Anne Hultzsch

Introduction

When Sophie von La Roche (1730-1807), often referred to as the first female professional journalist writing in German, described Paris to her readers in 1787, she began with accounting for the role women had played in the history of this “Zauberort,” this “magical place”: “The love and the violence, which our gender received in Paris, seem, according to history, to have been founded at the same time as the city.”[1] In particular, she reminded her readers of a “glorious … female government”: “for under the orders of Gallic women Rome was conquered, but under the supremacy of the priests Gaul was subjugated by the Romans.”[2]

Picking up on a narrative, surviving until today, of a matriarchal Gaul, La Roche purposefully foregrounded the role of women—favorably stressing their “merits and supremacy” compared to male priests, whose qualities “consisted only in the fact that they enjoyed the same respect as the women.”[3] She took care to demonstrate the thoroughness of the method underlying her gendered historiography, assuring her readers that she had studied descriptions of the city’s past and present, consulted plans, and would review archival sources.[4] While thus claiming the authority of the expert, La Roche also situated herself, a woman in the 1780s, into her history:

I read this course of ancient and modern history at my window, because I saw at the same time several hundred fine Parisian women walking in the garden of the Palais Royal, and twice as many men following them.[5]

Sitting by the window in her rented apartment overlooking the enclosed park of the Palais Royal, recently opened to the public and furnished with shopping arcades and event spaces, La Roche observed women navigating this built piece of modern urbanity—and men pursuing them (Fig. 1).

In this paper, I examine Sophie von La Roche’s travel writings, building upon the work of other researchers who have predominantly employed literary approaches to her expansive oeuvre. My aim is to understand how La Roche, as a privileged woman who nonetheless faced the restrictions of the patriarchal society she lived in, saw, navigated, and mediated the environments she found herself in, and how she instructed other women to do so. I adopt a close reading method for this, paying particular attention to passages that place La Roche physically in the described sites as well as to the spatial and linguistic mechanisms situating her more descriptive or critical passages on architecture and landscapes.

I examine a range of sites—foremost the window and what is visible from it—described in La Roche’s books on France and Switzerland to demonstrate how she consistently transgressed spatial and literary limitations placed on her gender, employing views in-between as lenses while claiming the position of the seeing subject, the active agent. I rely on the concept of “situated knowledges” developed by Donna Haraway, and suggest that La Roche practiced it herself. Haraway made “an argument for situated and embodied knowledges and an argument against various forms of unlocatable, and so irresponsible, knowledge claims.”[6] La Roche likewise embedded her own situation, both as physical location and as social identity, into her writing to present the places and sites she described to her readers in a particular, rather than universal, mode. As Jane Rendell has explained,

The … verb to situate describes the action of positioning something in a particular place, while the adjective situated defines something’s site or situation. Situatedness, then, is a way of engaging with the qualities of these processes of situating or being situated.[7]

I am able to situate La Roche both in the specific sites she wrote from—the window for one—and as a female author, a mother, a scholar, a networker, or a professional precisely because she did so herself through her writing.

This article is part of a wider investigation into the architectural agency women asserted through the practice of writing in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Architectural agency is here meant as the influence, or the power, these female authors had over architectural sense-making by rendering into words for the public to read their experiences within and opinions on the city and the building. In this period, women had a much stronger public voice than is often assumed within the historiography of architecture and the city. Indeed, they did write and publish, including on architecture, and in a wide range of genres. As Alison E. Martin has demonstrated in her work on La Roche, towards the end of the 1700s, women frequently “acted centrally as discursive mediators,” thus wielding influence on other women as well as on men. Martin dismantles the “systematic use of ‘separate spheres’ as an organizing concept,” arguing that “women were not immured in a private sphere but also occupied a surprisingly active role in the public sphere.”[8]

Though active and privileged by class, as a female author La Roche was of a lower status than her male peers in at least two ways. First, although she was a best-selling author, as a woman she would always first be seen either through accepted feminine exploits like her needlework, as Ruth P. Dawson has remarked, or through her physical appearance, as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe made clear when he referred to her as “slender and delicately built, rather tall than short,” without mentioning her professional work.[9] To be taken seriously, to be listened to, was difficult, even with her social status, then and now; we cannot forget this. Second, she had to circumnavigate restrictions placed on women to be able to publish at all, and she did this mainly by choosing more “popular” genres over those deemed “scholarly”—which might be the reason why her writing, as that of other women, has so far remained underexplored by architectural historians. The genres she chose—the novel, journalism, travel writing, moral tales, and instructions—were those more accessible to women precisely because they were more popular, aimed at the general reader, with the implication that they did not require as much expertise as those aimed at the (male) scholar. Clearly, it was those general readers who in turn navigated the city and its buildings, so it seems crucial to examine how a woman guided them around the city when writing histories of architectural experience.

From Court and Salon to Her Desk

Sophie von La Roche was born Sophie Gutermann in 1730 in Kaufbeuren, Bavaria, to a pietist middle-class family in which education was highly valued. She learned to read early and studied art and literature, languages (except for Latin, because she was a girl), music, and housekeeping. It was this education which served her well when, in 1753, she married Georg La Roche, private secretary to his adoptive (and assumed biological) father, Graf von Stadion. For almost three decades, La Roche lived at or close to one of the small and mid-size courts characterizing the German States at the time.

