William N. Goetzmann and Darius A. Spieth

In an influential study of the mechanisms of absolutist power, Louis Marin compared the icon of Jansenism, Philippe de Champaigne’s Christ on the Cross (Fig. 1), to the Sun King’s official state portrait by Hyacinthe Rigaud (Fig. 2):

Compare two figures of the body in order to link them to each other indissolubly: the royal body and the divine body. […] These two images, the two volets of the diptych, when put back-to-back become the front and back sides of the same painting—indeterminably hidden and revealed, front and back.[1]

One could argue that the palace of Versailles and the financier John Law’s Banque Royale in Paris, and their respective decorative programs, represent similar “volets” of a diptych of absolutist power, although the latter hinges on colonial conquest and finance rather than religion and reason of state. And whereas Versailles, by virtue of still being extant, continues to make the workings of absolutism tangible to the present age—the mere size of the buildings and their axiality, the centrality of the figure of the king, the display of surplus wealth through chandeliers, mirrors and gold, and, finally, the favoritism encapsulated in the architectural form of the Hall of Mirrors—Law’s Banque Royale remains hidden in the shadows of history, mainly because its representative core, the ceiling painting of the Salle du Mississippi, did not survive much beyond the lifetime of its patron and sponsor.

Right: Fig. 2. Hyacinthe Rigaud, Portrait of Louis XIV in his Majesty, 1701. Oil on canvas, 277 x 194 cm. Paris, Louvre, inv. 7492. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini’s ceiling decoration of the Salle du Mississippi, which graced the grandiose boardroom of the Banque Royale, has been described as “the great lost work of modernity, for it was the first and only attempt ever to portray money as grace [and] to glorify a financial enterprise in the pictorial language of absolutism.”[2] Measuring 42 x 9 meters—roughly equal in width and more than half the length of the Hall of Mirrors—the artwork was as ephemeral as it was monumental. Commissioned by Law in November 1719 and completed in the spring of 1720, at the height of his Mississippi scheme, the ceiling’s complex allegorical program depicted his vision of a state-sponsored global trading monopoly bringing the wealth of a connected world to French shores. These material benefits were further enhanced by the promise of a new political and economic order based on peace and commerce.

The Law “system,” as his plan was called, demanded a skillful and imaginative interpreter. The Venetian artist Pellegrini was one of the foremost illusionistic ceiling painters of the age and had spent much of the preceding decade executing prestigious commissions for decorative murals in statehouses, country homes, and churches in continental Europe and Great Britain. A work on the scale of the Salle du Mississippi would invariably invite comparison to the Hall of Mirrors, not only because of its size, but also because of the central role that its decorative scheme played in the representation of sovereign authority. Space, whether real or illusionistic, was the manifest representation of absolutist power. No doubt, the audience for the Salle du Mississippi—the board members of the Banque Royale and the Regent Phillippe II—was intimately familiar with the visual propaganda of space at Versailles. Implicitly, they understood that only a room of extraordinary length, like the Hall of Mirrors, was adequate to document the many military triumphs of the Sun King, and that only the visual language of classical allegory was elevated enough for a king to attain god-like stature. The decision to decorate a huge boardroom with a visual eulogy of the Law system would have been inconceivable without the precedent set by Louis XIV’s use of large-scale architecture and self-referential art to elevate his authority.

We argue that the grandiose scale and classical iconography of the Salle du Mississippi ceiling cut two ways. At first perhaps conceived as an echo of Versailles in its glorification of power, Pellegrini’s work ultimately served as a painful reminder of the financial collapse of Law’s system and its major proponents. Like Jansenism, the rhetoric of the Pellegrini ceiling turned inadvertently into an oppositional force to royal power, which presumably motivated the ceiling’s eventual destruction.

This “flipping” of the painting’s intended message is evident in popular satires appropriating and debunking its language of allegorical self-aggrandizement. These parodies emerged prominently in the graphic arts, reaching their foremost expression in the prints gathered in Het groote Tafereel der dwaasheid (The Great Mirror of Folly), which appeared in the Netherlands within a year of the ceiling’s completion.[3] The Great Mirror of Folly, also known as the Tafereel, not only ridiculed Law and the French monarchy, but also mocked the allegorical language of high and therefore “official” art itself.

In this article we explore the context and meaning behind Pellegrini’s painting, using an eighteenth-century description to uncover the connection between Law’s ideas about commerce and the ceiling’s iconography. Crucially, the painting responded to both the political tensions of the time and the necessity to legitimate Law’s novel scheme in the context of prevailing decorative norms and precedents of the French court. We consider evidence that parts of the painting extended beyond stock allegorical themes and figures and may have alluded to plans by Law to develop France’s commercial “infrastructure,” including the further expansion of the larger architectural complex within which the Salle du Mississippi was contained. In the hands of Pellegrini, the newly emerging rococo style captured the spirit of innovation and the geo-political opportunities on which the Mississippi scheme depended. Finally, we examine specific prints in the Tafereel, which critique the monarchy and its tradition of self-aggrandizement through art. The contextualization of these two radically different types of artworks opens up new perspectives on the problem of absolutism and global trade. They constitute both thesis and anti-thesis of the legitimacy of monarchic power and of the iconography used to solidify it.

Context and Precedent

Pellegrini painted the Salle du Mississippi ceiling during a turbulent political and economic period in France: the Regency of Phillipe II, Duke of Orléans, which followed the death of Louis XIV in 1715. In commissioning the ceiling, Law and the regent followed Louis XIV’s example of using sumptuous, self-aggrandizing decorative art for promotional purposes. In this respect, the commission and design of the work mimics the decorative program of Versailles from the 1660s, executed under the powerful partnership of court painter Charles Le Brun and royal advisor Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Colbert served both as Louis XIV’s minister of finance and his superintendent of royal buildings. In the latter role he played an important part in the program of Versailles. Le Brun was the Sun King’s favorite artist. In 1648 he co-founded the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, whose designated vice-protector became Colbert in 1661.[4] Le Brun’s painting in Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors, Order Restored to the Kingdom’s Finances (Fig. 3), depicts a key moment in Colbert’s rise to power: his exposition of France’s corrupt tax system and denouncement of Nicolas Fouquet, the king’s superintendent of finances.[5] The painting shows Minerva banishing financiers personified by harpies, while the king, in Roman military dress, hands the keys to the treasury to a female figure holding a (presumably proper) account book. In Le Brun’s painting, the king triumphs in a battle over money and re-establishes a just financial order.

The Le Brun-Colbert collaboration provided a particularly useful precedent for Law and the regent, because the centerpiece of both Colbert’s and Law’s vision was the reduction of royal debt and the creation of overseas trading companies to compete with the Netherlands, Britain, and Spain for global commercial hegemony. Law and the regent no doubt recognized that the vast decorative space of the Salle du Mississippi could be interpreted by the French nobility in the context of the Hall of Mirrors and Colbert’s economic and architectural legacy of fifty years earlier.

Nevertheless, despite clear parallels, one should not underestimate the fundamentally different mentalities separating the “grand siècle” of Louis XIV from the eight short years of the Regency, which were swept by the winds of change. The last years of Louis XIV’s rule were marked by the Sun King’s protracted health problems, his morose mind set, and increasing piety, as well as a series of wars France started and lost. These wars eventually led to the deterioration of public finances and the explosion of public debt that made the meteoric rise of John Law a few years later possible. When the king finally died, his demise was secretly celebrated as a relief by the aristocracy, who now flocked back from Versailles to Paris. The regent himself, ruling from the Palais Royal in the heart of the city during Louis XV’s minority, became the very embodiment of the era’s hunger for novelty, assertion of individuality, experiments of all sorts, and indulgence in sensual pleasures. Gone were the days when the government demanded self-sacrifice for a higher good – that of the state and the king – as the foremost duty of its servants and citizens. This turn away from austerity towards sensuality was embodied in the new rococo style, which was characterized by a delight in ornamental, multi-media interiors and paintings rendered in a loose, fluid style and a light pastel palette.[6] In this context, the building plan for the Banque Royale can be viewed as a physical manifestation of France’s new political and economic quest for progress. The Duke of Orléans and Law created a new, modern, and national institution: a royal bank on par with rivals in Britain and the Netherlands. In February 1720, they merged it with the Mississippi Company to create something even more ambitious. The Banque Royale boardroom celebrated and elevated this accomplishment.

