid-eighteenth century, the painting studios of John Ellys, George Lambert (map point 20), Samuel Scott (map point 25), and Richard Wilson carried on the tradition of artists residing around Covent Garden, though its shine had worn off. Some aura of wealth and patronage still emanated around the neighborhood from the London houses of the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland in Charing Cross at the base of St. Martin’s Lane and the Prince and Princess of Wales at Leicester House, crowning the north side of Leicester Square.

Only a tiny fraction of the eighteenth-century buildings in St. Martin’s Lane survives today, leaving little architectural evidence of the built environment. However, the footprint of the street itself is little changed, offering a good sense of its urban scale. St. Martin’s Lane is a serpentine lane that snakes northward from James Gibbs’ splendid parish church, St. Martins-in-the-Fields (1726), to Edward Pierce’s sundial pillar (1694) at the center of the Seven Dials. Today, as it would have in the eighteenth century, it takes about six minutes to walk the entire length of the street. Narrow and densely built along both sides, contact between residents was inevitable. Mapping eighteenth-century residences is complicated by the absence of house numbers and changing or idiosyncratic naming of streets. There was no widespread attempt to assign numbers to houses in London until the last decades of the eighteenth century; even after that, they were piecemeal and changed over time. Particularly in a relatively small street like St. Martin’s Lane and the numerous courts and alleys connected to it, a street name was considered a sufficiently descriptive address, with pictorial shop signs like John Noble’s (Fig. 1) or a reference to a nearby street or landmark sometimes provided, particularly for retail and trades. As a result, modern knowledge of artists’ urban residences in this period is usually generalized to a street or neighborhood, offering little specificity to the social and built environments on the ground.

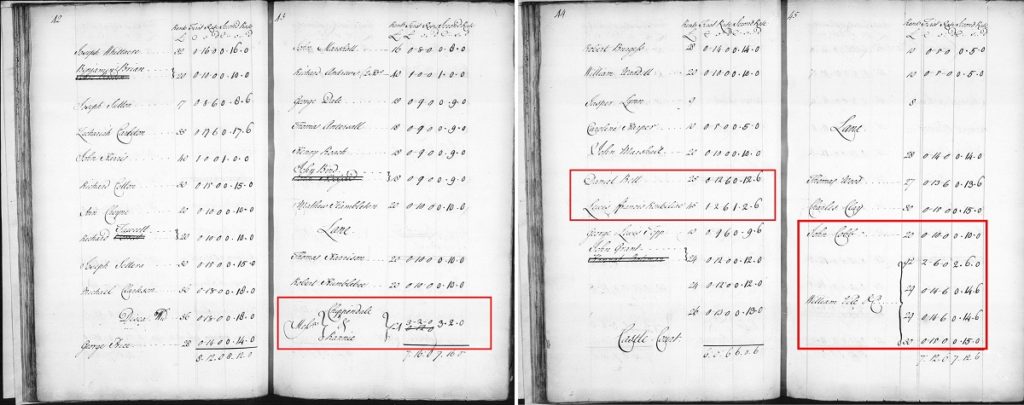

Tradecards, advertisements, first-hand accounts, and letters sometimes provide more clarity (particularly for well-known artists), but the most useful sources for locating subjects within a London street in this period are the Parish Rate Books.[16] Rates (or taxes) were levied upon residents by London’s parish churches for various purposes, from assisting the poor to paying for sewage and road maintenance to funding a night watch. Though they have numerous limitations and elisions, parish rate books provide an astonishingly detailed record of the residents of even the smallest streets in London throughout the eighteenth century.[17] With them, one can track precisely where and when an artist lived, their neighbors, and their property’s relative size and value.

For instance, in pages from the 1756 St. Martin-in-the-Fields Poor Rate Ledger (Fig. 3), the rate taker has walked westward along New Street, then re-joined the east side of St. Martin’s Lane (here, “Lane”) where we find the cabinetmaking workshop of Thomas Chippendale and James Rannie occupying the third and fourth houses on the east side of St. Martin’s Lane just north of New Street. Turning the page, we see that in 1756 Chippendale and Rannie had not yet taken over the third house later associated with their workshop, as it was presumably still being finished by their landlord, the bricklayer and property developer Robert Burgess.[18] Four entries on, we find the house of Daniel Bell (map point 26), described in a 1728 newspaper account as “an eminent cabinet maker.” In 1728, his St. Martin’s Lane workshop was damaged in a fire that consumed “a great quantity of valuable foreign wood lying in his yard for carrying on his business at which he employed several scores of people every day, so that this loss alone is reckoned to amount to some thousands of Pounds.”[19] Though much of what we know about this apparently eminent cabinetmaker is limited to this disaster, the rate books show that he, or perhaps an eponymous son, carried on the business well into the 1750s. Bell’s immediate neighbor, the French émigré sculptor Louis François Roubiliac (map point 10), first appears at this address in 1741. The rate book tells us that it was a large house; Roubiliac paid £45 annually in rent, the highest of any of his immediate neighbors.[20]