Partaking in court life and conversation, serving her husband’s as well as her own interests, she relied on being informed on a variety of topics. As part of these social constellations, La Roche became an increasingly respected figure, forming a circle of intellectuals around her and making use of the extensive libraries essential for intellectual court life. Five of her children, born during this time, survived into adulthood. It was at her father-in-law’s country seat in Bönnigheim that she wrote her first novel, Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771) translated as The History of Lady Sophia Sternheim in 1776.[10] Initially published anonymously, the author’s identity was soon revealed, and with it came fame and a position in intellectual circles.

Playing on La Roche’s own experience of life at a minor court, Sternheim’s plot revolves around the social frictions between the court’s aristocracy, landed gentry, and the rising middle classes, with the female protagonist trapped between virtue, sexual seduction, and upwards social mobility.[11] When La Roche moved with her family to Koblenz—where her husband was rapidly rising in the ranks of civil service, eventually gaining the ennobling “von” in his family name—she established a successful literary salon. Goethe, who visited in 1772, was gripped by the conversations making up the salon and called it a “Kongress,” implying a multitude of voices debating a shared subject.[12]

However, the life of salonnière came to an end when her husband lost his position, falling out of favor with both church and aristocracy, and the La Roches left courtly life and moved to Speyer. It was now, in her 50s, that Sophie von La Roche began to regard writing as a profession: something still rare for a woman, but achieved by La Roche and increasing numbers of other women, often without much hint of the radical. Now relying on earning money with her writing, La Roche began to explore both the periodical and the travel book genres.

Between 1783 and 1784, she published Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter (Pomona for Germany’s Daughters), one of the first German magazines for women by a woman. The German-speaking states lagged behind other European regions in this regard—England, for instance, had seen Eliza Haywood’s Female Spectator (1744-46)—and while there had been earlier German journals for women, apart from two minor short-lived publications, these had been written by men.[13] La Roche discovered the potential of a strong female readership and took to addressing them directly, taking care, however, not to alienate her male readers.[14] More articles and books followed, strategically planned to establish her authorial identity, protect her intellectual property, and ensure her income.[15] La Roche’s intention was made clear in Pomona’s opening essay: while previous ladies’ magazines—here she refers to two journals written by men—“show my female readers what German men consider useful and pleasing to us … Pomona will tell you what I think of it as a woman.”[16]

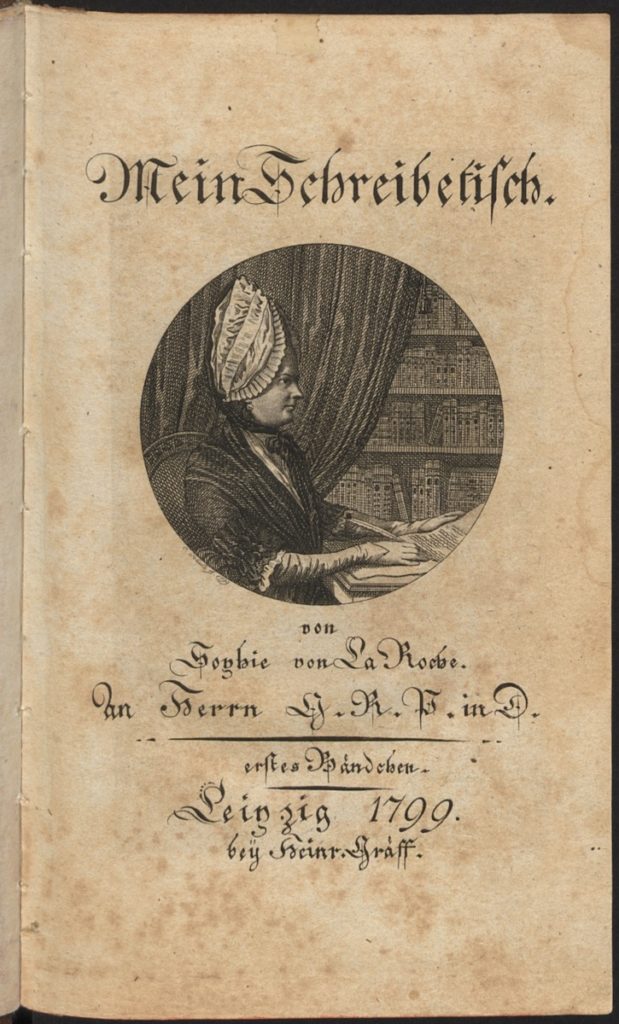

As a woman, La Roche clearly had still more to say. In the mid 1780s, as a working, upper middle-class woman now distant from but still building on the networks established at court, she turned to travel writing. She travelled purposefully to write about her experiences and published, in quick succession, a book each on France and Switzerland (both 1787) and one covering Holland and England (1788).[17] Before her death in 1807, more travel books were followed by her semi-autobiographic Mein Schreibetisch (My Writing Desk, 1799), which included bibliographies (Fig. 2). As Daley has pointed out, the “percentage of women writers in La Roche’s reading list exceeds the number of female-authored works a mid-twentieth-century scholar might be familiar with.”[18]

