Helina Gebremedhen

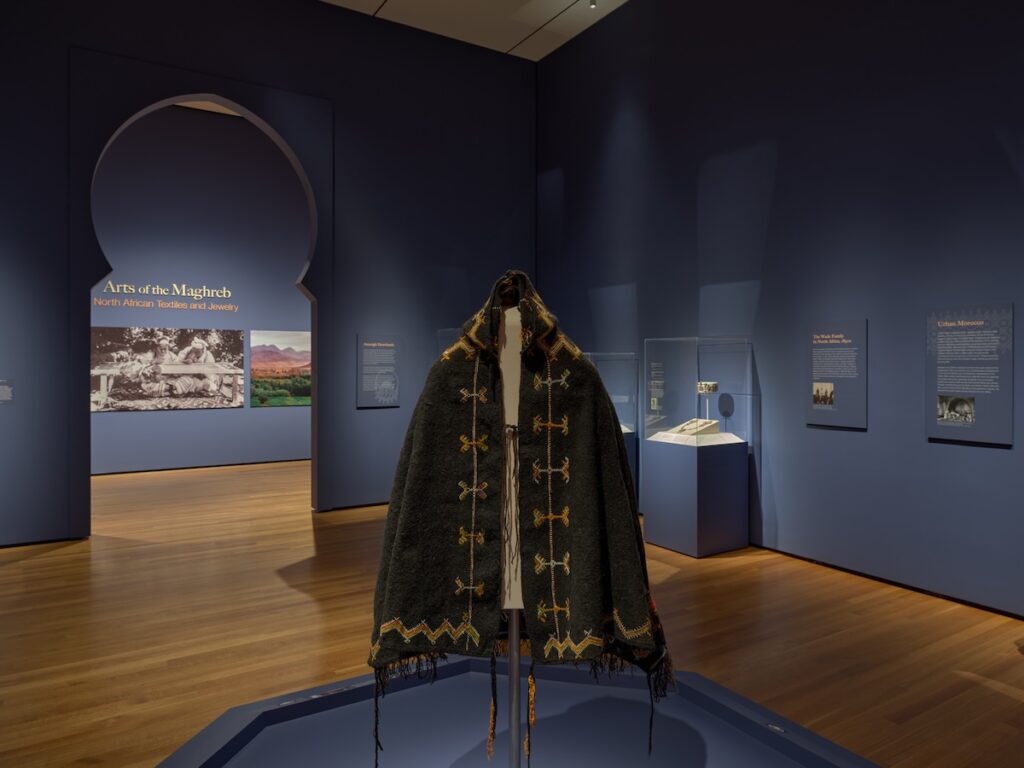

In November 2024, the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) inaugurated the exhibition Arts of the Maghreb: North African Textiles and Jewelry. The exhibition, on view through October 2025, highlights the rich artistic traditions of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, showcasing intricate textiles and exquisite jewelry drawn entirely from the CMA’s Permanent and Education Art collections (Fig. 1).[1] The thirty-nine artworks on view range from large format silks to delicate accessories, all exemplifying the specialized skills of North African artists—Amazigh and Arab, Muslim and Jewish—and the diverse aesthetics of their multifaceted communities.

The exhibition draws on the CMA’s specific holdings to present textiles and jewelry as integral to daily life in the Maghreb, showing how a multiethnic, multireligious, and multilingual society presented itself and shaped its surroundings. This emphasis on shared production and usage is a central curatorial choice in contrast to prevailing scholarly constructs that emphasize dichotomies of Arab vs. “Berber,” urban vs. rural, and Andalusian influences vs. local reception. It also challenges a singular, reductive narrative of historical incompatibility between Muslims and Jews, a dichotomy that continues to shape contemporary geopolitics, as some of the recent rhetoric surrounding the war on Gaza demonstrated. The exhibition therefore strives not only to highlight the beauty and history of a range of Maghrebi artworks, but also to demonstrate the importance of public-facing scholarly research that spotlights these rich, complex, yet often obscured histories.