The Assembly Line of the Street

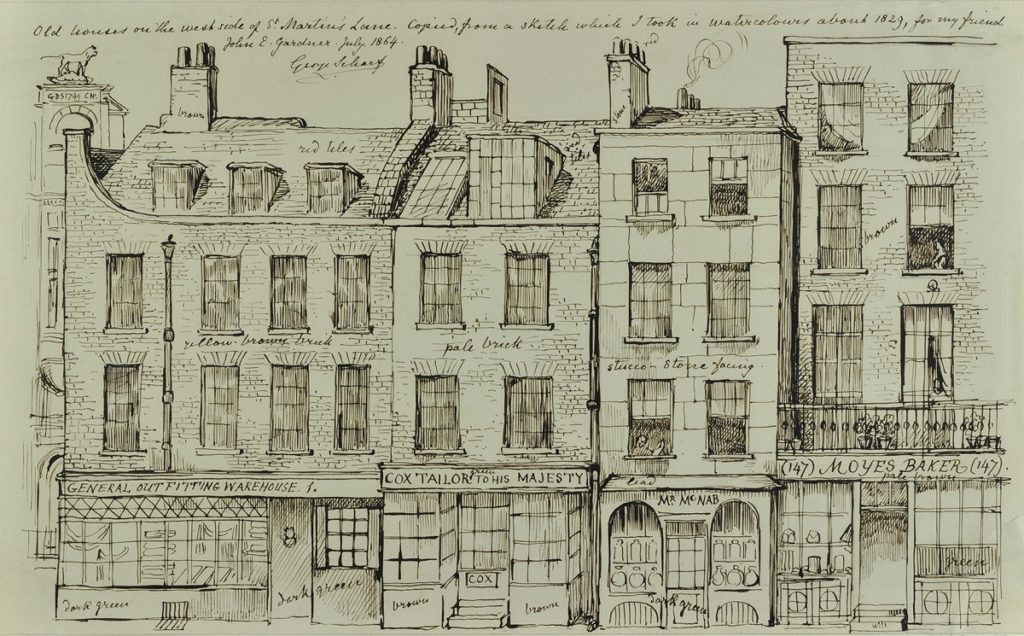

In London in this period, tradesmen, artists, and artisans who operated under their own names usually resided where they worked, with family, apprentices, and sometimes lodgers also occupying the same house. Glass-fronted retail or showroom spaces facing the street were increasingly common, with studios, workshops, offices, and yards at the back, and private rooms for families, apprentices, household staff, and sometimes lodgers on the upper two or three floors. A nineteenth-century sketch by George Scharf of the west side of St. Martin’s Lane offers some sense of what the eighteenth-century street would have looked like (Fig. 4). The style of fenestration, brick and stone flat-fronted facades, angled brick window cornices, and dormer windows or skylights for a garret are typical of the eighteenth-century buildings of the neighborhood. Scharf’s sketch shows more multi-paned and bow-fronted glass windows than there probably would have been in the eighteenth century, and signage along a cornice rather than as painted or sculpted signs projecting off the building is another nineteenth-century feature. Nevertheless, Scharf’s image conveys the street’s mixed residential and commercial character as it existed in the eighteenth century.[21]

It is unlikely that a sculptor like Roubiliac would have had use for a glass-fronted house to display samples of his innovative marble sculptures, but his cabinetmaking neighbors almost certainly did.[22] Returning to the rate books, walking past the narrow entrance to Castle Court, we find the names of the cabinetmaker and upholsterer William Vile and John Cobb (map point 16)occupying conjoined houses that were leased by Vile’s master, the cabinetmaker William Hallett, which had previously been the shop and house of the first-generation Huguenot goldsmith and “toyman” Thomas Harrache, who operated in St. Martin’s Lane from 1740 until 1751 when he departed for Pall Mall.[23] Multi-paned glass windows along the busy corner of St. Martin’s Lane and Long Acre would have been plum display space for the glittering luxury trades of goldsmithing and cabinetmaking. Roubiliac’s reasons for choosing the St. Martin’s Lane house may have been practical but were probably also social and professional. Not only did the Harrache family supply bronzes to Roubiliac, but Thomas Harrache also acted as his executor upon the sculptor’s death in 1762.[24]

These types of professional and social connections were formed by artists with shared cultural and artistic identities in an urban environment that was conducive to their expression. Taking this single block, which by the 1750s attracted two of the most eminent cabinetmaking and upholstery workshops of the mid-eighteenth century—Chippendale and Rannie, and Vile and Cobb, along with Roubiliac, Harrache, and the lesser-known Bell—suggests that creativity flourished in numbers. The reasons why anyone chose one house over another were probably myriad, yet even the mundane details of the location, space, and amenities offered by a built environment yield information about the nature of artistic production and collaboration.