This foregrounding of women and their agency runs throughout La Roche’s oeuvre. She supported other women writers, for instance offering the novelist Caroline von Wolzogen her first publishing opportunity in Pomona.[19] And when, in her book on Holland and England, La Roche introduced London, she quoted Catharine Macaulay, author of the eight-volume History of England (1763), instead of a male historian.[20] Throughout her non-fiction writing, I argue, La Roche developed a citational strategy akin to those of feminists today. Perhaps she would have agreed with Sara Ahmed: “Citations can be feminist bricks: they are the materials through which, from which, we create our dwellings.”[21]

La Roche created her writerly dwelling purposefully and skillfully, and while she did not always transgress in her writing, she did so on a methodological level. This seems particularly pertinent as she aimed at, and reached, both female and male readers, as Elystan Griffiths has demonstrated.[22] As I will show, she negotiated the gendered spheres of both city and print to serve all her readers. She had several good reasons for doing so, including a feminist impulse to Enlightenment as well as subsistence: she was pragmatic and needed the money, which meant she could not afford to antagonize influential (male) readers. I suggest that, besides that of the novelist, journalist, and travel writer, La Roche also claimed the identity of the historian for herself. The genres she wrote in must be seen as containers for a range of practices, from history to literary and architectural criticism to sociology, to name just a few.

Strasbourg: The City and the Artist

When La Roche employed her window in Paris to situate her history of the city, she used a strategy readers would soon be familiar with from her writing. Frequently, the window is a marker for her arrival in a new place, which she used to assess her unfamiliar surroundings simultaneously in detail and in sweeping panoramas, zooming in and out, while situating her body and herself from her own vantage point. From the safety of her lodgings, she surveyed the city and its people. In Strasbourg, which she visited in 1784 at the beginning of her tour of Switzerland, she could see the cathedral from her room: “From my window I see the wonderful tower of the cathedral as my nearest neighbor, I have looked at it with binoculars and marvelled at the execution of this bold building.”[23] Emphasizing a haptic closeness to the cathedral tower, La Roche personified it as her “neighbor,” whose description is enhanced through her use of the optical device to see every minute detail. Zooming in on its materiality and structure, La Roche positioned herself as more than a picturesque viewer; rather, she demonstrated an analytical, knowledgeable eye for style and material which she engaged again when entering the building.

Having left her window, we find her a little later in the cathedral’s south portal, responding on an emotional level to a pair of sculptures which had been carved by Sabina von Steinbach (La Roche gives Erwin as her last name, this was her father’s first name):

but with an increased movement of the soul I stood before the two carved figures at the entrance to the side door of the church … Both were made by Sabina Erwin, the daughter of the master builder … The contemplation of the whole construction of the magnificent church increased my respect for her spirit and diligence, for this last quality must always be connected with the first if one wants to produce something great, beautiful or useful. Sabina, in the spirit of her father, had grasped the bold proportions of one of the most splendid Gothic buildings, and at the same time had shown the own tender taste of a fine feminine soul in the form and garb of these two carved figures.[24]

Sabina von Steinbach is an interesting case within feminist art history (Fig. 3). Oscillating between artist heroine and mythical invention, her figure is traceable through the last two (and, including La Roche, three) centuries of feminist art writing, from the Cosmopolitan’s Art Journal, published in New York by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1856-61), to Linda Nochlin’s influential essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (1971).[25] Featuring in these narratives as “a female sculptor of no mean eminence” (Art Journal) or a “legendary sculptor” (Nochlin), yet no Michelangelo (Buckler), Steinbach was the daughter of Erwin von Steinbach, a master mason on the cathedral building site in the thirteenth century. She is said to have worked on the stone carvings throughout the building, with some narratives telling us that she even rose to become the master mason herself upon her father’s death, a plotline often discarded due to the apparent impossibility of a woman being accepted in this position at the time.

Be that as it may, two allegorical female figures of Ecclesia and Synagoga, personifying Christianity and Judaism, in the south portal have been specifically ascribed to her. La Roche, among the writers I have just quoted (one of them a man), and notwithstanding factual accuracy, highlighted here again the work of a woman, practizing her citational strategy not only regarding written but also built works. La Roche’s very soul is moved by the work of a woman to whom she ascribed precisely that skill which she surely craved for herself: Sabina had “grasped” a male domain—Gothic boldness—and refined it with her “own tender taste of a fine feminine soul.” The feminine, in La Roche’s eyes, is in no way diminishing. Perhaps she saw herself as having mastered masculine spheres of literature while also enhancing them with her situated take on feminine sensibility.

