Alicia Caticha

Among the many enduring myths surrounding Marie Antoinette is the bucolic fantasy of the extravagant queen dressing up as a milkmaid at her Hameau, a model village and farm on the grounds of the Château de Versailles. Central to this fiction was Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s scandalous 1783 portrait of Marie Antoinette wearing a loose white cotton dress akin to a chemise, or petticoat (Fig. 1). Deemed inappropriate for someone of the queen’s station, the portrait was quickly removed from the Salon walls. However, the damage was already done. Of the many names these dresses would take on in the decades that followed, the epithet chemise à la reine permanently linked white cotton to Marie Antoinette and her notorious—if exaggerated—penchant for playing peasant. Although in reality the Hameau (and its relaxed dress code) acted as a refuge to host intimate gatherings and escape the rigorous etiquette of the French court, film montages such as the one featured in Sofia Coppola’s 2006 Marie Antoinette (Fig. 2) have only further inscribed this fantasy into our collective understanding of the infamous queen.

Unexpected, however, was how this myth would capture the imagination of students when I proposed the course “Fashion, Race, and Power,” taught online at Northwestern University during the spring of 2021.[1] Inspired by new digital resources such as the Fashion and Race Database and Doctor Jonathan Square’s zine and Instagram, Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom, my students and I interrogated the history of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French fashion through the lens of European colonialism.[2] Revisiting Paris’s role and identity as the “fashion capital of the world,” it became clear that the success of the Parisian fashion industry relied heavily on France’s active participation in the Atlantic slave trade and a host of other exploitative global networks.

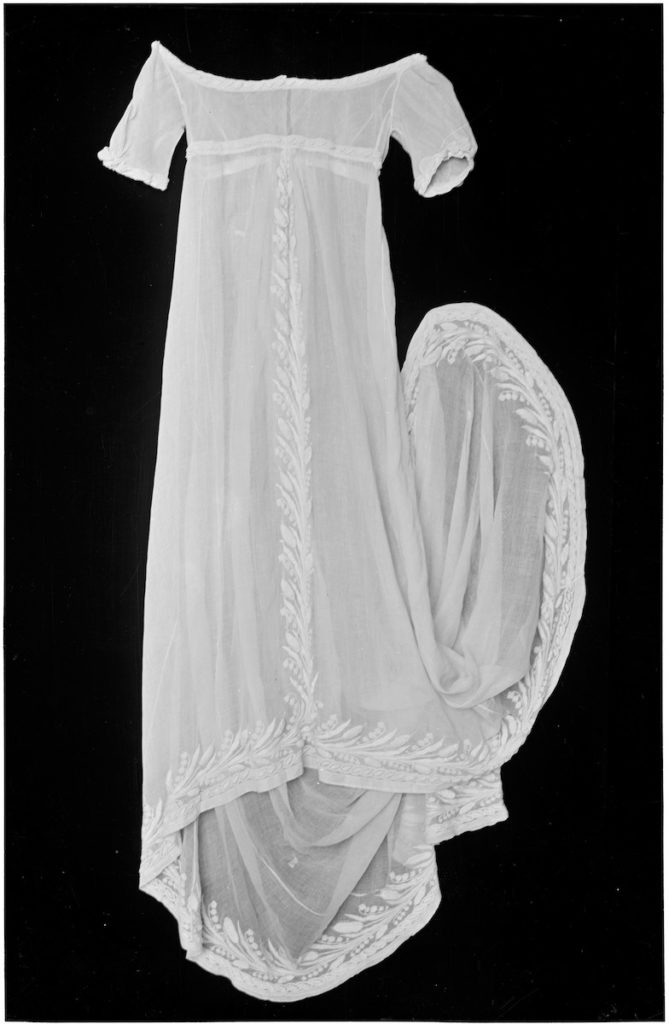

In a bid to engage the digital in the online classroom, students were asked to turn to the fashion journalist Elizabeth Holmes’s Instagram on the political valences of the modern British royal family’s sartorial choices.[3] Students wrote “pictorial essays” in the vein of Holmes’s impeccably annotated Instagram stories, in which they analyzed a piece of clothing or visual culture to creative—and revelatory— results. As we traced the development of a new fashion system in eighteenth-century France—spurred by the nascent figure of the marchand de mode, the emerging fashion press, and a global textile trade connecting India to Saint-Domingue to Paris, among other locales—the cotton chemise à la reine and related empire style dress (Fig. 3) became recurring themes across student work.