John Law’s scheme of re-imagining the French state as a monolithic commercial enterprise, which nevertheless was owned by citizens as investors, was a radical innovation that fit in perfectly with the spirit of the Regency and the rococo. It was both an extension of Colbert’s mercantilist vision and a rejection of the stifling conventionality and control of the preceding “grand siècle.” For the regent and his financier, it was essential to create a familiar cultural context for a radical political and economic plan. This plan had to harness the ideas of both continuity and novelty. It had to reassure members of the royal court that their lives, arts, and values would be maintained even as the state shifted focus from militarism to commerce. It had to embody the idea of the “system” in its visual and spatial language.

The Pellegrini Ceiling

The ceiling was the centerpiece of Law’s ambitious architectural program to create a grand headquarters for the Banque Royal and the Mississippi Company. To that end, he managed to acquire the buildings comprising the Palais Mazarin, the former Paris residence of the famous cardinal.[7] One of these structures, the hôtel de Nevers featured a series of galleries that extended along the rue de Richelieu. The hôtel’s three galleries were joined to create one large hall. This architectural core became the Salle du Mississippi, the bank’s boardroom. As such, it was decorated for the benefit of the governors and major shareholders of the institution, and, of course, for the regent himself.

The commission for the painting came about during Pellegrini’s journey from London to Venice in 1719. He stopped in Paris in November and was entertained by the financier and art collector Pierre Crozat, a devotee of Venetian painting and an advisor to the regent on his art possessions. Crozat introduced Pellegrini to the regent and may have personally championed the Venetian for the ceiling commission.[8] The choice proved to be controversial. The French painter François Lemoyne was convinced that the commission for the Salle du Mississippi should have gone to a French artist like himself, and not to an Italian foreigner. He proposed a competing design (Fig. 4), even though there was no formal competition.[9] Why was Pellegrini chosen over a domestic competitor? One might surmise that the choice of an internationally recognized artist, as opposed to a French academician, placed the Law plan in the broader context of Enlightenment Europe. Alternatively, the choice may have reflected Crozat’s personal taste and influence. No doubt, the selection was cleared with the regent as well. Although no contract survives, Law likely engaged Pellegrini personally to decorate the Salle du Mississippi for a sum of 100,000 livres, of which Law advanced 9,500 on signing.[10] Pellegrini returned in the spring of 1720 and completed the work in a three-month period.

The principal source for visualizing Pellegrini’s Salle du Mississippi ceiling today is an anonymous manuscript description from around the time of the room’s completion, which was later printed in François-Bernard Lépicié’s Vies des premiers peintres du roi (1752). At the center of the ceiling one would have observed:

a portrait of the king, sustained on one side by Religion, and by a Hero representing Mgr. the Regent on the other. […] Below Religion, a winged and armed Genius takes Commerce by the hand, followed by Wealth, Security, and Credit. At the feet of the Genius, a child holds a bow, symbol of Invention; toward the right, slightly below the Genius, one can see Arithmetic holding in her hands a piece of paper with calculations. She is accompanied by Industry, characterized by body armor and the sword she holds in her hand. […] Above all of these figures, at the highest point in the ceiling, Jupiter is seated in the clouds; Juno is a little bit off to the side. They send out Abundance to distribute her riches. To the left of Wealth is the River Seine embracing the Mississippi River. […] Winged Happiness floats below these rivers in the clouds, holding in her hands a flame of fire; Tranquility is next to her, holding, in a completely relaxed pose, a sheaf of wheat. On the banks of the Seine, one discovers a wagon with a team of two horses, on which workers load the merchandise discharged from the vessels arriving from Louisiana; there are also other types of vessels carrying Mississippi princes. […] Above the entryway, the Bourse is represented as a portico, grouped around which one sees the representatives of diverse nations distinguishable by their dress, as they engage together in trade.[11]

Pellegrini was one of several Venetian painters who left the Republic over the course of the eighteenth century and achieved international recognition. Working in Britain from 1708 to 1713, his commissions included interiors for landed estates of the English aristocracy. On the continent, he executed high-profile decorative interiors in Prague, Dresden, Vienna, and The Hague. Many of these were allegorical compositions for which he made preparatory sketches in ink on paper, as well as oil sketches. Few of these sketches are explicitly identified as designs for his larger works, but in the case of the Banque Royale ceiling, a handful of studies appear to approximately match Lépicié’s description of certain figural groups. Secure attribution of the sketches as preparatory to the ceiling is difficult to establish due to the ambiguity inherent in Pellegrini’s work. Valentine Toutain-Quittelier’s hypothetical reconstruction of the decorative program allows us to understand something of its complex dynamics.[12]

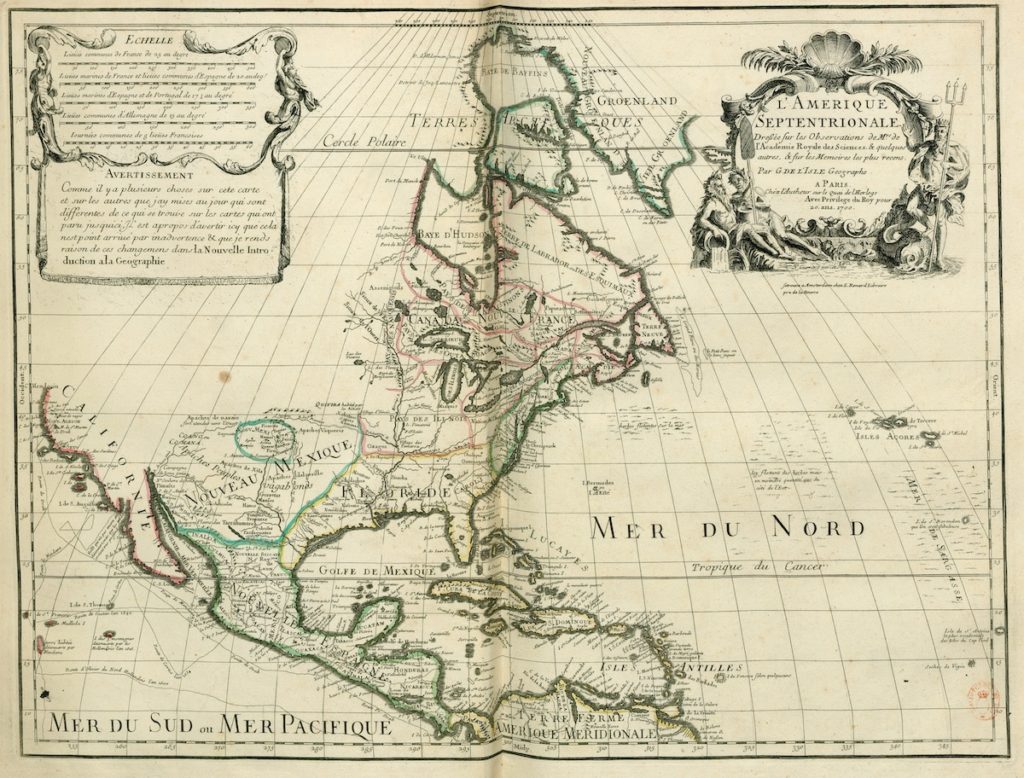

An oil sketch now in the collection of the Petit Palais in Paris (Fig. 5) is clearly identifiable as a preparatory composition for one of the main scenes that would have been visible upon entry into the Salle du Mississippi.[13] It was placed over the doorway at the opposite end of the room, perhaps as a beckoning destination. The left side of the sketch depicts two embracing figures representing the Seine and Mississippi rivers, reclining over a cornucopia representing the presumably fertile result of their union. The river gods resemble figures in the cartouche of a map of North America published in 1700 by royal cartographer Guillaume Delisle (Fig. 6). The right side of the oil sketch depicts a dockside scene: a ship and a cart matching the description of the wagon team and discharging vessels.

The sketch presents us with a well-established topology. The edges of the composition create the illusion of a vast space beyond the horizon. The mast of a ship is low in the distance. The horses pull a cart that is out of the frame; only the upper bodies of the toiling figures are shown. Pellegrini uses forced perspective to evoke an infinite geography extending across the Atlantic to America—an effect that would have been enhanced by the painting’s spatial placement vis-à-vis a viewer walking into the room and seeing the image from a distance. France, and perhaps the Mississippi Company itself, become the nexus to which the world pays tribute.