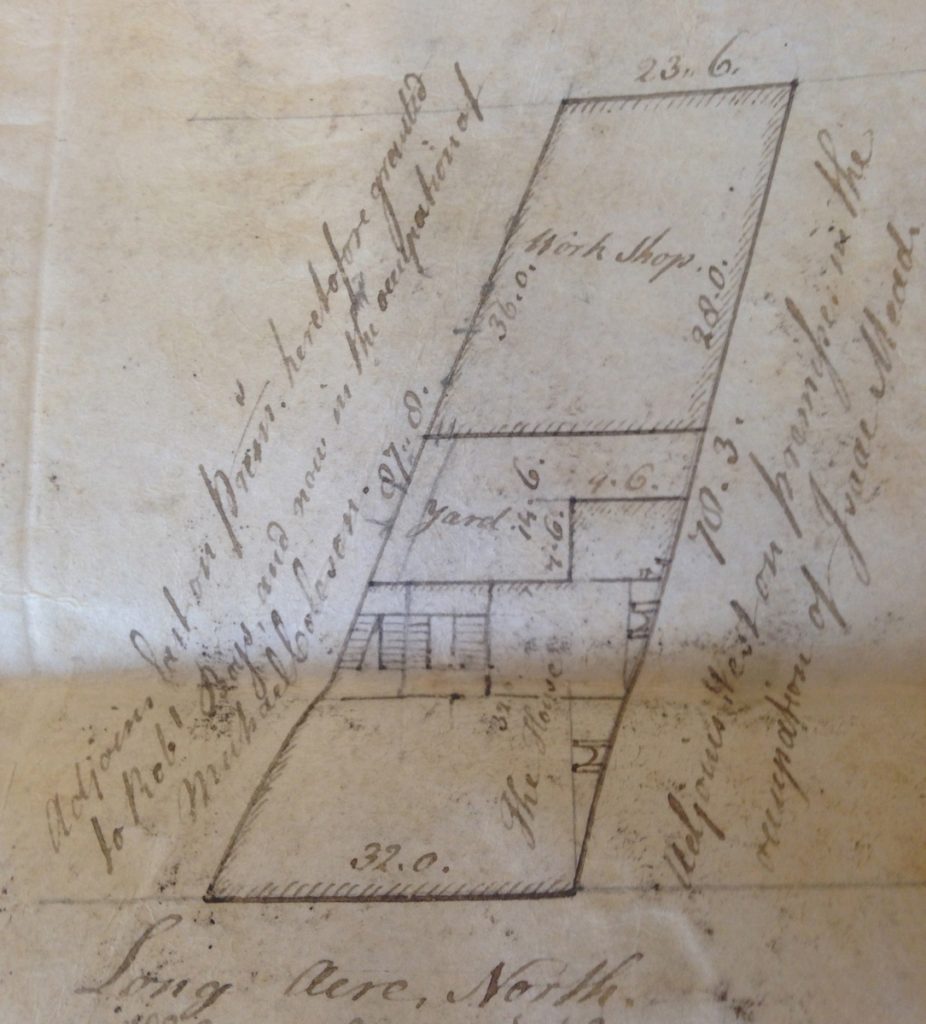

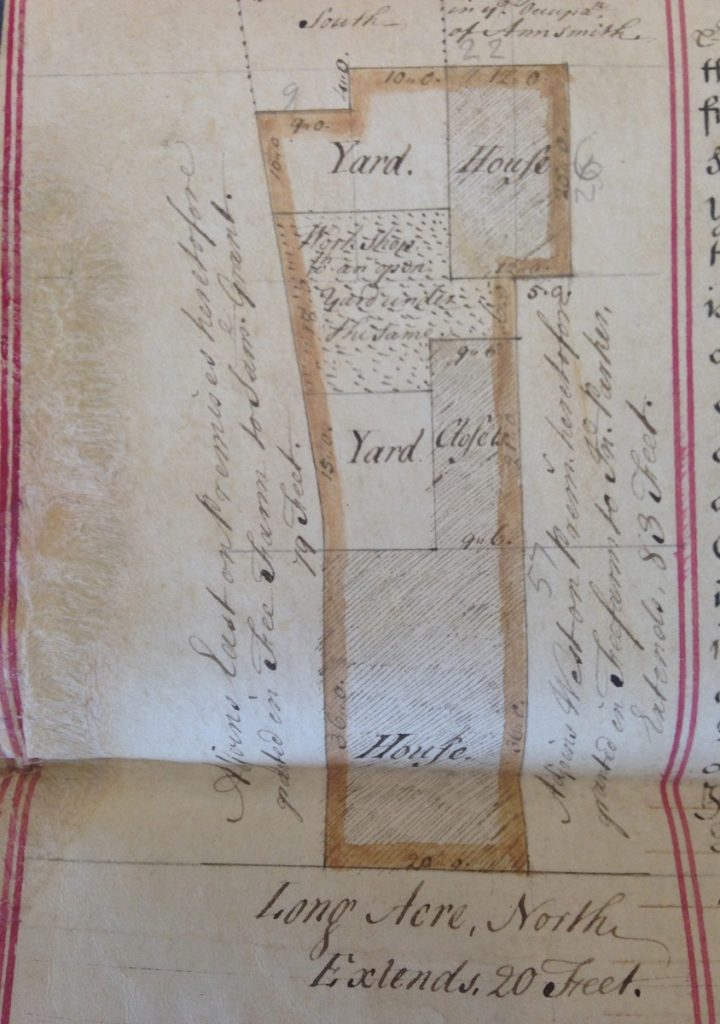

No significant eighteenth-century London furniture maker’s workshop survives today, but their floorplans were sometimes documented in estate leases. Around the corner from Hallett, Vile, and Cobb along the south side of Long Acre stood the house and workshop of the cabinetmakers William and John Linnell (map point 17). William Linnell’s 60-year lease includes a house plan showing a 32-foot frontage along Long Acre with a small yard and workshop building behind it (Fig. 5a).[25] The scale of the property and £20 annual rent are typical of the retail shops and residences of the street, and the basic floorplan is typical of the small London house of the eighteenth century.[26] It is somewhat larger than the property down the road of the carver and gilder James Pascall (map point 27), who carved the magnificent furniture in the gallery at Temple Newsam. Pascall’s property included a 20-foot frontage on Long Acre and a back area with storage, a workshop, and a second small building on two open yards (Fig. 5b).[27] With moderate space behind the house, the Linnells and Pascall appear to have had about the same workshop and retail space as other neighboring artisans in the furniture trade along the street.[28]

