Zirwat Chowdhury

Contemporaries of the architect George Dance the Younger had little doubt that his new façade (built 1788-1790) for the City of London’s Guildhall (Fig. 1) made some form of reference to the artist Williams Hodges’s recently published views of Indian architecture (Fig. 2). As the City’s Clerk of Works (or surveyor), Dance oversaw the design, maintenance, and construction of its buildings and streets. Noting the façade’s “Gothic features,” the antiquarian Thomas Malton the Younger observed that “on the whole, [it] resembles the architecture of Hindostan [sic] more than any other.”[1] More pointedly, James Wyatt—a Gothic architecture enthusiast as well as Dance’s fellow architect and Royal Academician—chastised him for abandoning the “grammatical arts for flights of fancy… [by substituting] for true Gothic, something taken from the prints published by the artist Hodges” (emphasis mine).[2] The commentators’ comparison of Gothic and Indian architecture was likely informed by Hodges’s own theorization of the commensurability of the two. With the goal of attending more closely to this lens of comparison, this article situates Dance’s elusive translation of Hodges’s views within a ceremonial geography that celebrated both the City’s political freedoms—associated with key monuments of medieval, Gothic architecture—and its enrichment through imperial commerce.

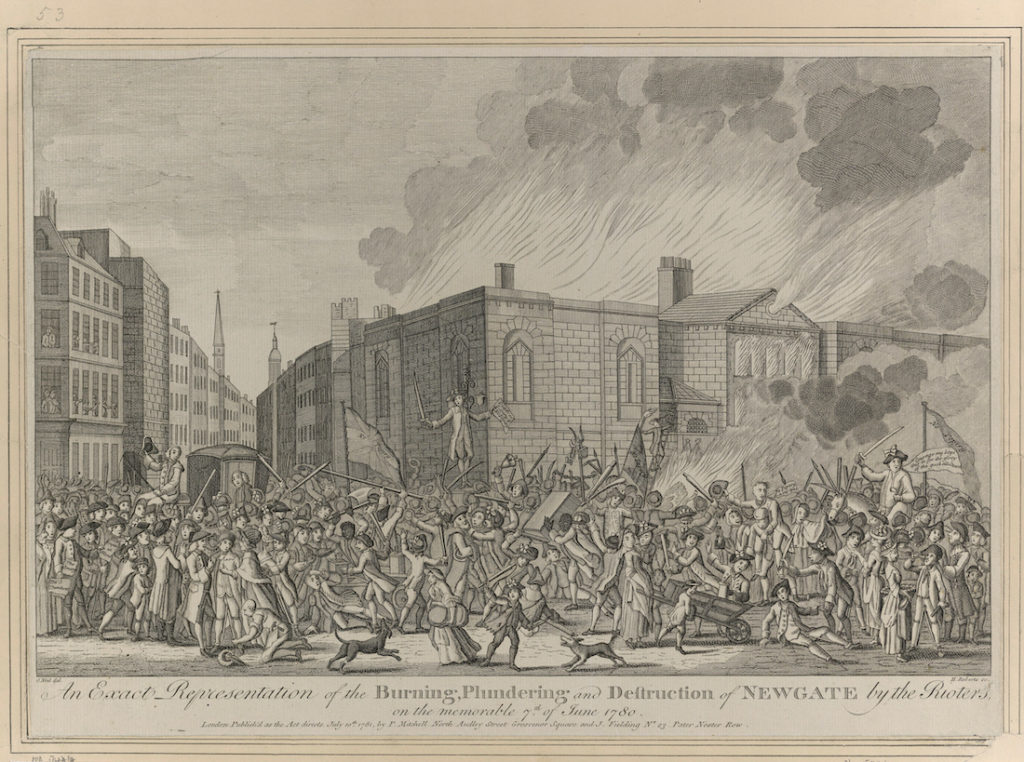

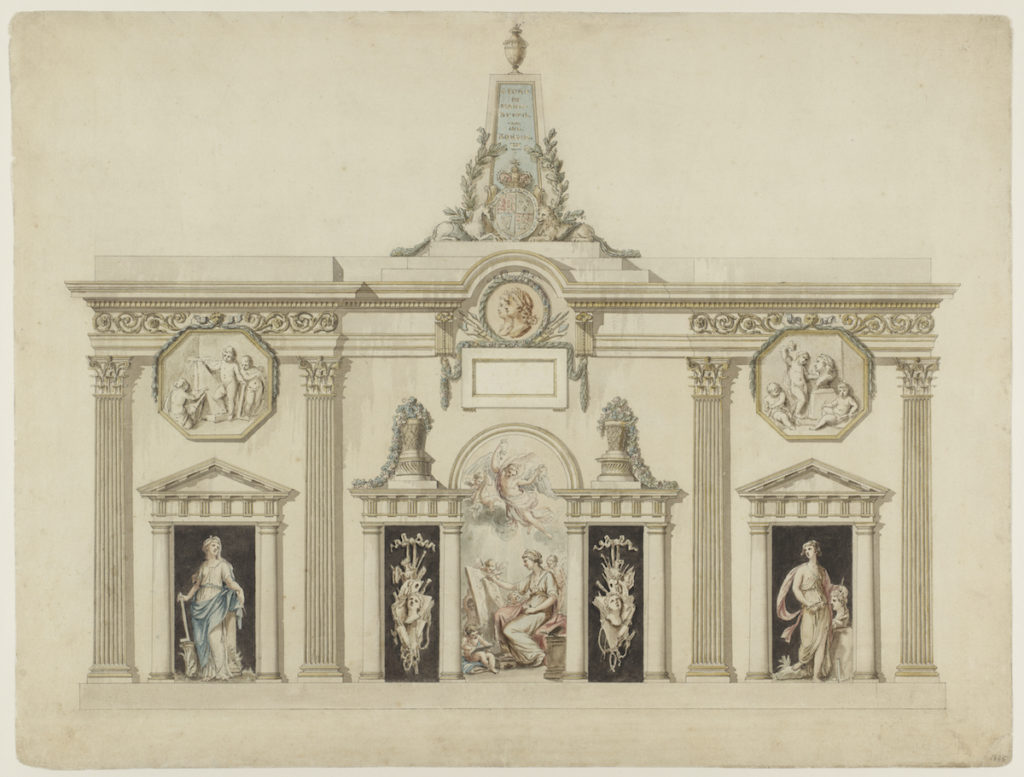

Such celebrations typically featured installations of ephemeral architecture and illuminations (Fig. 3) along the City’s streets. Given the mercurial politics of these streets, however, illumination festivities often carried the specter of arson. Indeed, Dance had only recently rebuilt his most monumental building project for the City—Newgate Gaol—after it was spectacularly burned down (Fig. 4) during the Gordon Riots in 1780 by protestors contesting laws that confirmed some rights for Britain’s colonial subjects. Dance, who appears to have been conversant in an emerging discourse of urban improvement that called for London’s transformation into a suitable capital for the British Empire, was thus also familiar with ongoing public debates about the forms of sovereignty that Britain should observe across its expanding and heterogeneous empire. Moving across the animated surfaces of the City’s streets and Hodges’s prints, this article draws attention to the flickering visual effect of Dance’s façade, arguing that it materialized the allure and risk of the fire that gave this emerging imperial capital its magnificent dazzle.

A Capital for the British Empire

Not to be confused with the larger urban entity now known as London, the City of London, or the Square Mile as it is also known, forms the British capital’s historical core. It is governed by the municipal corporation for its guilds or livery companies, and has represented London’s financial and commercial activities and interests since the medieval era. At its geographical heart stands Guildhall (Fig. 1), a fifteenth-century Gothic baronial hall that has been much renovated since its construction. It is where the City’s most important ceremonial event has culminated for centuries. Each year, the election of a new Lord Mayor, who heads the City, is observed with a procession from the City to Westminster (i.e. to Parliament) and back, and concluded with a spectacular banquet inside Guildhall.