David Pullins

A horse stands in profile against a bucolic landscape populated by two pastoral figures, a flock of sheep and a dog (Fig. 1). Visual analysis confirms the content of an eighteenth-century label once affixed to the painting’s stretcher: “The horse was recently painted by [George] Stubbs in London, the background of the picture by [Claude-Joseph] Vernet, the celebrated marine painter, and the two figures, the dog and the sheep, by [François] Boucher, Principal Painter to the King of France.”[1] The tightly knit strokes of the horse contrast with the looser blending of tones in the landscape and sky that come just short of meeting the animal’s outline, resulting in a halo that heightens the sense of this central element as a kind of cut-out affixed somewhat unconvincingly to the canvas. The most rapidly applied brushstrokes have been used to represent the human figures, sheep and dog, all cleverly folded into the landscape at a break between foreground and background, a line that is sutured further through lightly applied lichen-green paint along the crest of the hill and blades of grass that sprout between the horse’s legs.

Fig. 1. George Stubbs with later additions by Claude-Joseph Vernet and François Boucher, Hollyhock, oil on canvas, c.1765–1770. The Royal Collections Trust. Image: Royal Collections Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015.

This painting, little published and rarely on public view, is a difficult object, a curiosity that seems to have failed to satisfy the expectations or categories used by historians of French or British art. Its only in-depth study is Judy Egerton’s excellent entry written with advice from Alastair Laing in her Stubbs catalogue raisonné.[2] In this article I would like to posit that the status of this work when it was produced in the late 1760s was very much that of a curiosity as we encounter it today but that it holds a more specific and revealing historical importance.[3] It sits, I believe, at a pivotal moment between how we understand artistic authorship as a singular, consolidated entity and an earlier acceptance of multiple hands on a given work of art. It tacitly acknowledges, in a way often found uncomfortable today, continuity between painting in oil on canvas and painting on other supports – and, indeed, products of entirely other media. This is also to say that while strange or possibly an object of mondaine wit in the 1760s, this painting was only newly so, for it partook of older traditions for producing a wider spectrum of visual culture in which painters like Stubbs, Vernet and Boucher had long been active. The Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture’s transformation of painting from a mechanical to liberal art in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has been well studied. True to that institution’s biases these analyses have focused heavily on texts by encyclopédistes, academician-amateurs or critics responding to the Académie’s Salon. But how might a complicated object such as this one speak to the transformation of painting as a profession at the level of the mechanical realities of art making and bring to the fore commercial practices deliberately obfuscated in academic discourse?

I would like to begin with an extended discussion of this understudied painting, attempting to understand how it came to be and the questions that its genesis prompts. I then want to sketch three frames for understanding this painting that come at it from mechanical aspects of production, ones that were on the verge of extinction by the 1760s – at least within the category of art as defined by the Académie, its texts and most Salon critics.

“A Very Curious and Singular Picture”

Stubbs’s Hollyhock originated in 1765 or 1766 as the study of a yearling recently purchased by Frederick Saint John, 2nd viscount Bolingbroke.[4] In the absence of the artist’s collection of preparatory drawings, lost since his studio’s dispersal in 1807, oil studies and technical analysis of related works document Stubbs’s working method. When first “finished” Hollyhock was probably very similar to his studies Pangloss (c.1762; Indianapolis Museum of Art) and Eclipse (c.1769; The Royal Veterinary Hospital, London) in which the central subject of the horse was brought to a high degree of finish while the ground was left entirely undeveloped.[5] Stubbs could then employ such a study against grounds of his patrons’ choosing, as in his repetition of his finished study Eclipse for Eclipse with William Wildman and his sons, John and James (c.1769; The Baltimore Museum of Art).[6] The degree to which constituent parts remained separable, however, is indicated by Benjamin Green’s print of this painting that included only Eclipse and John Wildman against a different landscape that was issued independently in 1772, then as part of a drawing book around 1777.[7] Perhaps it was at this stage, when the central subject was finished, that a dialogue with Stubbs’s patrons finalized the choice of surrounding ground.

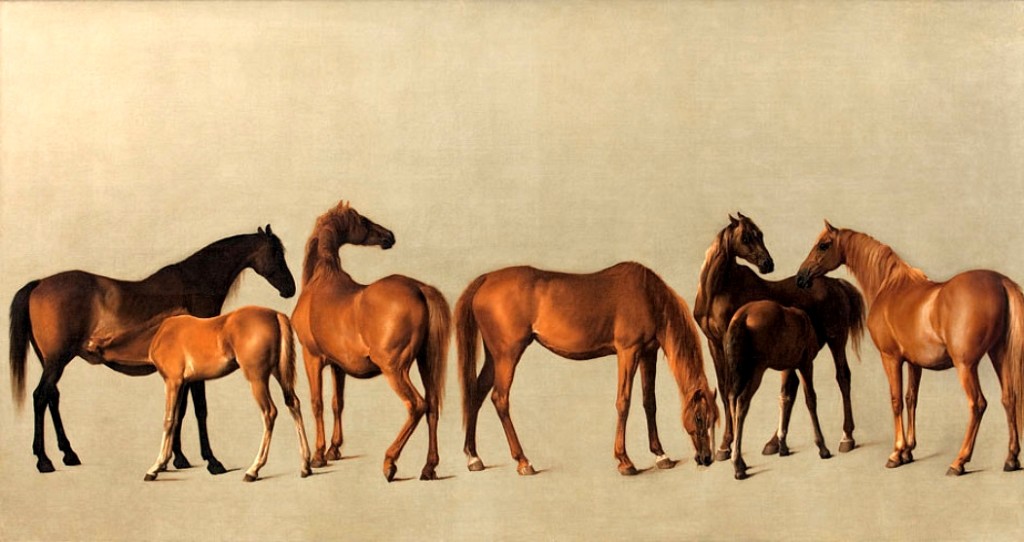

Fig. 2. George Stubbs, Mares and Foals, oil on canvas, 1762. Private collection. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 3. George Stubbs, Whistlejacket, oil on canvas, 1762. National Gallery, London. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Two of Stubbs’s most celebrated canvases, Mares and Foals (1762) (Fig. 2) and Whistlejacket (1762) (Fig. 3), both painted for Charles Watson-Wentworth, 1st marquess of Rockingham, provide further evidence of this stage arrested, in these cases, quite remarkably by their patron mid-process. In Ozias Humphrey’s manuscript biography of Stubbs based on conversations with the artist he relays that Rockingham wished Whistlejacket to be “represented by the best portrait painter, and the Landscape back ground by the best artist in that branch of painting; hoping by an union of talents to possess a picture of the highest excellence.”[8] Egerton notes that Stubbs’s contemporaries were particularly harsh on his landscapes. In 1775 a critic wrote that Stubbs should either improve his skill in landscape or “get somebody else to do them for him;” in her manuscript catalogue of paintings at Castle Howard in 1837, Georgiana Dorothy, countess of Carlisle, described a painting that her husband had commissioned in 1773 and observed that Stubbs’s “inability to paint landscape or suffer any other artist to supply his defect (which was requested) renders this piece less valuable.”[9] As Stubbs reached the final stages of Whistlejacket, at the “last sitting, or rather standing” according to Humphrey, the horse responded so violently to the verisimilitude of his own likeness that he approached to attack and was calmed only by the stable-boy’s switch and Stubbs’s maulstick. “The Marquis came shortly after to see what progress had been made, & learning the circumstances, was so pleased with such proof of excellence of the picture that he determined nothing more should be done to it, tho’ it was on the bare canvas without a background.”[10]

