Eguono Lucia Edafioka

Ukpon a tue re do omo.[1]

[It is the cloth one wears to which we will give the salute of chieftaincy.]

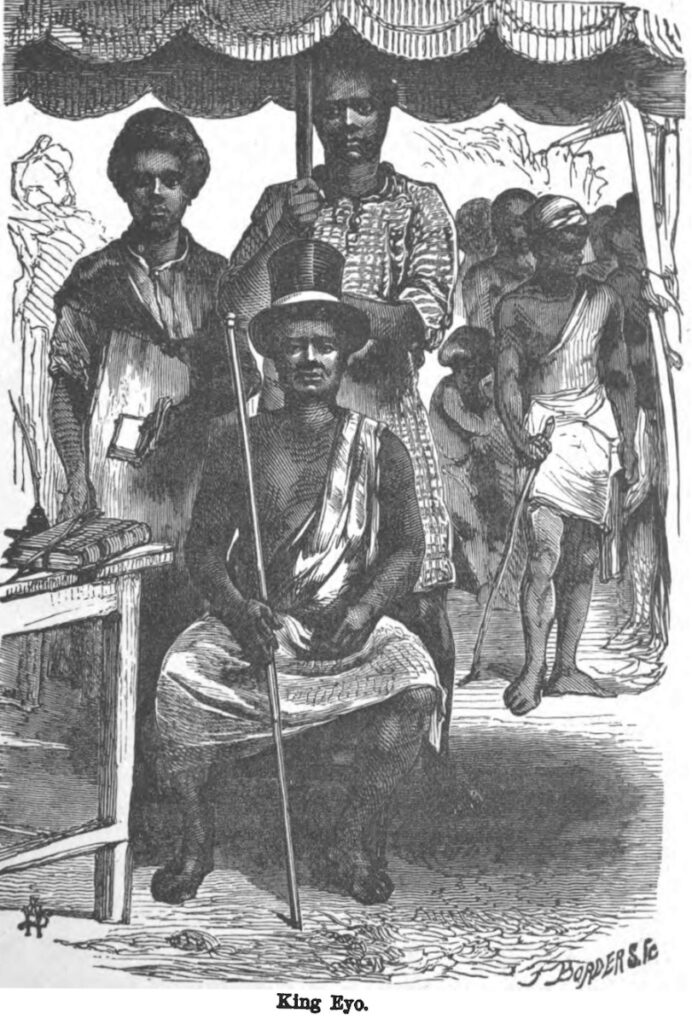

On a December morning in 1842, King Eyo Honesty of Old Calabar penned a letter to Commodore Raymond of the British Navy. In the letter, the King laid out conditions that the British Crown had to fulfill to enable him to end the slave trade in his territory. King Eyo further demanded some material objects, one of which was a piece of Indian cloth. He wrote, “I want…proper Indian romorle…I no want fool things.”[2] King Eyo’s insistence on a piece of Indian cloth as a condition for ending the Atlantic slave trade in his territory is a testament to the centrality of Indian textiles in the Atlantic trade and the value they had accumulated among elites in West Africa (Fig. 1).

In this article, I examine the relationship between the Atlantic trade in enslaved persons and the sartorial practices of mercantile and political elites in Bonny, Elem Kalabari (New Calabar), and Old Calabar, the three leading “slave ports” in the Bight of Biafra during the eighteenth century. The elites of these communities, located in present-day southern and south-eastern Nigeria, created a visual language using an assemblage of South Asian and European clothes and clothing accessories obtained via Atlantic and Indian sources onboard European ships to showcase wealth and power, and to propagate their societal norms and values. Beginning in the seventeenth century, the expansion of the Atlantic trade in enslaved persons provided elites in Bonny, Elem Kalabari, and Old Calabar with direct access to Asian and European textiles and clothing accessories, including English-style jackets and hats, coral beads, walking sticks, and smoking pipes. Despite the profound inequalities of the Atlantic trade, elite groups transformed these material goods into intricate assemblages that not only reaffirmed their wealth and power but also played a crucial role in mediating sacred ritual practices. Reframing how Bonny, Elem Kalabari, and Old Calabar elites remade textiles to forge a dynamically novel sartorial culture adds a crucial visual cultural dimension to the predominantly economic scholarly discussions of the Atlantic trade in the eighteenth-century Bight of Biafra.[3]

Between 1730 and 1850, the Bight of Biafra (hereafter “the Bight”) was the leading exporter of enslaved individuals to British merchants, accounting for approximately 13.7% of those forcibly transported to the Americas.[4] Captives taken from the Bight were exchanged for a variety of goods including guns, alcohol, metals, coral beads, and an array of textiles, the bulk of which were of Indian manufacture.[5] The vitality of South Asian textiles and British-style accessories in the Bight begs the question of how and whythese goods were adopted. While discussions of the slave trade often evoke narratives of displacement, loss, tremendous human suffering, and global inequality, scholars have increasingly emphasized the crucial role of that commercial system in cultural and sartorial transformations.[6] For an Atlantic society that never hosted European forts or permanent living stations like on the Gold Coast, the ensuing sartorial culture of elites in Bonny, Elem Kalabari, and Old Calabar was a consequence of a conscious sifting and selection of goods from across the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds.