[3] Lord Mayor’s Day serves as a yearly enactment of the City’s “ancient liberties” or right to “its own political organization” in relation to Crown and/or Parliament, formally recognized in 1215 with the sealing of the Magna Carta.[4] The ceremonial geography of Lord Mayor’s Day—connecting two of London’s most prominent examples of medieval Gothic architecture, Guildhall and Westminster Hall (built 1097-1099, with subsequent renovations)—bolstered the association of such liberties with the Gothic style. Informed by a prevailing political and antiquarian discourse about Britain’s ancient and medieval past, Dance’s contemporaries thus understood Gothic architecture primarily as powerful relics of the chartered freedoms that Englishmen secured from intransigent monarchs.[5]

Guildhall was not just a meeting hall for conducting the City’s business and hosting its feasts, but a venerable reminder of its political history. Until the second half of the twentieth century, neighboring structures abutted or closely approached Guildhall on all sides, except on a portion of its south front. Overlooking a small plaza that was widened in the twentieth century, this part of the front has served throughout the building’s history as its public face. When Guildhall was damaged by the Great Fire of 1666—thereafter requiring the construction of a new roof and façade—efforts were made to retain as much of its earlier appearance as possible. Designing the new façade, Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke thus diverged little from the earlier medieval structure, though they added a prominent baroque pediment reminiscent of that which Wren had designed at Temple Bar.[6] They also retained the façade’s medieval porch that had survived the Great Fire and through which visitors entered Guildhall. When the seventeenth-century façade was damaged by a fire in one of the adjoining buildings in 1785, Dance was first tasked with salvaging it as best as possible.[7] Following multiple efforts to preserve it, he finally reported its irreparable state to the City and received authorization in June 1788 to provide a design for a new façade.[8]

While the decision to move ahead with a new façade was not without debate, a more prevailing criticism of the seventeenth-century façade had also garnered momentum since the 1760s.[9] Dance possessed in his library a copy of the noted bookseller Robert Dodsley’s architectural guide to London, published in 1761 as a lament for the city’s existing architectural landscape and call for greater urban magnificence.[10] Dodsley’s multivolume book contributed to, and even set the tone for, an emerging discourse that spoke of the urgency of managing the forces of imperial commerce that had begun to transform London’s urban spaces on the heels of the Seven Years’ War.[11] His assessment that “the Gothic front [of Guildhall] has nothing extraordinary about it” and that it is “full of little parts which have no effect at a distance” can be read as a foil for the aesthetic of magnificence that he championed throughout the book and that advocated instead for monumentality of scale, and dramatic but orderly visual contrasts of light and shadow. Dodsley selected Guildhall among those sites most in need of transformation, as it “had an advantage hardly to be met with elsewhere,” and would “give an architect a fine opportunity of displaying his genius.”[12] The advantage to which he referred was that the façade could be “viewed at a good distance from Cheapside, the most frequented thoroughfare in the city.”[13] Cheapside was also the location for the pageantry and returning procession on Lord Mayor’s Day.