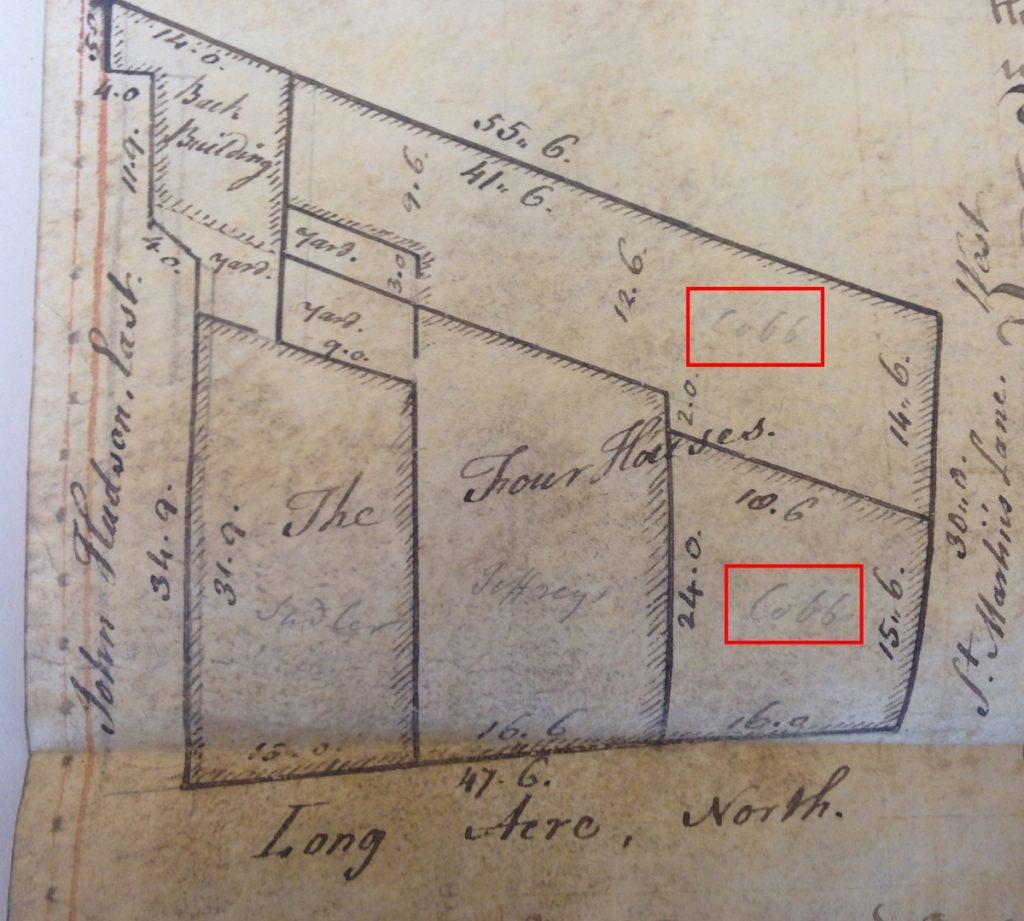

By the early 1750s, the cabinetmaker William Hallett and his business partner Robert Halliwell controlled five houses along the corner of Long Acre and St. Martin’s Lane, including Thomas Harrache’s former premises. Hallett leased two of the houses to his former apprentice William Vile and his partner John Cobb, whose name is written on the floorplan of the lease from the Duke of Bedford.[29] The other houses (two pictured on this plan and a third leased separately) were occupied, according to the lease, by a victualler and a cheesemonger, suggesting that Hallett and Halliwell found the houses more useful as rental income than as workshop space (Fig. 6). Of the houses occupied by Vile and Cobb, the floorplan shows that there were only small yards and a single back building on the property, but even these don’t seem to be accessible from the cabinetmaker’s houses. Instead, we see just two adjacent properties with combined frontages on St. Martin’s Lane of about 30 feet, with an additional frontage of almost 17 feet on Long Acre. This gave them considerable public-facing retail space but little workshop space.

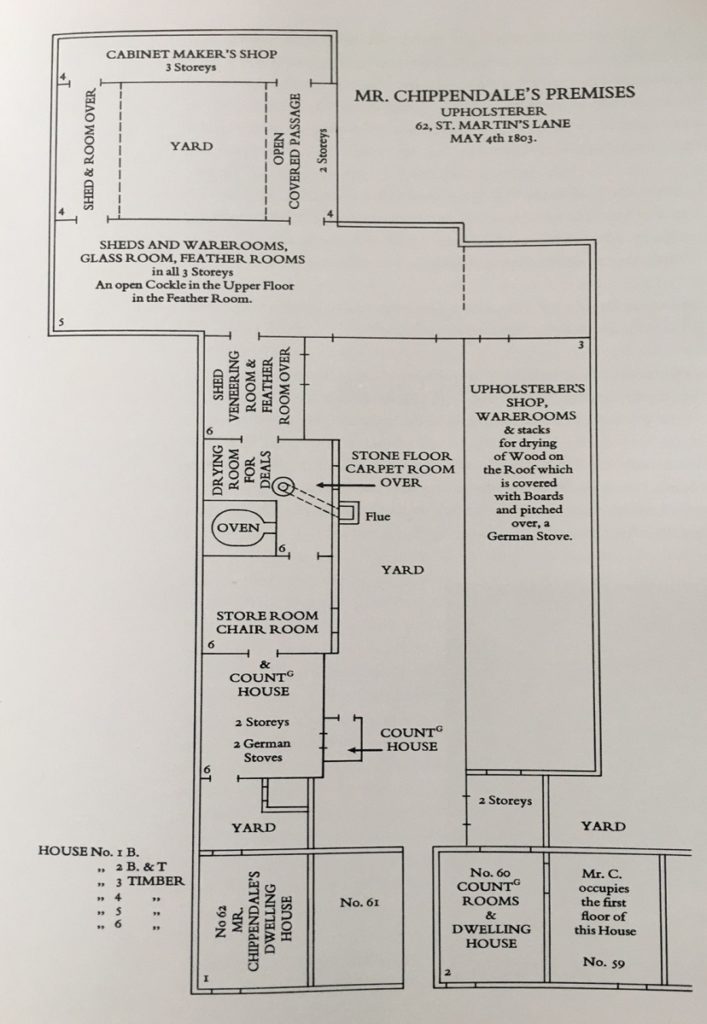

Compare this to the substantially different layout of their neighbor Thomas Chippendale’s property (Fig. 7). Though this plan is from 1803, it is accepted as also describing the general scale of the business that Chippendale and Rannie established in the 1750s. Three houses on St. Martin’s Lane flank a passageway that leads to extensive workshops and warerooms that housed almost all aspects of furniture making, from timber storage to upholstery. It shows what Pat Kirkham has termed the “comprehensive manufacturing workshop” that she argues emerged in this period.[30] Unlike Chippendale, Hallett, Vile and Cobb, and Goodison (and probably most of the other cabinetmakers in the street) were all operating from houses far too small to accommodate the multiple materials, skills, and stages of production of the very complex furniture attributed to them.

Consider, for instance, a splendid jewel cabinet supplied by William Vile to Queen Charlotte in 1762 (Fig. 8). The range of materials indicates a collaborative object that brought together the skills of at least one joiner to create the carcass, mahogany wood carvers and veneer specialists, ivory penwork, and a skilled cabinetmaker to assemble each of these specialist pieces. Vile’s bill indicates that the locks were supplied by Mrs. Elizabeth Gascoigne, whose signature is also found on furniture locks attributed to Chippendale.[31] The ivory penwork is more typical of southern German furniture of this period than English, suggesting the involvement of immigrant specialists. At the same time, the mahogany carving on and around the cabriole legs was a signature style of London carvers. Taking into account the complexity of each of these specialist skills and the range of styles present alongside the spatial layout of Vile and Cobb’s workshops makes clear that such a work could only be supplied through a network of subcontractors.[32] As Helen Clifford, building on the work of labor historians, has noted, “the assembly line ran through the street, where the material in its different stages of completion was carried from one manufacturer to another.”[33]

Although Vile may have been the cabinetmaker who assembled the final carved, inlaid, and veneered pieces and perhaps was its designer as well, the role of overseeing the entire process, including design, was often the domain of the upholder (or upholsterer). In 1747, Robert Campbell described the upholder as the “chief Agent” in furnishing a house, “the Man upon whose Judgment I rely in the proper Business of the Choice of Goods; and I suppose he has not only Judgment in the Materials, but Taste in the Fashions, and Skill in the Workmanship,” whereas he described the cabinetmaker as the upholder’s “right-hand Man … the most curious Workman in the wood way, except the Carver.”[34] While teams of upholders and cabinetmakers came to dominate the comprehensive manufacturing workshop that furniture historians acknowledge emerged in this period, the dense artistic neighborhood of St. Martin’s Lane facilitated another version of large-scale decorative production through networks of subcontracting.

