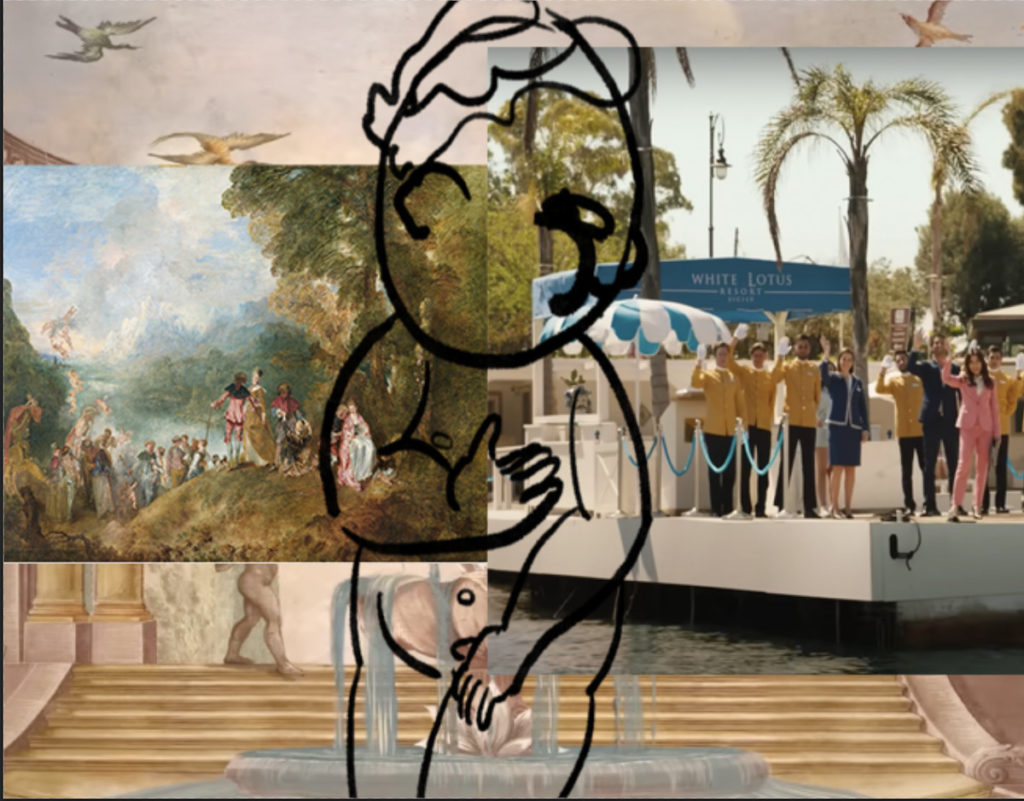

The distinct theme song of Mike White’s TV hit The White Lotus (WL) returned to screens around the world this past winter. This time, the opening credits paired Cristobal Tapia De Veer’s warbling sounds with a pastiche of rococo wallpaper: fountains gushed, putti and satyrs romped in a pastoral eighteenth-century landscape full of ruins and erotic intrigue. The show’s second season brought audiences to yet another magical island resort—now in Sicily. In keeping with the rococo motifs of the credits, the Italian hotel was decked out with porcelain turquerie busts, mirrors, and other nods to eighteenth-century décor that dovetailed with repeated shots of foamy waves washing up against rocky cliffs (the tensions of love adrift!). The prominence that White gave to the recycling of rococo motifs poses the query: Is the rococo back? And if so, how (and why) does it offer an apt aesthetic for commenting on social relations among the elite and elite-adjacent today?