Art historians have been eager to read Rockingham’s interest in classical sculpture as the motivating force behind the remarkable, five monochrome-ground horse portraits that he commissioned from Stubbs. Surely this was not their ultimate point of origin, however, but a condition that encouraged Rockingham to appreciate a step in Stubbs’s already operative, even standard, working process. This order is suggested by Humphrey’s narrative (unpublished in full until 2000 and oddly absent from most accounts of the Rockingham group)[11] and comparison with other works in Stubbs’s œuvre. The role of the Rockingham paintings as, in part, working objects is emphasized by Stubbs’s repetition of the animal groups at far left and far right in the frieze-like composition of Rockingham’s Mares and Foals for a similar subject with landscape ground probably painted for George Brodrick, 3rd viscount Midleton (c.1763–65) (Fig. 4) and further repetition of the group at right in another Mares and Foals against an alternate landscape for Robert, 2nd earl Grosvenor (1764; private collection).[12] Appreciation of the Rockingham group has been misinformed by the diverted, beautiful studio object.

Fig. 4. George Stubbs, Mares and Foals, oil on canvas, c.1763–65. Tate Britain, London. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 5. George Stubbs, Newmarket Heath, with the 4-Miles Stables Rubbing House at the Start of the Beacon Course, oil on canvas, c.1765. Tate Britain, London. Image: © Tate, London 2016.

Despite art historians’ desire to read them with a post-Romanticist sensibility, Stubbs’s eerily empty landscape paintings are probably best understood as the direct compliment to these highly finished animal studies. Two views of Newmarket Heath (c.1765) (Fig. 5) and (c.1765; Yale Center for British Art) remained in Stubbs’s studio until his posthumous sale and serve as the alternate backgrounds, exchangeable as scrims, behind which his animal actors might play. They are repeated in Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath (c.1765; Private Collection), Gimcrack with John Pratt up at Newmarket (c.1765; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge), Turf, with Jockey up, at Newmarket (c.1766; Yale Center for British Art) – and, nearly forty years later, in Stubbs’s mannerist masterwork, Hambletonian, Rubbing Down (1800) (Fig. 6).[13] With the discrete poles of horses on monochrome grounds on one end and unpopulated landscape grounds on the other, the vast majority of Stubbs’s finished work appears as a third term or composite product and the artist’s working methods reveal themselves with remarkable clarity. That most patrons saw this initial stage of isolated motifs by genre as unresolved is clear from the later history of one painting from the Rockingham group, The Black Stallion Sampson, Portrayed from Three Angles (c.1764) (Fig. 7).[14] Recorded by Humphrey as “without background,” it acquired a dramatic, autumnal Lorrainian horizon and foliage sometime after Rockingham’s death in 1782.[15] Egerton notes other canvases that attained landscapes in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries (variations in condition and limited access for many works in private collections could well reveal more).[16]

Fig. 6. George Stubbs, Hambletonian, Rubbing Down, oil on canvas, 1800. Mount Stewart, The National Trust. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 7. George Stubbs with additions by another landscapist, The Black Stallion Sampson, Portrayed from Three Angles, oil on canvas, c.1764. Private collection. Image: © Courtesy of C. Simon Dickinson Limited, London.

Bolingbroke’s horse would not race until 1769, when it was given the name Hollyhock. Because portraits of unbroken yearlings that had not yet debuted at the racetrack were considered bad luck it seems likely that Stubbs’s finished study held an awkward status upon completion: valued for its author, it was handicapped by its subject and incomplete state. Having already painted four large-scale commissions for Bolingbroke between 1761 and 1764, Stubbs may have offered his patron the sketch as a gift or bid for additional, future work.[17] Its instability presumably encouraged its reformulation, almost immediately, as a gift in turn. Its eighteenth-century label notes, “This painting was given to Monet on his last trip to England in 1766 by Lord Boolenbrock [sic].”[18] “Monet” has been convincingly identified as Jean Monnet, the theater impresario and entrepreneur who purchased the privilège for Paris’s Opéra comique in 1743, overhauling it with the aide of Charles-Simon Favart, Jean-Georges Noverre and Boucher to such success that it was later shut down by the royal authorities.[19] An intimate of David Garrick, Monnet held deep connections to England, where he had tried unsuccessfully to import French theater. In a thank-you letter to Garrick, who had lent him use of his home in Southampton Street for his visit in 1766, Monnet playfully commented on the English luminaries with whom he had made contact that season: “You see, my friend, that I do not mix with the scum of the land.”[20] Despite Bolingbroke’s arguable status in these years as “scum,” he may well have been amongst those Monnet encountered. Whether the painting was given to or purchased by Monnet or – perhaps more likely – Monnet acted only as an agent remains unclear, however. The latter possibility is encouraged by its subsequent provenance by 1774 with another sometime Anglophile and rake, Jean, comte du Barry, the man responsible for brokering the legalities of his sister-in-law’s elevation to maîtresse-en-titre to Louis XV.[21]

Boucher’s death on May 30, 1770 provides a terminus ad quem for the additions to Stubbs’s canvas because his figures are painted over the landscape ground (which shows through the girl’s basket and the boy’s head). Monnet’s patronage of Boucher is well-documented beginning with set designs and costumes for Favart’s Le Coq du village (1743) and the complete interior decoration of Monnet’s theater built at the Foire Saint-Laurent in 1753.[22] Boucher also appears in Monnet’s correspondence with Garrick. In August 1765 Monnet reported the news, “My friend Boucher is made first painter to the King, with a pension of 6000 livres.”[23] On March 16, 1769, he writes, “I still have a painting, of which I would like to rid myself, painted by Boucher twenty years ago; this painting is voluptuous, and all the same too nude for a man my age; it is a crouching woman exiting her bath; it is colorful; I will show it to M. Lascelles [presumably, Edwin Lascelles, 1st Earl Harewood] at the end of the month; I hope you will help in selling it to him; I hope to sell it for thirty pounds.”[24] Monnet’s relationship with Boucher lasted until his death. Georges Wille’s diary records a dinner on February 13, 1770 given by fellow engraver Pierre-François Basan at which Boucher and Monnet were both in attendance.[25]