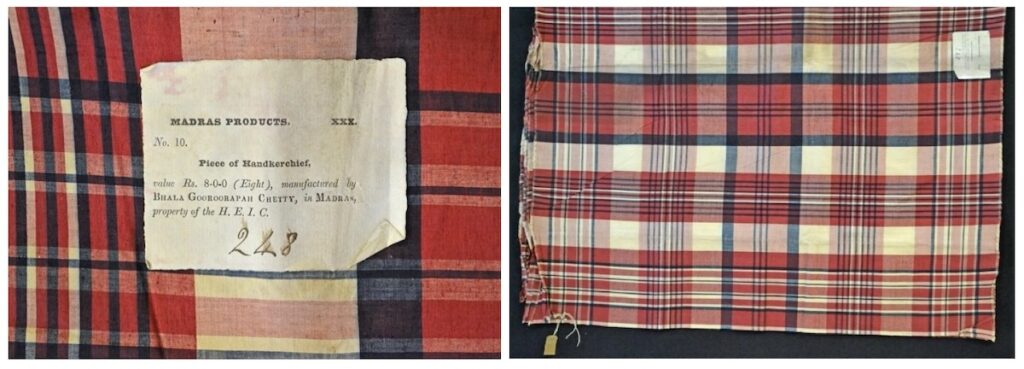

These mercantile elites selected only items deemed suitable for their trade and lifestyle, and for fashioning a dynamic sartorial culture that reflected their values and belief systems. For example, according to Kalabari folklore, the elites of Elem Kalabari chose the Indian madras because their goddess forbade the wearing of brightly patterned, flowery cloth.[7] The plaid pattern of the madras, with its laidback design, therefore suited existing belief systems, structuring both the aesthetic and economic aspects of the Kalabari elites’ relationship with madras cloth sold in the Bight by British merchants. This is one example of how the peoples of the Bight used imported goods from the Atlantic and Indian Oceans to mediate wealth, power, and ritual practices. These foreign textiles and fashion accessories transformed societies in the Bight but were also crucial in creating a sartorial modernity that was entirely driven by West African desires and cultural needs and aspirations. By highlighting the diverse Indian and Atlantic Ocean origins of textiles and fashion accessories in the Bight, together with the centrality of Indian textiles to the material expression of its elites, this article challenges assumptions of European cultural hegemony in the making of African Atlantic modernities. Furthermore, it contributes to discussions of how the Atlantic trade, beyond its tragic human cost and economic ramifications, transformed West Africa’s cultural practices, particularly in the spheres of clothing, power, and the materialization of ritual ceremonies.

Cloth, Prestige, and Power in the Bight of Biafra

The earliest known archaeological evidence of cloth in the Bight was discovered among sacred objects in burial sites presumed to be that of a king or an elite member of society dating back to the ninth and thirteenth centuries.[8] Important individuals were buried with piles of locally made cloth, sacred objects, and, in some cases, relatives or servants. It was believed that the most important “items” the deceased would need in the afterlife were revered objects, servants, and textiles. Therefore, before Europeans arrived in the Bight in the late fifteenth century, the wearing and possession of cloth were strictly regulated, as cloth served as one of the most visible indicators of identity, material wealth, and social status. In these societies, cloth functioned not only as a fabric to cover and protect the body but also as a material that expressed one’s individuality and the communal standing of the owner/wearer. This important function of clothing is expressed in the popular Bini proverb, ukpon a tue re do omo, which loosely translates to “the cloth one wears will determine the respect one is accorded in society.”

To maintain the power ascribed to cloth, kings and elites controlled the usage and distribution of textiles. In the powerful inland kingdom of Benin, located about 50–60 miles to the west of the Bight, the ability to own or wear cloth symbolized an important change in the status of the owner or wearer. For example, an enslaved domestic worker could not wear cloth unless permitted by her owner or the king. When permitted, the enslaved person was immediately recognized as a free person. Thus, an individual who could wear or own cloth was perceived to have been changed by the power of such fabrics. Referencing accounts of merchants who had visited the Benin kingdom, seventeenth-century Dutch writer Olfert Dapper described court rules according to which no one was allowed to appear before the Oba (the Benin King) without being clothed by him. In addition, young people went without clothing until they were married or whenever the Oba permitted them to wear cloth.[9] By controlling the use of cloth, the Oba exerted his power over his subjects, and cloth should therefore be considered as a symbol of political control and social stratification.