In this way, upholding and cabinetmaking partnerships in St. Martin’s Lane operated similarly to the marchands merciers of Paris, who designed furniture and interiors by bringing together skilled specialists and supervising execution. The neighborhood itself, with its remarkable concentration of specialist trades, worked as an ad hoc comprehensive manufacturing firm in which cabinetmakers and upholsterers first attracted clients with smart frontage on a visible street. Then, they subcontracted work throughout the neighborhood, where pieces could be easily shuttled to the cabinetmaker and upholder’s shop from the workshops of joiners, turners, carvers, glaziers, and specialists in veneer, marquetry, ceramics, and brass, with no one trade taking on the capital of running a large manufacturing firm.

Painters, Printmakers, Framemakers, Neighbors

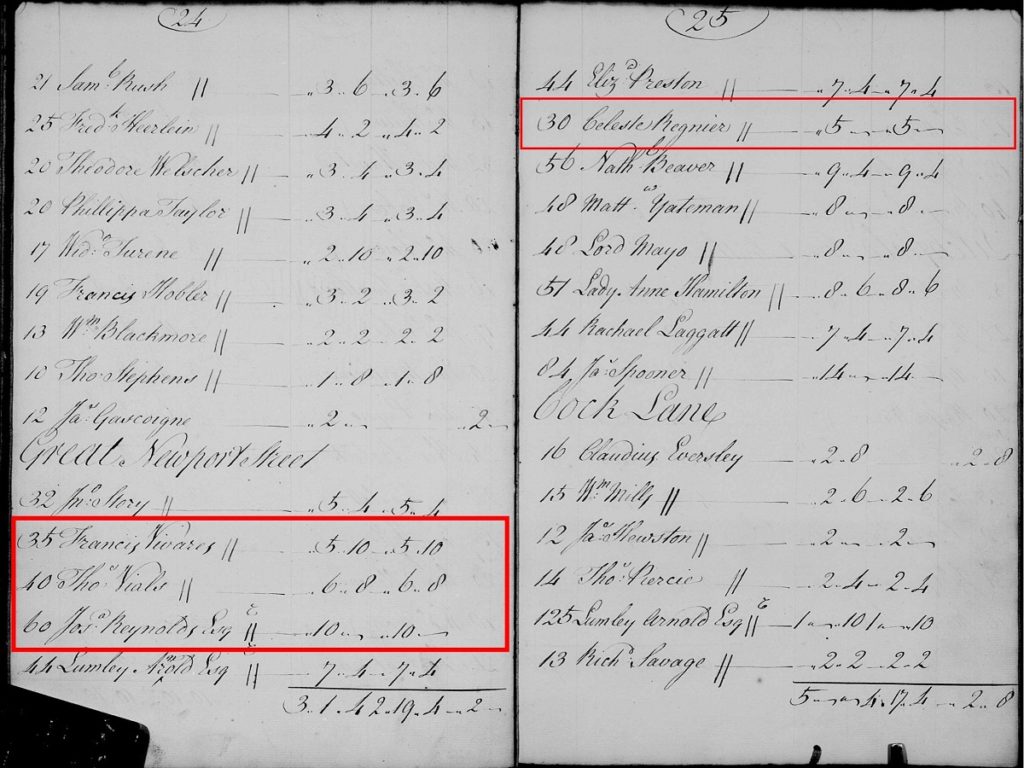

The notion of the neighborhood itself as a decentralized institution, with notable concentrations of artists and resources clustered together without a single institution binding them together, occurred in many other blocks around the neighborhood. By 1754, Joshua Reynolds had left his lodgings adjacent to the St. Martin’s Lane Academy in the house of the “man midwife” and surgeon Christopher Kelly in St. Martin’s Lane (map point 4) to establish his own house and studio around the corner on Great Newport Street (map point 5). His two immediate neighbors to the west were the printsellers Francis and Susanna Vivares (map point 28) and the carver Thomas Vialls (map point 29) (Fig. 9). From their Great Newport Street house, Francis and Susanna Vivares ran a printshop with an extensive stock that ranged from Old Master prints, contemporary French and English landscapes and ornament prints, and Francis’s own prints and furniture designs.[35] Thomas Vialls specialized in carved and gilded picture frames and was the framemaker of choice for George Stubbs and, not surprisingly, Joshua Reynolds.

Indeed, Vialls and Reynolds moved to Great Newport Street in the same year, along with Celeste Regnier (map point 30), the printseller and future wife of Louis François Roubiliac. Vialls, Reynolds, and Regnier each occupied houses that included studio or retail space in a set of five buildings that had been occupied until 1753 by the cabinetmaker William Hallett (map point 15). When Hallett moved out, the houses were freshly renovated by Lumley Arnold, a barrister whose family ran a cattle-dealing and coach business in Upper St. Martin’s Lane, including stables and seven dwelling houses in that block. William Hogarth painted Arnold’s father, George, and sister, Frances, in 1740.[36] Vialls followed Reynolds to Leicester Square by 1766 (map point 31), while the Vivareses and Regnier (by then, “Mrs. Roubiliac”) remained in Great Newport Street.

The observant reader of this page of the rate book will also notice the name of Francis Noble, the bookseller with the enormous shop sign in Sandby’s painting at the beginning of the essay (Fig. 1). These kinds of chance encounters in rate books make them an under-utilized source for archival serendipity and for filling in the social history of a neighborhood and an art world. They also provide another tool in the art historian’s kit for attribution and object history. While there is no rule that a painter or his patron should favor the framemaker next door—the decision probably depended more on the decorative context of a painting’s destination than the urban context of its making—it offers another potential piece to the puzzle of connoisseurship.

The numerous documented frames by Vialls surrounding Reynolds’ paintings all date from the 1760s and 70s, when both men were in Leicester Fields.[37] Could an acknowledgment of the proximity of painter and framemaker from 1754 until 1760 encourage us to look anew at the frames of the nearly 500 portraits painted in Reynolds’ Great Newport Street studio for a potential attribution to Vialls? Not only would that tell us something about Reynolds’ studio practice, but it also would offer, perhaps, the earliest known work of Vialls.