Monnet did not directly patronize Vernet but acted as his agent for the Englishman Sir John Thornhill exactly during the relevant period, for pendant seascapes in May 1764 at 1,500 livres, then for another pair representing calm and stormy seas in January 1766, for which Thornhill paid, via Monnet, 2,400 livres in 1770.[26] In his livre de raison, Vernet in fact refers to Thornhill as “Anglois et de la connoissance de M. Monnet.”[27] Midway through this affair, on May 20, 1765, Monnet wrote to Garrick, “Do not forget, my friend, to go with Mrs. Garrick to see the four paintings by Boucher and Vernet, at Mrs. Thornhill’s residence, Berkeley Square.”[28] It seems that he also introduced Garrick to Vernet on the Englishman’s brief visit to Paris. In his daybook for March 1765 Vernet recorded Garrick’s commission of a small painting “of my fantasy […] promised as soon as I am able.”[29] Monnet was clearly actively involved in developing a market for contemporary French painting in England prior to his better-known letters of introduction in 1771 for Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg that resulted in this artist’s extensive work for Garrick’s Drury Lane Theater.[30]

Monnet was well positioned, therefore, to act as coordinator of works between three of Europe’s leading painters in the period 1766 to 1770. How Hollyhock moved from Monnet to du Barry is not known, though Monnet’s role as art agent – perhaps one attempting to curry favor with du Barry – provides a likely possibility. When du Barry’s collection was sold in 1774, Hollyhock appeared under “Tableaux de différentes Ecoles.” Omitting Stubbs’s name altogether, the text describes, “An English horse; M. Vernet made the landscape that serves as a ground, M. Boucher enriched it with two figures & several animals. This painting on canvas is all the more considerable in that three able artists have exercised their talents here, each according to his genre.”[31] The work sold to Monnet for a notably low 175 livres. A larger pastoral by Boucher made 600 livres and a Vernet seascape 2,350 livres.[32] Beyond the question of the technical complexity of such a composite work, its awkward historiographic position in terms of authorship is suggested by the catalogue’s text. In a French context, where Stubbs was little known and the concept of an English school only beginning to take shape, French academicians were emphasized.[33] Hollyhock’s history after Monnet’s death in 1785 is unknown, but it next reappeared in England, where its subject and first author returned to the fore. The Sporting Magazine of January 1803 included John Scott’s engraving of Hollyhock described as “one of the most beautiful [paintings] ever seen” – and, by way of explaining its triple authorship (all three of whom were correctly identified in an exact translation of the label on its stretcher), “At present, we have it only in our power to state that the original picture was given to Mr. Monnet, when he was last in England, in 1766, by Lord Bolingbroke.”[34] Auctioned again in 1810, it sold via the art dealers Colnaghi to perhaps its ideal collector, the Francophile prince regent and future George IV, in whose manuscript collection catalogues all three painters are listed alongside the note “A very curious and singular picture.”[35]

Workshop Practice and the Status of Painting in Eighteenth-Century Europe

It would be a mistake to normalize Stubbs, Vernet and Boucher’s creation. But it might still be asked what, upon arrival in France, allowed for Stubbs’s oil sketch to be received and then transformed through a process that seems so extraordinary today? By way of an answer that is intended to gesture to much broader questions about artistic production in early modern Europe, I would like to outline three understudied categories of objects linked by similar technical procedures and ways of artisanal thinking: old master canvases to which collectors or dealers requested that artists make changes; canvases that were collaborative from the outset; and the arabesque. This last mode of decorative painting with a structured division of the surface by painters according to specialty alerts us to the proximity of multiple hands to the practice of decoration and, eventually, the proximity of painting in this moment to the decorative arts. What links each of these groups and, ultimately, England and France, is a basic means of manipulating images in early modern Europe that was undergoing reframing along ideological lines, as realities of production were given new meaning between private schools, like Saint Martin’s Lane, and the Royal Academy in London, or the Académie de Saint-Luc and Académie royale in Paris.[36]

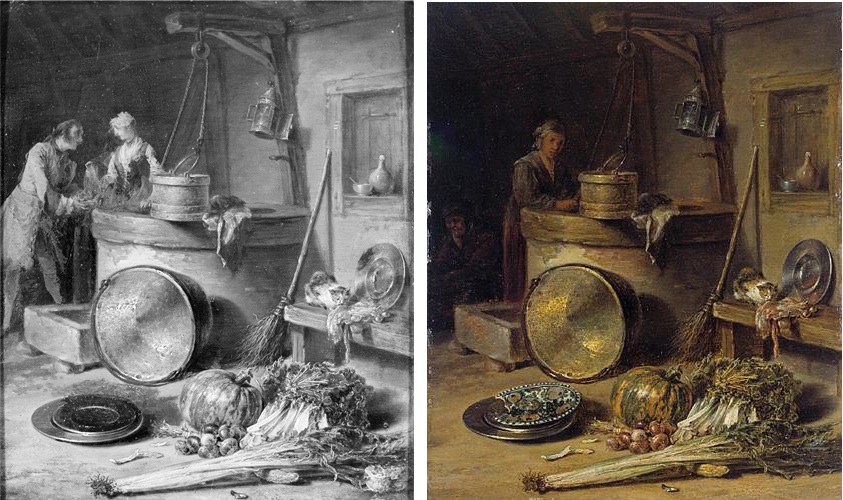

LEFT: Fig. 8. Willem Kalf with additions by Nicolas Lancret, Kitchen Interior, oil on panel, c. 1645 / c.1735. Photograph before conservation. The Saint Louis Museum of Art. Image courtesy of The Frick Art Reference Library.

RIGHT: Fig. 9. Willem Kalf, Kitchen Interior, oil on panel, c. 1645. Photograph after conservation. The Saint Louis Museum of Art. Image: Wikiart.

Just how malleable paintings were to eighteenth-century collectors, dealers and artists is driven home by the extensive practice of altering canvases by well-respected masters to suit decorative constraints, add visual interest or spark witty juxtapositions of old and new.[37] Symmetry was an abiding principle of most eighteenth-century hangs and this alone seems to have determined many structural alterations.[38] In 1807 a sales catalogue listed a fête galante by Watteau that “was enlarged all around, in order to serve as a pendant to another subject.”[39] Modifications could also take place on a more limited, reversible scale, however. Watteau’s follower, Nicolas Lancret, made a business of adding fashionably dressed eighteenth-century figures to seventeenth-century Dutch interiors. At least six are recorded atop panels by or once attributed to David Teniers or Willem Kalf.[40] The ground of one example, Picking Fleas (Kitchen Interior) (c.1643/c.1735; The Wallace Collection, London), is typical of Kalf’s interiors from the 1640s that were prized on the eighteenth-century Parisian art market.[41] Probably around 1730 Lancret added a servant girl provocatively searching for fleas, a subject that enjoyed popularity as a sexually alluring literary topos and that x-rays reveal covers Kalf’s less titillating, old servant woman.[42] Removal of Lancret’s additions to a Kalf in the Saint Louis Museum of Art during the 1960s suggests why few examples survive (Figs. 8 & 9). Textual records studied extensively by Martin Eidelberg underscore the sizable place such paintings once held in the art market, however.[43] To cite but two, “A beautiful landscape [by Jan Breughel] in which Jean-Baptiste Oudry painted, in his spare time, several dogs chasing a stage” appeared in Joseph Aved’s 1766 sale, while a “Rest of Diana [by Boucher] enriched with game animals and dogs by Oudry” was part of an anonymous sale in London in 1810.[44] Such works bleed into an obvious corollary in which distinct sections of the same canvas were executed by contemporaries. As a studio practice this is well known and studied for earlier, northern European painters – especially for Rubens who regularly collaborated “horizontally” (in Hans Vlieghe’s felicitous term) with Breughel and Frans Snyders.[45] In the eighteenth century this kind of production, while descended from collaborations structured by Charles Le Brun and the Batîments du Roi, was increasingly associated with the mercantile context of the Pont Notre-Dame rather than with academicians showing at the Salon or submitting works for professional advancement, the various concours or the prix de Rome, in which the consolidation of the author in direct relationship to the work was essential.[46]