Despite the important role of cloth in the material expression of the peoples of the Bight, visual sources on the subject are scarce, partly because textiles were highly perishable in the region’s humid tropical climate. However, Benin’s famed bronzes provide clues to what constituted clothing in the early modern period.[10] A Benin bronze plaque dated to around the 1530s depicts two sword-wielding palace officials wearing what appears to be cloth tied over their lower bodies, with their heads, necks, wrists, and ankles wrapped in coral bead hats, necklaces and bracelets (Fig. 2). This ensemble of cloth worn and accessorized with coral beads has remained a staple in the dress cultures of various nations in the Bight today.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans and the dawn of the Atlantic trade on the West African coast, an intricate thriving network of textile production and trade existed. Cloth made from the fibers of plants such as cotton, raffia, hemp, palm trees, and tree barks were woven and distributed through ancient trade networks from the savanna to the hinterlands and down to coastal communities.[11] In the Bight, coastal communities in Bonny, Elem Kalabari, and Old Calabar exchanged their salt, sea harvest, and agricultural produce for cloth and other goods from the Benin kingdom and from eastern Igbo groups. Being a large influential kingdom, Benin was a superregional hub for commerce where different nations exchanged goods and services. Yoruba and Nupe artisans made textiles and traded them extensively with Benin merchants in return for Benin brass, peppers, palm oil, and agricultural produce. Two types of indigo-dyed strip cloth called iketa and ikirin were produced specifically for the Benin kingdom. In some parts of Yorubaland, the ikirin was also referred to as aso-ado, which translates to “Benin cloth.”[12] These textiles were traded extensively with groups further south of Benin. Moreover, in the absence of evidence of cloth production among the coastal communities, it seems likely that they depended on their inland neighbors for clothing through trade, which increased the visibility and value of cloth, exceptionally so among the groups in Bonny, Elem Kalabari, and Old Calabar situated to the southeast of Benin, near the Atlantic coast. Cloth as a commodity gained from bartering other goods became wealth to be hoarded and treasured by the elites of these nations.

Building on these earlier historical contexts of cloth acquisition and exchange in the Bight, we can recognize cloth as a powerful medium imbued with intricate social, political, and economic values—capable of transforming individual fortunes while reinforcing entrenched social hierarchies. Cloth was therefore a tool for political control and stratifying society, as much as it was a currency for exchanging goods and services prior to the arrival of Europeans on the Atlantic coast.

Historical Continuities and Transformations

When the Portuguese reached the Bight in the latter part of the fifteenth century, they followed the existing cloth trade routes and acted as distributors of locally made textiles. The earliest known European written account of the region comes from Portuguese trader Duarte Pacheco Pereira (1460–1533), who documented his first visit to the Benin kingdom in 1487.[13] Pereira reported buying cotton cloth in Benin, which he and his crew used to clothe enslaved persons and make awnings for their ships. Bastiam Fernandez, another Portuguese trader, bought about 1,816 textiles from the Forcados River near the Benin kingdom in 1505.[14] When the Dutch subsequently entered the West African trade, they bought and exported pieces of “Benin Cloth” to the Gold Coast. Dutch merchants described the cloth they purchased as a strip two yards by three yards, dyed in a plain indigo blue, a description that matches the ikirin and iketa cloth produced by Yoruba artisans.[15] The Dutch bought about 16,000 pieces between 1644 and 1646, as these “Benin Cloths” were held in high esteem along the Gold Coast and were consequently exchanged for gold.[16] The existence of such extensive cloth production and expansive trade networks within and outside the Bight before the arrival of Europeans demonstrates that cloth was not a novel or scarce commodity.

In the late fifteenth century, just as the Portuguese were beginning to establish a presence in India, Portuguese merchants introduced Indian textiles to the Bight through a system of gift diplomacy whereby merchants presented exotic gifts to the kings and rulers before the commencement of trade.[17] In 1505, the Portuguese trader Fernandez presented about 249 yards of different types of Indian textiles to the Oba, and, in that same year, King Manuel of Portugal sent a batch of gifts to Benin which included Indian beads, a piece of printed Chintz, a taffeta and white satin, six linen shirts, and a shirt of blue Indian silk.[18] When other Europeans arrived, they followed this system of gift diplomacy, a practice that outlived the slave trade into the period of “legitimate” commerce when cash crops exports superseded and eventually replaced the sale of captives. The Portuguese not only directly connected the African Atlantic with the Indian Ocean worlds, but presented gift items which included highly regarded varieties of Indian textiles to local Biafra and West African kings and elites as part of the gift diplomacy system of trade. Indian textiles therefore entered the Bight as luxurious items suitable only for kings, chiefs, and elite persons.