If Cheapside had featured prominently since the medieval era in a ceremonial geography commemorating the City’s political and commercial liberties, its streets also celebrated the City’s enrichment from early modern global trade with pageants featuring allegories of the four continents and images of cornucopia.[14] As Mireille Garandon has discussed, by the early eighteenth century the figure of the English merchant was largely defined in terms of his association with global commerce.[15] Studies of merchants’ homes in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century City reveal extensive collections of goods from the regions of the East Indies.[16] That asymmetric relations of power were already beginning to inform the portrayals of such global commerce at the pageants can be seen in a drawing by Anthony Walker (Fig. 5), an artist who apprenticed in the City and made several prints about its political and ceremonial cultures in the 1750s. Walker’s allegories of Africa, Asia, and the Americas—the continents then known to Europeans—are set apart from that of Britannia, to whom they offer their tribute, through differences in costume, states of undress, facial structures, and skin tone. The kneeling pose of the figure of Africa vividly foregrounds the dynamics of conquest and submission, even as it conceals the forces of violence that drove the culture of imperial trade championed in this drawing.

As the City’s pageants attested, the successes of Britain’s overseas commerce had become increasingly inseparable from the triumphs of war. Writing of the ephemeral arches that decorated City streets during festivities, Christine Stevenson argues that their aesthetic of reuse and assembly not only celebrated the craftsmanship that was the strength of the City’s guilds, but also resonated with the translation of spolia, or the triumphant display of the spoils of war, as ornament within classical architecture.[17] In his study of the East India Company (EIC), whose headquarters stood in the City, Philip Stern has shown how the reach, fortunes, and misfortunes of its early modern commerce hinged on its ability to wage war and orchestrate peace overseas.[18] Dance appears to have had his own interest in the mechanisms and consequences of global commerce, as his possession of James Capper’s Observations on the Passage to India (1785) indicates.[19]

In his text, Capper reminded readers that although trade with Egypt had greatly enriched the Roman Empire, Egypt owed its own affluence to trade with India. He contended that it was Indian navigational ingenuity that had brought Indian goods to Egypt and laid the foundations for the land and sea routes that connected the Eastern Mediterranean to India.[20] Attributing the decline of Egypt to the decline of trade with India, he argued that “whatever nation has possessed the largest share of it, has invariably for the time enjoyed also the largest portion of wealth and power; and when deprived of it, sunk again almost into their original obscurity.”[21] Tracing the history of commerce from antiquity to the modern era via the Crusades, Capper mapped out a transfer of Indian trade from Egyptian, to Venetian, to Portuguese, to Dutch, and, finally, in the eighteenth century, to victorious English hands.[22] Providing an antiquarian genealogy to the East Indies trades, Capper offered readers like Dance a powerful defense of global trade that not only positioned India as the source of Britain’s commercial prosperity, but also endowed this relationship with the authority of antiquity.

Dance provided the design for his new, three-bay façade in the presentation drawing that accompanied the builder’s contract on July 9, 1788 (Fig. 6).[23] His design introduced crenellation and transformed the trefoiled niches of the seventeenth-century façade into neat rows of windows, while also incorporating fluted piers that rose into turrets with finials resembling narwhal tusks.[24] In addition, it organized the small floral ornaments that dotted the seventeenth-century façade into long bands that now stretched across the width of the new design.[25] Of note, too, is Dance’s replacement of the earlier baroque pediment—replete with associations of absolute monarchy—with the City’s coat of arms. Dance made two final changes to the façade during construction: he modified the trefoils into cinquefoils, and replaced the narwhal tusks with oval finials and polygonal turrets.[26] As parade participants processed through Cheapside on Lord Mayor’s Day and arrived at Guildhall for the culminating feast, Dance’s new façade, with its three-bay organization and arched entrance, would have echoed the form of the ephemeral arches on the streets.[27] Moreover, with its collective interventions—retaining the venerable medieval porch, repurposing material from the earlier structure, and combining different architectural forms such as Venetian crenellation and Gothic cinquefoils—Dance’s façade recalled the ephemeral arch’s imperial aesthetic of reuse and assemblage. The imperial dimension was especially significant because, as Wyatt noted, the façade appeared to have also taken, or spoliated, “something” from Hodges’s Indian views.

Untrue Gothic

Between 1786 and 1788, Hodges published large-scale aquatints in his two-volume Select Views in India, Drawn on the Spot, in the years 1780, 1781, 1782, and 1783, one of the first major visual compilations of Indian architecture in Britain.[28] Views of crenellated, tripartite, monumental gateways with pointed niches and windows—forms echoed by Dance’s façade—feature prominently across Hodges’s two volumes. The artist had first made his name as the draftsman on the second Cook voyage (1772-1775). From 1780 to 1783, he traveled extensively across northern India, in many instances under the patronage of Warren Hastings, Governor General of the EIC between 1773 and 1785. Following his return to Britain, Hodges exhibited paintings of his Indian views at the Royal Academy of Arts and published Select Views.[29] The volumes’ prefatory essay, entitled A Dissertation on the Prototypes of Architecture, Hindoo, Moorish and Gothic, added to prevailing opinions about the eastern origins of Gothic architecture. [30] It invited readers to shed their blind allegiance to classical architecture and pay closer attention to the shared typologies of Gothic architecture and the examples of Indian architecture that Hodges encountered during his travels. Prefaced with this comparative stylistic theory, Hodges’s views are likely to have provided Dance with an architectural reference that could resonate with both the City’s Gothic architectural history and its deepening investment in Britain’s imperial relations with India.