Fig. 10. Jean Millet II with additions by Antoine Watteau, The Flutist, oil on panel, c. 1716. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Grenoble. Image: © Musée de Grenoble.

One of the most famous anecdotes of eighteenth-century French painting is that of Watteau’s early period in the Pont Notre-Dame, where cheap, servile copies were allegedly produced “by the dozen.”[47] Edme Gersaint, himself a dealer on this bridge, disapprovingly described Watteau in an assembly-line: one journeyman “created the skies, another the heads; these here the draperies; those there the highlights; until at last the painting was finished and left the hands of the last of them.”[48] This was an additive, collaborative situation; highly practical, it resulted in proto-mechanized production. When, in 1748, the comte de Caylus read his biography of Watteau to the Académie royale he judgmentally drew on similar threads about Watteau’s time in the Pont Notre-Dame.[49] For Caylus this was what Watteau the artist had to overcome. Of course, as Caylus reports and Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat’s catalogue raisonné of his drawings makes mind-bogglingly clear, Watteau did repeat given figures in his paintings (established first in drawings) and did so in a pattern-book like manner. But there is also substantial evidence of Watteau providing staffage for Antoine Dieu, Jean-François (Francisque) Millet, Michel Boyer, Philippe Meusnier and Jean-Baptiste Foret. The Flutist (Fig. 10) is one of the few preserved examples: on a ground attributed to Millet, Watteau added his signature figures.[50] In 1752 Dezallier d’Argenville described a painting at Versailles of a church interior by Meusnier for which Watteau was commissioned to paint “pretty figures” (if accurate, this would be by far Watteau’s highest level commission);[51] after visiting the studios of Meusnier and Watteau in 1715 the Swedish diplomat Carl Gustaf Tessin reported that their regular collaboration was well known.[52] And, as Christian Michel has emphasized, these collaborative practices long outlasted Watteau’s early, Pont Notre-Dame period.[53]

LEFT: Fig. 11. Nicolas de Largillière and Jean-Baptiste Belin, Hélène Lambert de Thorigny, oil on canvas, c. 1696–1700. The Honolulu Museum of Art. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

RIGHT: Fig. 12. Nicolas de Largillière, Study of Hands, oil on canvas, c.1713–1714. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

While Watteau is typically portrayed as an idiosyncratic outsider to academic practice, the concept of multiple hands in the Pont Notre-Dame finds an elevated counterpart in Oudry. His father, a member of the guild, was in fact a dealer in the Pont Notre-Dame and Oudry trained in the studio of Nicolas de Largillière, an academic portraitist with an immense production facilitated by a large team of assistants.[54] These assistants worked according to specialty by genre – in some cases collaborating “horizontally” with outside contractors, as documented in works like Largillière’s Hélène Lambert de Thorigny for which the flower-painter Jean-Baptiste Belin supplied an encircling garland (c. 1696–1700) (Fig. 11).[55] An anecdote relays that Oudry discovered his talents as an animalier that would ultimately secure his fame while completing a dog for a portrait in his master’s studio.[56] Portraitists like Largillière frequently executed works according to a set group of studio models recorded in oil sketches of hands, lace and other still-life elements (Fig. 12).[57] Like Stubbs’s studies these magnificent workshop tools have been too regularly transformed by post-Romanticist notions of the fragment into poetic still lives, but given their clear role in the studio they might be understood more productively and specific to their historical moment as luxurious model books.[58] The ledgers of Largillière’s contemporary Hyacinthe Rigaud attest to the way in which the assignment of individual portions of the canvas were consistently given to specialist painters working from such models – either newly developed for the patron or recycled.[59] The same hand, arm, furnishing or flowers can be tracked across portraits of multiple sitters.[60] Rigaud’s ledgers demonstrate economic motivations for this practice: the more recycling of already established motifs and the greater the number of assistants engaged, the cheaper the portrait. Like ormolu or porcelain molds for artisans in other trades, once established for a prestigious client certain replicable components might serve the studio for years.

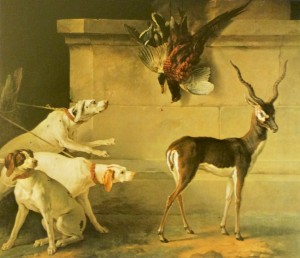

Fig. 13. Jean-Baptiste Oudry (and studio?), Indian Blackbuck, oil on canvas, 1739. Staatliches Museum, Schwerin. Image: © Staatliches Museum Schwerin.

Fig. 14. Jean-Baptiste Oudry (and studio?), Indian Blackbuck, Three Dogs and Pheasants, oil on canvas, 1745. Blessington Collection, Russborough House, Ireland. Image used with permission of Russborough House.

There are many reasons to believe that once Oudry transitioned from assistant to master he operated according to such working principles. This was ingrained from his training but, like Watteau, he too retained a collection of drawn motifs with particular assiduity. The abbé Gougenot stated that Oudry was more attached to his drawings than to his paintings and he considered them a resource to be left to his family.[61] Unsurprisingly, perhaps, like Watteau, Oudry regularly repeated a given unit of visual information once established: a means of working that was well suited to distributing labor between assistants in his large studio (Figs. 13 & 14). But by the time Oudry was practicing as a mature master in the 1740s he actively denied this reality of his practice – even if his slightly older competitor, Alexandre Desportes, allegedly said that he “liked works by Oudry well enough when they were entirely by his hand.”[62] In Oudry’s conférence to the Académie royale in 1749 he spoke out against workshop collaboration. At least for the audience of the Académie, Oudry characterized studio assistance as “infinitely dangerous”: “[R]egardless of whether the person chosen to do the filling-in is competent or not,” it “introduces a false element into your work that will not fail to strike the viewer” – and result in a lack of overall unity.[63] However, Oudry’s repetition of a figure once established suggests otherwise and, in many instances, discrepancies of the divided canvas are, in fact, felt exactly as his conférences described. For Oudry’s reiterations of an Indian Blackbuck this is true simply at the level of composition with the bizarre relationship (or lack of relationship of the sort usually associated with Watteau) between the placid buck and eager dogs. In order to emphasize this point it is useful to look at a detail of the legs in the monumental version from 1739 with its peculiar disconnection between figure and ground (Fig. 15). In short, a painting made in this way risks becoming a composite of so many discrete objects – the awkward epitome of which is something like Stubbs, Vernet and Boucher’s Hollyhock.