A decade before La Roche praised Sabina von Steinbach’s work, Goethe had done so for her father, Erwin von Steinbach, in the essay “Von Deutscher Baukunst” (On German Architecture, 1773), published both in a literary context by Johann Gottfried Herder as well as for a more specialized audience in the first German architectural magazine, the Allgemeines Magazin für die bürgerliche Baukunst (General Magazine for Civic Architecture).[26] Interestingly, Goethe wrote his essay precisely during the period in which La Roche had received him in her literary salon in Koblenz, partaking in conversations and debates characterized by Empfindsamkeit, or sensibility. Making private, intense emotions public, sensibility was a literary Enlightenment phenomenon brought into fashion through epistolary fictions by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in France, Samuel Richardson in England, and Sophie von La Roche in Germany. La Roche was renowned for this mode of writing, exploring and describing her emotional responses, a “skill” said to be particularly suited to women. Opening many doors to female authors, it simultaneously turned into a central concept within architectural discourse, as buildings became expected to trigger a response within the observer.[27]

Goethe is even more passionate, in a Sturm und Drang style, about Erwin von Steinbach’s work—his essay is a eulogy to the architect master mason—than La Roche would be on Sabina von Steinbach’s sculptures. However, Goethe presented himself as a rather passive viewer, subjected to external influences. He had to “unlearn” the classical preferences of his upbringing, which made him an “enemy of the convoluted arbitrariness in Gothic ornaments.”[28] As Klaus Jan Philipp has demonstrated, Goethe’s process followed three stages of perception: first, he lamented being blinded by the wealth of ornamental detail; second, he observed the whole, merging the details; and only in the end was he able to acknowledge the creator’s (Steinbach’s) genius. Emphasis is on the dialogue with the individual building and the genius creator, as Philipp writes.[29]

La Roche had constructed a similar conversation with Sabina von Steinbach as an extraordinary individual, declaring that if the location of her grave had been known, she would have visited it with the same emotions with which she had observed her works.[30] There is no such reverence towards Erwin von Steinbach in La Roche’s texts. Instead he is only mentioned as a father, a reference that skillfully inverts the common practice of mentioning women only as daughters or wives, once again showcasing La Roche’s citational strategy. However, even if La Roche presents Sabina von Steinbach’s carving skills as extraordinary, she does not do so despite Steinbach being a woman. Steinbach, in La Roche’s account, is no exception to the rule, no rare specimen of a woman equal to a man in terms of talent. She is introduced neither as an eccentric nor less or more feminine than any woman “should” be. Her gender is important, as it adds another depth (“soul”) to the masculine genius of Gothic boldness, but it is in no way, explicitly or implicitly, diminishing; no excuses are made for praising a female artist.

Swiss Lakes: The City in the Landscape

Having travelled on into Switzerland, we find La Roche again at her window. Addressing her children after her arrival in Zurich, she lamented the view “was not as beautiful as it was fifteen years ago when your father looked out of this window, for the lake was covered with a mist and the mountains with clouds.”[31] Again employing the liminal space of the window both literally and metaphorically, she situates herself as wife and mother in addition to tapping into the then emerging literary image of the Alps as a site of awe. As Erdmut Jost has demonstrated, La Roche was familiar with Albrecht von Haller’s 1729 poem Alpen, one of the first texts to articulate the idea of mountains as sublime rather than eliciting fear and disgust.[32] In 1784, even when she could not see the awe-inspiring Alpine summits, the imaginary she shared with her readers enabled her to evoke them.

Moving on, Lucerne is again introduced by the gaze out of her window. There is disappointment at first, due to her room facing a narrow street. Soon—in fact, after exactly fifteen minutes, as she assured her readers—she discovered, happily, “I can see straight into the parlor of the wife of a citizen who has just come from church with her two girls.” Now “very pleased with my window,” she contentedly observed the woman teaching her daughters how and where to put their clothes away.[33] As La Roche herself had addressed her children, she empathized with this mother instructing her daughters. Having a subject to look at was crucial to her liminal position in the window, and, as a travelling writer and journalist, her aim was to analyze spaces and their occupants, preferably those with whom her readers could relate to and empathize. In this sense, a Bürgersfrau (citizen’s wife) was one of the most relatable subjects she could have chosen. Implicitly, she constructed a relationship from mother to mother, as she had towards Sabina von Steinbach, then from artist-writer to artist-sculptor, rendering her writing plausible and believable to her readers and positioning herself as the expert on the respective field of urban life.

Coming back to Haraway, I argue that La Roche’s use of the window as a site of both observation and writing helped her to construct situated knowledges. She exploited her own gendered, and thus in certain terms liminal and subaltern, perspective to construct a situated model of architectural experience.[34] In her description of the details, she rendered spaces as they were lived-in, creating a particular rather than universal level of meaning. As Haraway writes, “Situated knowledges are about communities, not about isolated individuals. The only way to find a larger vision is to be somewhere in particular.”[35]

La Roche’s windows function both as devices to observe, situate, and thus know, but also as sites and tropes of communication. This becomes apparent in Lausanne, where La Roche, as before, described her gaze through a window to “bid all my loved ones a hearty good morning,” exclaiming that she “would like to be able to give everyone the joy that I have been relishing at my window for half an hour.” Here again she invokes a reference to time, indicating the duration she spent contemplating the view to the outside. Having set the scene, with she herself in the window looking down a hill toward Lausanne, she proceeds to itemize the landscape: “two lovely flower gardens” in the foreground, “the whole of Lausanne” and “the wide view of the lake” in the middle ground, and in the background, “like an immense garden,” “the hills of the Principality of Chablais, and on my right, the Vaud, spread out, as far as the mountain range of the Jura.”[36]

Giving a more than 180-degree view across the lake—stretching the physically possible and perhaps surpassing the range of landscape painting—La Roche summons the landscapes of the Romandy, the western French-speaking parts of Switzerland, and sent them as a verbal postcard to her “loved ones.” She situates herself as a seeing, loving, and loved subject and employs this status to describe the city in the landscape. Not only is there her careful rendering of the view, but there is also a joy in sharing it. Perhaps most important is that La Roche owned both the joy and its sharing by placing it into her (“my”) window. As she adopts an architectural space as a literary device, it is her voice, her experience and sentiment, her moment and space, which she claims and fixes in print.

