Zulfikar Hirji

The ousting of the Portuguese from coastal East Africa in 1729 ushered in an era of cultural efflorescence in the Swahili Muslim city-states of Pate, Siyu, and Faza on Pate Island in the Lamu Archipelago.[1] At this time, each city-state had a population ranging in size from ten to twenty thousand people, many of whom lived in urban settlements.[2] Pate was the region’s maritime trading hub from where raw materials, manufactured goods, and people moved between Africa and the Western Indian Ocean littoral. The island’s population was diverse, comprising indigenous groups of different ethnic backgrounds, Muslims and non-Muslims, mainland migrants and settlers, as well as people from eastern Africa and the Western Indian Ocean, including those from Arabia and India.[3] It was also a vibrant center of Islamic scholarship and artistic production with significant architectural and manuscript traditions.

By the mid-1800s, however, the island’s fortunes waned. Pate’s harbor silted up and the city-state succumbed to internal conflicts and incursions by the Omani Bu Saidi empire, which had established a capital in Zanzibar and was fast taking control of East African coastal territory and trade. By the late 1800s, Siyu and Faza also came under Zanzibar’s suzerainty, bringing an end to Pate Island’s renaissance.

Scholarship on Pate Island’s pre-twentieth century material culture and that of coastal East Africa, more generally, has been limited and challenging, owing to its destruction, decay, and dispersal. The dearth of historical accounts about Pate Island has also contributed to a reduced understanding of its social and cultural life. For its part, Western scholarship has also obscured knowledge about coastal East Africa’s peoples and culture. For example, generalizing terms such as “African”, “Arab”, and “Swahili”, used to identify, categorize, and make sense of the diverse origins and histories of coastal East Africa’s peoples, have glossed over the complex ways in which coastal peoples self-identified and expressed themselves artistically. Moreover, scholarship has done little to challenge the racist European colonial-era view that the coast’s material culture, particularly that which relates to Islam, was produced by non-Africans or produced by Africans in a derivative or sub-standard manner. These and other enduring perspectives have dispossessed East Africa’s coastal communities of their contributions to Islamic culture and contributed to its decades-long neglect by scholars in various academic fields, including Islamic and African art history.[4]

Most studies of Pate Island’s material culture were undertaken between the 1970s and 1990s. These include studies by the Africanist James de Vere Allen, who advocated for the preservation of Pate Island’s material culture,[5] and those by Howard Brown, whose ethnographic research on Pate Island in the 1980s argued that Siyu was a crafts production center between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[6] Additionally, archaeological excavations and architectural surveys of Pate Island’s pre-modern settlements such as those by Mark Horton at Shanga, a site where the earliest mosque dates to around the eighth century, have provided an understanding of the island’s urban formations and the types of local and imported materials and products used in these settlements, including glass, ceramics, and textiles.[7]

The recent discovery of a dispersed and little-known corpus of some thirty highly decorated Qur’an manuscripts produced on Pate Island, datable to between ca. 1750 and ca. 1850, affords the possibility of a renewed look at Pate Island’s material culture and artisanry, and that of coastal East Africa more broadly.[8] Located in private and public collections in Kenya, Tanzania, Oman, UK, and the USA, the manuscripts are significant because they are, at present, the only known examples of Qur’ans from coastal East Africa and are part of a limited number of surviving Arabic manuscripts from the region.[9] This observation is put in relief when it is recalled that Islam has been on the coast, and on Pate Island in particular, since the eighth century.[10] When compared with Qur’ans produced in areas that Pate Island likely had contact with—such as Somalia, Ethiopia, Oman, Yemen, Iran, and India—Pate Island’s manuscripts are stylistically distinctive. And when the manuscripts are compared with objects produced in different media from Pate Island, there are striking similarities. This essay presents a few examples of this type of transmediality and proposes that they evidence the active production of a Pate Island style.