At the very historical moment the global fashion market emerged, the French Atlantic colonial empire had reached its political and economic apex. The plantation systems of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), Martinique, and Guadeloupe fueled the French economy via the production of sugar, tobacco, and cotton by an enslaved African workforce.[4] Cotton was particularly novel in terms of both its materiality and its status as a commodity.[5] Lightweight and breathable, the textile transformed how people dressed on both sides of the Atlantic. At the same time, it was quite literally currency to be used in the fiscal exchange for enslaved men and women in West Africa. The empire style dress, although only popular for a brief time at the turn of the nineteenth century (ca. 1790-1812), perfectly embodied the global economic and social forces at play in the Atlantic world. My students became collectively obsessed with unpacking the layers of meaning implicit within this one historical trend—long after we had moved on to later fashions and periods. (At one point, my teaching assistant and I, uncertain why this subject had captured the class imagination, even debated whether to forbid them from writing on the subject in future essays!) As would become abundantly clear as the course continued, this brief period of fashion history resonated with the daily sartorial concerns of the “TikTok generation.”

Fixated on the historical narratives surrounding this white empire style dress, students rehashed every aspect surrounding its history, a narrative outlined—to the delight of this group of undergraduates—by Amelia Rauser in The Age of Undress.[6] Beginning with the familiar narrative of Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s controversial portrait of Marie Antoinette from the Salon of 1783, student essays pointed to her marchand de mode Rose Bertin’s appropriation of the white chemise silhouette from Creole women in the French Antilles. Looking to paintings and prints by Agostino Brunias (Fig. 4), other papers focused on the politics of textiles in the French Antilles, including how these cotton gowns were originally designed to accommodate the harsh realities of life in the enslaved societies of the Caribbean, from limited financial resources to simply surviving the blazing heat of the sun.