Aware of the power of such a sweeping glance across territories, she continued to exploit Swiss topography when staying in Nyon, also on the shores of Lac Léman north of Geneva. Stopping for lunch in a historic building, she engaged historical fiction to situate herself. Conjecturing a noble, long-dead female occupant gazing out of her window, La Roche imagined how

no doubt the lady sat with her visitors on the stone bench by the small narrow windows on beautiful summer days, looking at the sunlit buildings of the Savoy town and the Ripaille monastery, as I did.[37]

By evoking this past moment, La Roche used her own gaze from, and her own body in, the space of the “narrow window” to express an embodied historical consciousness, implying the possibility of a conversation with past spirits.

Alison Martin discusses a similar passage in La Roche’s book on England, pointing to the relationship La Roche builds with her readers. Writing about La Roche imagining having stood in the same spot where Pope had once written a poem, Martin remarks, “Sentimentality thus functioned as a means by which to move the reader through its reference to the loss of past greatness.”[38] By evoking a past gaze, famous or anonymous, La Roche constructed history as something based on experience, on the senses, on the practice of sensibility, rather than merely on data enshrined in chronicles. Reading silently, a practice increasingly common during La Roche’s time, would have strengthened the bond between reader and author. Instead of listening to a real voice impersonating the author, silent readers had to imagine hearing the author’s voice in their head.[39] La Roche instructed her readers in this skilled reading throughout her oeuvre, and exercising the readerly imagination played a big part in this educational project. She prompted her readers, of any gender, to visualize the city and its landscapes in their minds and to search for an emotional response while occupying liminal positions, such as the window. While not exclusively feminine, the window here operates as a trope for the female position that La Roche carved for herself between the domestic and the public spheres.

The City “en miniature”

As a scholar armed with well-informed research and references, La Roche fashioned gendered histories of the city, foregrounding both contemporaneous conditions of women as well as their historical roles in the formation of what she regarded as the European city. She developed citational strategies that resonate with twenty-first-century feminism, making visible female authors and artists. She presented her knowledges as situated, produced from the sites of her own experiences. As a writer-viewer, employing the liminal space of the window both literally and figuratively, she focused on specific situations featuring individuals in contained spaces: microcosms encapsulating in miniature the characteristics of something much larger: urban life.

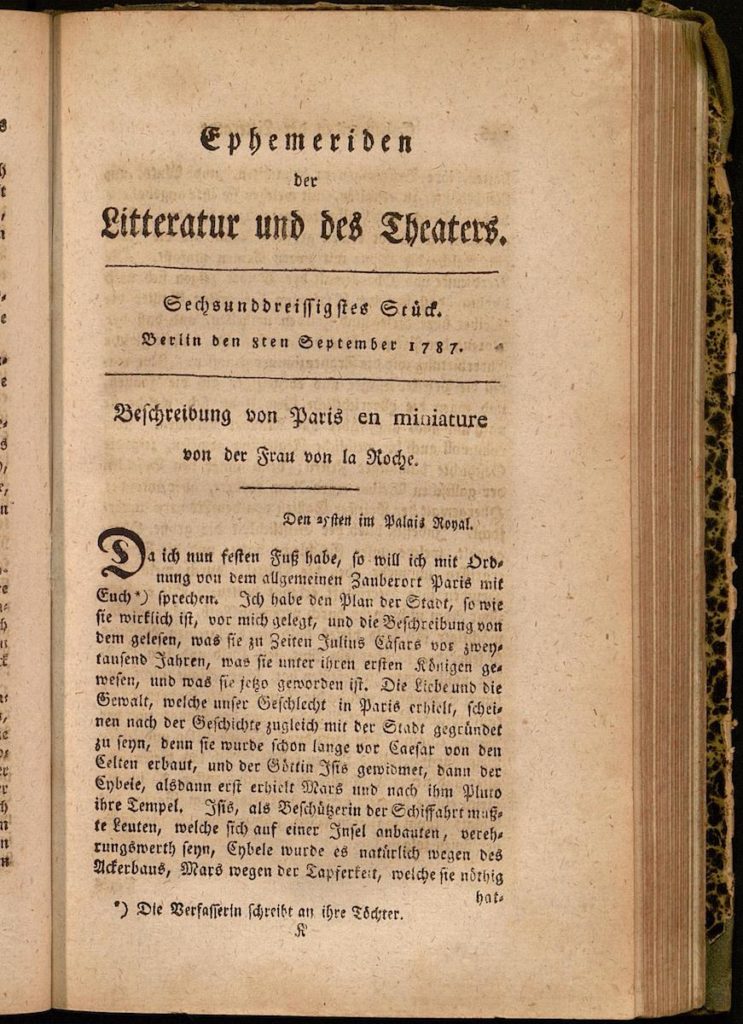

In her account of France, in parts republished aptly entitled “Paris en miniature,” she described the advantages of having taken an apartment in the Palais Royal (Fig. 4):