Decorated Qur’ans

The corpus, at present, comprises some thirty complete or partial Qur’ans. There are single volume, two-volume, and four-volume Qur’ans. Some have colophons with scribal signatures and dates of completion, endowment inscriptions, and ownership notations. Many include commentary in Arabic and supplementary sections containing prayers. The manuscripts’ shared material features include: the use of European-made laid paper, some traceable to Northern Italy; inks colored black, red, yellow, brown, and green; and blind-stamped leather covers. Codicological analysis indicates that they were produced by skilled artisans who knew how to calculate the quantity and size of paper required for a single volume or multiple volumes; prepare the paper for writing; make ruling-frames and impress paper with rule lines; prepare and use medium-appropriate inks and fixatives; prepare and use reed pens for writing; bind the completed sheets into a text block; and produce decorative blind-stamped leather covers for the manuscripts.

Swahili poetry composed during the time the Qur’ans were made describes some of these production processes as well as the purchase of paper, inks, and materials to produce a ruling frame, and the aesthetics of penmanship. This documentary information and evidence derivable from surviving manuscripts provide clues on how the Qur’ans were made.

However, much remains to be understood about the manuscripts’ scribes and artists, including when and how they learned their craft, how they transmitted and honed their knowledge and skills, who supported the costs of their materials and labor, and their artistic milieu.

The manuscripts’ Qur’anic text is mostly written in a local script that resembles a calligraphic style known as naskh. It also includes some text that resembles the style known as thuluth. More ornamental calligraphy and decorations in the forms of geometric and vegetal motifs are reserved for frontispieces, select chapter headings, basmalas (invocations of God), division and prostration markers, and supplicatory sections. The manuscripts’ decorative programs are not identical but have family resemblances. Such decorative variation suggests that scribes and artists had artistic freedom and were not working from a template. Nevertheless, commonality in terms of calligraphic style, sections selected for decoration, the mise en page (layout), and motifs suggests that artists were drawing from a shared visual repertoire and working within an established or desired aesthetic.

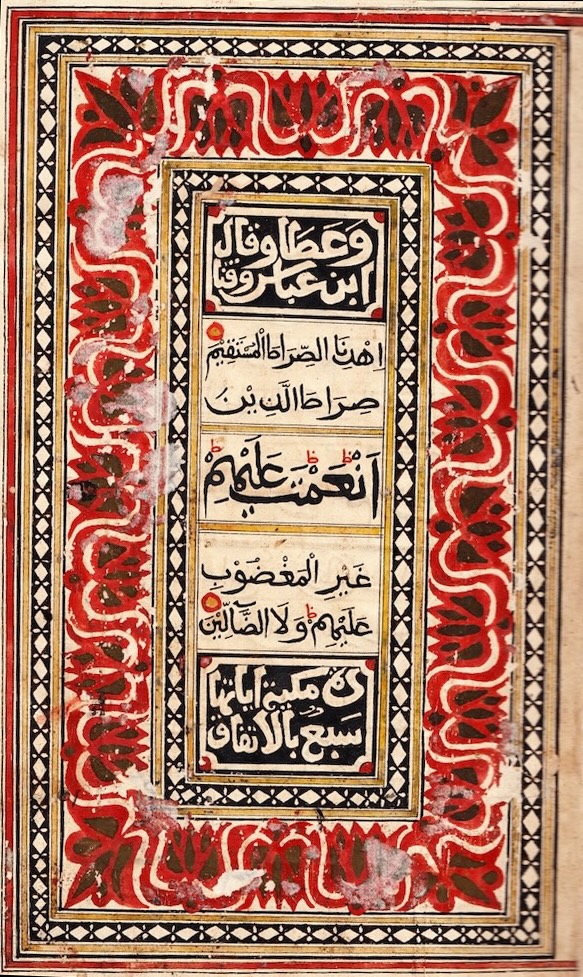

The argument for the establishment of a local style is more compelling when the manuscripts are compared with local material culture produced in other media. For example, manuscript decorations of scrolling floral and vine motifs and geometric patterns closely resemble those found on intricately carved stucco walls of Pate Island’s domestic and mosque architecture. The scrolling lotus-like pattern on the frontispiece of a nineteenth-century Qur’an copied in Siyu (Fig. 1) is identical to those found on a stucco-carved wall and niche frame in a nineteenth-century house on Tundwa on Pate Island (Fig. 2), similar examples of which are found throughout the Lamu Archipelago.[11] That such niches are thought to have been used to display or store precious objects, including Qur’ans, suggests another way in which these manuscripts were put into conversation with Pate Island’s architecture.