Indian cloth held a particular appeal in the Bight, as its availability within the region was not constant. All who had access to the cloth, including kings and emissaries, had to wait for the European ships that arrived about three to four times every year at the most to obtain Indian textiles. This scarcity further incentivized the perception of Indian fabrics as a source of wealth and an object of aspiration. Scarcity triggered internal demand, which in turn reinforced both the commoditization of Indian textiles in the Bight and their ability to signify status. A standardized valuation system linked the price of enslaved individuals to the cost of Indian textiles. For example, in 1526, fifteen human captives were sold for two and a half pieces of red cloth, and another fifteen for 300 yards of Indian cloth to Portuguese merchants.[19] Between the 1480s, when Indian textiles were first introduced through gift diplomacy, and the 1520s, when they became a standard unit of valuation in the slave trade, these fabrics evolved from symbols of political power and elite status to instruments of economic influence. Although Indian textiles became commodities used in the Atlantic trade by the early sixteenth century, usage and distribution largely remained within elite circles.[20] As varieties of Indian cloth were confined to elite circles and were perceived as textiles suitable only for kings and elite individuals, their usage and distribution were politically controlled.

Dapper noted in the mid-seventeenth century that European traders met the Benin king sitting under a canopy of Indian silk; that no one but the King was allowed to wear Indian textiles during ritual ceremonies; and that only members of the royal household had permission to adorn themselves with these foreign textiles.[21] This early status as luxurious elite gifts immediately elevated Indian textiles above locally available cloth, as the elites donned them for daily and ceremonial purposes while restricting their usage. The ways in which Indian textiles were introduced and utilized—as regalia fit only for kings and elites and worn during revered ritual ceremonies—imbued them with the potential to ascribe power to their wearers and owners.

In this context, Indian cloth had been transformed into a valuable object that became a conduit for transporting sociocultural beliefs that were and are palpable, and visible.[22] In the Bight, existing beliefs regarding local textiles as objects that had the potential to confer power on owners and wearers were projected onto the newly introduced foreign cloth. As a result, over time, they became treasures that elites hoarded and used as an affirmation of class and political status.

Indian Cloths in the Bight of Biafra Trade: Internal Demand, External Supply

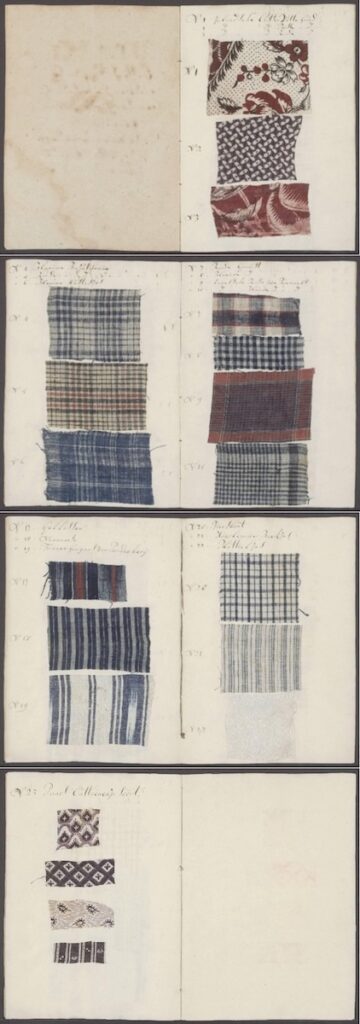

The Indian textiles sold in West Africa encompassed a diverse range of textures, from luxurious silk and fine linen to coarse cotton, often featuring bold or understated plaid designs. Collectively, these fabrics were known as “Guinea Cloth” or “Guinea Stuffs” (Fig. 3). [23] Indian textiles were often accompanied on ships involved in the transatlantic slave trade by European woolens, linens, and cotton fabrics, as well as European imitations of Indian textiles, strategically traded to meet diverse market demands. Among the diverse textiles sold in the Bight, Indian madras—a checkered cotton cloth also known as romorle, handkerchief, or Real Madras Handkerchief (RMHK)—emerged as a powerful cultural force. It shaped elite fashion preferences, served as a tool of political influence, and expanded the repertoire of material goods used in ritual practices.

As the demand for New World goods grew alongside the demand for enslaved people, the small riverine villages southeast of Benin unified into powerful kingdoms that controlled the three busiest slave ports in the Bight: Bonny, Elem Kalabari, and Old Calabar. Since Indian textiles were already established as objects with political and economic value in elite circles, and were used for ceremonial and ritual purposes, these cotton textiles became the most in-demand items at major trade ports in the region in the eighteenth century. British merchants initially attempted to foist English linens and woolens on traders of the Bight, but like the Dutch and the Portuguese before them, they soon discovered that Indian textiles held a special appeal for elites of the region.

In order to meet the demand for Indian textiles, English merchants stationed agents in major sites of cloth production in India, such as Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras. Through the East India Company (EIC), which was established in 1600 to control English trade in Southeast Asia, British agents acquired textiles in bulk quantities, shipped them to England where they were auctioned to the Royal Niger Company (RNC) and private businesses, which then re-exported them, in a final step, to West Africa.[24] By the late seventeenth century, British merchants were exporting large amounts of Indian cloth to West Africa. In 1688, the RNC exported 21,441 pieces of Indian cloth to West Africa, outnumbering the 10,838 pieces of English textiles the RNC exported to the region in the same year. The account books of William Davenport, a major investor in the Atlantic trade, further illustrate how internal demand for Indian textiles was crucial to the growth of the slave trade in the Bight. On average, Indian textiles made up one third of a ship’s textile cargo, closely followed by Manchester textiles. In 1761, a Davenport ship named the Tyrall sailed to Old Calabar with the exact types of Indian textiles that were most in demand by traders of the region.[25] For these textiles and other goods, the Tyrall ferried 461 enslaved persons to Havana from Old Calabar.