Strangers who take lodgings here can become acquainted in a month with the spirit, the manners and the labor of Parisians in the Palais Royal, and for this they are really obliged to the Duc [of Orléans], as otherwise they would have to walk through many parts of the immense city in order to collect something whole; but here everything happens quickly.[40]

All of Paris, the whole metropolis, she saw compressed into this partly brand-new architectural complex. Inaugurated only shortly before La Roche stayed there in 1785, the six-storey apartment buildings had been commissioned by the then Duc de Chartres, later Orléans, to bolster his income. Narrow bays separated by a colossal composite order were repeated over 200 times around the park, which was extremely popular for both Parisians as well as visitors with its mixture of entertainment, shopping, and promenading.[41] Writing about it in terms of time, money, and gender, Sophie von La Roche certainly had her finger on the pulse of her time.

In this article, I have focused on specific situations in a set of small to mid-range cities, from Lausanne to Strasbourg, framed by her account of the Palais Royal literally as “Paris en miniature.” Brigitte Scherbacher-Posé has suggested that Sophie von La Roche wrote “not from the scholars’ study but rather ‘on the spot’ and with the Zeitgeist in mind.”[42] Indeed, in her travel writing, she often placed herself within the sites she described, occupying liminal spaces like windows which had to be appropriated by a woman who operated in public and private simultaneously, dissolving each of these spheres by living in the field of tension shaped by identifying as a scholar, mother, salon hostess, and journalist. Her autobiography, then, is situated very precisely on her desk—Mein Schreibetisch—rather than in the salon, at court, or even at home. Entirely embedded in contemporary literary trends, and an expert at employing her status as a married, later widowed, woman and mother for professional pursuits, La Roche is neither Immanuel Kant’s disinterested aesthetic subject nor Edmund Burke’s weak, passive, and delicate female object. She fits in with neither of these concepts that dominate the historiography of late eighteenth-century aesthetics in art and architecture. La Roche is both too close to her objects of contemplation, and too independent and implicitly transgressive. Moreover, she invites her readers to stay equally close to her and join her in playing the rules of gender to their advantage.

As I have listened to Sophie von La Roche guiding her readers around some of the cities she visited herself, it has become apparent that she employed Empfindsamkeit, or sensibility, to show female strength, authority, and agency. Through her situated descriptions, we glean lived experiences in the city, we observe gendered and supposedly separate spheres mingling, clashing, and at times dissolving (or being ignored). In La Roche’s writing there are no static separate spheres lived by women. Separations exist—she was privileged by class, and no radical feminist—but these are at times porous, whereas at other times they bounce and vibrate. As her position in the window shows, she relied more on an entangled model of discourses in which binary identities, and spheres, became shifting props and tools rather than oppressing patriarchal molds. Through her writing, she models such liminal experiences for her readers. The window places her in between private and public, interior and exterior, and simultaneously enables her to see and be seen as well as listened to. Today, it is up to us to listen.

Anne Hultzsch is an architectural historian at ETH Zurich where she leads the ERC-funded project Women Writing Architecture 1700-1900

Acknowledgements: This article is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 949525).

[1] “Die Liebe und die Gewalt, welche unser Geschlecht in Paris erhielt, scheinen nach der Geschichte zugleich mit der Stadt gegründet zu seyn.” Sophie von La Roche, Journal einer Reise durch Frankreich (Altenburg: Richter, 1787), 42. All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted.

[2] La Roche, Journal einer Reise durch Frankreich, 43. “Wie ruhmvoll auch die weibliche Regierung gewesen, zeigt die Geschichte damaliger Zeiten; denn unter den Befehlen der gallischen Weiber ward Rom erobert, aber unter der Obergewalt der Priester Gallien von den Römern unterjocht.”

[3] La Roche, Journal einer Reise durch Frankreich, 43. “Die Verdienste und Obergewalt der Weiber zeigen sich noch darin, daß bey der Regierung der ersten Gallier die Weiber über Krieg und Frieden urtheilen, und daß der Vorzug der Priester blos darinne bestand, daß sie gleiche Ehrerbietung wie die Frauenzimmer genossen.” In recent scholarship, the narratives of a matriarchal Gaul are often belittled; see, for example, Helmut Birkhan, Nachantike Keltenrezeption: Projektionen keltischer Kultur (Praesens, 2009), 589–614.

[4] La Roche, Journal einer Reise durch Frankreich, 42, 44. One of the works she owned and almost certainly consulted was Louis-Sébastien Mercier, Tableau de Paris, 12 vols. (Amsterdam, 1782). See Brigitte Scherbacher-Posé, “Die Entstehung Einer Weiblichen Öffentlichkeit Im 18. Jahrhundert: Sophie von La Roche Als “Journalistin”,” Jahrbuch für Kommunikationsgeschichte 2 (2000): 35.