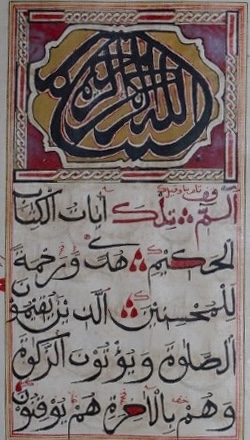

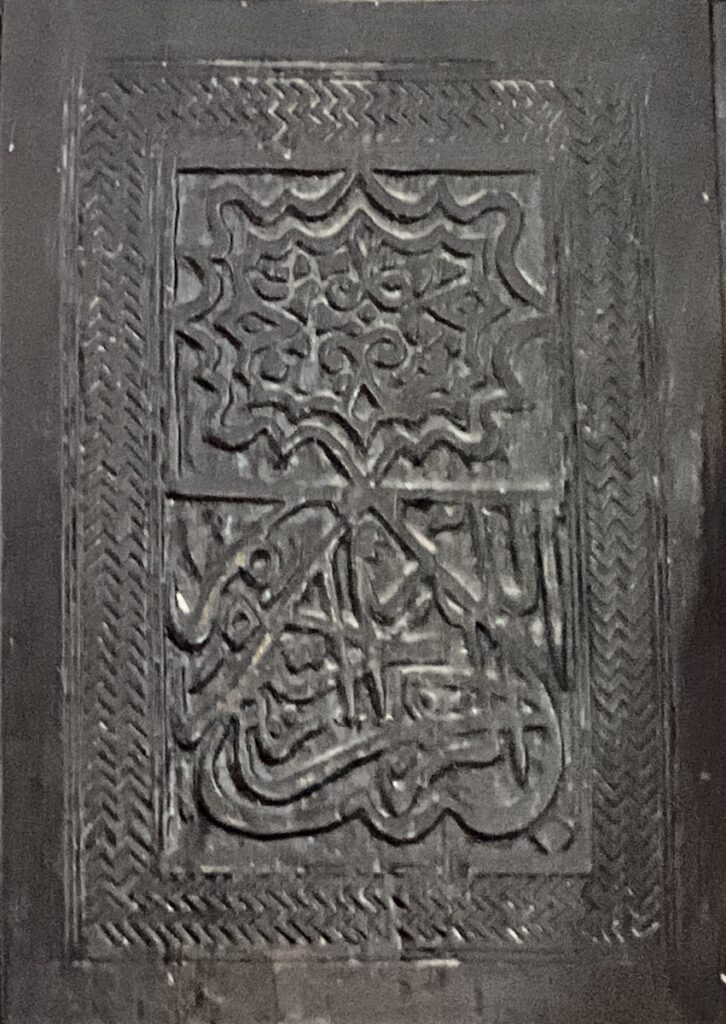

Another example of transmediality is the striking correspondence between the decorative basmalas found in a Qur’an completed in the mid-1800s in Faza (Fig. 3) and a basmala carved on a signed, undated (possibly nineteenth century) wooden minbar in Faza’s Friday Mosque (Fig. 4). The minbar also includes carved intertwined s-shaped framing motifs that resemble those in the manuscript, and there is strong similarity between the naskh-like script used in the Qur’ans and the script used in the minbar’s inscriptions (Fig. 5).

Conclusion

These are but a few examples of the many ways in which Pate Island’s Qur’anic corpus shares a visual style with other local objects. Such transmedial connections suggest that artists working on manuscripts were drawing upon an established style or contributing to its formation. It may be that these artists were part of a school, workshop, or guild, or under common patronage. If confirmed, such possibilities would begin to explain the stylistic congruency between the island’s diverse material culture. Taking into consideration Pate Island’s established land and maritime trade networks in Africa and the Indian Ocean, it is worth asking why its artists did not simply reproduce styles that came from beyond their shores or produce pastiche-like objects that would make visible their trading prowess or purchasing power.

One answer may lie in the practices of Pate’s textile makers, who in the pre-Portuguese period are thought to have unraveled Gujarati and Chinese silks and woven their threads into cloth that satisfied local tastes.[12] Like them, in the face of the foreign and faraway, Pate Island’s renaissance-era artists may have sought to forge a distinctive style using a local aesthetic, thereby distinguishing the island’s artistic production from what was produced elsewhere.