A high-masted, ocean-going ship in the background suggests that the setting is a port on the Seine, not Paris itself. In 1720, goods entered Paris via smaller riverine vessels loaded at the ports of Le Havre or Rouen. Of these, the more likely setting is Rouen, which lies at the limit of the portion of the Seine navigable by ocean-going ships. Furthermore, Law had a special interest in Rouen. According to published accounts in London and Amsterdam, the financier planned to develop Rouen into “…the greatest Staple [commercial port] in the Universe.”[14] Law’s vision for the city included an embankment, a bridge, and a zone dedicated to industry. While the scene painted by Pellegrini may be simply a general representation of a port, it is conceivable that Law discussed with the artist his ambitions for Rouen. Pellegrini and his family were houseguests of Law during the course of the commission.[15] One can imagine their conversation turning to other issues on Law’s mind at the time. The decorated stern of the ship in the oil sketch might have been inspired by talk of the two massive, armed merchant ships (the Lys and the Bourbon) that the Mississippi Company had recently commissioned for use in the India trade. Company dominance in maritime commerce was still then only a dream; in reality, its ships, in the spring of 1720, were mostly engaged in transporting prisoners, colonists, and enslaved Africans to settle the fledgling Louisiana colony.[16]

The artist’s palette in the Petit Palais sketch (Fig. 5) consists of warm earth tones, which contrast with the blue sky. Bright highlights in red, white, and gold add visual interest to the otherwise placid composition. In typical rococo fashion, neither the sketch nor the ceiling have a central focus. Because it is a sketch, it is difficult to know whether the finished painting would have shared the drawing’s fluidity and lack of detail. Pellegrini’s allegorical figures are barely identifiable. The harbor scene’s purpose is more to establish a rhythm or a mood, rather than to describe any real setting or place. Toutain-Quittelier notes that the lack of clarity and distinction among the allegorical figures motivated contemporary criticism of the Pellegrini ceiling.[17]

No sketch for the scene above the entrance to the grand boardroom has yet been identified. This absence is unfortunate because such a work may have depicted what Law believed was the future strength of the nation. This detail would have featured a bourse—an exchange in which traders from many nations engaged in commerce. The building was represented as a portico, an architectural feature of Europe’s early bourses.[18] As with the port scene, the bourse scenery would not have pictured what existed in the past or present, but rather what could be in the future.

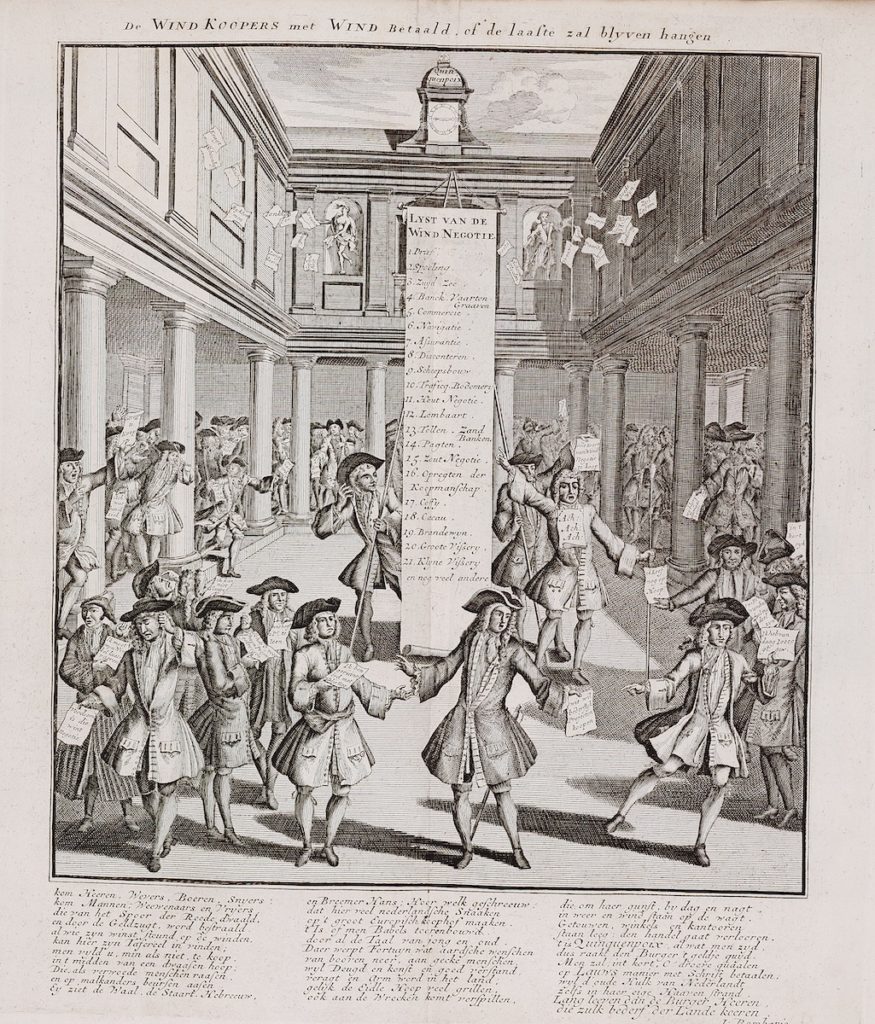

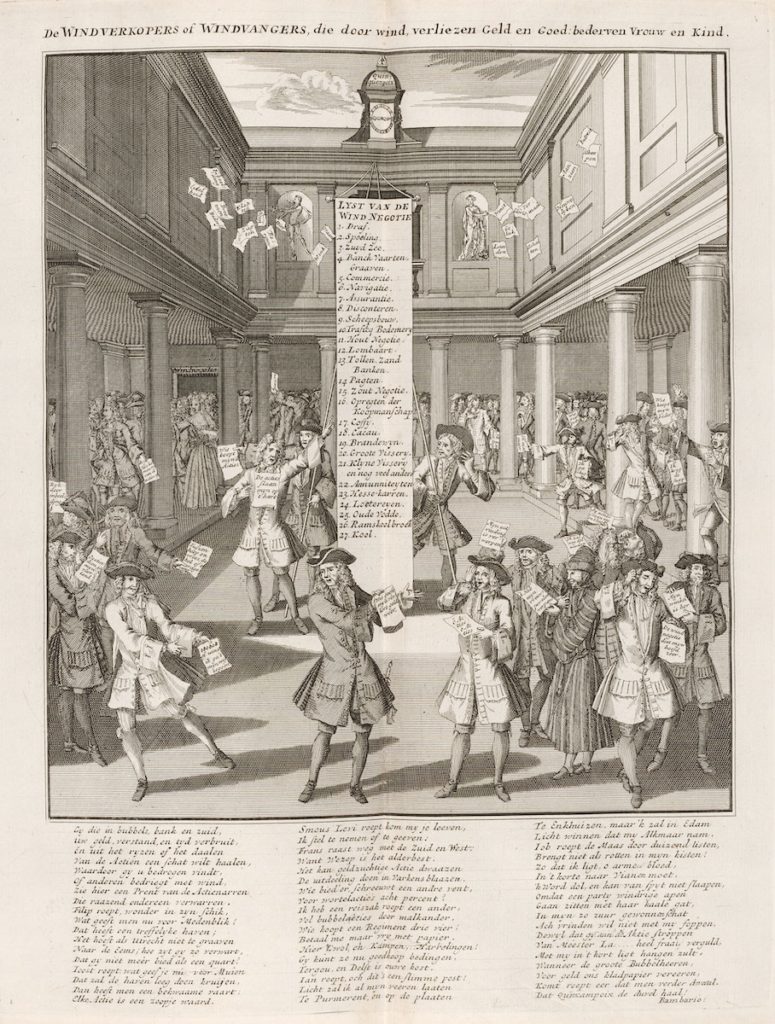

Paris did not have a formal stock exchange in 1720, but some European cities did, including London, Amsterdam, and Antwerp. All of these foreign buildings featured a layout consisting of porticos surrounding an open court.[19] Two Tafereel prints depict the porticoed bourse at Amsterdam (Figs. 7 and 8). Their prominence in the volume suggests that stock exchanges had become an important new nexus of human activity, where speculators traded scraps of paper among themselves, dreaming of profits from the myriad of schemes listed in the center of the image. While the Tafereel prints satirized the role of the exchange as a hotbed of folly, they nevertheless reflected the fact that, with the rise of investment and speculation, exchanges had become necessary civic institutions. They may have been objects of derision to Tafereel artists, but they were, for better or worse, the locus of a new wave of financialization of European economies.