As the slave trade expanded, so too did the number of enslaved persons and Indian textiles per ship cargo. By the 1790s, Indian cloth made up about 40–60% of goods destined for the Bight. In 1792, two Liverpool ships sailed to Old Calabar with a cargo containing over sixty percent of Indian textiles.[26] That same year, British slave ships carted away an estimated 1,652 enslaved persons from Old Calabar, 2,379 from New Calabar, and 8,735 from Bonny.[27] When compared with previous years, the figures from 1792 marked some of the highest numbers of Indian textiles sold in the Bight, which corresponded with the thousands of enslaved persons taken from the region. In the eighteenth century, internal demand for Indian textiles and the prompt external supply of these textiles were at the heart of the slave trade in three of West Africa’s most important slave ports.

Despite the vast array of cloth imported into the Bight, specific Indian textiles such as calicoes, baftas, chintz, chelloes, necanees, photaes, and romals (also called Real Madras Handkerchiefs) were some of the constant names seen across hundreds of ship logbooks and in correspondences between traders of the Bight and British slave ship captains. British merchants carefully chose the textiles destined for the Bight to meet the taste of traders in the region, illustrating the sway consumers in the Bight exercised over the trade. When Patrick Black, a partner at William Davenport & Co., retired in the 1770s, he had to teach the new traders how to choose Indian textiles for Old Calabar.[28] Over time, the specific designs and colors demanded by traders of the Bight came to be named after towns in the region, such as the popular Bonny Blue Romal, Abang Romal, and Callabar Red (Fig. 4).[29]

The meticulous selection of Indian textiles destined for the Bight shows that African traders were consequential in shaping the commodities sold during the Atlantic trade, with the agency to accept or reject goods deemed unsuitable for their lifestyle and trade. Traders of the region were particularly vocal about their desire for certain Indian textiles. In a 1773 letter sent to a Liverpool merchant Captain Ambrose Lace, Grandy King George of Old Calabar, writing in old Pidgin English, requested, among a long-detailed list of items, Indian textiles. He wrote, “I want … one Chints for me of a hundrerd yard. I neckonees of one hundrd yards 1 photar of a hundrd y’s 1 reamall 1 hund. yards one cushita of a hundred yds one well bafts of the same.” In plain English, Grandy George demanded a hundred yards each of chintz, necanees, photaes, romals, cushtaes, and baftas. Robin John Ephraim, another Old Calabar trader, insisted on getting “2 Gun for every Slave I sell or 2 or 3 fine chint for myself and handkerchief.” [30] Grandy George and Robin John were not outliers but were typical in their demand for certain Indian textiles. This privileging of Indian textiles over other kinds of fabrics was shaped by their evolving sartorial and cultural adaptation among elite groups in eighteenth-century Bight of Biafra.

Continuous high demand for enslaved individuals in the Americas fueled the expansion of the slave trade in the Bight. To meet European demand for captives, elite trading families expanded to absorb more members into their ranks, including free men within and outside their societies as well as domestic slaves.[31] In turn, expansion of trade and increase in the number of traders facilitated the unprecedented availability of Indian textiles to a larger number of traders in the region. In addition to trade, Indian cloth circulated in the Bight through gifting, as traders gave these exotic textiles to their immediate relatives, extended kinsfolk, and neighbors.[32] With ownership of Indian textiles soaring among elite traders and their kinsmen, the old beliefs that had been projected onto them in elite circles were reinforced by a wider section of the population. Indian textiles thus had the power to transform traders outside of elite circles into rich and important persons in their societies. Consequently, over the course of the eighteenth century, Indian fabrics simultaneously functioned as luxury items, sacred textiles used for ceremonial purposes, a source of wealth, and currency in the slave trade.

The diary of an Old Calabar trader, Ntiero Edem Efiom, also known as Antera Duke, provides a window into life and trade in Old Calabar between 1785 and 1788. In total, Duke recorded thirty-eight slave ships that docked at Old Calabar, and an estimated 8,545 enslaved persons taken away in those ships.[33] However, but for a single entry where Duke was “dashed” four handkerchiefs (plaid madras), he does not mention the type of goods he and other traders received for their captives.[34] An account of Captain John Potter of Dobson and Fox rectified this omission in Duke’s diary.[35] Captain Potter noted that in a single transaction, when Duke sold 50 captives (22 men, 18 women, 5 boys, and 5 girls), he received the usual variety of goods: textiles, firearms, gunpowder, bar irons, manillas, copper, and brass rods. Indian textiles, however, constituted one third of the goods that Duke received, the largest of which was 540 yards of romals, 400 yards of cushtaes, 373 yards of photaes, 164 yards of chintz, 340 yards of necanees, and 38 pieces of Guinea Cloth. The fact that one third of the goods Duke received from a single transaction were Indian textiles highlights the simultaneous cultural and economic influence of Indian cloth in the Bight. When we compare Duke’s goods with the requests of Grandy George and Robin John, we see how internal West African demand for these textiles fueled the Atlantic trade and shaped the material life of traders in the region.