As this essay will explore, the island premise of the show and its aesthetic sensibilities appear to re-hash rococo precedents, transposing certain tropes to the present. The so-called rococo style developed in the context of shifting social hierarchies and the emergence of a new market culture of commodities. The art of “tact” served as a means of negotiating social relations in this changing landscape of new goods and economized desires. In an aesthetic parallel, tactful artfulness provided a means of self-presentation (and self-understanding) that embraced and mediated a world of commodified relationships. Ewa Lajer-Burcharth has shown how the French painter François Boucher’s work, in particular, can be understood as a paradigmatic demonstration of these types of aesthetic mediations between art, commodity, and the practice of making others comfortable in order to advance one’s own desires.[1] Comparing elements of WL to rococo art like Boucher’s can help us tease out both underlying arguments of the series and their aesthetic underpinnings. Moreover, examining the show through a rococo lens can open up new perspectives on what critic Isabelle Graw has dubbed the resort-ization of the contemporary art world—where we (unsurprisingly) also encounter numerous references to Boucher’s oeuvre today.[2]

Islands in the Stream

Like so many rococo tales, WL unfolds on an enchanted island. Its island resort acts as a modern-day Cythera, the mythical island of Venus. As Mary Sheriff observed, islands frequently emerged in French culture of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as vehicles to stage utopias of love and gallantry or, conversely, debauchery and debased morality.[3] The “enchanted” island was a locus in which spells of erotic promise could be indulged but also exited to either unsettle or affirm the dominant social order on the “mainland.” Such is the case in WL, where a cast of guests, staff, and locals inhabit the island and, like the cavorting couples that populate Watteau’s famous depiction of Cythera, proceed to twirl around each other in various dances of courtship and betrayal under the aegis of the goddess of love (Fig. 1). At the end of each WL season, a murder takes place, but, in rococo fashion, the show’s focus lies on displaying comparative forms of romantic entanglements and not impending death.

While all the characters in WL stage different approaches to romantic relationships, a central contrast is offered by two couples vacationing together: the finance bro Cam (Theo James) and his wife Daphne (Meghann Fahy) have invited his dour college roommate Ethan (Will Sharpe) and Ethan’s disaffected partner Harper (Aubrey Plaza) to Sicily, presumably because Ethan has recently made a lot of money that Cam wants to invest (at the resort, money is invested not earned). Cam and Daphne perform the joys of wealth and marriage free from mundane concerns like “politics” (they do not vote), while earnest Ethan and Harper claim to be truly in love even though they are no longer intimate. Cam tells Ethan that “everybody cheats,” while Ethan whines to Harper that he “never lies” to her. Daphne lets Harper in on the mind games she plays on Cam in order to make him jealous (this scene is ominously staged against a wallpaper featuring gaping trompe l’oeil grottos). Harper and Ethan style their relationship as “real” and “honest” as opposed to that of Daphne and Cam, who acknowledge the importance of illusion and games in maintaining the fiction of their romance and, ultimately, the happiness of their marriage.

We might think of these two couples as mirrors of each other, each person using the other as a site of self-projection. As Marion Hobson has argued, mirrors, as mobilized in rococo interiors, entertained the desire for a knowing indulgence of illusion.[4] The mirror’s reflection allowed for a type of social spectatorship that both integrated the individual into a social tableau and allowed for a knowing detachment: a space of reflection. Like the enchanted island, mirrors presented an opportunity to indulge in the pleasure of illusion as a movement outward from the self as well as a return to an interiorized self.