The close proximity of Reynolds and Vialls also brings in yet another character to the story. The carver and designer Thomas Johnson (map point 32) wrote in his autobiography that in 1756:

I was soon applied to by Mr. Thomas Vialls, a carver, in very great business, to make all his drawings, and do the principal part of his work; for whom I afterwards did business, to the amount 150l. [£150] per year, for more than twenty-one years. I had taken a small house in Queen-street, near the Seven Dials, which soon proving too little, I moved to Grafton-street, St. Ann’s, Soho, where with Mr. Whittle’s and Mr. Viall’s work, &c. I had business enough for myself, four apprentices, and twenty-five journeymen…” [38]

Johnson’s Grafton Street workshop, large enough to coordinate the work, if not actually accommodate the workbenches, of 25 journeymen was one block from Vialls’ Great Newport Street house.[39] His description reveals the extensive use of subcontracting in the furniture trades and highlights the importance of geographic proximity in that process.

The art worlds of Thomas Johnson and Joshua Reynolds may seem miles apart, but in fact, the men were only a block apart, and they shared a professional connection through Vialls. This cluster, along with that of Roubiliac, Harrache, Chippendale, Hallett, and Vile and Cobb, provides snapshots of an art world horizontally integrated by the street and offers an alternative model to the vertical hierarchies of “fine” and “decorative” arts upon which art historians have traditionally operated. Like the ungoverned rococo style that flourished around this serpentine-shaped street, the art world of St. Martin’s Lane was defined by its array of practitioners of skilled, collaborative, and dynamic media.

Stacey Sloboda is the Paul H. Tucker Professor of Art History at the University of Massachusetts, Boston

[1] I’m grateful to Jonny Yarker, who discussed this image with me and pointed out the cherub. Comparing the image with rate book information on Noble’s house and John Rocque’s map suggests that the view was taken from a house on Castle Street looking east toward the north side of St. Martin’s Court. The painting was in a private collection until 2019 and exhibited in 1994 at the Leger Galleries. See Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker Ltd – Recent Acquisitions 2019/20 for a catalogue entry.

[2] Mark Girouard, “The Two Worlds of St. Martin’s Lane,” Country Life (3 February 1966), 224-27.

[3] Ilaria Bignamini, “George Vertue, Art Historian, and Art Institutions in London, 1689-1768: A Study of Clubs and Academies,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 54 (1988), 1-148; Martin Postle, “St. Martin’s Lane Academy: True and False Records,” Apollo (July 1991), 33-38; Vic Gatrell, The First Bohemians: Life and Art in London’s Golden Age (London: Penguin, 2014).

[4] Girouard, “The Two Worlds of St. Martin’s Lane,” 225.

[5] Notable exceptions are: Hugh Phillips, Mid-Georgian London (London: Collins, 1964);Desmond FitzGerald, “Chippendale’s Place in the English Rococo,” Furniture History 4 (1968), 1-9; Anne Puetz, “Drawing from Fancy: The Intersection of Art and Design in Mid-Eighteenth-Century London,” RIHA Journal (2014), https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/rihajournal/article/view/69968; and Femke Speelberg, “Dissecting the Director: New Insights about its Production and Chippendale as a Draughtsman,” Furniture History 54 (2018), 27–42.

[6] This article is derived from my in-progress book manuscript on the eighteenth-century artists and artisans around St. Martin’s Lane. On the neighborhood as a category of historical analysis, see Jeremy Boulton, Neighborhood and Society: A London Suburb in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987); Nicholas A. Eckstein, The District of the Green Dragon: Neighborhood Life and Social Change in Renaissance Florence (Florence: Olschki, 1995); David Garrioch, Neighborhood and Community in Paris, 1740-1790 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); and Linda Stone-Ferrier, The Little Street: the Neighborhood in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art and Culture (London: Yale University Press, 2022).

[7] Barney Warf and Santa Arias, The Spatial Turn: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 2009), 3.

[8] Though some London painters, sculptors, and wood workers still joined guilds and even sometimes registered apprentices through them, with the exception of gold and silversmiths (whose work had to be assayed), guilds held little importance for the artistic and luxury trades of St. Martin’s Lane, which technically speaking is in the city of Westminster, outside the regulatory reach of the City of London companies. See Michael Berlin, “Broken All in Pieces: Artisans and the Regulation of Workmanship in Early Modern London,” in The Artisan and the European Town, 1500–1900, ed. Geoffrey Crossick (Aldershot, UK: Scolar Press, 1997), 75-91. On artisanal clustering, see Claartje Rasterhoff, “The Spatial Side of Innovation: The Local Organization of Cultural Production in the Dutch Republic, 1580-1800,” in Innovation and Creativity in Late Medieval and Early Modern European Cities, ed. Karel Davids and Bert De Munck, (Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2014), 161-188. For an account of dispersal, rather than clustering, of artisanal trades in Paris, see Natacha Coquery, “The Aristocratic Hôtel and its Artisans in Eighteenth-Century Paris: The Market Ruled by Court Society,” in Geoffrey Crossick, ed., The Artisan and the European Town, 92-115.

[9] The commercialization of culture in eighteenth-century Britain has a large bibliography. Key sources include J.H. Plumb et al., The Birth of a Consumer Society (London: Europa, 1982); John Brewer, The Pleasures of the Imagination (London: Harper Collins, 1997); David Solkin, Painting for Money (London: Yale University Press, 1993). Of particular relevance here is Peter Borsay, “Invention, Innovation, and the ‘Creative Milieu’ in Urban Britain: The Long Eighteenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Cultural Economy,” in Creative Urban Milieus: Historical Perspectives on Culture, Economy, and the City, ed. Martina Hessler and Clemens Zimmermann (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2008), 77–100; and John Styles, “Product Innovation in Early Modern London,” Past and Present 168 (August 2000), 124-169.

[10] The center of the London book trade was further to the east around St. Paul’s Churchyard, Paternoster Row, Fleet Street, and Cornhill. See James Raven, Bookscape: Geographies of Printing and Publishing in London before 1800 (London: British Library, 2014).