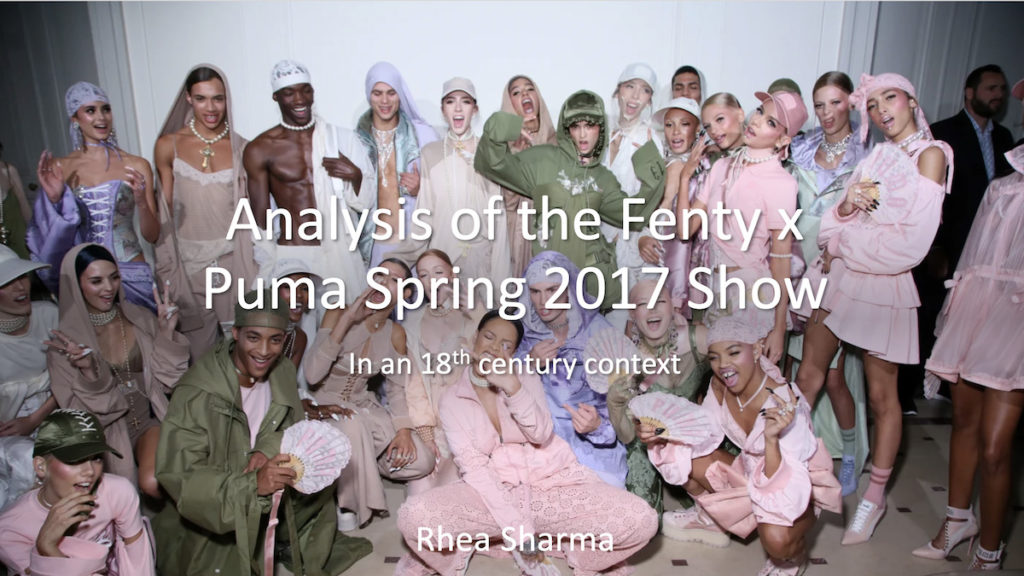

As discussions surrounding the chemise à la reine gave way to the robe à la grecque, the “sheer” notion that women sought to imitate living statues after the antique by adorning themselves in these thin gossamer empire style dresses only fueled the fire. The connections between cotton, the colonial world, and the racialization of whiteness and marble both echoed and foreshadowed the exploitation inherent to the fast fashion industry of the twenty-first century. The appropriation of headwraps (and even gold hoop earrings) by notable eighteenth-century “fashion icons” such as Juliette Récamier and Josephine Bonaparte introduced discussions surrounding cultural appropriation and the reclamation of the headwrap as durag two hundred years later. One student conceived of this history through an analysis of the celebrity drag queen Symone’s deployment of an eighteenth-century-inspired ten-foot-long durag on Season 13 of RuPaul’s Drag Race.[7] In fact, the exponential number of relevant contemporary comparisons introduced throughout their pictorial essays—from the opening musical number of Disney’s Hercules to Fenty’s 2017 collaboration with Puma (Fig. 5)—clearly underscored the cyclical nature of fashion and the ongoing importance of the eighteenth-century fashion system in our daily lives.[8]

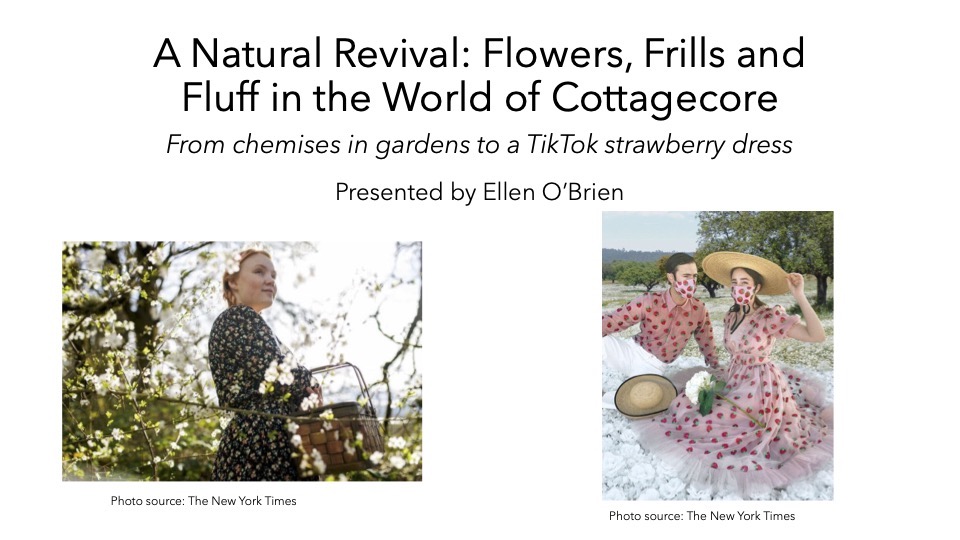

While I had structured “Fashion, Race, and Power” to encourage these lines of inquiry, sustained student interest in the empire style dress felt worthy of interrogation in its own right. Perhaps the narrative of the chemise à la reine had upended contemporary understandings of Marie Antoinette, who still looms impossibly large in the cultural consciousness. Maybe this was all a mere coincidence; did my students simply have Netflix’s newly released Bridgerton (2020) on the brain? After all, we had read and discussed Marlene L. Daut’s article, “Why did Bridgerton Erase Haiti?”[9] Turning again to the pictorial essays for possible explanations, themes of cultural appropriation, luxury, and leisure featured throughout—and all pointed, whether explicitly or obliquely, to a uniquely generational online phenomenon that had emerged on TikTok during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic: Cottagecore (Fig. 6).