Within the pages of Select Views, Hodges offered his most thorough explication of his thesis on Gothic architecture in a description of A View of a Mosque at Chunar Gur, observing that:

This view is given as a remarkable instance of the perfect similarity between architecture of India, brought there from Persia by the descendants of Timur, and that brought into Europe by the moors seated in Spain, and which afterwards spread itself through all the western parts of Europe, known by the name of Gothic architecture. The general forms of this building, as well as many others in India, are the same as those we see in Europe. In this all the minuter ornaments are perfectly the same – the lozenge square filled with roses, the ornaments in the spandrels of the arches, the little paneling, and their mouldings, that a person would almost be led to think that artists had arrived from the same school at the same time, to erect similar buildings at the extremity of India and of Europe (emphasis mine).[31]

In the accompanying print (Fig. 2), Hodges rendered the building with a more pointed arch and created an effect of asymmetry by including a foliated wall on the lower right, thereby endowing the view with two characteristics that eighteenth-century British audiences conversant in the aesthetic discourse of the picturesque often associated with Gothic architecture. The print does not, however, entirely reaffirm Hodges’s written description: moving from text to image, the reader would be disappointed to find illegible architectural ornaments rendered as blotted marks of ink rather than “lozenge square(s) filled with roses,” reflecting a more general lack of precision for which Hodges’s prints were criticized.[32] Hodges himself noted the limitations and possibilities of the two print media—aquatint and engraving—that he used in Select Views, alerting his readers to the affective dimensions of aquatint in contrast to the precision of detail afforded by line engraving.[33]

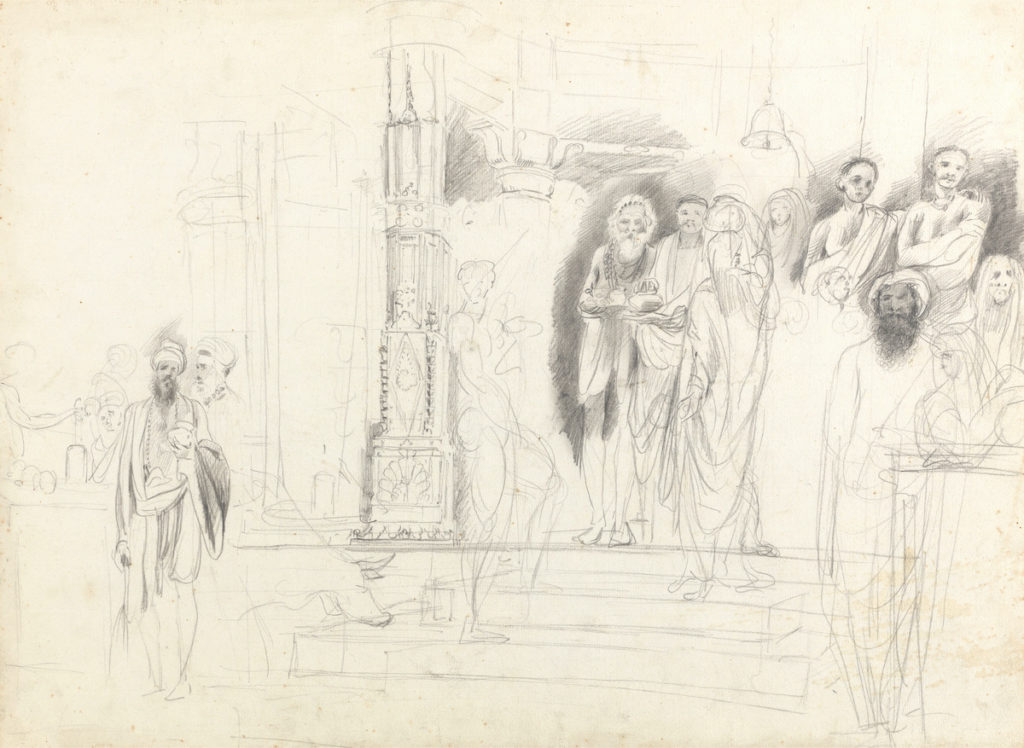

The artist offers his greatest architectural detail in an engraving of a column—based on a detail from a graphite sketch in his travel album—that accompanies a reprint of the Dissertation in a travelogue he published in 1793 (Fig. 7). The sketch shows a gathering of priests and worshipers, along with the faint outlines of a cow in their midst, at the entrance to the newly constructed Vishweshwur Temple in Banaras (Fig. 8).[34] The travelogue’s description of how Hodges’s attention kept being drawn to the seemingly familiar ornaments of the column mirrors the process of visual attunement captured in the drawing.[35] The drawing’s variety of pencil marks—shadows and details fill in some contours while leaving others as draftsmanly apparitions—allows the viewer to trace the acts of attention through which Hodges distills from a scene of moving bodies the column that, per classical European conventions, would stand for the temple’s architectural order. The modulation of polygonal forms in the column’s shaft, especially the effect of fluting, finds an echo in the façade’s polygonal turrets (Fig. 9). Even Dance’s cinquefoil windows and half paterae recall the form of the column’s floriated base.[36] Hodges did not publish the column engraving until 1793. Given the striking resemblance of Dance’s turret to it, it is plausible that the architect would have known the drawing through some personal contact in London with his fellow Academician.[37]

As Hodges published the last of his aquatints, Hastings, his patron, was impeached and put on trial at Westminster Hall between 1788 and 1795 on charges of bribery, disregard for the sovereign status of Indian rulers, and excessive use of military force.[38] The trial frequently discussed events that took place in sites portrayed in Hodges’s views, including Chunar Gur. Edmund Burke, who led the prosecution of Hastings in the name of justice for Indians, had long voiced his concerns about the abuses of British liberty across the expanding breadth of Britain’s “disjointed empire,”[39] calling one regulatory measure against the EIC that he unsuccessfully supported in 1783 the “Magna Carta of Hindostan.”[40] Indeed, he summarized the premise of Hastings’s trial as an “inquest” for justice on behalf of peoples who, although living across the seas at a great distance from Britain, were nonetheless “united [to it] by bonds of social and moral community.”[41] Burke’s invocation of the Magna Carta and the rights of Indians underlines the trial’s deliberation of a critical political concern: whether or not Indians were subjects of and thus claimants upon Britain’s Gothic liberties. As he pleaded, shifting his audience’s attention from a local to a global geography:

It is not from this district, or from that parish, not from this city, or the other province, that relief is now applied for: exiled and undone princes, extensive tribes, suffering nations, infinite descriptions of men, different in language, in manners, and in rites—men, separated by every barrier of nature from you, by the providence of God are blended in one common cause, and are now become suppliants at your Bar (emphasis mine).[42]

As Dance had learned earlier in the decade, however, lingering on the edge of such declarations of Gothic liberty was also the danger of fire or Gothic terror.[43]

Fireproof Architecture

In 1780, protestors demanding the repeal of two laws that had been recently passed burned down Dance’s newly completed Newgate Gaol (built 1769-1777) and released other protestors who had earlier been imprisoned there (Fig. 4).[44] Following the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), British administrators explored different avenues for governing the heterogeneous polities existing within territories that it had gained overseas. Among these, they enacted the Quebec Act (1774) and Catholic Relief Act (1778) to extend the rights of Catholics in Britain and the British Empire.[45] While the first law fostered inclusion of Catholics in a colony struggling to find settlers, the second permitted Catholic military conscription. To critics, the first welcomed the subversion of English, Protestant liberties, while the second enabled the government to circumvent the refusal of many British Protestants to fight their American brethren during the Revolutionary War through the conscription of Catholics into the military.[46] Although the Gordon Riots, as these events came to be called, were the only large-scale political insurrection pertaining directly to matters of Britain’s overseas empire to take place on British soil in the eighteenth century, the burning of Newgate stood in a longer history of arson and architectural destruction that is not easily disentangled from the City’s festivities.

From the early eighteenth century, London’s streets were transformed yearly during major festivities with architectural illuminations or nighttime decorations that featured lighting alone or in combination with transparencies (Figs. 3 and 10). Transparencies were paintings on thin surfaces that, when back-lit, offered the advantage of visibility against the dark contrast of night.[47] The flickering of candles and lamps would have added an animating effect to the painted representations. The British Ambassador to Naples, Sir William Hamilton, reported to the Royal Society in 1766 how transparencies captured the liveliness of Mount Vesuvius’s eruption.[48] Architectural transparencies created for major public occasions, such as that made by Giovanni Battista Cipriani and Sir William Chambers for the Royal Academy during the king’s birthday in 1771 (Fig. 10), were typically monumental single- or multi-figure compositions. In the City, illuminations were usually displayed at Mansion House (the Lord Mayor’s residence) and the Bank of England, and they were often reused.[49] In January 1783, The British Magazine and Review praised the illuminations that were displayed at the Lord Mayor’s pageant, especially the lifelike effect of the allegorical figures of commerce.[50]

Facing Cheapside, Guildhall’s façade mediated an affective coexistence with its passersby, wherein the pleasures of illumination could just as easily descend into the risk of conflagration. City residents were often asked to decorate the windows of their homes and shops on illumination nights, risking the ire of passersby if they failed to do so.[51] Indeed, over the course of the eighteenth century, both street festivities and protests were more and more often accompanied with the destruction of architecture. As Nicholas Rogers has shown in his overview of Tory and Whig street contestations, the official calendar of ceremonies also opened possibilities for an event’s subversion and contestation.[52] For example, supporters of the journalist and politician John Wilkes broke every window at Mansion House in 1768 amid the Parliamentary controversies of that year.[53] Dance not only witnessed the destruction of Newgate Gaol, but was also tasked throughout his career with repairing architectural damages incurred across the City and fireproofing its architectural spaces.[54] In addition to fireproofing experiments that he conducted near Guildhall, Dance introduced an iron-plated ceiling at the Shakespeare Gallery, which he built around the same time as Guildhall’s new façade.[55] In July 1789, when the City authorized him to construct a new story over the porch with a room for storing its deeds and records, it also approved the use of Hartley fireplates.[56]

Dance’s preoccupation with fire was not limited to his innovations for the material fabric of the new façade. Indeed, he seems to have incorporated the flickering effect of architectural illuminations into the façade’s design. When imagined within a streetscape of illuminations, the cinquefoil windows of Dance’s façade take on a distinctly flamelike appearance. The pointed and scalloped edges of the turrets appear to set alight the long piers on which they stand, and whose flutes convey a play of light and shadow across their curved surfaces. Two years before Dance began his redesign of Guildhall’s façade, Sir Joshua Reynolds, then President of the Royal Academy, advised architects to look to Hodges’s views for “hints of composition, and general effect” rather than as “models to copy.”[57] Reynolds’s words offer an insight that is useful in teasing out Dance’s somewhat elusive reference to Hodges’s prints. While Hodges’s View of a Mosque at Chunar Gur (Fig. 2) may have failed to offer its viewers a panoply of architectural detail, its combination of aquatint and hand-coloring gave the print a vibrancy by accentuating contrasts in tone with gradations in color.[58] In his discussion of how the medium of aquatint transformed the genre of the travel book, Douglas Fordham attends to aquatint’s creation of mood with its reproduction of wash-like effects.[59] Drawing, as he himself claimed, “on the spot,” Hodges supplanted what his prints did not provide in terms of architectural detail by addressing, instead, the viewer’s sense of perception.[60] The layering of darker greens over lighter ones for the rendering of the foliage on the left, allowing the lighter colors to peek through, makes the edges of the print appear to dissolve. The strong shadow in the foreground and the velvety richness of the hand-colored trees endow the gateway at the center with a luminosity much like that of a back-lit transparency. While the crenellated, tripartite “Gothic” architectural forms of Hodges’s Indian views may have provided Dance with an architectural reference that could mediate between the City’s Gothic architectural history and imperial commerce, the prints’ transparency-like effects also complemented the allure and danger of the fire that gave the City’s streets their spectacular character. In addition to fireproofing it with Hartley plates, Dance endowed his new façade with the almost apotropaic effect of illumination.