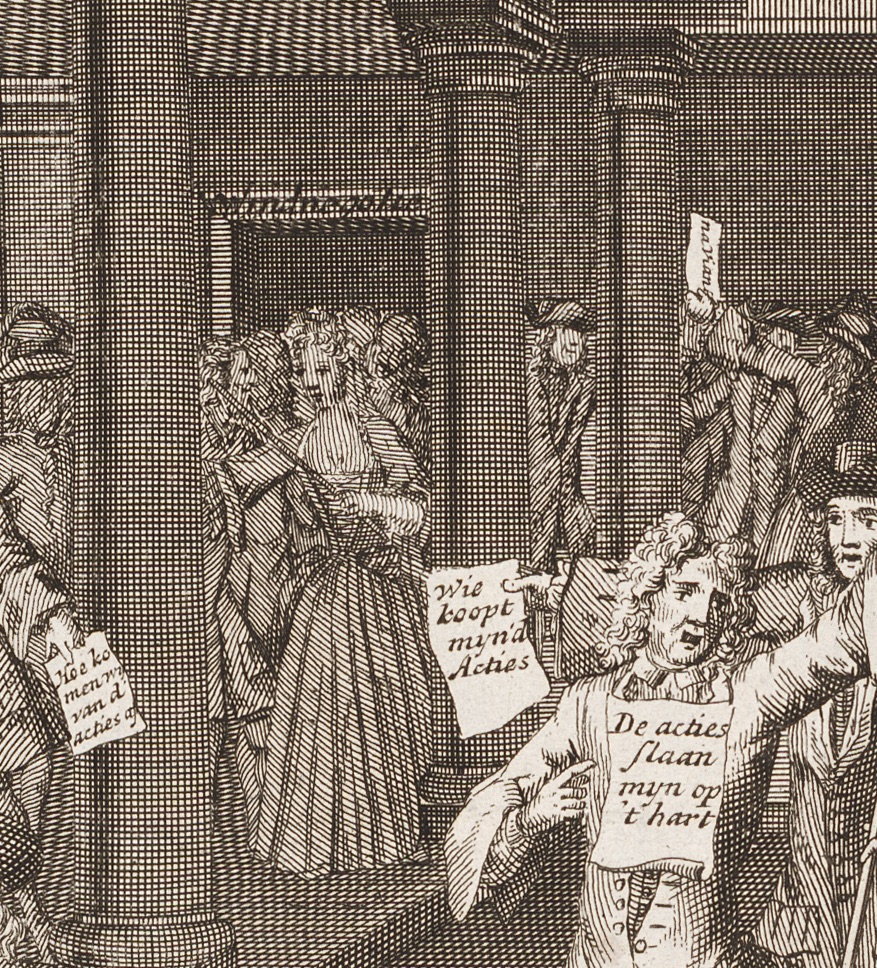

Interestingly, Fig. 8 is a mirror image of Fig. 7 and differs in an important detail. In the background of the former (Fig. 9), a woman enters the marketplace through a door marked windhandel, or “wind trade,” a pejorative term in the Tafereel for speculation. The figure may have been intended to emphasize (and criticize) the new role that the stock trade played in female empowerment. While contemporary critics mocked female participation as one more piece of evidence for finance becoming a socially subversive influence, Ann Carlos notes that stock investing in the eighteenth century opened new opportunities for women to manage their own economic affairs.[20] The conscious choice to add (or subtract) a female figure from the market scene is evidence that, by 1720, the bourse was regarded as an agent of social change, in a way we now would understand as progress.

By 1720, Pellegrini likely was familiar with the architecture of Europe’s major bourses, so the porticoed exchange may have looked something like the Tafereel prints. He had executed commissions in Britain and the Low Countries before his arrival in Paris, and passed through Antwerp in 1716.[21] Shares in the Mississippi Company traded informally in two places in Paris by 1720: in the chaotic, narrow rue Quincampoix (Fig. 10) and in the garden of the hôtel de Soissons, neither of which appeared to provide a long-term solution to the frenzied and growing demand for a public financial marketplace.

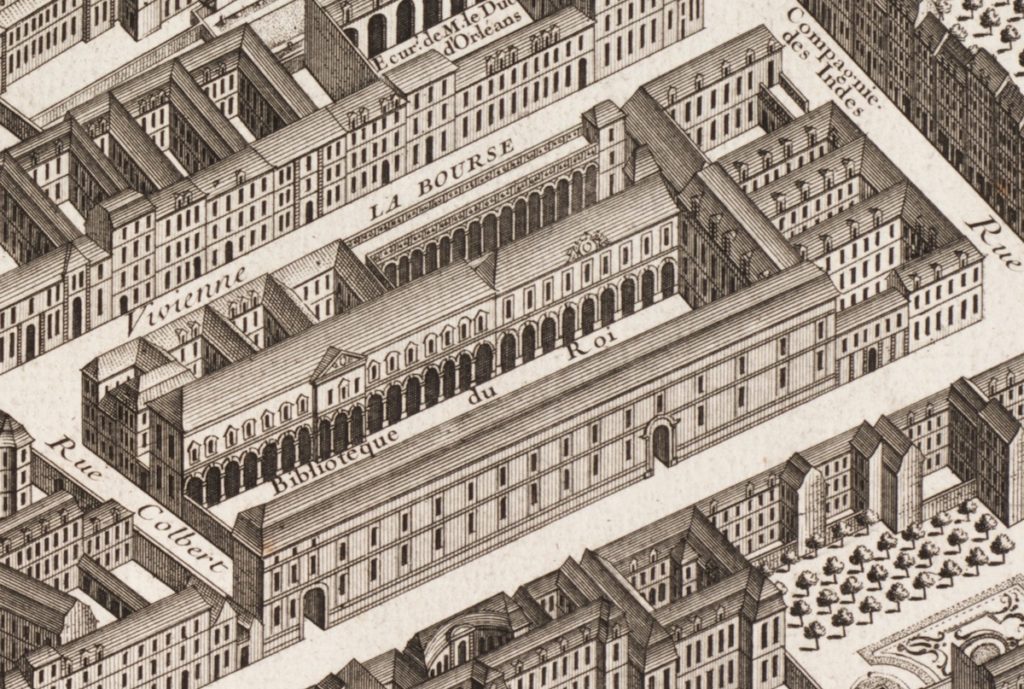

One interpretation of Pellegrini’s lost bourse scene is that, like his plans to transform Rouen into a world-class commercial port, Law had visions of turning the Palais Mazarin into an international exchange to rival Amsterdam and London. The hôtel de Nevers housing the Salle du Mississippi was only part of Law’s property acquisitions in the city block occupied by the Palais Mazarin. Biographer James Buchan cites evidence that Law acquired adjoining properties along the rue Vivienne from Jean-Baptiste Colbert’s son, Louis, with a plan to construct “an arcaded stock exchange.”[22]

The peaceful intermingling of peoples of all nations in the bourse scene is a counterpoint to Versailles’ militaristic portraits of Louis XIV as he celebrates his triumphs over other nations. The many allegorical spirits named in the Lépicié description give a sense of the positive, progressive tone that Pellegrini sought to evoke. These genii include commerce, wealth, trust, credit, invention, arithmetic, industry, magnanimity, abundance, felicity, tranquility, science, navigation, history, time, truthfulness, vigilance, eloquence, utility, and justice. He also included a few vices: gossip, ignorance, envy, laziness, misery, and troubles, all of which, presumably, stood in the way of progress. Law’s new “system” was thus characterized as an enlightened, magnanimous program for shared peace and abundance through trade, a theme that enjoyed the peak of its artistic popularity with Benjamin West’s Penn’s Treaty with the Indians from 1771-1772 (Fig. 11).

Law himself liked to contrast military with commercial power. In an open letter from May 18, 1720, he defended his system. In this missive, he argued for peaceful commerce as a source of national power, and a large bourse as a means to attain this goal:

And what should we not expect from the power of the nation? I am speaking less here of the power of arms to defend against enemy attacks, than of the power of commerce, in which those who would naturally be our enemies will be obliged to take interest. A weak merchant, whom jealousy would lead to destroy the strong merchant, soon perceives that his fortune consists in attaching himself to him and strengthening him still more. It has long been known that in matters of trading and banking, the largest bourse attracts everything, and leaves only commissions to others.[23]

Written at a time when Pellegrini was painting the ceiling and while Law and the artist were in frequent contact, the letter makes it plausible that the scene over the entrance to the room reflected Law’s thinking about the importance to France of creating this “largest bourse.” Driven by boundless ambitions, Law’s plans may have reached further to include a plan to construct this large bourse in the Palais Mazarin itself. If so, he was no longer the minister of finance when it came to fruition. On September 24, 1724 a royal decree officially established the first Bourse de Paris at the hôtel de Nevers (Fig. 12).