If we return to the genre of portraiture the kinds of literal breaks that this suggests are not so foreign, even at the most literal level. Portraitists frequently completed three-quarters or full-length portraits by executing the head of the sitter on a small piece of canvas or paper and later attaching this to the larger work. Comparable with Largillière’s collaborations with Belin, Boucher’s pastel Madame de Pompadour with Attributes of the Arts (1754; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne) (Fig. 16) is a prime example of a single sheet with multiple authors (most likely Boucher for the head, assistants for the surround), though the same method for attaching literally separate supports for portrait heads in the imago clipeata tradition was used in some of Pompadour’s most celebrated likenesses, including Maurice-Quentin de La Tour’s pastel (1749–1755; musée du Louvre), François-Hubert Drouais’s Madame de Pompadour at her Tambour Frame (1763–1764; National Gallery, London), Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour at her Toilette (1750/c.1760; Harvard Art Museums) and Marquise de Pompadour (1756; Alte Pinakothek, Munich), for which Alexandre Roslin was said to have executed the sumptuous lace.[64] Moreover, the heads of royal sitters in particular were frequently the subject of repetition between settings or even bodies across prints and paintings in a longstanding and efficient means of propagating images of the king and his court.[65]

Fig. 16. François Boucher and studio, Madame de Pompadour with Attributes of the Arts, pastel on blue paper, 1754. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

It is from this context of multiple hands operating in a workshop context and the canvas as a potentially fractured surface that I would like finally to step into the realm of decoration, specifically the arabesque. Without the structuring of a perspectival, typically rectilinear window that lends a unity – however tenuous – to the works discussed thus far, the arabesque’s system of discrete parts lays bare a collaborative, combinatory modality with greater clarity, albeit in a decorative context that has largely normalized the resultant flat, pattern-like effect as discrete pieces build out to cover a given surface.

Fig. 17. Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Arabesque (La Chasse from the château de Voré), oil on canvas, c. 1720 – 1723. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

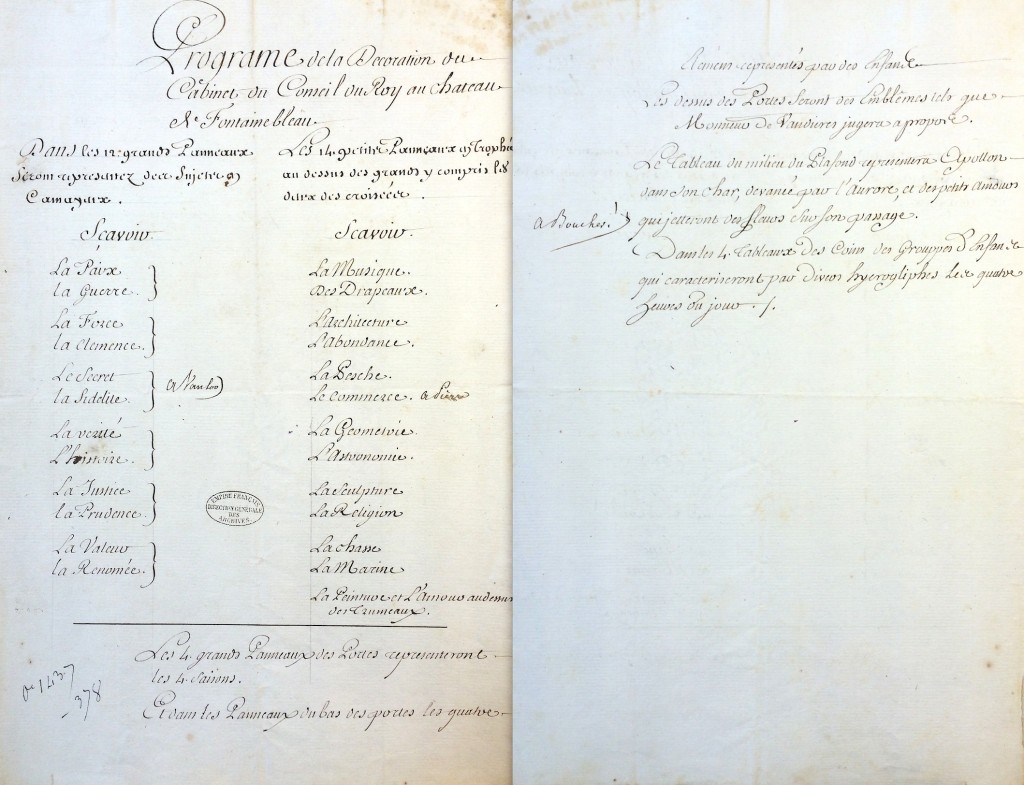

As developed by the Audran family, the arabesque dominated decorative painting in France from the end of the seventeenth century well into the 1720s.[66] With few surviving finished works, it is difficult to recapture the tremendous impact of their workshop and its place as a training ground for the many artists in their employ, including Watteau, Desportes, and Oudry (i.e. Fig. 17).[67] Division of arabesque work by specialists according to genre is most relevant here. The role of someone like Claude III Audran was to approve an overall design to which flower, figure, animal and ornament painters made unique contributions (such as this arabesque design from the Audran workshop). As Daniel Crönstrom discovered to his frustration when attempting to recruit a decorative painter for the Swedish court these artists operated less as individual masters than as large teams.[68] The arabesque’s structure was, of course, entirely sympathetic to this kind of collaboration under one coordinator of work. Within an exacting symmetry, reserves were left throughout awaiting the insertion of an endless variety of discrete animal, vegetal or figural units. According to Caylus in his biography of Watteau, Audran “would reserve places in these sorts of compositions for different subjects to be determined by the wishes of the individuals decorating their ceilings and paneling in this genre.”[69] We might think here of collectors’ understanding of the malleability of old master paintings. A material manifestation of this approach to the individuated unit in surviving drawings is the regular appearance of layered options tipped in on a given design that provided Audran or his client with a series of alternate motifs (Fig. 18). The phenomenon of specialists coordinated by someone like Audran – or, in the painter’s studio, by Largillière or Oudry – was of course entirely commonplace in many realms of object making. Not least of these was tapestry production under the name of Le Brun, France’s ultimate coordinator of works, whose title is often used as shorthand for many individual contributing designers. Account books typically list payment to five or six artists specialized by genre. The surface’s divisibility was underscored, moreover, by the usefulness of compositions that could be broken apart to fill out different quantities of wall surface: individual commissions having to take into account already present configurations of doors, chimneypieces and windows. This division of labor and finances is also found in decorative projects produced by artists at the peaks of their careers, as in the salle du Conseil at Fontainebleau in which a roughly arabesque structure organizes paintings by Boucher, Carle Van Loo and Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre framed by Alexis Peyrotte’s floral decoration (c.1753) (Fig. 19).[70] The break-down by genre and artist in this space is echoed in the archival records for the project, in which the marquis de Marigny, in his capacity as directeur des Batîments du Roi, annotated the architect Ange-Jacques Gabriel’s program with the names of the artists he thought suitable for discrete portions, including “À Boucher!” for the ceiling cloisons (Fig. 20).