Conclusion

Within the historiography of British architecture and the British Empire, Dance’s façade is noted as one of the first examples of architecture in Britain to make reference to Indian architecture.[61] However, like Dance’s contemporaries, historians have been tentative in explicating the line of reference between the façade’s appearance and any material and visual conventions associated with Indian architecture. Instead, they have leaned on Britain’s growing imperial presence in India as a point of causality. As this article has shown, Hodges’s Indian views were, indeed, created within Britain’s expanding imperial infrastructure in India. Of note, too, is how the architectural forms and visual effects of the artist’s prints resonated with the vexed culture of imperial pageantry on the City’s streets. Taking “something” from Hodges’s prints, Dance appears to have prevented another fire in the City by, in effect, setting his new façade for Guildhall alight.

Zirwat Chowdhury is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to Chanchal Dadlani, Ünver Rüstem, Anne Helmreich, and the two anonymous editors for their invaluable feedback during the writing of this article.

[1] Thomas Malton, A Picturesque Tour Through the Cities of London and Westminster, illustrated with the most interesting Views, accurately delineated, and executed in Aquatinta, 2 vols.(London: Thomas Malton, 1792-1801), 1:73.

[2] James Wyatt in Dorothy Stroud, George Dance: Architect, 1741-1825 (London: Faber & Faber, 1971), 121.

[3] To minimize disruption of traffic, the procession now takes place on Saturdays, with the feast occurring on the following Monday. Peter Blundell Jones, Architecture and Ritual: How Buildings Shape Society (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), 52.

[4] Jones, Architecture and Ritual, 45-66; Bridget Cherry, “London’s Public Events and Ceremonies: An Overview Through Three Centuries,” Architectural History 56 (2013), 1-28; David Bergeron, English Civic Pageantry, 1558-1642 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1971); Sheila Williams, “The Lord Mayor’s Show in Tudor and Stuart Times,” Guildhall Miscellany 10 (Sept. 1959, 3-18; and Tracy Hill, Pageantry and Power: A Cultural History of the Early Modern Lord Mayor’s Show, 1585-1639 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010).

[5] J.G.A. Pocock, “Civic Humanism and Its Role in Anglo-American Thought,” in Politics, Language, and Time: Essays on Political Thought and History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), 94-95; and Owen Hopkins, “Hawksmoor and the Gothic,” in Gothic Legacies: Four Centuries of Tradition and Innovation in Art and Architecture, eds. A. Lepine and L. Cleaver (Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012), 158-181. With the onset of industrialization, the discourse of nineteenth-century Gothic Revival architecture was formulated largely in critique of the aesthetic and corporeal debasement of industrial life and labor. For the different aesthetic and political commitments of the nineteenth-century Gothic Revival movements, especially the restaging of “feudal relations” in the colonial durbars in India, see Timothy Barringer, Men at Work: Art and Labour in Victorian Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 243-312.

[6] Emily Mann, “In Defence of the City: The Gates of London and Temple Bar in the Seventeenth Century,” Architectural History 49 (2006), 90. A rich and comprehensive history of the various building phases of the Guildhall (with a reconstruction of its Wren/Hooke façade that convincingly disputes its eighteenth-century drawing and print representations) is provided in David Bowsher et al., The London Guildhall: An Archaeological History of a Neighbourhood from Early Medieval to Modern Times, 2 vols.(London: Museum of London Archaeology, 2007). For a consideration of how Guildhall was likely designed by Hooke alone, see Matthew F. Walker, “The Limits of Collaboration: Robert Hooke, Christopher Wren and the Designing of the Monument to the Great Fire of London,” Notes & Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 65 (June 2011), 121–143.

[7] Two invaluable resources on Dance’s conservation and redesign of the façade, including astute discussions of his architectural drawings, are Stroud, George Dance, 119; and Jill Lever, Catalogue of the Drawings of George Dance the Younger (1741-1825) and of George Dance the Elder (1695-1768): From the Collection of Sir John Soane’s Museum (London: Azimuth Editions on behalf of Sir John Soane’s Museum, 2003).

[8] June 4-19 in London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), City of London, COL/CC/06/01/0257, Corporation of London Collection.

[9] William Prickett, who served as Lord Mayor in 1789, voiced his opposition to the tearing down of Guildhall in Public improvement; or, a plan for making a convenient and handsome communication between the cities of London and Westminster (Cornhill: J. Bell, 1789), 51. The Public Gazetteer reported on June 21, 1788 that debates had taken place at the Guildhall about whether or not the south front should be taken down, before Dance’s plans for a new façade were finally approved.

[10] Robert Dodsley, London and Its Environs Described…, 6 vols. (London: R. and J. Dodsley, 1761). For an overview of the eighteenth-century improvement discourse, see Alison O’Byrne, “Composing Westminster Bridge: Public Improvement and National Identity in Eighteenth-Century London,” in The Age of Projects, ed. Maximilian Novak (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), 243-270.