Like many, I first learned of Cottagecore in the spring of 2020 due to Hill House’s infamously-named “Nap Dress.”[10] In the months that followed, the phenomenon seemed to be everywhere. The New York Times’s Isabel Slone wrote a feature on Liriki Matoshi’s strawberry midi dress (see Fig. 6, image on right) that had gone viral on TikTok: “With its pastel pink tulle overlay, plunging neckline, and gently puffed sleeves, it looks like something Marie Antoinette would wear if she were a modern day influencer.”[11] While the pink and white frothy aesthetic beckons twenty-first-century fantasies of Marie Antoinette, Cottagecore’s connection to the mythology of the French queen extends beyond these popular chemise dresses to a pseudo-historical social media performance of a pastoral lifestyle, primarily on TikTok. Scrolling through the images and accounts tagged #cottagecore, one finds influencers and everyday social media users wearing flouncy white empire-waist chemise dresses frolicking in fields of wildflowers, baking cookies, and even writing calligraphy by candlelight. Surely the art historian cannot help but understand this hyperfeminine version of Henry David Thoreau’s “return to nature” as akin to Marie Antoinette’s escape from the rigorous etiquette of court to the Hameau de la Reine.[12] Never mind that, as Meredith Martin has illustrated, Marie Antoinette’s pleasure dairy was part of a much longer history of aristocratic women deploying pastoral architecture as a means of establishing political power, benefiting from the experimental health benefits of milk, and reinforcing the connection between nature and the maternal body.[13]

Nevertheless, in 2020, the image of Marie Antoinette and the easy escape to nature afforded by her status is perhaps the perfect metaphor for the Cottagecore phenomenon: a return to nature without sacrificing the ease and privilege of “modern life.” The trend’s reach quickly extended beyond the realm of social media, particularly in the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic.[14] The popular video game Animal Crossing introduced new features in which players could make custom Cottagecore-themed islands for their characters. Taylor Swift released a surprise quarantine album, Folklore (2020), characterized by a “return to basics,” i.e. paired down songwriting. Capitalism wasn’t far from Swift’s mind, however; the vinyl album was released with a matching cozy sweater inspired by the album’s single “Cardigan.” Indeed, Martin’s descriptions of eighteenth-century fantasies of country living, facilitated by pastoral architecture, could very well double as a contemporary description of the ethos behind Cottagecore and its many valences: “Most [pleasure dairies] were in or near Paris, or otherwise in close proximity to the court. This enabled elite dairy owners to take up la vie champêtre without having to truly abandon city life, or, for that matter, their professional and social obligations.”[15] This nostalgic return to “simpler times” served—and continues to serve—as a refuge from the realities of living through one of the greatest public health crises of the past century, while remaining within both the comforts and constraints of contemporary society.

Critics of Cottagecore have rightfully pointed to the ways the aesthetic both romanticizes and whitewashes the realities of settler colonialism and the Antebellum south, renaming it “slavery cosplay” and “plantation-core.”[16] However, these satirical terms don’t register the growing number of Cottagecore practitioners of color actively engaged in deconstructing the presumed whiteness of rural spaces. To my surprise, the majority of Cottagecore’s critics are, in fact, its biggest fans. By pointing out the historical discrepancies between the romanticization of the pastoral present and past, Black Cottagecore influencers have created online spaces where this aesthetic can exist in tandem with dark historical truths. In the case of @enchanted_noir, a Black farm owner, the colonial and racial implications of Cottagecore are embedded throughout her feed. In TikToks detailing the history of Black farm ownership (Fig. 7), @enchanted_noir refutes criticisms that her participation in the aesthetic is a betrayal of her history and identity. Rather, she understands her engagement with nature as a reclamation of her ancestors’ lost land and an escape from the continued systemic injustices of the Atlantic slave trade and settler colonialism. In this vein, her TikTok grid alternates between ethereal photoshoots featuring handsewn contemporary versions of chemise and empire style dresses (Fig. 8) and practical advice for Black people looking to relocate to rural areas (Fig. 9). In many ways, Cottagecore has allowed people of color to reclaim nature at a moment when we as a society are only beginning to acknowledge the racism embedded in outdoor leisure activities, even in places such as New York City (recall the story of Christian Cooper, a Black birder in Central Park).[17]

What has become newly apparent to me, looking back on the student essays written on empire style dresses, are the prescient sartorial concerns with which my students entered the classroom. Unbeknownst to me was that the study of fashion would provide a group of Covid-19 undergraduates with extensive historical antecedents to pressing issues in their twenty-first-century daily lives. The historical narratives undergirding the empire style dress became inseparable from their own sartorial choices. Not only did they see themselves as performing the same ritualized escape to nature as Marie Antoinette two hundred years prior, but the history of Europe’s cultural appropriation of clothing fashioned by Black Caribbean women also echoed the internal debate regarding race, nature, and fashion taking place within the Cottagecore subculture.