Sacred Cloths, Prestige, and Mediation

Beyond trade, within communities of the Bight, Indian textiles were adopted as material for mediating life cycle events. For example, when a girl came of age, her father presented her with pieces of the madras cloth. At the birth of a new baby, a woman’s husband was obliged to gift his wife with pieces of Indian madras. The funeral bed of deceased family members was often decorated with Indian textiles, and deceased people were typically buried with South Asian cloth. We see glimpses of some of these cultural uses of Indian textiles in Duke’s diary. In a January 1, 1788, entry, Duke wrote, “I made my girl, Archibong Duke’s son’s sister, wear a cloth for the first time and be a woman.”[36] In yet another entry on March 21, 1786, Duke noted that his wife’s brother died and was buried with 8 yards of fine cloth.[37] Some of the uses of Indian cloth described by Duke have continued into contemporary times, as captured in rare photographs of a lying-in-state room published by Joanne Eicher in which the funeral bed is covered with layers of Indian madras hanging from floor to ceiling (Fig. 5). Burying a relative with textiles served not only to present the deceased with important items they would need in the afterlife, but also to connect their spirit with that of the ancestors who were buried in a similar manner.[38] The sheer quantity of the madras displayed in the room is proof of the deceased’s status and wealth, and of the cultural value of the cloth among the modern Kalabari people.

Beyond their ritual symbolism, Indian textiles served as essential tools for navigating a cultural landscape increasingly shaped by English traders. Wearing foreign cloth and accessories became a strategic means of asserting status, influence, and adaptability in this evolving transactional space. Most importantly, it signified belonging to a closed group of elite men, rulers, and traders with access to European goods. When traders of Old Calabar met with English traders, they wore English-style clothes to signal a commercial kinship as well as to highlight their belonging to the elite group of local merchants. When meeting with Europeans, they changed to full European-style clothing, a strategically performative gesture designed to eliminate difference and gain favors in their trade transactions. Duke’s May 26, 1785 entry stated that he and two others “dressed as white men” to meet with Captain Comberbach.[39] The action of Duke and his fellow traders connotes an understanding of the importance of using clothing in an instrumental way to momentarily dissolve cultural difference and signal an ethos of belonging, reflecting what Jeremy Prestholdt described as the concept of similitude.[40] Similitude in the case of Duke and other merchants of the Bight was, of course, about not just sartorial visuals but also the deeper strategic aspiration embedded in self-fashioning. Local merchants of the region employed the textiles and clothing they accessed through the Atlantic trade to influence British merchants while also changing the meanings attached to the clothing within their own societies. However, when not meeting with Europeans, they dressed in what Duke described as “town style,” consisting of a mix of “long cloth and Ekpe cloth and hat and jacket and every fine thing.”[41]

About eighty miles from Calabar, the Bonny ruler, King Pebble did not change his clothes when meeting with British traders. He instead walked on yards of Indian cloth on his way to visit a British slave ship. While onboard the ship, British merchants hosted King Pebble at dinner; and because they understood the relationship between power and Indian textiles in Bonny, they dressed the dining table with yards of fine Indian cloth.[42] These contrasting uses of Indian textiles are indicative of the power of the Atlantic trade in shaping the everyday expression of elite traders in the Bight. Whether in relation to Europeans or within their communities, elites of the Bight wielded Indian cloth and other foreign accessories as a tool of both an exclusivity manifest in access to European goods, and inclusivity by using them to express belonging to the group of elite traders and political rulers in the Atlantic community of the eighteenth century. In essence, King Eyo’s insistence on a piece of “proper Indian romorle” underscores the high cultural significance of Indian textiles to the wealth, power, and identity of elites in the Bight. For these mercantile and political elites, Indian textiles became a symbol not only for articulating wealth, power, and ritual ceremonies, but also for expressing shared belonging and a unique modernity—a self-fashioned identity crafted through the accumulation of goods from the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds.