[11] One notable instigation for London’s urban redesign came from John Gwynn, London and Westminster improved, illustrated by Plans, to which is prefixed a Discourse on Public Magnificence, with Observations on the state of Arts and Artists in this Kingdom (London, 1766). For more on urban planning in Georgian London and the aesthetic of magnificence, see Miles Ogborn, Spaces of Modernity: London’s Geographies, 1680-1780 (London: Guilford Press, 1998), 79, 91-104; and John Bonehill, “The Centre of Pleasure and Magnificence”: Paul and Thomas Sandby’s London,” Huntington Library Quarterly 75:3 (2012), 365-392. For contestations between a mercantile culture of the street and imperial forces of improvement during the Seven Years’ War, see Douglas Fordham, British Art and the Seven Years’ War: Allegiance and Autonomy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 103-154.

[12] Dodsley, London and Its Environs Described, 3:105.

[13] Malton, A Picturesque Tour Through the Cities of London and Westminster, 2:73.

[14] Zirwat Chowdhury, “Blackness, Immobility & Visibility in Europe: A Digital Collaboration,” Journal18 (September 2020), https://www.journal18.org/5199.

[15] Mireille Galinou, “Introduction,” in City Merchants and the Arts, 1670-1720, ed. Mireille Galinou (London: Oblong Creative Ltd. For the Corporation of London, 2004), x.

[16] David Mitchell, “A Passion for the Exotic,” in City Merchants and the Arts, 69-82.

[17] Christine Stevenson, “Occasional architecture in Seventeenth-Century London,” Architectural History 49 (2006), 35-74.

[18] Philip J. Stern, The Company-State: Corporate Sovereignty and the Early Modern Foundation of the British Empire in India (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[19] James Capper, Observations on the Passage to India, through Egypt. Also by Vienna through Constantinople to Aleppo and from thence by Bagdad, and directly across the Great Desert, to Bassora. With Occasional Remarks on the adjacent Countries, an Account of the Different Stages, and Sketches of the Several Routes on Four Copper Plates (London: W. Faden, J. Robson, and R. Sewell, 1785). For a list of Dance’s books, see Auction Catalogue of the Architectural and Miscellaneous Library of the Late George Dance (London: R.H. Evans, 1837).

[20] Capper, Observations on the Passage to India, 45-46.

[21] Capper, Observations on the Passage to India, 54.

[22] Capper, Observations on the Passage to India, 55-56.

[23] Elevation and Contract for south front, dated July 9, 1788 in LMA, City of London, COL/SVD/PL/06/0083, Corporation of London collection.

[24] Plausibly a reference to maritime trade and the culture of curiosity born of it.

[25] The floral ornaments were to be fashioned of Coade stone. The contract indicates that these were to be laid with iron, and the finials or turrets covered with copper. Fireproofing appears to have been a central concern of the builders’ contract. LMA, City of London, COL/SVD/PL/06/0083, from the Corporation of London collection.

[26] That the contract named the City’s arms and the spires as parts not included within its scope suggests that Dance may have still been finalizing those components of the design. Whereas the builder’s contract targeted completion of construction by September 1789, the final accounts were not settled until January and July 1790, and at almost twice the cost of the original contract. See LMA, City of London, COL/CC/06/01/0260, Corporation of London Collection.

[27] Howard Colvin, “Pompous Entries and English Architecture,” in Essays in English Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 67-93; and Stevenson, “Occasional architecture in Seventeenth-Century London,” 35-74.

[28] The volumes were a costly affair that also incurred a financial loss.

[29] Geoff Quilley and John Bonehill ed., William Hodges: The Art of Exploration, 1744-1797 (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2005); Giles Tillotson, The Artificial Empire: The Indian Landscapes of William Hodges (Richmond: Curzon, 2000); and Natasha Eaton, Mimesis Across Empires: Artworks and Networks in India, 1765-1860 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 105-150.

[30] William Hodges, Select Views in India, Drawn on the Spot, in the years 1780,1781, 1782, and 1783 (London: Printed for the Author, 1786-1788).

[31] William Hodges, Travels in India during the years 1780, 1781, 1782 and 1783 (London: Printed for the Author, 1793), 45-46.

[32] Thomas and William Daniell, who published a more extensive and detailed repertoire of architectural views from India a few years later, dismissed Hodges’s views for their lack of architectural precision. See Tillotson, The Artificial Empire, 42. The Daniells were in India, conducting their first trip outside Calcutta, during the reconstruction of Guildhall. Dance does not seem to have made their acquaintance until after their return to Britain, as any existing evidence of their exchange and collaboration postdates 1794, including Dance’s attendance of one of Thomas’s dinners in 1805. National Art Library MSL/1979/5116/1.

[33] Douglas Fordham rightly notes that the artist elided architectural detail even in the two, large-scale copperplate engravings by John Browne and Thomas Morris that he published with the Dissertation. See Fordham, Aquatint Worlds: Travel, Print, and Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 46-49. For more on the engravings, see Stephen Bann, “Antiquarianism, Visuality, and the Exotic Monument,” in Traces of India: Photography, Architecture, and the Politics of Representation, 1850-1900, ed. Maria Antonella Pelizzari (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 60-85.

[34] Contrary to Hodges’s ruinous or idyllic views, Madhuri Desai has shown in her comprehensive study of Banaras’s architectural fabric that the city thrived owing to a renewed emphasis on architectural patronage. The patron of the new Vishweshwur Temple was Rani Ahilyabai Holkar, the widowed daughter-in-law, and successor of the Mahratta Chief of Malwa, Mahallrao Holkar. Madhuri Desai, Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017).

[35] Hodges (1794) in G. H. R Tillotson, “The Indian Travels of William Hodges,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Third Series, 2:3 (1992), 389.

[36] My thanks to Jacob Lewis for noticing this.

[37] Dance included a portrait of Hodges in his major portrait project in the late 1790s, but I know of no other documentation of their artistic exchange prior to that.