[11] Charles Saumarez Smith acknowledges the role of geography in the early development of the Royal Academy in The Company of Artists: The Origins of the Royal Academy of Arts in London (London: Modern Art Press, 2012), as does Rosie Dias, “A World of Pictures: Pall Mall and the Topography of Display,” in Georgian Geographies: Essays on Space, Place, and Landscape in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Miles Ogborn and Charles W.J. Withers (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2044), 92–113. See also Matthew Hargraves, Candidates for Fame: The Society of Artists of Great Britain 1760–1791 (London: Yale University Press, 2005). Martin Myrone’s Making the Modern Artist: Culture, Class and Art-Educational Opportunity in Romantic Britain (London: Yale University Press, 2020) reveals the significant disconnect between the Academy’s academic rhetoric and its practices.

[12] The notion of greater London as a conglomeration of distinct neighborhoods has been operative since at least the eighteenth century and was noted as its defining feature by Steen Eiler Rasmussen, London: The Unique City [1934] (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1964). See also Hugh Phillips, Mid-Georgian London; and Elizabeth McKellar, Landscapes of London: The City, the Country, and the Suburbs, 1660–1840 (London: Yale University Press, 2014).

[13] Elizabeth Einberg, “Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of George Lambert,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 63 (2001), 131–35.

[14] For other studies of collaboration amongst artists around the neighborhood, see Rosie Razzall, “Paul Sandby Copying Gainsborough: Sharing, Sociability, and Self-fashioning,” Master Drawings 58:2 (Summer 2020), 226–46; David Pullins, “Stubbs, Vernet & Boucher Share a Canvas: Workshops, Authorship & the Status of Painting,” Journal18, issue 1 Multilayered (Spring 2016), https://www.journal18.org/334; Malcolm Baker, “The Making of Portrait Busts in the Mid-Eighteenth Century: Roubiliac, Scheemakers and Trinity College, Dublin,” The Burlington Magazine 137:1113 (December 1995), 821–31; and Malcolm Baker, “Roubiliac’s Argyll Monument and the Interpretation of Eighteenth-Century Sculptors’ Designs,” The Burlington Magazine 134:1077 (December 1992), 785-97.

[15] Some of the same methodological challenges are described by Hannah Williams in her description of mapping the eighteenth-century Parisian art world. Hannah Williams, “Artist’s Studios in Paris: Digitally Mapping the Eighteenth-Century Art World,” Journal 18, Issue 5 Coordinates (Spring 2018), https://www.journal18.org/issue5_williams/. Articles in the journal ARTL@S provide a range of methodological approaches to mapping and art worlds. See particularly, vol. 2, issue 2 “Do Maps Lie?,” https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas/vol2/iss2/

[16] The records for most Westminster parishes, including St. Martin-in-the-Fields, St. Ann, and St. Paul (the three parishes related to the neighborhood in and around St. Martin’s Lane), are preserved at the Westminster City Archives, and have been indexed by FindMyPast.org. Digital scans of some of the microfilm copies of the rate books can be accessed on FamilySearch.org. The rate books are a familiar source for genealogists as well as urban historians such as Hugh Philipps, whose Mid-Georgian London is oftentimes an illustrated and narrated version of the rate books, and a standard source for the multi-volume Survey of London, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/search/series/survey-london. Furniture historians have likewise made good use of parish rate books, primarily to trace business history, such as Tessa Murdoch, Europe Divided: Huguenot Refugee Art and Culture (London: V&A Publishing, 2021). Nicholas Eckstein discusses the methodological importance of similar, though more detailed, Florentine tax documents in “Prepositional City: Spatial Practice and Micro-Neighborhood in Renaissance Florence,” Renaissance Quarterly 71:4 (2018), 1235-71.

[17] The main limitation of the rate books is that not everyone paid parish rates. Generally, only leaseholders (that is, those who held a long-term lease from the estate that owned the property) were rate payers. Shorter-term tenants and lodgers sometimes appear in the rate books if they were the primary occupant of a house or part of a house, but not consistently. Thus, younger artists, as well as artists from elsewhere in Britain and Europe who came temporarily to London, rarely appear in rate books. Additionally, multiple occupants of a single house sometimes appear as separate entries, making it difficult to say how many houses were in a street, or who lived in the same house or as neighbors. Likewise, entries almost always refer only to the head of household, so they tell us nothing about the other family members, apprentices, lodgers, and household staff who lived there. Men are more likely to be listed as rate payers, but a surprising number of single and widowed women, and occasionally married women, also appear. Finally, rates were generally only assessed on occupied residential properties, so institutions like the St. Martin’s Lane Academy do not appear in the rate books, or, if the property is listed, no personal name of a rate payer is typically indicated.

[18] Christopher Gilbert, The Works of Thomas Chippendale, 2 vols. (New York: MacMillan, 1978); Morrison Heckscher, Chippendale’s Director: A Manifesto of Furniture Design (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018); and the essays in the 2018 issue of Furniture History.

[19] Qtd. In Geoffrey Beard and Christopher Gilbert, eds., “Bell, Daniel,” in Dictionary of English Furniture Makers 1660-1840, (Leeds: Furniture History Society 1986), https://bifmo.history.ac.uk/entry/bell-daniel-1724-34.

[20] Roubiliac’s premises were smaller, however, than those of his main rivals (and sometimes collaborators) Peter Scheemakers in Vine Street and Henry Cheere in Old Palace Yard, both occupying residences in the less densely populated western edges of Westminster. Tessa Murdoch, “The Business Practice of Louis François Roubiliac, 1752-62,” The Sculpture Journal 30:3 (2021), 208.

[21] Pictorial signs related to a shop’s trade, such as this one, decreased with the piecemeal adoption of street numbers in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Hogarth carved a cork “Van Dyck’s Head” that hung outside his house and print shop in Leicester Square, and Chippendale advertised from the “Sign of the Chair,” suggesting that he hung an actual chair outside his shop.

[22] James Paine’s “Design for a Cabinet Warehouse” displays a dramatic bow-fronted window display space. Since Paine was a subscriber to Chippendale’s Director, and the two men shared Yorkshire origins and lived almost immediately across the street from one another, it has been suggested that it was a design for Chippendale’s shop. Fitz-Gerald, “Chippendale’s Place,” 3.