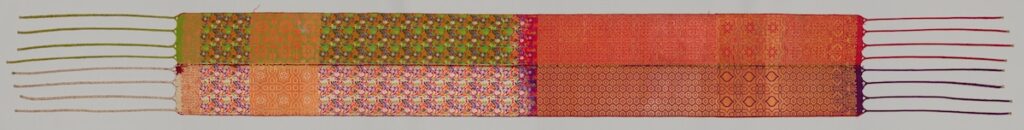

The exhibition is organized into four sections that thematize geography and space. At the entrance, a first vignette titled Amazigh Heartlands comprises the iconic silver-and-enamel jewelry of eastern Algeria’s indigenous Kabyle peoples. Additionally, a broad akhnif cloak characteristic of the Aït Ouaouzguit of southeastern Morocco, woven as a single piece on a complex vertical loom, serves as a focal point for both this grouping and the exhibition in general (Fig. 2). A subsequent display, Urban Morocco, showcases the iconic embroidery genres distinct to the cities of Fes, Chefchaouen, and Azemmour. Most notably, it is anchored by a hizam, a type of luxury belt made of silk lampas weave that is closely associated with workshops in the city of Fes; the CMA’s example bears six distinct designs, and its light creases suggest it was once worn (Fig. 3). Along the far wall, Tunisian Weavings showcases two exemplary textiles: an ornately assembled curtain panel and a sumptuous ‘ajar veil, the lower rows of the latter integrating mirrored Arabic calligraphy into the woven silk (Fig. 4). A final vignette, titled Cosmopolitan Algiers, assembles a series of gossamer tenchifa and beniqa headdresses embroidered by Jewish artisans using gold and silver threads alongside a series of fine gold- and gemstone-encrusted jewelry (Fig. 5).

Curatorial research into these little-studied artworks also uncovered additional narrative threads, highlighting for instance the role of CMA co-founder Jeptha Homer Wade II (1857–1926) and his wife, Ellen Garretson Wade (1857–1917), in shaping the museum’s North African collection. Their personal travels to the Maghreb in the 1890s led to the first gifts that established the CMA’s holdings in this region. The Cleveland Museum’s encyclopedic collection also facilitated cross-departmental collaboration. The display of Eugene Delacroix’s etching A Jewish Woman of Algiers (1833) adjacent to the Algerian textiles and jewelry sought to emphasize the contemporaneity of two genres that are rarely viewed alongside one another yet present two poles of nineteenth-century North African visual culture. While the print exemplifies the foreign artist’s Orientalizing gaze, the textiles and jewelry, by contrast, assert the artistry, skill, and aesthetic sensibilities of North African makers on their own terms (Fig. 6).

Several curatorial considerations underpinned this exhibition, which was initially rooted in a two-year comprehensive collections survey of the CMA’s North African holdings. As an introductory presentation of objects and a region that remained unfamiliar to many, didactic clarity was of utmost importance. Section panels and labels sought to provide key contextualizing information on the production and use of these objects, taking the opportunity to foreground self-representations through the use of emic terms like Maghreb, Amazigh, and Imazighen, instead of retroactively offering them as alternatives to better-known yet pejorative terminology rooted in European and often colonial scholarship. Large-format historical and contemporary photography, a custom map, and pronunciation aides also sought to render the exhibition accessible to many audiences, in addition to the fluid layout developed by Alyssa Arend, Exhibition Designer, and Mary Thomas, Senior Graphic Designer.

Institutionally, the exhibition is a cornerstone of a broader initiative led by Dr. Kristen Windmuller-Luna, Curator of African Arts, to challenge conventional boundaries in the field and firmly position the Maghreb as an integral part of Africa’s rich creative legacy. To date, much scholarly analysis approaches the Maghreb as a space physically demarcated (by the Sahara Desert) as well as socially and historically distinct from other African societies to the south. Dismantling these historiographic divides is especially well-suited to encyclopedic institutions: the CMAs renowned collection also includes strengths in classical West African sculpture, just one of many African regions with deep commercial and historical links to the Maghreb. Indeed, the CMA’s recent acquisitions, integrated permanent displays, and special exhibitions like Maghreb aim to expand this perspective, and continue to raise the profile of African arts with local audiences.

Helina Gebremedhen, a PhD candidate at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, was the Leigh and Mary Carter Director’s Research Fellow at the Cleveland Museum of Art from 2022-24

[1] The Cleveland Museum of Art includes the Education Art Collection (EAC), a parallel collection of over 10,000 artworks made available for greater access and handling in a range of museum programs, as well as for research and exhibitions. See: https://www.clevelandart.org/learn-with-us/education-art-collection (accessed March 15, 2025)

Cite this article as: Helina Gebremedhen, “Arts of the Maghreb: North African Textiles and Jewelry – Curatorial Reflections,” Journal18, Issue 19 Africa (Spring 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7767.

Licence: CC BY-NCJournal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.