[38] P.J. Marshall, The Impeachment of Warren Hastings (London: Oxford University Press, 1965).

[39] Edmund Burke, “Speech in Opening the Impeachment of Warren Hastings, Esq.: First Day, 15th February, 1788,” in On Empire, Liberty, and Reform: Speeches and Letters, ed. David Bromwich(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 390.

[40] Burke, “Fox’s East India Bill,” in On Empire, Liberty, and Reform: Speeches and Letters, 292.

[41] Burke, “Speech in Opening the Impeachment of Warren Hastings,” 382, 398.

[42] Burke, “Speech in Opening the Impeachment of Warren Hastings,” 390.

[43] Burke is also one of the most important commentators on the aesthetics of terror, which he discusses at length in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful, ed. Paul Guyer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[44] Simon Devereaux, “Recasting the Theatre of Execution: The Abolition of the Tyburn Ritual,” Past & Present 202 (2009), 127-174. For how prints portraying the burning of Newgate likely drew on conventions set by Wenceslaus Hollar’s prints of the Great Fire of London, see Ian Haywood, “‘A Metropolis in Flames and a Nation in Ruins:’ the Gordon Riots as Sublime Spectacle,” in The Gordon Riots: Politics, Culture and Insurrection in Late Eighteenth-Century Britain, eds. Ian Haywood and John Seed (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012),117-143.

[45] Hannah Weiss Muller, Subjects and Sovereign: Bonds of Belonging in the Eighteenth-Century British Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[46] Jeffrey L. Spear, “Of Jews and Ships and Mob Attacks, Of Catholics and Kings: The Curious Career of Lord George Gordon,” Dickens Studies Annual 32 (2002), 71. For how the seemingly asymmetrical ideological forces of free trade and colonial subjugation together constituted British imperial ideology under the banner of Protestantism, see David Armitage, Ideological Origins of the British Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). For the protestors’ criticism of the severity of the Georgian penal code, see Haywood, “‘A Metropolis in Flames and a Nation in Ruins,” 117.

[47] Melanie Doderer-Winkler, Magnificent Entertainments: Temporary Architecture for Georgian Festivals (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 2, 113-119; and Alice Barnaby, Light Touches: Cultural Practices of Illumination, 1800-1900 (London: Routledge, 2017), 105. For a succinct discussion of the nature of transparencies, see Anita Callaway, Visual Ephemera: Theatrical Art in Nineteenth-Century Australia (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2000), 7-8.

[48] Kevin Salatino, Incendiary Art: The Representations of Fireworks in Early Modern Europe (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 1997), 56.

[49] Doderer-Winkler, Magnificent Entertainments, 135.

[50] W. Wood ed., The British Magazine and Review, or Universal Miscellany, 3 vols. (London: Harrison & Co, 1782-1783), 2:62.

[51] Sources refer primarily to interior decorations at Guildhall, although it very well may have been decorated on its exterior as well. Barnaby, Light Touches, 105.

[52] He also observes that street festivities were increasingly transformed in the nineteenth century from participatory events to ones that encouraged passive viewing. Nicholas Rogers, “Crowds and Political Festival in Georgian England,” in The Politics of the Excluded, c. 1500-1850, ed. T. Harris (London: Palgrave, 2001), 247-256.

[53] George Rudé, “The London ‘Mob’ of the Eighteenth Century,” The Historical Journal 2:1 (1959), 3.

[54] George Rudé contrasts the City’s high repair costs following damages from protests with the loss of work and high living costs that the City’s more precarious artisans faced. He also contends that while protestors often revealed xenophobic and chauvinistic leanings, their alignments were far from universally consistent. See Rudé, “The London ‘Mob’,” 1-18.

[55] Michael Hugo-Brunt, “George Dance, the Younger, as Town Planner (1768-1814),” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 14:4 (1955), 22, fn. 38; and Richard Altick, The Shows of London (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978), 107.

[56] July 1789 in London Metropolitan Archives, City of London, COL/CC/06/01/02600, Corporation of London collection.

[57] This is of particular note, as Reynolds’s lecture is largely written in homage to the early eighteenth-century architect John Vanbrugh, whose travels to India are almost never mentioned in the period sources that remain. Sir Joshua Reynolds, “Discourse XIII,” in Discourses on Art, ed. Robert Wark (New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art, 1997), 242-243.

[58] As Hodges’s prints elucidate, and as Fordham demonstrates in his examination of William Daniell’s subsequent experiments in the medium, accuracy of architectural detail without the mediation of line engraving posed an altogether different challenge. Fordham, Aquatint Worlds, 67-70.

[59] Fordham, Aquatint Worlds, 33, 35.

[60] The most well-known of the Royal Academy artists to explore this relationship between light and perception was Thomas Gainsborough, especially in his transparent paintings on glass. Ann Bermingham, “Gainsborough’s Cottage Door: Sensation and Sensibility,” in Sensation and Sensibility: Viewing Gainsborough’s Cottage Door, ed. Ann Bermingham (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 1-34.

[61] Raymond Head observes that the Guildhall façade’s “design affords a striking artistic parallel to a then-current political idea about British relations with India,” notably as one of the “assimilation of Indian elements with Gothic,” in The Indian Style (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986), 22. A similar approach is taken by John Sweetman, The Oriental Obsession: Islamic Inspiration in British Art and Architecture, 1500-1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 73-111. See also John Summerson, Georgian London (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1978), 149.

Cite this article as: Zirwat Chowdhury, “George Dance the Younger Sets Guildhall Alight,” Journal18 Issue 11 The Architectural Reference (Spring 2021), https://www.journal18.org/5665.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.