Conclusion

Elite traders from Bonny, Elem Kalabari, and Old Calabar were active participants in the Atlantic slave trade. Despite the inherent inequalities of the commerce, they developed vibrant sartorial cultures, selecting goods from across the globe that aligned with their values and belief systems. These goods shaped their societies and influenced the Europeans from whom they were sourced. The traders viewed the Atlantic trade as an opportunity to strengthen their kingdoms and to enhance their access to certain kinds of material culture, incorporating specific Indian textiles and English-style accessories. Rather than a straightforward adoption of European customs, or Europeanization, the sartorial practices of the Bight Atlantic represented a fusion of old and new ideas about cloth and entailed the invention and evolution of new meanings and functions for imported Indian textiles. Cloth had long been seen as a powerful material capable of altering an individual’s fortunes. These elites transferred this belief onto newly introduced items, such as Indian textiles and English-style jackets, hats, and walking sticks. By crafting dress cultures that incorporated specific Asian and European goods, these elites not only asserted their agency in the unequal Atlantic trade system, but also used these goods to express individuality, reiterate wealth and power, and propagate their values throughout the period of the Atlantic slave trade.

Eguono Lucia Edafioka is a PhD Candidate in history at Vanderbilt University and a fiction writer

[1] This is a proverb by the Bini-speaking people of the Benin Kingdom illustrating the value of cloth in their culture.

[2] J. F. Johnson and British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, Proceedings of the General Anti-slavery Convention: Called by the Committee of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and Held in London from Tuesday, June 13th to Tuesday, June 20th, 1843 (John Snow, 1843), 261.

[3] For economic focused narratives of the slave trade, see Ugo G. Nwokeji, The Slave Trade and Culture in the Bight of Biafra: An African Society in the Atlantic World (Cambridge University Press, 2010); Toby Green, A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution (The University of Chicago Press, 2021); Paul Lovejoy and David Richardson, “‘This Horrid Hole’: Royal Authority, Commerce and Credit at Bonny, 1690–1840,” The Journal of African History 45, no. 3 (2004): 363–92, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853704009879 (all web links accessed March 27, 2025).

[4] Eltis David et al., eds., The Atlantic Slave Trade, 1527–1867: A Database (Cambridge University Press, 1999); and https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database. I generated this figure using data on the database.

[5] Marion Johnson, Anglo-African Trade in the Eighteenth Century: English Statistics on the African Trade 1699–1808 (Intercontinental,1990); Kobayashi Kazuo, “The British Atlantic Slave Trade and Indian Cotton Textiles: The Case of Thomas Lumley & Co.,” in Modern Global Trade and the Asian Regional Economy, ed. Tomoko Shiroyama (Springer Singapore, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0375-3_3.

[6] For memory and the slave trade, see Brempong Osei-Tutu, “Cape Coast Castle and Rituals of Memory,” in Materialities of Ritual in the Black Atlantic, ed. Akinwumi Ogundiran and Paula Sanders (Indiana University Press, 2014), 317–37; Cheryl Finley, Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon (Princeton University Press, 2018) and Andrew Apter, “History in the dungeon: Atlantic slavery and the spirit of capitalism in Cape Coast Castle, Ghana,” The American Historical Review 122, no. 1 (2017): 23–54. For cultural and sartorial transformations, see Ana Lucia Araujo, The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, 2023); Jody Benjamin, Texture of Change: Dress, Self-Fashioning and History in Western Africa, 1700–1850 (Ohio University Press, 2024); and Hermann W. von Hesse, “‘A Modest, but Peculiar Style’: Self-Fashioning, Atlantic Commerce, and the Culture of Adornment on the Urban Gold Coast,” The Journal of African History 64, no. 2 (2023): 269-91, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853723000294.

[7] Victor Erekosima and Joanne B. Eicher, “Kalabari Cut-Thread and Pulled-Thread Cloth,” in Global Trade and Cultural Authentication: The Kalabari of the Niger Delta, ed. Joanne Eicher (Indiana University Press, 2022), 20–28.

[8] Thurstan Shaw, Igbo-Ukwu; An Account of Archaeological Discoveries in Eastern Nigeria (Northwestern University Press, 1970), 15–45, 240–244; Graham Connah, The Archaeology of Benin: Excavations and Other Researches in and Around Benin City, Nigeria (Clarendon Press, 1975), 62–67, 236–37, 247–53.

[9] Olfert Dapper, cited in Henry Ling Roth, Great Benin: Its Customs, Art and Horrors (University of California Press, 1903), 24.

[10] For more on Benin art, see “Benin Bronzes,” British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/benin-bronzes.

[11] Colleen Kriger, Cloth in West African History (AltaMira Press, 2006), 21–28.

[12] Samuel. A. Akintoye, “The North-Eastern Yoruba Districts and the Benin Kingdom,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 4, no. 4 (1969): 539-53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41856778.

[13] Duarte Pacheco Pereira, Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis, trans. George H. T. Kimble (Hakluyt Society, 1937).

[14] A. F. C. Ryder, Benin and The Europeans 1485–1897 (Humanities Press, 1969), 37.

[15] Cf. K. Ratelband, Vijf Dagregisters van het kasteel São Jorge da Mina (The Hague, 1953), XCVII, quoted in Ryder, Benin and The Europeans, 94.