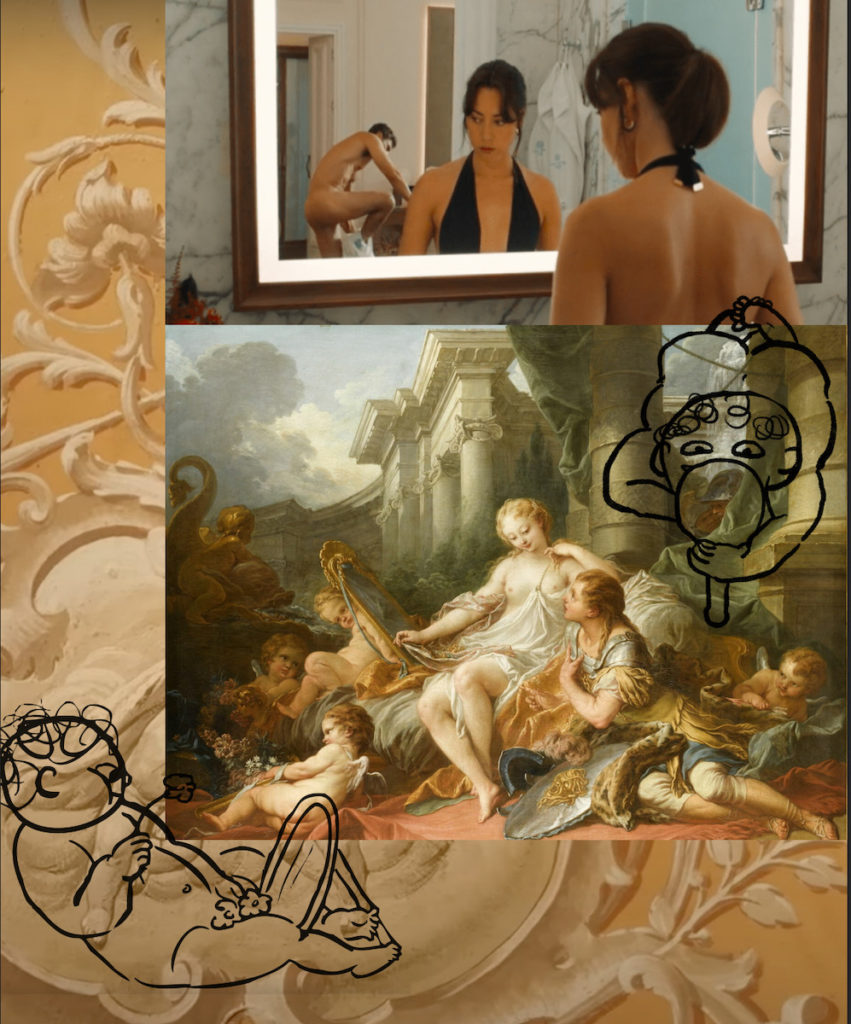

One might think of Boucher’s Renaud and Armide (1734) as a rococo meditation on the role of the mirror in amorous relations (Fig. 2). The enchantress Armide has seduced Renaud (a crusader in the Holy Land) and brought him to her enchanted island garden. Boucher depicts the lovers nestled together while two soldiers, who have come to rescue Renaud from the erotic lure of the sorceress, peer at them through a colonnade. In the source of the story, Torquato Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered (1581), they offer Renaud a mirror, which doubles as a shield, so that he might perceive the ways in which love and sex have made him effeminate and “soft,” spurring him to return to the battlefield. Yet Boucher’s image deploys the mirror in a much more ambiguous fashion.

In the painter’s mise-en-scène, playful putti, rather than the soldiers, hold up the mirror obliquely to the couple. It is unclear whether Renaud can see the mirror’s reflection, for he gazes upwards at Armide’s exposed breasts and alluring glance. What the viewer discerns in the mirror, however, is the hand that Renaud holds over his heart, a reflection that, as Sheriff suggests, presents a signification of love as an illusion. The painter invites the viewer to engage with this illusion in a double manner: beholders can allow themselves to enjoy Armide’s seductions while simultaneously acknowledging the spell of erotic love as an artful image, or fiction. Boucher’s mirror thereby both connects the lovers and, through the exposure of love’s fictions, also implies their separation. Their connection is not “real” but depends on illusion. Likewise, the beholder—like the soldiers—becomes a voyeur who can enjoy the pleasures and tensions of romantic connection as an imbroglio of mediating devices. Neither love nor the image is pure: love is artful illusion, and the illusion is a lovely one in which we find ourselves implicated.

White deploys mirrors in a similar manner. In a scene early on in WL, Harper and Cam go to her suite to get sunscreen and a swimsuit. The viewer sees the ensuing scene through a mirror, looking at Harper’s back while she looks into a mirror, which pictures her and Cam together, as Cam undresses and puts on Ethan’s shorts (see Fig. 2). Obvious pun intended: Cam’s member (a large prosthetic) flops out as he dons Ethan’s unused “suit” and fills it with his own “trunk,” piquing a reluctant Harper’s (and the titillated viewer’s) attention. Here, Boucher’s scenario is reversed, as if in a mirror. The reflection brings Cam’s manhood to the fore (the contrary of Renaud), as well as Harper’s desire not for Cam, but for what is lacking in her own relationship, namely a physical and erotic connection to her partner. Rather than clarity, the mirror points to disjunction.