In order to identify where Law’s thought and the imagery of Pellegrini’s ceiling intersect, let us apply a short quantitative exercise to both Lépicié’s description of the artwork and the complete writings of Law. Eight of the 64 named elements in the Lépicié description are mentioned on more than 100 pages in Harsin’s three-volume set of the 1934 edition of Law’s Œuvres complètes: France, commerce, time (temps), merchandise (marchandises), provinces, justice, history (histoire), and industry (industrie). Of these, Pellegrini painted allegorical figures representing commerce, time, justice, history, and industry. Interestingly, the term “bourse” appears only six times in Law’s writings. Obviously, the themes that inspired Pellegrini’s decoration were not a product of artistic fancy but figured at the forefront of his patron’s mind.

Commercial scenes graced the two ends of the Salle du Mississippi. However, much of the remainder of Pellegrini’s ceiling depicted the power structure that legitimated the system. The future king Louis XV is centrally represented as a young Apollo, in the tradition of his father—and thus representing continuity of divine right. Lépicié also prominently highlights the importance of the regent, shown as a hero in service to religion, supporting and guiding the young prince. Toutain-Quittelier suggests that the central place occupied by the regent in the painting—and not the bursting of the Mississippi Bubble—may ultimately have precipitated its destruction.[24] With the crowning of Louis XV in 1722, and the formal transfer of power in the following year, a painting celebrating the regent’s authority may no longer have been politically desirable.

The exact date of the Banque Royale ceiling’s demolition, in any case, remains uncertain. Recent research suggests it was removed sometime between 1725 and 1728 to make room for the royal library, today’s Bibliothèque nationale, on the rue de Richelieu.[25] There is no evidence that the vast canvases making up the decorations were preserved. Nevertheless, despite its destruction, the ceiling remains a tribute to one of the most audacious experiments in the history of governance and the history of finance.

The Law System

Finance played an important role in progressive Enlightenment thought. Spurred, on the one hand, by costly European wars that placed governments in debt, and, on the other, by the rapid expansion of maritime trade, financial innovation became an increasingly important co-factor in the economies of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Europe. Some of these novelties were state-sponsored, while others posed threats to statist economic control. Perhaps most significantly, they unlocked the power of individual investors.

For example, in 1694, the Bank of England, a publicly traded company, was granted exclusive rights to issue paper money in exchange for a massive loan to the war-weakened English government. In contrast to this state monolith, London, in the decades around 1700, became a hotbed for experimentation with the corporate form. Dozens of speculative companies were launched to finance a myriad of innovative products, processes, and services, many of which failed, but some of which did succeed. While the Bank of England effectively served as a financial organ of government, “bubble” companies trading in London’s Exchange Alley diverted speculative capital from state-sponsored enterprises to the pockets and dreams of independent entrepreneurs, stimulating the private sector of the British economy.[26]

The Law system fell squarely in the state-sponsored camp. Modelled in part on the Bank of England, the financier’s scheme was even more ambitious—beginning with a bank but growing into an all-encompassing enterprise. Likely drawing on other imaginative proposals current in France at the time, it de facto constituted a Hobbesian contract in which citizens ceded authority to a profit-seeking state in exchange for a share of its spoils.[27]

Antoin Murphy’s intellectual biography of Law identifies him as an important monetary theorist: an Enlightenment thinker who understood that the European economy at the beginning of the eighteenth century was hampered by the twin problems of excessive state debt and scarcity of money.[28] The former weakened the state, and the latter restricted productive economic activity. Before his French adventure, Law approached several European nations with economic plans for banks to issue paper money. After these unsuccessful attempts, Law approached the court of Louis XIV with a proposal that began as a plan for a state bank, but quickly grew into a complex scheme involving the merging into one vast firm of virtually all of France’s revenue sources, including its international trading companies, tax farms, and commodity monopolies.

Law’s ideas fell on fertile ground. By the second decade of the eighteenth century, Louis XIV’s wars had financially exhausted France. With the king’s death in 1715, the Duke of Orléans consolidated control as regent to the young Louis XV. His step into power necessitated concessions to the Parlement of Paris for rights of remonstrance—the right to review and challenge the legitimacy of laws issued by the crown which had been previously curtailed by Louis XIV.[29] The regent quickly embraced both Law’s financial plan for a bank and his grander vision for consolidating France’s licensed trade monopolies (together with the bank) into a single entity, but, as we will discuss, the Parlement right of remonstrance presented a recurring problem.

Law’s Banque générale, at first a private bank, began operations under the patronage of the regent in 1716. It issued paper banknotes and discounted bills of exchange at rates that undercut those of the established French financiers—the same sector represented in Le Brun’s Versailles painting. The bank’s operations were both profitable for Law and beneficial to French commerce. In the summer of 1717, Law launched the Compagnie d’Occident (Company of the West), which assumed the languishing Louisiana concession of Antoine Crozat (the wealthier brother of Pierre) for 25 years with the promise to colonize and develop profitable plantations in return for exclusive trade rights and broader military and diplomatic powers.

Later called the Compagnie des Indes, the entity’s distinctive feature was financing. State-sponsored overseas trading companies were nothing new (the Dutch East India Company, for example, was founded in 1602), but the use of them to re-finance government debt was an extraordinary innovation. Subscriptions for shares in the new company were open to the general public as well as to foreign investors. At 500 livres per share, they were not cheap, but the price was payable in billets d’État, which were French state promissory notes that were deeply discounted by the market due to uncertainty about government creditworthiness. In company hands, these old notes were replaced by new state debt issue, bearing an interest rate of 4%.

Crucially, the shares had something the billets d’État did not: the potential to participate in the profits of New World trade. Since his flight from London in 1694, Law had made a living running gambling operations for the high society of continental Europe. Perhaps this experience taught him something essential about human nature. By offering shares to the moneyed classes with a taste for risk and speculation, he harnessed human exuberance in the service of financing his grand scheme.

Law’s radical innovation did not go unchallenged. The Parlement of Paris vigorously resisted his plan through remonstrance against royal edicts. John Hurt argues that the confrontation over Law’s plan brought the Parlement to the brink of revolt, and that the regent only managed to reassert royal authority through a clever maneuver, a lit de justice, in 1718.[30] A royal decree of June 17, 1719 was a particularly important step in realizing the larger designs of the Law plan. It effectively overrode the Parlement’s objections and merged the Compagnie des Indes Orientales (East India Company), the Compagnie de la Chine (China Company), and the Compagnie du Sénégal (Senegal Company) into the Compagnie d’Occident, which was renamed the Compagnie des Indes, commonly referred to as the Mississippi Company. The inclusion of the Senegal Company made it clear that trans-Atlantic trade in human cargo was a key element of Law’s plan. Indeed, one of the conditions of the company’s patent was a quota of thousands of African enslaved laborers, as well as European colonists, to be brought to Louisiana. Although the Parlement was skeptical of the merger, investors and speculators were enthusiastic. Shares in the Mississippi Company were quoted at 635 livres on the 17th of June. A week later, they traded at 750, and, by the end of July 1719, they had risen to 2,000.[31] The bubble was now underway.

The conflict between the Parlement and the regent, however, was far from settled despite the lit du justice. Much of the 1719 proclamation addresses the Parlement’s defiance of the mergers and threatens those who resist the king’s will. Concerns over political conflict were evidently not trivial. Fearing for his life, Law was in hiding from the Parlement when the edict stipulating the mergers was debated.[32] Finally, in 1720, the giant monopoly was merged with the bank itself.

The royal proclamation of June 17, 1719 also provides important context for the Pellegrini ceiling. The artwork can be interpreted as a defiant re-assertion of the regent’s authority and an illustration of the larger purposes and benefits of the consolidation of the trading companies into a single firm. One key passage of the decree affirms: “We unite in one single company a commercial enterprise that extends to the four corners of the world [our emphasis]. This company contains by itself all that is needed to sustain these different commercial activities. It will bring to our kingdom things necessary, useful, and convenient. It will send our surplus production abroad.”[33] Pellegrini’s ceiling thus illustrates both the company’s geographical extent and its central purpose of international trade.