[5] “Ich las diesen Zug alter und neuer Geschichte an meinem Fenster, da ich zu gleich einige hundert artige Pariserinnen im Garten des Palais Royal spazieren gehen, und zweymal so viel Männer ihnen folgen sah.” La Roche, Journal einer Reise durch Frankreich, 43.

[6] Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 583, https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

[7] Jane Rendell, “Sites, Situations, and Other Kinds of Situatedness,” Log 48 (Winter/Spring 2020): 27.

[8] Alison E. Martin, Moving Scenes: The Aesthetics of German Travel Writing on England 1783-1830 (London: Legenda, 2008), 41. See also Amanda Vickery, The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).

[9] Ruth P. Dawson, The Contested Quill: Literature by Women in Germany, 1770-1800 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2002), 17. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit. Autobiographische Schriften 1, ed. Erich Trunz (Hamburg: Beck, 1981), 561.

[10] Sophie von La Roche, Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim. Von einer Freundin derselben aus Original-Papieren und andern zuverläßigen Quellen gezogen, ed. Christoph Martin Wieland, 2 vols. (Leipzig: Weidmanns Erben und Reich, 1771); La Roche, The History of Lady Sophia Sternheim, Attempted from the German of Mr Wieland, trans. Joseph Collyer (London: T. Jones, 1776).

[11] See Dawson, The Contested Quill, 103–110; and Barbara Becker-Cantarino, Meine Liebe Zu Büchern: Sophie von La Roche Als Professionelle Schriftstellerin (Heidelberg: Winter, 2008).

[12] Goethe, Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit. Autobiographische Schriften 1, 557. See Monika Nenon, “Sophie von La Roche’s Literarische Salongeselligkeit in Koblenz-Ehrenbreitstein 1771-1780,” The German Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2002): 282–296, https://doi.org/10.2307/3072710.

[13] Pomona’s recent precursors were Ernestine Hofmann’s Für Hamburgs Töchter and Charlotte Hezel’s Wochenblatt für ‘s Schöne Geschlecht (both 1779). See Ulrike Weckel, Zwischen Häuslichkeit und Öffentlichkeit: Die ersten deutschen Frauenzeitschriften im späten 18. Jahrhundert und ihr Publikum (Tübingen: M. Niemeyer, 1998). See also Jennie Batchelor and Manushag N. Powell, eds., Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690-1820s: The Long Eighteenth Century (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018); and Juliette Merritt, Beyond Spectacle: Eliza Haywood’s Female Spectators (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004).

[14] Elystan Griffiths, “Sophie von La Roche’s Zeitschrift Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter und der literarische Markt der 1780er Jahre im Lichte unveröffentlichter Briefe,” German Life and Letters 73, no. 2 (2020): 163, https://doi.org/10.1111/glal.12259.

[15] See Griffiths, “Sophie von La Roche’s Zeitschrift Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter;” and Scherbacher-Posé, “Die Entstehung einer weiblichen Öffentlichkeit im 18. Jahrhundert.”

[16] Sophie von La Roche, “An meine Leserinnen,” Pomona für Teuschtlands Töchter, no. 1 (January 1783): 3.

[17] La Roche only set out on any of her travels that would become a subject of her books after she had acquired a publishing contract. See Helga Meise, Sophie von La Roche et le savoir de son temps (Reims: Université de Reims Champagne-Ardennes, 2013), 21. More widely on her travel writing, see Linda Kraus Worley, “Sophie von La Roche’s Reisejournale: Reflections of a Traveling Subject,” in The Enlightenment and Its Legacy: Studies in German Literature in Honor of Helga Slessarev, ed. Sara Friedrichsmeyer and Barbara Beker-Cantarino (Bonn: Bouvier, 1991), 91–103.

[18] Margaretmary Daley, “Maxims of Leadership for a Silent Readership: Sophie von La Roche’s Pomona Für Teutschlands Töchter and Mein Schreibetisch,” in Realities and Fantasies of German Female Leadership: From Maria Antonia of Saxony to Angela Merkel, ed. Elisabeth Krimmer and Patricia Anne Simpson (Boydell & Brewer, 2019), 13, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787445628.003.

[19] “Schreiben einer jungen Dame, auf ihrer Reise durch die Schweiz,” in Pomona (1784), 3:472–487. See Daley, “Maxims of Leadership for a Silent Readership,” 5.

[20] Sophie von La Roche, Tagebuch einer Reise durch Holland und England (Offenbach am Main: Ulrich Weiss und Carl Ludwig Brede, 1788), 209. See Catherine Macaulay, The History of England, 8 vols. (London: J. Nourse, R. and J. Dodsley, W. Johnston, 1763-83).

[21] Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 16. It is important to add that La Roche never went as far as Ahmed, who does not cite white men in Living a Feminist Life.

[22] Griffiths, “Sophie von La Roche’s Zeitschrift Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter,” 163. See also Martin, Moving Scenes, 63.

[23] “Ich sehe aus meinem Fenster den wundervollen Münsterthurm als nächsten Nachbar, habe ihn mit dem Fernglas betrachted, und die Ausführung dieses kühnen Gebäudes angestaunt.” Sophie von La Roche, Tagebuch einer Reise durch die Schweitz (Altenburg: Richter, 1787), 17. Note on the translation: it is unclear whether La Roche here uses a binocular telescope or whether it is actually a monocular device. The German term Fernglas can refer to both, and both types were in circulation at the time, with binocular theatre glasses increasingly produced from the early 1700s, when achromatic lenses became available.