Harper’s purported insight into the depth of her relationship with Ethan reveals itself as shallow, so long as she and Ethan deny the ways in which illusion and artistry might enhance their connection rather than detract from the delusion they share of its profundity. At the same time, White uses the mirror to invite the viewer to compare and evaluate the couples’ relationships. In this sense, one might ask, who is actually reflected in the mirror? As in Boucher’s painting, the reflection projected back at the viewer is one that juxtaposes two contrasting models of romantic relations: one based on the indulgence of illusion, the other rooted in a dogged adherence to an “honesty” that itself is illusory. The mirror becomes a site of voyeurism and reflection on the role of illusion and appearances in intersubjective relationships.

Class relations play a key role in these dynamics. Cam and Daphne’s play with surface illusions seems to be bound up with their wealth: they are frequently depicted shopping and use money and appearances to increase their desirability. Harper, on the other hand, is deeply skeptical about the ways in which Ethan’s recent wealth has brought them into the orbit of moneyed superficiality. She and Ethan both cling to the notion that there is an authentic self—and selfless, non-transactional love—equated with the purported “real” world outside of the bubble of life-as-a-luxury-resort. Who, then, is holding on to illusions in the WL constellation? The mirror that White holds up for the viewer renders both couples in a decidedly unpleasant light. They are neither appealing nor happy figures of identification. Yet White’s is not a plaintive critique of love degraded by the toxicity of money. Rather, he appears to be critiquing the idea of unadulterated “love” as a capitalist illusion.

Figures of Accommodation

The figures in White’s story who seem to grasp the implications of this critique are, not coincidentally, locals rather than guests. They are characterized first by their class (they work instead of accruing money through investments and assets) and second by their apparent embrace of “tact,” an acceptance that relationships are, if not transactional, then relational. They are attuned to the ways in which they must accommodate themselves to other people’s desires in order to turn relationships to their advantage and advance the interests of both parties. There is a significant difference here, however, between accommodation and exploitation. “Anyone who knows how to be accommodating can confidently hope to be pleasing,” wrote the Chevalier de Méré.[5] The characters who are most accommodating in White’s show are also those who are both most pleasing and, ultimately, happy. They are also the figures who realize that being accommodating in relationships does not really mean putting on a deceitful front. As White portrays them, these characters accommodate the desires of others in order to let those desires develop in a manner pleasing to both parties. In doing so, they maintain autonomy over their own interiority and ambitions while obliging external projections. We could best characterize these characters, therefore, as allegories of accommodation who inhabit an accommodation: the hotel that anticipates and caters to the wishes of wealthy guests.

One such character is Mia (Beatrice Grannò), a young singer-pianist who reluctantly joins her friend Lucia (an escort) in infiltrating the hotel in order to make money. Though initially hostile to exchanging sex for favors, Mia eventually accommodates herself to the idea that she can achieve her goal of snagging a gig as the resort piano player by seducing the gruff hotel manager Valentina (Sabrina Impacciatore). Mia transforms herself into an object of Valentina’s desire and gets her wish—accommodating herself to Valentina allows her to realize herself. This is not simply because the show cynically posits relationships as necessarily being transactional as opposed to deep. Instead, in embracing the illusion of intimacy, both she and Valentina are able to expand upon aspects of their selves (Valentina is gay, but has never been with a woman before Mia), which otherwise would remain untapped and dormant. The “seeming” does not, therefore, appear as opposed to the “being,” but rather White deploys the trope of the hotel accommodation as a means of staging how accommodation in social relations can open up metaphorical (and literal) doors. Fantasies here not only define identities but also create them, albeit only in relation to the fantasies of others. The self here is “promiscuous,” in a positive sense, as a turning of the self into “a quasi-decorative object of the world’s gaze,” i.e., one to be valued rather than paid (for labor done).[6]