The device of the four corners of the world was not only central to Law’s conception of a single, boundless enterprise in the service of the French state and people, but it also inspired other rulers and artists of the eighteenth century (including Pellegrini’s sister-in-law, Rosalba Carriera, who accompanied him to Paris). The Salle du Mississippi painting fits neatly into the rococo tradition of illusionistic ceilings depicting the geographical extension of political authority, the most famous of which is Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s Apollo and the Four Continents from 1750-1752, which graces the ceiling of the Würzburg Residenz (Fig. 13).[34] As in the Salle du Mississippi, the key visual content of the Würzburg ceiling is relegated to the margins, each one of which is assigned a figurative group allegorically representing one of the four continents. Tiepolo’s primary interest was with the creation of visually powerful, exotic vignettes, while catering to the megalomania of his patron, the Prince-Bishop Karl Philipp von Greiffenklau.

In sum, Pellegrini’s representation of the Law system centered on revealing the expected future benefits of a bank and the reach of the integrated global trading company of which it was a part. His depictions of maritime trade and international marketplaces highlighted not only the firm’s potential payoff to shareholders, but also the higher purpose of stimulating the French economy. The central allegorical representation of king and regent placed this plan in a political context, and the multitude of winged virtues and vices assured viewers that the system was congruent with the ethical framework of the time.

The system had begun to falter even as Pellegrini was finishing the ceiling in the spring of 1720. Part of Law’s promotional scheme was to allow investors to purchase shares on credit. This was fine when prices went up, but share prices declined in March, prompting liquidations, flight to cash, and then to coin. This development forced the bank to suspend specie payments and peg Mississippi share prices at 9,000 livres. The artificial support could not be sustained, and Law attempted a controlled deflation in May that ultimately drove prices down by a factor of 60% by October. By the end of the year, Law had fled France. The system’s brilliance—turning government debt into a public company—was also its weakness. Prices respond to investor sentiment. Law had investors’ support when they were making paper profits. He lost their support when prices dropped. Not even a magnificent rococo ceiling could appease the market’s judgment.

Critique of Triumphant Allegories in The Great Mirror of Folly

There exists, of course, one major alternative visual document dealing with finance and speculation contemporary with John Law and his Mississippi Company. The Great Mirror of Folly was printed in Amsterdam in 1720 to memorialize and critique the popular speculative frenzies that caused stock markets in France, Britain, and the Netherlands to rise spectacularly and then crash throughout that year. On the one hand, the satirical prints, plays, and poems in the Tafereel attributed the bubbles to human mental and moral frailty. On the other hand, Tafereel artists turned their attention to the very system that first enabled the speculation. Their focus was not only on Law and his company, but also on his royal sponsors and their self-serving monuments and allegories.

Several of the prints in the Tafereel mock royal authority and its artistic expression, turning the language of allegory back on its elite audiences. After all, the magnificent rococo ceilings of Pellegrini and the Tiepolos were created to elevate rulers above their subjects. The powerful who commissioned them were portrayed as classical gods lifted into the clouds—closer to the angels than to the territory they ruled. These self-aggrandizing ceremonial spaces were ripe for covert ridicule.

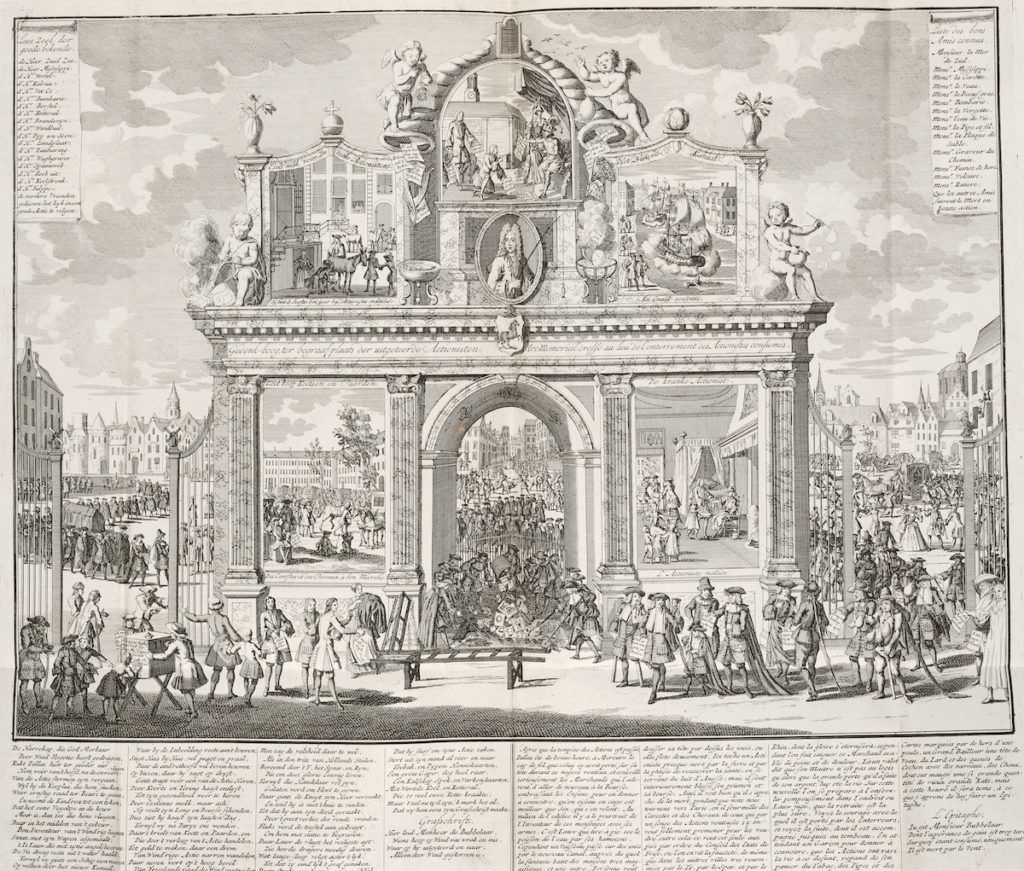

For example, the plate entitled Memorial Arch Erected at the Burial Place of the Ruined Share Traders (Gedenk-boog, ter begraaf-plaats der uitgeteerde actionisten; Fig. 14) pictures an elaborate triumphal arch in the heart of Paris, with cornucopias spewing out worthless paper instead of riches. The setting likely references Parisian triumphal arches erected at Porte Saint-Denis and Porte Saint-Martin in 1672 for Louis XIV’s military victories in the Rhineland and the Franche-Comté, along with the tradition in which they were created. Although the picture is rich in comic detail, the pompous French public edifice is the artist’s principal joke. Law is the new hero of a modern financial age, accompanied by rambunctious genii who blow bubbles, start fires, and generally create mayhem. All this mischief is embedded in an outsized, expansive construction to glorify Law and his system.

Other prints mock the notion of global hegemony. The Tafereel is full of images of globes: some as burdens, some as emblems of fascination, some conflated with religious orbs.[35] Artists had used globes as symbols for global domination at least since the sixteenth century. Giorgio Vasari, for example, cites in his Lives a portrait of the emperor Charles V, in which Parmigianino painted “Fame crowning [the emperor] with laurel, and a boy in the form of a little Hercules offering him a globe of the world, giving him, as it were, the dominion over it.”[36] One particularly powerful image from the Tafereel seems to turn the theme of global commercial hegemony inside out. In The World of Scrap Paper Is Turned by Fire into Ashes (Des Kladpapieren Waerelds vuur in as verkeerd; Fig. 15), a pair of putti preside over a conflagration. They are not harbingers of a benevolent god, but instead come to set a small, paper globe aflame. Gathered around the fire are men and women, rich and poor, clergy, and royalty. The world in the picture is not a vast domain with France or the Holy Roman Empire at its center, drawing in riches from all quarters. Rather, it is a small, fragile orb about to be reduced to ash, its worshippers on the verge of abandoning their homes, fields, cities, and kingdom. The king and queen at the center of the image are no less venal or avaricious than their subjects. They are not ascending into heaven, ruling from above, or dispatching genii to oversee commerce. The text below the image clearly blames the king for this sad state of affairs: “Woe to the country whose king is … ”.[37] The ellipsis holds the place of a missing appellation for the king, supplied in the verse below it, “kaallissen,” a Dutch colloquial term for a bum.