Zulfikar Hirji is Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at York University in Toronto, CA

[1] James de Vere Allen, “Swahili Culture Reconsidered: Some Historical Implications of the Material Culture of the Northern Kenyan Coast in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Azania 9 (1974): 105-38.

[2] George Abungu, “Pate: A Swahili Town Revisited,” Kenya Past and Present 28 (1996): 51; W. Howard Brown, “History of Siyu: The Development and Decline of a Swahili Town on the Northern Kenya Coast,” (PhD Thesis, Indiana University, 1985), 34-35, 119-21 (n. 32), 205.

[3] Randall Pouwels, “Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean to 1800: Reviewing Relations in Historical Perspective,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 35, nos. 2-3 (2002): 419-22.

[4] Adria LaViolette and Stephanie Wynn-Jones, “The Swahili World,” in The Swahili World, ed. Adria LaViolette and Stephanie Wynn-Jones (Routledge, 2018), 1-6; Prita Meier and Allyson Purpura, “Provocation from the Coast: Toward a Networked History of Swahili Coast Arts,” in Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, ed. Prita Meier and Allyson Purpura (Krannert Art Museum and Kinkead Pavillion, 2018), 17-18; Patricia Bentley and Zulfikar Hirji, “The Dialogic Exhibition,” in Made for the Eyes of One Who Sees: Canadian Contributions to the Study of Islamic Art and Archaeology, ed. Marcus Milwright and Evanthia Baboula (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022), 365–71; Zulfikar A. Hirji, “Dispersal, Decolonization, and Dominance: African Muslim Objects from the Sultanate of Witu (1858-1923),” in Decolonizing Islamic Art in Africa: New Approaches to Muslim Expressive Cultures, ed. Ashley Miller (Intellect Books, 2024), 21–54.

[5] James de Vere Allen, “Swahili Ornament: A Study of the Decoration of the 18th Century Plasterwork and Carved Doors in the Lamu Region,” Art and Archaeology Research Papers 3 (1973): 87-92; James de Vere Allen, “Swahili Book Production,” Kenya Past and Present 13 (1981): 17-22.

[6] Howard Brown, “Siyu: Town of the Craftsmen: A Swahili Cultural Centre in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries,” Azania 23 (1988): 101-13.

[7] Mark Horton, Shanga: The Archaeology of a Muslim Trading Community on the Coast of East Africa (London: British Institute in Eastern Africa, 1995), 222-23, 407-28; Thomas H. Wilson and Athman Lali Omar, “Archaeological Investigations at Pate,” Azania 32 (1997): 31-76; Usam Ghaidan, Lamu: A Study in Conservation (East African Literature Bureau, 1976), 30-42.

[8] Simon Digby, “A Qur’an from the East African Coast,” Art and Archaeology Research Papers 7 (1975): 49-55; Walid Ghali, “The Making of a Qur’an Manuscript in Lamu Archipelago: The Indian Ocean Cross-cultural Influence,” in Muslim Cultures of the Indian Ocean: Diversity, Pluralism Past and Present, ed. Stéphane Pradines and Farouk Topan (Edinburgh University Press, 2022), 40-57; Zulfikar Hirji, “A Corpus of 18th–19th Century Illuminated Qur’an Manuscripts from Coastal East Africa,” Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 14 (2023): 356-95.

[9] Anne K. Bang, “Arabic-language Manuscript and Print as a Source for Indian Ocean Islamic History: The Case of East Africa,” History Compass 20, no. 7 (2022): e12713.

[10] Horton, Shanga, 200-8.

[11] See, for example, Ghaidan, Lamu, 18: Fig. 1–14; 29: Fig. 1–25.

[12] Jeremy Presthold, “Swahili Polities and the Continental-oceanic Interface,” in The Swahili World, ed. Adria LaViolette and Stephanie Wynn-Jones (Routledge, 2018), 519.

Cite this article as: Zulfikar Hirji, “Forging Swahili Muslim Style: Material Culture from Pate Island (ca. 1750-ca. 1850),” Journal18, Issue 19 Africa (Spring 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7729.

Licence: CC BY-NCJournal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.