LEFT: Fig. 18. Audran workshop, Arabesque design with tipped-in elements, c. 1710. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Image used with permission of Nationalmuseum Stockholm.

RIGHT: Fig. 19. Salle du Conseil, château de Fontainebleau, c.1753. Overall design by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, carving by Jacques Verberckt, and paintings by François Boucher, Carle Vanloo, Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre and Alexis Peyrotte. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 20. Abel François Poisson de Vandières, marquis de Marigny et de Ménars annotations to Jacques-Ange Gabriel, “Programme de la decoration du cabinet du conseil du Roy au château de Fontainebleau”, undated (c. 1752). Archives nationales, O1 1437-378 recto/verso. Image used with permission of Archives nationales de France.

Fig. 21. Martin Carlin and Charles-Nicolas Dodin, Guéridon, Sèvres hard-paste porcelain, mahogany and gilt-metal, 1774. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: © RMN-Louvre, Paris.

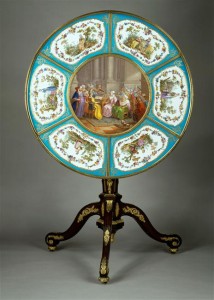

Having moved to the arabesque, I would like to conclude resoundingly, if rapidly, on the decorative arts through one, final object. In 1774, the marchand-mercier Simon-Philippe Poirier delivered a tripod table known as a guéridon to Madame du Barry at her recently completed château de Louveciennes (Fig. 21). Its mahogany body was carved by Martin Carlin and its tilt-top was composed from seven Sèvres plaques enameled by Charles-Nicolas Dodin based on prints that reproduced figural vignettes by Watteau and, at the center, The Grand Turk giving a Concert to his Mistress (1737; The Wallace Collection) by Van Loo.[71] It makes a revealing comparison with the Stubbs-Vernet-Boucher with which this article opened. Simple categorization of these two objects by medium (oil on canvas versus mahogany, porcelain and ormolu) – or even, as a direct corollary, the professionals that brought them into being (Stubbs, Vernet and Boucher versus Poirer, Carlin and Dodin) – seems neatly to distinguish them between fine and decorative arts. However, the defining feature of both of these objects is surely not medium or maker but the peculiar way in which they were produced as assemblages of discrete parts, the contributions of multiple hands. Or, if this seems an epilogic bridge too far, perhaps a better comparison is made with Fontainebleau’s salle du Conseil in which the brushes of Boucher, Van Loo, Pierre and Peyrotte – their actual hands applying paint to canvas and panel – were at work knitting together a single décor. Looking at objects like Hollyhock that are difficult to categorize, we are, perhaps, more easily aware of the constraints in which we study – and, at times, simplify so as to make sense of – the complexity of history told through objects and our burden of continuing to work with terms that shy away from the language of craft and commerce, themselves largely inherited from eighteenth-century institutions and writers on the arts.

David Pullins is completing his doctoral dissertation, Cut & Paste: the Mobile Image from Watteau to Pillement, at Harvard University

Acknowledgements: Many thanks are due to the editors of Journal18 for the invitation to contribute to this inaugural issue, to the anonymous reviewers, and especially to Alastair Laing, Mark Ledbury and Nicola Christie for discussing Hollyhock with me.

[1] “Ce Tableau a été donné à Monet dans un dernier voyage en Angleterre dans l’année 1766 par Lord Boolenbrock [sic]. Le cheval a été peint par Stubbs actuellement à Londres, le fond du tableau par Vernet, célèbre peintre de Marine, et les deux figures, le chien et les moutons par Boucher, premier peintre du Roi de France.”

[2] Judy Egerton, George Stubbs, Painter. Catalogue Raisonné (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), no. 155. Florence Ingersolle-Smouse, Joseph Vernet. Peintre de Marine, 2 vols. (Paris: Étienne Bignou, 1926), II, no. 1388; Alexandre Ananoff and Daniel Wildenstein, François Boucher, 2 vols. (Lausanne and Paris: La Bibliothèque des arts, 1976), II, 328.

[3] With art collecting as a strain within natural history collecting, as in Krzysztof Pomian, Collectionneurs, amateurs et curieux: Paris, Venise, XVIe–XVIIe siècle (Paris: Gallimard, 1987), 163–88.

[4] Bolingbroke purchased Hollyhock in 1765. Egerton, George Stubbs, 149.

[5] Egerton, George Stubbs, nos. 27, 74.

[6] Egerton, George Stubbs, no. 76.

[7] Christopher Lennox-Boyd, Rob Dixon and Tim Clayton, George Stubbs. The Complete Engraved Works (New York: 1989), no. 32.

[8] Ozias Humphrey, “Memoir” (Joseph Mayer Papers, Liverpool City Libraries, dated c.1794–1797) in Fearful Symmetry. George Stubbs, Painter of the English Enlightenment, ed. Nicolas Hall (New York: Hall and Knight, 2000), 200–201.

[9] London Evening Post, May 6–9, 1775. Egerton, George Stubbs, 81 and no. 155.

[10] Humphrey repeated such Zeuxian formulas four times in his “Memoir.” Fearful Symmetry, 205, 208–209.

[11] On the text see Brian Allen in George Stubs, 1724–1805. Science into Art, ed. Herbert W. Rott (Munich: Prestel, 2012), 90.

[12] Egerton, George Stubbs, nos. 62, 63.

[13] Egerton, George Stubbs, nos. 68–72, 336.

[14] Egerton, George Stubbs, no. 54.

[15] H. Frank Constantine, “Lord Rockingham and Stubbs, Some New Evidence”, The Burlington Magazine, 95, no. 604 (July 1953): 237.

[16] Egerton, George Stubbs, p. 81, nos. 54, 103.

[17] Egerton, George Stubbs, nos. 17, 19, 23, 26.

[18] “Ce Tableau a été donné à Monet [sic] dans un dernier voyage en Angleterre dans l’année 1766 par Lord Boolenbrock [sic].”