[16] A. F. C. Ryder, “Dutch Trade on the Nigerian Coast During the Seventeenth Century,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 3, no. 2 (1965): 203, http://www.jstor.com/stable/41971157.

[17] For more in-depth reading on gift diplomacy see Araujo, The Gift.

[18] Ryder, Benin and the Europeans, 41.

[19] Ryder, Benin and the Europeans, 63.

[20] Joseph E. Inikori, “English versus Indian Cotton Textiles: The Impact of Imports on Cotton Textile Production in West Africa,” in How India Clothed the World: The World of South Asian Textiles, 1500–1850, ed. Giorgio Riello and Tirthankar Roy (Brill, 2009), 85–114; John K. Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 48–50.

[21] Dapper, quoted in Roth, Great Benin: Its Customs, Art and Horrors, 83, 109, 111.

[22] Ann Smart Martin, “Makers, Buyers, and Users: Consumerism as a Material Culture Framework,” Winterthur Portfolio 28, no. 2/3 (1993): 141-57 https://doi.org/10.1086/496612.

[23] Stanley Alpern, “What Africans Got for Their Slaves: A Master List of European Trade Goods,” History in Africa 22 (1995): 5–43, https://doi.org/10.2307/3171906.

[24] Koyobashi, Indian Cotton Textiles, 129.

[25] Slave Trading Records from William Davenport & Co., 1745–1797, British Online Archives (Microform Academic Publishers, 2009).

[26] Trading Account of William Davenport, quoted in David Richardson, “West African consumption patterns and their influence on the eighteenth-century English slave trade,” in The Uncommon Market: Essays in the Economic History of the Atlantic Slave Trade, ed. Henry A. Gemery and Jan S. Hogendorn (Academic Press, 1979): 312–15. For more on the Davenport account, see Slave Trading Records from William Davenport & Co., 1745–1797, British Online Archives (Microform Academic Publishers, 2009).

[27] I generated these figures from my calculations using numbers on the Slave Voyages database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database.

[28] Stephen Behrendt et al., The Diary of Antera Duke: An Eighteenth-Century African Slave Trader (Oxford University Press, 2010), 56.

[29] John Adams, Remarks on the Country Extending From Cape Palmas to the River Congo, Including Observations on the Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants (G. and W. B. Whitaker, 1825), 254-55.

[30] Williams Gomer, “The Massacre at Old Calabar,”in History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letters of Marque with an Account of the Liverpool Slave Trade, 1744–1812 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004), 545–47.

[31] For more on impacts of the Atlantic trade on family structures in the Bight of Biafra, see G. I. Jones, The Trading States of the Oil Rivers (Oxford University Press, 1963), 105-50; K. O. Dike, Trade and Politics in the Niger Delta: An Introduction to the Economic and Political History of Nigeria (Oxford University Press, 1956), 19–46.

[32] Behrendt, The Diary of Antera Duke, 169, 197.

[33] Figure generated from the numbers recorded in Antera Duke’s diary.

[34] Dash is a Pidgin English word for gifting. To dash is to gift. Behrendt, The Diary of Antera Duke, 167.

[35] Trading Invoices and Accounts, Dobson and Fox, 1766, 1771, Davenport Papers, MMM; Dobson Calabar account, Hasell MS, Dalemain House, Cumbria, quoted in Behrendt, The Diary of Antera Duke, 61.

[36] Behrendt, The Diary of Antera Duke, 217.

[37] Behrendt, The Diary of Antera Duke, 177. Traders referred to Indian cloth as fine cloth. For more on this, see Richard Mather Jackson, “Journal of a Residence in Bonny,” Voyage to Bonny River on the West Coast of Africa (The Garden City Press Ltd, 1934), 77, 79.

[38] For more discussions on funeral practices, see Joanne Eicher and Tonye Erekosima, “Fitting Farewells: The Fine Art of Kalabari Funerals,” in Ways of the River Arts and Environment of the Niger Delta, ed. Martha Anderson and Philip M. Peek (UCLA Fowled Museum of Cultural History, 2022).

[39] Behrendt, The Diary of Antera Duke, 149.

[40] Jeremy Prestholdt, “Similitude and Empire: On Comorian Strategies of Englishness,” The Journal of African History 43, no. 1 (2002): 61–82, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20079420.

[41] Behrendt, The Diary of Antera Duke, 191; Ekpe cloth is also called ukara, a cloth made by the Igbo, further north of Old Calabar. Ukara is an indigo-dyed cloth designed with geometric patterns and animal symbols (nsibidi patterns) and worn by titled Ekpe members in Calabar. For more, see “Cloth (Ukara),” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/en-CA/objects/125936.

[42] Richard Mather Jackson, Voyage to Bonny River, 77–79.

Cite this article as: Eguono Lucia Edafioka, “The Indian Madras Cloth and Elite Self-Fashioning in the Bight of Biafra,” Journal18, Issue 19 Africa (Spring 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7815.

Licence: CC BY-NCJournal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.