The deeply embodied relationship we have to our clothing and bodily adornments is often erased in the academic study of fashion. But for many of my students, as they learned about the racialized history and exploitation present in eighteenth-century fashion, the long history of settler colonialism was no longer part of an abstracted past, nor a pedantic historical event only to be engaged within the classroom. Rather, by donning a viral strawberry dress or an over-the-shoulder “peasant top,” by following a specific TikTok account, or by liking an Instagram post, they were inscribing these histories onto their bodies, both physically and virtually.

I note the virtual impact of this embodied history of fashion precisely because the online footprint of many students shifted over the course of our time together. Quite literally, their TikTok algorithms began to include clips on the very histories under discussion in “Fashion, Race, and Power.” Each week students brought in TikTok after TikTok featuring twenty-somethings undertaking archival-based research on the history of fashion and applying (intentionally or otherwise) post-colonial and critical race theories to the subjects at hand.[18] In the current political landscape of the 2020s, these TikToks serve as a reminder that a generation of critical thinkers exists. Whether they are inside or outside of the academy, they are performing critical work on the history of eighteenth-century fashion and race that we should look to, both to inform and inspire our own research and teaching.

Alicia Caticha is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History at Northwestern University, IL

[1] I would like to thank Ariana Ray for her work as the graduate assistant to the Spring 2021 course “Fashion, Race, and Power.” Without her assistance and wisdom, teaching a new course online during the pandemic would have simply been impossible. I am immensely grateful to the editors of this issue, Susannah Blair and Stephanie O’Rourke for their thoughtful comments on this essay and for providing me with the space to explore TikTok and Cottagecore. I would also like to acknowledge S. Hollis Clayson for generously supplying me innumerable resources on French fashion; and Miriam Said and Michelle Smiley for insights into Cottagecore, nap dresses, and for reading early versions of this text. Above all, I would like to thank my students, who made teaching on Zoom a rewarding, intellectual, and thrilling endeavor. All online links for this article were accessed on September 1, 2021.

[2] The Fashion and Race Database features a rich bibliography and digital library on relevant scholarship across fields and subjects, in addition to two sections of original peer-reviewed content, “Objects that Matter,” and “Profiles.” http://www.fashionandrace.org. Jonathan Square’s “Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom,” can be found on Instagram at @fashioningtheself and online at https://www.fashioningtheself.com/.

[3] Elizabeth Holmes, “So Many Thoughts,” By Elizabeth Holmes, https://www.byelizabethholmes.com/so-many-thoughts.

[4] On the plantation system’s transformation of the European economy and connection to the origins of modern capitalism, see Trevor Burnard and John Garrigus, The Plantation Machine: Atlantic Capitalism in French Saint-Domingue and British Jamaica (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press: 2018); Pernille Røge, Economistes and the Reinvention of Empire: France in the Americas and Africa, c. 1750-1802 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019); and Caitlin Rosenthal, Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

[5] Future iterations of this course will benefit from this source, which had not been published when initially taught: Anna Arabindan-Kesson, Black Bodies, White Gold: Art, Cotton, and Commerce (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021). Also see: Steeve Buckridge, The Language of Dress: Resistance and Accommodation in Jamaica, 1760-1890 (Kingston, Jamaica: University of West Indies Press, 2004); Cécile Fromont, “Common Threads: Cloth, Colour, and the Slave Trade in Early Modern Kongo and Angolo,” Art History 41, 5 (2018), 838-867; Mireille Lee, “Antiquity and Modernity in Neoclassical Dress: The Confluence of Ancient Greece and Colonial India,” The Classical World 112, 2 (2019), 71-94.

[6] Amelia Rauser, The Age of Undress: Art, Fashion, and the Classical Ideal in the 1790s (New Haven: Yale University Press), 2020. Also see Amelia Rauser, “Vitalist Statues and the Belly Pad of 1793,” Journal18, Issue 3 Lifelike (Spring 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1373. DOI: 10.30610/3.2017.2.