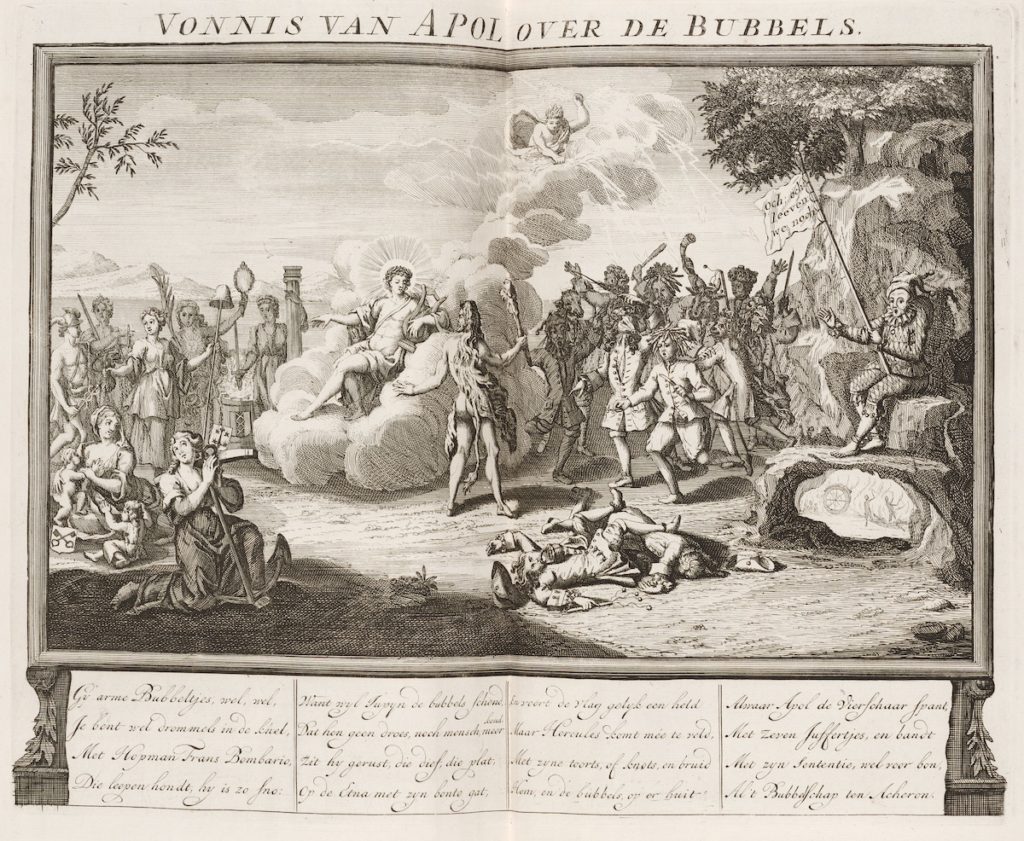

Toutain-Quittelier identifies another image that could be interpreted as an iconoclastic critique of allegory.[38] Apollo’s Judgment on Shareholders (Vonnis van Apol Over de Bubbels; Fig. 16) depicts Apollo perched on a fallen cloud where he joins a pantheon of gods: Mercury, Venus, Justice, and Minerva, who stand with personifications of the few Dutch cities left untouched by the windhandel: Amsterdam, Leiden, and Haarlem. The gods and cities cower before a savage crowd of shareholders cheered forward by a malevolent Harlequin. Hercules stands protectively between the men and the gods. He has knocked down two of the attackers, but the outcome of the battle between gods and men—fought on the ground, not in the air—appears to be still in doubt.

Conclusion

Until now, the prints of the Tafereel and the iconography of rococo ceiling painting have been studied separately, but in our view they should be understood as two sides of the same coin.[39] Enlightenment thought is often portrayed as moving in opposition to eighteenth-century structures of power, whether ecclesiastic or royal. The allegorical imagery of the Salle du Mississippi appears to be an exception to this rule. Pellegrini was challenged to visualize a radical redefinition of the French state while maintaining continuity through traditional allegorical artifice and the glorification of royal authority. If John Law had opened the French economy to widespread public participation, this expansion was only possible within the framework of monarchical absolutism—and then just barely. Issuing shares in the Mississippi Company and promoting their speculative possibilities allowed Law to raise the capital required to realize his notion of a monolithic trading company, if only for a few short months before its downfall. The prosperity of a global business empire required participation of the many, while paying service to the vanity of the few. However, in so doing it made promises and raised widespread public expectations which it ultimately failed to fulfill.

The decorations by Pellegrini and his followers were well aligned with the political powers of the age. To avoid controversial content, suave allegorical figures became the place holders of vulgar money in all its forms, including paper securities. Not coincidentally, the explicit depiction of currency and stock certificates, combined with allegorical figures turned into satire, is a hallmark of the Tafereel. It helps to understand the social conventions of the difference in artistic media to make sense of this dichotomy. As the historian of graphic art, Linda C. Hults, so astutely observed:

An understanding of the history of prints as opposed to paintings also forces us to reevaluate our notions of stylistic innovation, national preeminence, and the relative importance of subject matter. […] The print tends to be linked “horizontally” to popular and functional art forms such as advertising, political cartooning, reproduction of other works of art, or illustration, rather than to disassociate itself from these art forms, “vertically,” as paintings have done.[40]

In this scheme, Pellegrini’s ceiling and the works of other artists of the eighteenth century who referenced European geographical and economic hegemony unmistakably move on the “vertical” axis, while the Tafereel moves on the “horizontal” axis. While they appear to operate independently, they share, in fact, a common intent to portray the potentially disruptive technology of financial innovation.

It is tempting to construe the Tafereel as a visual document of the Enlightenment, but such a reading would generate mostly misleading conclusions. The Tafereel is foremost a thoroughbred product of what Hults calls the “graphic satirical tradition.”[41] As such, it has a lot of “missing” information to disclose about the age of John Law. It tells us of all those things that were left unsaid by the panels from Pellegrini’s ceiling. In hindsight, the eloquent silence is better understood for what it really was from the perspective of the twenty-first century than from that of the eighteenth: an admission of the plethora of weaknesses built into Law’s “system” from the start.

William N. Goetzmann is the Edwin J. Beinecke Professor of Finance and Management Studies at Yale University

Darius A. Spieth is the San Diego Alumni Association Chapter Alumni Professor of Art History at Louisiana State University

Translations by authors, unless noted otherwise.

[1] Louis Marin, “The Body-of-Power and Incarnation at Port Royal and in Pascal; or, Of the Figurability of the Political Absolute,” trans. Martha M. Houle, in Fragments for a History of the Human Body, ed. Michel Feher, 3 vols. (New York: Zone Books/MIT Press), 3:421-422.

[2] James Buchan, Frozen Desire: The Meaning of Money (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997), 130.

[3] The Great Mirror of Folly: Finance, Culture, and the Crash of 1720, eds. William N. Goetzmann, Catherine Labio, K. Geert Rouwenhorst, and Timothy Young (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013) is a multi-disciplinary study examining the authors, artists, time, and place of publication of the Tafereel.

[4] Christian Michel, The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture: The Birth of the French School, 1648–1793 (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2018), 29.

[5] Albert Borowitz, “Fouquet’s Trial in the Letters of Madame de Sevigne,” Legal Studies Forum 29:2 (2005), 789-800.

[6] See, for instance, Katie Scott, The Rococo Interior: Decoration and Social Spaces in Early Eighteenth-Century Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

[7] Bounded by the rue Neuve-des-Petits-Champs, on the south; the rue Vivienne, on the east; and the rue de Richelieu, on the west.

[8] Franca Zava Bocazzi, “Pellegrini ‘privato’ nell’ epistolario di Rosalba Carriera,” in Antonio Pellegrini: Il Maestro Veneto del Rococo alle corti d’Europa, ed. Alessandro Bettagno (Venice: Marsilio, 1998), 80.

[9] Jean-Luc Bordeaux, François Le Moyne and His Generation, 1688-1737 (Neuilly: Arthena, 1984), 30-31; André Michel, Histoire de l’art, 8 vols. (Paris: Colin), 7/1:141-143.

[10] Toutain-Quittelier, Le Carnaval, la fortune et la folie, 199.