[19] Jean Monnet, Supplément au Roman comique; ou, Mémoires pour servir à la vie de Jean Monnet, 2 vols. (London [i.e., Paris]: 1772); “Jean Louis Monnet” in Philip Highfill, Jr., Kalman Burnim and Edward Langhans, A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800, 16 vols. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1974–), X (1984): 279–83; Mark Ledbury, “Boucher and Theater” in Rethinking Boucher, ed. Melissa Hyde and Mark Ledbury (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2006), 133–60; Mark Ledbury, Sedaine, Greuze and the Boundaries of Genre (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2000), 62–67.

[20] Frank Arthur Hedgcock, A Cosmopolitan Actor. David Garrick and his French friends (New York: B. Blom, 1969), 395.

[21] On the collection see Émile Dacier, Catalogues de ventes et livrets de Salons illustrés par Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, 6 vols. (Paris: Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1909–1921), III, 11–18.

[22] Monnet, Supplement au Roman Comique, I, 60.

[23] “Mon ami Boucher est premier peintre du Roi, avec 6000 l. de pension.” The Private Correspondence of David Garrick, ed. James Boaden, 2 vols. (London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1831-1832), II, 452.

[24] “J’ai encore un tableau dont je veux me défaire, peint par Boucher il y a vingt ans; ce tableau est volupteueux, et même trop nud pour un homme de mon âge; c’est une femme couchée qui sort du bain; il a de la couleur; je l’enverrai sur la fin de ce mois à Mr. Lascelles; je compte que vous voudrez bien concourir avec lui pour le faire vendre; je veux le vendre trente Louis.” Boaden, ed., The Private Correspondence of David Garrick, II, 556. No evidence exists to suggest the sale, however. My thanks to Alistair Laing and the curators at Harewood House, Leeds, for their consultation on this.

[25] Mémoires et journal de J.G. Wille, graveur du roi, ed. George Duplessis, 2 vols. (Paris: Renouard, 1857), I, 424.

[26] Vernet’s “livre de verité” (Médiathèque Ceccano, Avignon) transcribed in Léon Lagrange, Joseph Vernet et la peinture au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Didier, 1864), 343, 346, 366.

[27] Lagrange, Joseph Vernet, 434. My thanks to Alistair Laing for helping build out this picture of the Thornhill-Vernet-Monnet relationship.

[28] “N’oubliez pas, mon ami, d’aller avec Madame Garrick voir les quatre tableaux des Messrs. Boucher et Vernet, chez Mrs. Thornhill, Berkeley Square.” Boaden, ed., The Private Correspondence of David Garrick, II, 438.

[29] “à ma fantasie […] promis pour le plustot que je le pourray.” Vernet’s “livre de verité” in Lagrange, Joseph Vernet, 344.

[30] Ellis K. Waterhouse, “English Painting and France in the Eighteenth Century,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 15 (1952): 133–34; Ingersolle-Smouse, Joseph Vernet, no. 820; Olivier Lefeuvre, Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg, 1740–1812 (Paris: Arthena, 2012), 32–33, 329, 367–68.

[31] “Un cheval anglois; M. Vernet a fait le paysage qui sert de fond, M. Boucher l’a enrichi de deux figures & de plusieurs animaux. Ce tableau peint sur toile est d’autant plus à considerer, que trois Artistes habiles y ont exercé leurs talents chaucun dans leur genre.” Pierre Remy, Catalogue de tableaux […] le Cabinet de M.L. C. de D., 45. Gabriel de Saint-Aubin sketched all three interventions in his annotated copy (Musée du Petit Palais, LDUT 01155).

[32] My thanks to Mark Ledbury for drawing my attention to this.

[33] Olivier Meslay, “British Painting in France before 1802,” The British Art Journal, 4, no. 2 (Summer 2003): 14.

[34] The last sentence simply translates the French label listing the three artists. “Colt Bred by Lord Bolingbroke,” The Sporting Magazine, January 1803, 1.

[35] Christie’s, London, February 3, 1810, lot 71 (not in Egerton).

[36] The discomfort between theory and practice in the London context is embodied in Sir Joshua Reynolds’s paintings of John, 1st Earl Ligonier. Having painted his bust-length portrait in 1756-57 (National Army Museum, UK) Reynolds repeated the head and shoulders of the figure riding a horse in 1760 (Fort Ligonier, Ligonier, Pennsylvania; studio replica Tate, London). David Mannings, Sir Joshua Reynolds. A Complete Catalogue of His Paintings, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press 2000), I: 306-307 (nos. 1127, 1128). It has been speculated that the horse was designed by or possibly even painted by Stubbs. See Egerton, George Stubbs, 36.

[37] A process perhaps better studied for antique sculpture in early modern Europe. See, for example, the Melchior de Polignac collection with its restorations (often extensive re-imaginings) executing in contrasting stone. François de Poliganc, “Archéologie, prestige et savoire: visages et itinéraires de la collection du cardinal de Polignac” in L’Anticomanie. La collection d’antiquités aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, eds. Anne-France Laurens et Krzysztof Pomian (Paris: Ecole des hautes etudes en sciences sociales, 1992); Astrid Dosert, “Die Antikensammlung des Kardinals Melchior de Polignac” in Antikensammlungen des europäschen Adels im 18. Jahrhundert, eds. Dietrich Boschung and Henner von Hersberg (Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2000).

[38] For France, see Noémie Étienne, La Restauration des peintures à Paris (1750–1815). Pratiques et discours sur la matérialité des œuvres d’art (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2012); Colin B. Bailey, “Conventions of the Eighteenth-Century Cabinet de tableaux: Blondel d’Azincourt’s ‘La première idée de la curiosité,” The Art Bulletin, 69, no. 3 (September 1987): 431–47.

[39] “a été aggrandi tout autour, pour servir de Pendant à un autre Sujet.” Paris, May 25, 1807, lot 80.

[40] Georges Wildenstein, Lancret (Paris: G. Servant, 1924), 104–105; Georges de Batz, “French Cuisines,” Art Quarterly, 9 (1946): 307–11.

[41] A close comparative is A Kitchen Corner (c.1640; The Detroit Institute of Art). Lucius Grisebach, Willem Kalf (Berlin: Mann: 1974), 60.

[42] Stephen Duffy and Jo Hedley, The Wallace Collection’s Pictures: A Complete Catalogue (London: The Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 2004), 227; John Moffitt, “La Femme à la puce: The Textual Background of Seventeenth-Century Painted ‘Flea-Hunts’,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1987): 99–103.

[43] Martin Eidelberg, “The Case of the Vanishing Watteau,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 138 (July-August 2001): 15–40.

[44] “Un beau Paysage, dans lequel Jean baptiste [sic] Oudry a peint, dans son bon tems, plusieurs chiens qui courent au Cerf.” Paris, November 24, 1766, lot 15. “Repose de Diane, enrichi de gibiers et d’un chien peint par Oudri.” Paris, November 19–21, 1810, lot 14.