[7] Gaby Gondinez, “This season of ‘Ru Paul’s Drag Race’ had a runway theme of ‘trains.’ Symone came to win THIS,” class assignment (Northwestern University, Spring 2021). Also see Pierre-Antoine Louis, “Symone Is a Love Letter to Blackness and Queerness,” New York Times (June 5, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/05/style/symone-rupaul-drag-race-winner.html.

[8] Momoe Anno, “The Muses from Disney’s ‘Hercules’ as an Unconscious Upheaval of 18th Century Europe’s Racialized Fashion Trends,” class assignment (Northwestern University, Spring 2021); Rhea Sharma, “An Analysis of Fenty x Puma Spring 2017 Show: in an 18th Century Context,” class assignment (Northwestern University, Spring 2021).

[9] Marlene L. Daut, “Why did Bridgerton Erase Haiti?” Avidly: a channel of the Los Angeles Review of Books (January 19, 2021), https://avidly.lareviewofbooks.org/2021/01/19/why-did-bridgerton-erase-haiti/.

[10] Rachel Syme, “The Allure of the Nap Dress, the Look of Gussied-Up Oblivion,” The New Yorker (July 21, 2020), https://www.newyorker.com/culture/on-and-off-the-avenue/the-allure-of-the-nap-dress-the-look-of-gussied-up-oblivion.

[11] Isabel Slone, “The Strawberry Dress That Ate TikTok,” The New York Times, August 18, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/18/style/strawberry-dress-tiktok-instagram-who-designed-where-to-get.html.

[12] The Museum of English Rural Life made this comparison explicitly on twitter, declaring Marie Antoinette a “Cottagecore icon.” @theMERL, “Right now, a lot of folks are talking about cottagecore, an aesthetic category romanticizing the rural idyll. This is (almost literally) our field of expertise. So, this morning, let’s chat cottagecore and, specifically, a cottagecore icon: uh, Marie Antoinette. [a thread],” Twitter, August 4, 2020, https://twitter.com/TheMERL/status/1290590669157867520.

[13] Meredith Martin, Dairy Queens: The Politics of Pastoral Architecture from Catherine de’ Medici to Marie-Antoinette (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011).

[14] Rebecca Jennings, “Once upon a time, there was cottagecore,” Vox.com, August 3, 2020, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2020/8/3/21349640/cottagecore-taylor-swift-folklore-lesbian-clothes-animal-crossing.

[15] Martin, Dairy Queens, 15.

[16] Leah Sinclair, “Black Women Embracing Cottagecore is an Act of Defiance,” Zora (August 25, 2020), https://zora.medium.com/black-women-embracing-cottagecore-is-an-act-of-defiance-3df8696d8811.

[17] Sarah Maslin Nir, “How 2 Lives Collided in Central Park, Rattling the Nation,” The New York Times (June 14, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/14/nyregion/central-park-amy-cooper-christian-racism.html.

[18] Despite this TikTok has not been an equitable space for black creators. Black TikTok dancers have recently boycotted the platform due to the continued plagiarism of their work. Moreover, TikTok’s hate speech detection tool is known to flag BLM content. It is notable that when @enchanted_noir uses the word racism in her TikToks she does not include the term in the closed captions for this precise reason. Also see, Sharon Pruitt-Young, “Black TikTok Creators Are On Strike to Protest A Lack of Credit For Their Work,” National Public Radio (July 1, 2021), https://www.npr.org/2021/07/01/1011899328/black-tiktok-creators-are-on-strike-to-protest-a-lack-of-credit-for-their-work; Shirin Ghaffary, “How TikTok’s hate speech detection toolset off a debate about racial bias on the app,” Vox News (July 7, 2021), https://www.vox.com/recode/2021/7/7/22566017/tiktok-black-creators-ziggi-tyler-debate-about-black-lives-matter-racial-bias-social-media.

Cite this article as: Alicia Caticha, “Some Thoughts on Fashion and Race in the Classroom; or, TikTok, Cottagecore, and the Allure of Eighteenth-Century Empire Style Dress”, Journal18, Issue 13 Race (Spring 2022), https://www.journal18.org/6211.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.