For Lajer-Burcharth, Boucher was able to paint this new eighteenth-century split self, divided between an elusive interior and a promiscuous exterior. This comfortable self resides in a world of commodités like the guests at the White Lotus, where the staff ensures that everyone’s needs are being met all the time. Boucher’s The Lady on a Day Bed (1743) is arguably a key image of this new commodified self (Fig. 3). The painting’s protagonist appears in elegant nonchalance spread out on her day bed, facing the viewer, yet it is as if she were presenting us with a mask; her fingers seem to push against her visage, as Lajer-Burcharth notes, projecting it forward while betraying no hint of what lies behind. The painter only gives us a sense that the woman has an interior life that we cannot access, like the depths of the half-closed drawer of her nightstand. She exists to be seen by the pleased viewer, a receptacle that accommodates our speculative gaze.

This type of character finds an exhilarating echo in one specific—minor—role in WL: Isabella, a hotel employee with a ruthlessly persistent smile (Eleonora Romandini). Isabella is always grinning. No matter what happens, she greets everything (including the viewer) with a charming and toothy acceptance. Like Boucher’s woman on the day bed, we have no access to her interior life, though we assume she has one. And, like the reclining figure, she is both accommodating (smiling) and accommodated; her wishes appear to be granted consistently. In this sense, Isabella, who says little, offers the viewer not only a lesson about putting on a face that invites the projection of illusion, but also a prism for understanding the entire show. She is the allegory of accommodation, a role she wears comfortably, in the sense that she makes the fraught social dynamics of the hotel appear supple and fluid, turning them to a shared advantage. Indeed, that is why she has been hired: to mask the social relationships of a commodified world with a smile. And is that so bad? She might be the happiest character of all, though we will never know what lies behind her “front,” a façade that White presents more frequently to the viewer than the hotel guests.

Last Resort

The exclusive resort is a convenient site through which WL can explore the transactional elements of social and romantic relations precisely because elite resorts aim to relax their guests by minimizing class differences and attendant social frictions. If labor is to be introduced, it must remain disguised, infiltrating the resort through the production of illusions that uphold a sense of mutual advantage. It would seem that in order to tap into these dynamics and their implications for romantic love today, the rococo provides a compelling (and compliant) model for exploring how “tactful” illusion can function as a social aesthetic. Its insistent pliability and fixation on self-consciously deploying illusion in order to please allow the rococo redux not so much to critique as to probe the nature of transactional relations and their attending aesthetic models today.

The rococo and exclusive resorts also appear frequently in the world of contemporary art. As Graw has recently pointed out, exclusive vacation resorts have emerged as a new paradigm for contemporary art galleries.[7] Mega-galleries have begun to open resort hotels that double as spaces to exhibit and sell art where collectors can enjoy a shared pastime and taste for acquiring art as a value-accruing asset separated from the social conditions of its production as well as debate over its meaning.[8] Along with labor, there is no room for critique at a resort-gallery. “It’s a good feeling when you realize someone has money…cause then you don’t need to worry about them wanting yours,” Jennifer Coolidge’s character Tanya hisses at her assistant. In this context, in which the potential of art to fulfill a critical role is undermined (under the ostensible cause of advancing the interests of artists who profit from sales), what options are left to art and artists? Perhaps Boucher’s tactful self-marketing, with its staging of the art market as part and parcel of its meaning and production, offers a viable model of a utopian bubble where aesthetics mask realities of socio-economic relations.