[45] Hans Vlieghe, “The Execution of Flemish Paintings between 1550 and 1700: A Survey of the Main Stages” in Concept, Design & Execution in Flemish Painting (1550–1700), eds. Hans Vlieghe, Arnout Balis and Carl Van de Velde (Turnhout: Brepols, 2000), 201. Anne T. Woollet and Ariane van Suchtelen, Rubens and Brueghel: A Working Friendship (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2006).

[46] On the Pont Notre-Dame’s rhetorical place see Mickaël Szanto, “The Pont Notre-Dame, Heart of the Picture Trade in France (Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries)” in Moving Pictures. Intra-European Trade in Images, 16th-18th Centuries, Studies in European History (1100–1800), eds. Neil De Marchi and Sophie Raux, vol. 34 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014), 76–91.

[47] A phrase found repeatedly in Vies anciennes de Watteau, ed. Pierre Rosenberg (Paris: Hermann, 1984), 12, 30, 44, 46.

[48] “faisaient les ciels, les autres faisaient les têtes; ceux-ci les draperies; ceux-la posaient les blancs: enfin le tableau se trouvait fini quand il pouvait parvenir entre les mains du dernier.” Gersaint in Vies anciennes, 31.

[49] Caylus in Vies anciennes, 57–58.

[50] For alternate attributions, Martin Eidelberg, “The Painters of the Grenoble ‘Flutist’ and Some Other Collaborations,” Art Quarterly, 32 (1969): 282–91.

[51] Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville, Abrégé de la vie des plus fameux peintres, 3 vols. (Paris: De Bove, 1752), p. 281. This painting was listed twice in the royal inventories but neither time with Watteau’s name, see Eidelberg, “The Painters of the Grenoble ‘Flutist’,” 291.

[52] Carl Nordenfolk, “L’An 1715” in Antoine Watteau (1684–1721). Le peintre, son temps et sa légende, eds. Margaret Morgan Grasselli and François Moreau (Paris: Champion-Slatkine, 1987), 31–33.

[53] Christian Michel, Le ‘célèbre Watteau’ (Geneva: Droz, 2008), 138–39.

[54] Hal Opperman in Largillière and the Eighteenth-Century Portrait, ed. Nan Rosenfeld (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1981), 310–39.

[55] Marianne Roland Michel, “Of Woman and Flowers,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 108 (July 1966): i-v. On this tradition, see Susan Merriam, Seventeenth-Century Flemish Garland Paintings. Still Life, Vision, and the Devotional Image (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012).

[56] “Mémoire pour Servir à l’Eloge de Mr. Oudry” in Hal Opperman, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, 2 vols. (New York: Garland, 1977), I, 169. Identification of the genre by which an artist’s fame would be secured in these critical terms of backhanded compliments is also found in Mariette’s remarks on Chardin.

[57] Rosenfeld, Largillière, 196–219; Emmanuel Coquery in Visages du Grand Siècle. Le portrait français sous le règne de Louis XIV (Paris: Somogy, 1997), 136–61.

[58] In this stance I differ from points recently made about the status of such works in Susanna Caviglia, “Life Drawing and the Crisis of Historia in French Eighteenth-Century Painting,” Art History, 39 (2016): 9–10.

[59] Le Livre de raison du peintre Hyacinthe Rigaud, ed. Joseph Roman (Paris: H. Laurens, 1919).

[60] Jean de Cayeux, “Rigaud et Largillierre, Peintres de mains,” Études d’art, VI (1951): 33–56.

[61] Louis Gougenot, “Vie de M. Oudry” (1761), in Mémoires inédits sur la vie et les ouvrages de Membres de l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Paris: J.-B. Dumoulin, 1854), 380.

[62] “Ce qui faisoit dire au célèbre Desportes, qu’il aimoit bien les Oudry quand itls étoient entièrement de sa main.” Gougenot, “Vie de M. Oudry,” 371.

[63] “un danger infini”; “il jette un faux dans votre ouvrage qui frappe également, soit que le maître que vous avez choisi pour faire vos remplissages se trouve habile ou qu’il ne le soit pas.” Oudry, “Réflexions sur la manière d’étudier la couleur en comparant les objets les uns avec les autres” (1749) in Le Cabinet de l’Amateur de l’Antiquaire, 3 (1844): 41.

[64] On technical aspects of these paintings – for this reality of their construction is rarely noted – see Alden Rand Gordon and Teri Hensick, “The Picture Within the Picture: Boucher’s 1750 ‘Portrait of Madame de Pompadour’ Identified,” Apollo (February 2002): 21–30. For entries, see Madame de Pompadour et les arts, ed. Xavier Salmon (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002), 148–50, 152–54, 160–64.

[65] For the phenomenon of official copies of royal portraits produced for the crown and the recycling of heads and bodies, see Claire Aubaret, “Les copistes du Cabinet des tableaux de la surintendance des Bâtiments du roi au XVIIIe siècle,” Bulletin du Centre de recherché du château de Versailles (2013).

[66] See especially Katie Scott, The Rococo Interior: Decoration and Social Spaces in Eighteenth-Century Paris (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996), 123–45, 154–161.

[67] Louis de Fourcaud, “Antoine Watteau, peintre d’arabesques,” Revue de l’art ancien et moderne, 24 (1908): 431–40 and 25 (1909): 49–59, 129–40; Martin Eidelberg, “Watteau and Audran at the Hôtel de Nointel,” Apollo, 115 (2002): 10–16; Opperman, Oudry, I, 70–72; Georges de Lastic and Pierre Jacky, Desportes (Saint-Rémy-en-l’Eau: Monelle Hayot, 2010), I, 30, 47–50, 99–115, 140.

[68] Daniel Crönstrom to Nicodemus Tessin, 2 July 1696 in Les Relations artistiques entre la France et la Suède, 1693–1718, eds. Roger-Armand Weigert and Karl Hernmarck (Stockholm: Egnellska Boktryck, 1964), 53.

[69] “les places qu’il y réservait, de recevoir différents sujets de figure et autres, à la volonté des particuliers qu’il avait su mettre dans le goût d’en faire décorer leurs plafonds et leurs lambris.” Caylus in Vies anciennes de Watteau, 60–61.

[70] Boris Lossky, “Le Plafond de François Boucher au Cabinet du Conseil du Château de Fontainbleau,” Revue du Louvre, 17 (1967): 257–64; Xavier Salmon, “Alexis Peyrotte (1699–1769) ou les graces du rocaille à Fontainebleau,” Les Dossiers de la Société des Amis et Mécènes du Château de Fontainebleau, 7 (2012): 1–32.

[71] Marie-Laure de Rocheburne, Le Guéridon de madame du Barry (Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2001).

Cite this article as: David Pullins, “Stubbs, Vernet & Boucher Share a Canvas: Workshops, Authorship & the Status of Painting”, Journal18, issue 1 (Spring 2016), https://www.journal18.org/334. DOI: 10.30610/1.2016.1

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.