[11] “Description de la Peinture de la Galerie de la Banque Royale,” Bibliothèque nationale, Dépt. des manuscrits, NAF 22261, fols. 78-79, reprinted in François-Bernard Lépicié, Vies des premiers peintres du roi, depuis M. Le Brun jusqu’à présent, 2 vols. (1752; Geneva: Minkoff Reprint, 1972), 2:122-27: “…Le portrait du Roi…est soûtenu d’un côté par la Religion, & de l’autre, par un Héros qui représente M. le Régent […] Au-dessous de la Religion, on a représenté le Génie avec des ailes & un casque; il conduit par la main le Génie du Commerce suivi de la Richesse, de la Sûreté & du Crédit: aux piés du Génie, un enfant tient un arc à la main, symbole de l’Invention; à la droite, un peu au-dessous du Génie, on voit l’Arithmétique tenant dans ses mains un papier de compte; elle est accompagnée de l’Industrie qu’on a caractérisée avec un casque, & tenant une épée à la main. […] Au-dessus de toutes ces figures, & au plus haut du plafond, Jupiter est assis dans les nuées, Juno est un peu plus loin; ils envoyent l’abondance pour verser ses richesses. A la gauche de la Richesse est la riviere de Seine, qui embrasse le fleuve du Mississipi […] La Félicité avec des ailes est au-dessous de ces rivieres à travers les nuées, tenant dans ses mains des flammes de feu; la Tranquillité est à côté d’elle dans un plein repos avec des épis de bled à sa main. Sur le bord de la Seine, on découvre un chariot attelé de deux chevaux, sur lequel des chargent des marchandises qu’on débarque des vaisseaux de la Louisiane; il y a d’autres especes de bâtimens, sur un desquels on voit des Princes Mississipiens. […] Au-dessus de la porte par où l’on entre, la Bourse est représentée par un portique, autour duquel on voit diverses nations avec leurs habillemens qui négocient ensemble.” See also Pierre-Jean Mariette, Abecedario de P. J. Mariette et autres notes inédites de cet amateur sur les arts et les artistes (Archives de l’art français VIII), eds. Charles-Philippe de Chennevières-Pointel and Anatole de Montaiglon, 6 vols. (Paris: Dumoulin, 1857-1858), 4:95-98.

[12] Valentine Toutain-Quittelier, Le Carnaval, la fortune et la folie: La Rencontre de Paris et Venise à l’aube des Lumières (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2017), 212.

[13] The sketch is featured on the website of the collections of the Petit Palais: http://www.petitpalais.paris.fr/en/oeuvre/sketch-ceiling-banque-royale-unloading-goods-louisiana-banks-seine (accessed Feb. 2, 2020).

[14] James Buchan, John Law: A Scottish Adventurer of the Eighteenth Century (London: MacLehose Press, 2018), 233, quoting British and Dutch press accounts.

[15] Boccazzi, “Pellegrini ‘privato’,” 80.

[16] James D. Hardy, “The Transportation of Convicts to Colonial Louisiana,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 7:3 (1966): 207–220.

[17] Toutain-Quittelier, Le Carnaval, la fortune et la folie, 200.

[18] Donatella Calabi, “Trading Spaces in European Port Cities: The Architectural Models of Bourses, Lonjas, and Exchanges,” in The Routledge Handbook of Maritime Trade around Europe 1300-1600 (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 57-68.

[19] Calabi, “Trading Spaces,” 57-68.

[20] Ann M. Carlos, Karen McGuire and Larry Neal, “Women in the City: Financial Acumen during the South Sea Bubble,” in Women and Their Money 1700-1950, eds. Anne Laurence, Josephine Maltby and Janette Rutterford (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), 36. See also Frans De Bruyn, “Satire and Image: Bubble Publications in England and the Netherlands Compared,” in The Great Mirror of Folly, ed. Goetzmann et. al., 165 and 172 n.16.

[21] Boccazzi, “Pellegrini ‘privato’,” 80.

[22] Buchan, John Law, 235 and 459 n. 66.

[23] “Et que ne doit-on pas attendre de la puissance de la nation ? Je parle moins ici de la puissance des armes pour se défendre des attaques des ennemis, que de la puissance du commerce, auquel ceux qui seraient naturellement nos ennemis seront obligés de prendre intérêt. Un commerçant faible, que la jalousie porterait à détruire le fort commerçant, s’aperçoit bientôt que sa fortune consiste à s’attacher à lui, et le fortifier encore davantage. On sait depuis longtemps qu’en matière de négoce et de banque, la plus grosse bourse attire tout, et ne laisse aux autres que les commissions.” John Law, “Troisième lettre où l’on traite encore des constitutions et du crédit.” Cited after John Law: Oeuvres completes, ed. Paul Harsin, 3 vols. (Paris: Recueil Sirey, 1934), 3:145.

[24] Toutain-Quittelier, Le Carnaval, la fortune et la folie, 216.

[25] Toutain-Quittelier, Le Carnaval, la fortune et la folie, 214.

[26] For an overview, see William N. Goetzmann, Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 320-381.

[27] Arnaud Orain, La Politique du merveilleux: Une Autre histoire du système de Law (1695-1795) (Paris: Fayard, 2018), 18, 67.

[28] Antoin E. Murphy, John Law: Economic Theorist and Policy-Maker (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997). See also John Law, ed. Harsin, 1:24 and 3:129.

[29] Joseph H. Shennan, “The Political Role of the Parlement of Paris, 1715-23,” The Historical Journal 8:2 (1965), 179-200.

[30] John J. Hurt, “Confronting the Parlement of Paris, 1718,” in Louis XIV and the Parlements (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), 161-166.

[31] Database of prices available at https://som.yale.edu/faculty-research/our-centers-initiatives/international-center-finance/data/historical-southseasbubble (accessed August 26, 2020). For details see Rik GP Frehen, William N. Goetzmann, and K. Geert Rouwenhorst, “New Evidence on the First Financial Bubble, Journal of Financial Economics 108:3 (2013), 585-607.

[32] Murphy, John Law, 181.

[33] [Louis XV, King of France], Arrest du Conseil d’Estat du Roy concernant la réunion des Compagnies des Indes orientales et de la Chine à la Compagnie d’Occident, du 17 juin 1719 (Paris: Saugrain et Prault, 1719), 7: “D’ailleurs par ce moyen & par la jonction qui a esté faite à la Compagnie d’Occident de celle du Senegal, Nous réünissons dans une seule Compagnie un Commerce qui s’étend aux quatre Parties du monde. Cette Compagnie trouvera dans Elle-mesme toute ce qui sera necessaire pour faire ces differens Commerces; Elle apportera dans nostre Royaume les choses necessaires, utiles & commodes; Elle envoyera les superfluës à l’Etranger.”

[34] On Tiepolo’s Apollo and the Four Continents ceiling, see Filippo Pedrocco, Tiepolo: The Complete Paintings (New York: Rizzoli, 2002), 137-149, 285-289, nos. 222-229; Giambattista Tiepolo, 1696-1770, ed. Keith Christiansen, exh. cat. (New York: Abrams, 1996), 302-211; Mark Ashton, “Allegory, Fact, and Meaning in Giambattista Tiepolo’s Four Continents in Würzburg,” The Art Bulletin 60:1 (March 1978), 109-125. See also The Language of Continent Allegories in Baroque Central Europe, eds. Josef Köstlbauer, Marion Romberg, and Wolfgang Schmale (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2016), which documents the tradition of continental allegories and ceilings representing the four continents from the late sixteenth to nineteenth centuries; and Marion Romberg, “Continent Allegories in the Baroque Age – A Database,” Journal 18, Issue 5 Coordinates (Spring 2018): https://www.journal18.org/2412 (accessed July 7, 2020).

[35] See Benjamin Schmidt, “The Folly of the World: Moralism, Globalism, and the Business of Geography in the Early Enlightenment,” in The Great Mirror of Folly, eds. Goetzmann et al., 249-261, which catalogues the variety of ways that globalization is mocked in the Tafereel.

[36] Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors & Architects, trans. Gaston du C. de Vere, 10 vols. (London: MacMillan, 1912-1914), 5:251.

[37] “Wee u gy Land welks Koning een K… is.”

[38] Toutain-Quittelier, “Le Diable d’argent et la Folie. Enjeux et usages de la satire financière autour de 1720,” in L’Image railleuse: La Satire visuelle du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours, eds. Laurent Baridon, Frédérique Desbuissons, and Dominic Hardy (Paris: INHA, 2019): https://books.openedition.org/inha/7923 (accessed July 7, 2020).

[39] For a general study of the iconography of continents, see The Language of Continent Allegories, ed. Kostlbauer et al.

[40] Linda C. Hults, The Print in the Western World (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), xiv, 11.

[41] Hults, The Print in the Western World, 13.

Cite this article as: William N. Goetzmann and Darius A. Spieth, “The Banque Royale Ceiling and the Imagery of Finance in the Age of Absolutism,” Journal18 Issue 10 1720 (Fall 2020), https://www.journal18.org/5124.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.