[23] Many of the elite goldsmiths of the period, including Paul de Lamerie, George Wickes, Paul Crespin, and Nicholas Sprimont, gathered nearby in the streets just west of Leicester Fields.

[24] Malcolm Baker, “Rococo Styles in Eighteenth-Century English Sculpture,” in Michael Snodin, ed., Rococo: Art and Design in Hogarth’s England (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1984), 280. Tessa Murdoch’s study of Roubiliac’s bank accounts show that he paid made three payments to Thomas Chippendale in 1756-59, possibly for the mahogany shipping cases he sometimes used for sculptures, or possible for furniture for his own house. Murdoch, “Business Practice,” 293.

[25] “Duke of Bedford to William Linnell, Counterpart Lease,” 1749, Bedford Estate Records, London Metropolitan Archives (hereafter, “LMA”), E/BER/CG/L/104 no. 10. When the Linnells moved to their much larger premises in Berkeley Square in 1754, Linnell sublet the Long Acre house to the engraver and print publisher Matthais Darly. LMA, E/BER/CG/03/002/B.

[26] Peter Guillery, The Small House in Eighteenth-Century London: A Social and Architectural History (London: Yale University Press, 2004). The plans seen here correspond closely with the variety of one- and two-room floor plans illustrated on page 42. Guillery observes that the rear-staircase “achieved universal acceptance in London’s speculative housing after 1720,” 61.

[27] “Duke of Bedford to James Pascall, Counterpart Lease,” 1744. LMA, E/BER/CG/L/104 no. 8.

[28] The 1755 plan and estate survey of the Mercer’s Company Estate (Mercer’s Company Archive) indicates the houses of ten cabinetmakers and one upholsterer along the north side of Long Acre, each with premises equivalent to Linnell and Pascall’s on the south side of the street, on the Bedford Estate.

[29] “Duke of Bedford to Robert Halliwell, Counterpart Lease,” 1748. LMA, E/BER/CG/L/104 no. 15. Halliwell seems to have been a financial partner of Hallett’s.

[30] Pat Kirkham, The London Furniture Trade, 1700–1870 (Leeds: Furniture History Society, 1988), 57.

[31] “William Vile, Jewel Cabinet,” Royal Collections Trust online collections, https://www.rct.uk/collection/35487/jewel-cabinet. On Gasciogne’s work for Chippendale, see “A George III Mahogany Twin-Pedestal Desk, Attributed to Thomas Chippendale,” Lot 40 in Christie’s “Mt. Congreve: The London Sale,” (23 May 2012), https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5561148.

[32] Recent studies of the London furniture trade highlight the importance of subcontracting. See Adam Bowett, Early Georgian Furniture, 1715–1740 (Woodbridge: Antique Collector’s Club, 2009); and Laurie A. Lindey, “The London Furniture Trade, 1640–1720,” Ph.D. Dissertation (University of London, 2016), which builds upon the earlier work of Edward Joy, “Some Aspects of the London Furniture Industry in the 18th Century,” unpublished M.A. dissertation (University of London, 1955); and Kirkham’s London Furniture Trade. For a discussion of the historiography of subcontracting in eighteenth-century luxury trades, see Helen Clifford, “Making Luxuries: The Image and Reality of Luxury Workshops in 18th-Century London,” in The Vernacular Workshop: From Craft to Industry, 1400-1900, ed. P.S. Barnwell, Marilyn Palmer, and Malcolm Airs (York: Council for British Archaeology, 2004), 17-27.

[33] Clifford, “Making Luxuries,” 19.

[34] Robert Campbell, The London Tradesman, (London, 1747), 169-70.

[35] The range of stock can be gleaned from two auctions organized by Susanna Vivares after Francis’s death. A Catalogue of the all the Remaining Part of the large and Valuable Stock of Prints and Books of Prints of Mr. Francis Vivares (25 October 1781); and A Catalogue of About One Hundred and Ten Fine Drawings, the Work and Property of Mr. Thomas Vivares (2 January 1789). (National Art Library II.RC.Q.25)

[36] The five houses adjacent to the Vivareses are listed in the rate books as empty in 1753, with rates paid by Lumley Arnold, whereas all five are listed as occupied the following year, suggesting that Arnold renovated the houses as a block. On the Arnold family’s property, see “Upper St. Martin’s Lane and Cranbourn Street Area: Salisbury Estate,” in Survey of London: Volumes 33 and 34, St Anne Soho, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols33-4/pp339-359. Frances Arnold and George Arnold’s 1738–40 portraits by Hogarth are now at the Fitzwilliam Museum. Lumley’s own rather indifferent 1766 portrait retains its original splendidly carved rococo frame. Elizabeth Einberg, William Hogarth: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings (London: Yale University Press, 2016), cat. 138 and 160.

[37] The “Reynolds Room” at Knole might also be fairly described as the “Vialls Room,” as most of Reynolds’ work there, including John Frederick Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset (1769)and Wang-I-Tong (c. 1776), retain their original Vialls frames. Jacob Simon, “ A Guide to the Picture Frames at Knole, Kent,” (1998, revised 2013), https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/programmes/the-art-of-the-picture-frame/guides-knole.php; and “Vialls, Thomas,” in Jacob Simon’s indispensable online database, “British Picture Framemakers, 1600-1950,” https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/programmes/conservation/directory-of-british-framemakers/v. On Reynolds’ magnificent house-studio in Leicester Square, see Donato Esposito, “Artist in Residence: Joshua Reynolds at No 47, Leicester Fields,” in The Georgian Town House: Building, Collecting, and Display, ed. Susanna Avery-Quash and Kate Retford (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), 191-210.

[38] Thomas Johnson, Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author, ed. J. Simon (London: Furniture History Society, 2003), 51.

[39] Though Johnson’s name doesn’t appear in the ratebooks for Grafton Street, it seems likely that his house was the one previously occupied by the carver Henry Jouret, whom we know partly from his tradecard (British Museum, Heal 96.7) designed by Mattias Lock. Jouret left Grafton Street in 1755 when he moved to Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, which may have provided a ready carving studio for Johnson.

Cite this article as: Stacey Sloboda, “St. Martin’s Lane: Neighborhood as Art World”, Journal18, Issue 15 Cities (Spring 2023), https://www.journal18.org/6712.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.