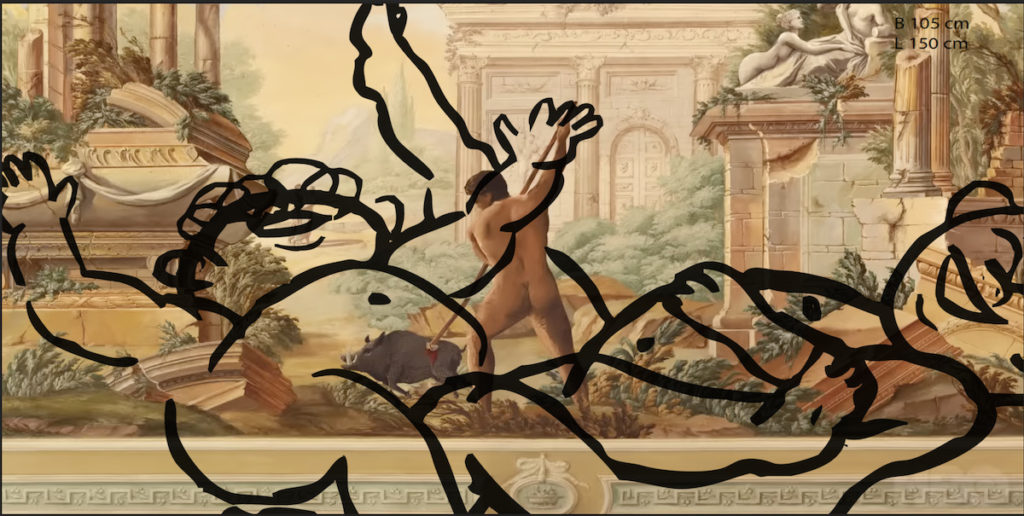

At the Frieze Art Fair in Los Angeles this year, Paris-based artist Matthew Lutz-Kinoy showed porcelain figures derived from the chinoiserie figure in Lady on a Day Bed (Fig. 4). These figurines have multiplied themselves, no longer in a cabinet, but as variations on ancient Egyptian table-like head-rests. These ironically hard pillows have accommodated an art market eager for new wares (they are “unique” multiples, each from a mold but painted differently), but are they really so commodious? Or might they be impishly tricky, like the putti holding up the mirror to Renaud’s heart? In a recent exhibition in Fredrikstad, Norway, meanwhile, the anonymous art collective Bossman also adapted Boucher drawings of love’s mischievous child-agents, playing on what Beverly Schreiber Jacoby called the “wall power” (or simplified graphic effects) of Boucher’s stand-alone drawings by turning them into literal printed outlines that cling to the wall, exposing themselves to the viewer like a bevy of wall “power bottoms” (Fig. 5).[9] Indeed, these putti know how to adapt: one can have them made to order, that is, to accommodate any size, surface, or circumstance. They are the ultimate fungible art commodity, existing only as reproductions that stretch themselves to the desires of whoever might purchase them. Why is the rococo back? It might be the best last resort.

Sasha Rossman teaches art history at the University of Bielefeld, Germany

Acknowledgments: The author gives special thanks to Corey Datz-Greenberg.

[1] Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, The Painter’s Touch: Boucher, Chardin, Fragonard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 8-85.

[2] Isabelle Graw, “Welcome to the Resort: Six Theses on the Latest Structural Transformation of the Artistic Field and Its Consequences for Value Formation” in Texte zur Kunst 127 (September 2022), https://www.textezurkunst.de/en/127/isabelle-graw-welcome-to-the-resort/.

[3] As well as, of course, colonial fantasies. Mary Sheriff, Enchanted Islands: Picturing the Allure of Conquest in Eighteenth-Century France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 32.

[4] Marian Hobson, The Object of Art: The Theory of Illusion in Eighteenth-Century France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

[5] Cited in Lajer-Burcharth, The Painter’s Touch, 14.

[6] Lajer-Burcharth, The Painter’s Touch, 57.

[7] Graw, “Welcome to the Resort.”

[8] Graw, “Welcome to the Resort.”

[9] See Beverly Schreiber Jacoby, François Boucher’s Early Development as a Draughtsman (New York: Garland Press, 1986), 271.

Cite this note as: Sasha Rossman, “Rococo Redux: On the Bloom of the White Lotus and the Return of the Rocaille” Journal18 (June 2023), https://www.journal18.org/6882.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.