[24] “mit einer vermehrten Bewegung der Seele stand ich aber vor den zwei Bildsäulen an dem Eingang der Seitenthüre der Kirche … Beyde sind von Sabina Erwin, der Tochter des Baumeisters, verfertigt … Die Betrachtung des ganzen Baues der herrlichen Kirche vermehrte meine Hochachtung für ihren Geist und Fleiß, denn diese lezte Eigenschaft muß allezeit mit dem ersten verbunden sein, wenn man etwas Großes, Schönes oder Nützliches hervorbringen will. Sabina hatte nach dem Geist ihres Vaters die kühnen Verhältnisse eines der herrlichsten gothischen Gebäude gefaßt, und zugleich den eignen zärtlichen Geschmack einer feinen weiblichen Seele in der Gestalt und dem Gewand zweyer Bildsäulen gezeigt.” La Roche, Tagebuch einer Reise durch die Schweitz, 17–18. For Sabina’s story see also Leslie Ross, Artists of the Middle Ages (Westport, Conneticut: Greenwood Press, 2003), 152–153.

[25] “Women-Artists,” Cosmopolitan Art Journal 3, no. 1 (1858): 47; Ernst Karl Guhl, Die Frauen in der Kunstgeschichte (Berlin: Guttentag, 1858), 46–48; G. G. Buckler, “The Lesser Man,” The North American Review 165, no. 490 (1897): 304; Linda Nochlin, “Why Are There No Great Women Artists? (1971),” reprinted in Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 169.

[26] Johann Wolfgang Goethe, “Von Deutscher Baukunst,” in Von Deutscher Art und Kunst: Einige fliegende Blätter, ed. Johann Gottfried Herder (Hamburg: Ben Bode, 1773), 121–136; Goethe, “Von Deutscher Baukunst,” Allgemeines Magazin für die bürgerliche Baukunst 1, no. 1 (1789): 84–93.

[27] See, for instance, Sigrid de Jong, Rediscovering Architecture: Paestum in Eighteenth-Century Architectural Experience and Theory (London & New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014); or G. L. Hersey, “Associationism and Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Architecture,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 4, no. 1 (1970): 71–89, https://doi.org/10.2307/2737614.

[28] Goethe, “Von Deutscher Baukunst,” 85. “Feind der verworrenen Willkührlichkeiten gothischer Verzierungen.”

[29] Klaus Jan Philipp, Um 1800: Architekturtheorie und Architekturkritik in Deutschland zwischen 1790 und 1810 (Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges, 1997), 72.

[30] La Roche, Tagebuch einer Reise durch die Schweitz, 18.

[31] La Roche, Tagebuch einer Reise durch die Schweitz, 70. “Es war aber nicht so schön als vor fünfzehn Jahren, da Euer Vater aus diesem Fenster sah, denn der See war mit einem Nebel und die Gebürge mit Wolken bedeckt.”

[32] Erdmut Jost, Landschaftsblick und Landschaftsbild: Wahrnehmung und Ästhetik im Reisebericht 1780-1820. Sophie von La Roche, Friederike Brun, Johanna Schopenhauer (Freiburg i. Br: Rombach, 2005), 146–154.

[33] La Roche, Tagebuch einer Reise durch die Schweitz, 121–22. “Die Aussicht von meiner Stube misfiel mir anfangs, weil sie in eine enge Straße gegen das Gebäude der Wendeltreppe von dem Pallast des päpstlichen Gesandten geht, aber seit einer Viertelstunde bin ich sehr mit meynem Fenster zufrieden, weil ich gerade in die Stube einer Bürgersfrau sehen kan, welche so eben mit ihren zwey Mädgens aus der Kirche kam.”

[34] She was not the only one doing this. Besides other women, there were also male writers who purposefully exploited their subaltern outsider positions to frame a more accessible and more concrete view on the built environment. See, for example, Richard Wittman on Germain de Brice in Architecture, Print Culture and the Public Sphere (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), 19–24.

[35] Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 590.

[36] La Roche, Tagebuch einer Reise durch die Schweitz, 299. “Ich gebe allen meinen Lieben einen herzlichen guten Morgen, und möchte Allen die Freude geben können, welche ich seit einer halben Stunde an meinem Fenster genoß. Ueber zwey artige den Berg abliegende Blumengärten hin sehe ich ganz Lausanne zu den Füssen dieses Hauses, und über diese die weite Aussicht auf den See, an dessen Ufer zur Linken die Gebürge des Fürstenthums Chablais, und zu meiner Rechten das wie ein unermeßlicher Garten ausgebreitete Waadtland, bis an die Bergkette des Jura.”

[37] La Roche, Tagebuch einer Reise durch die Schweitz, 223. “Das Haus gehörte ehemals einer adelichen Familie, und gewiß saß die Dame mit ihren Besuchen in schönen Sommertagen auf der steinern Bank an den kleinen schmalen Fenstern, und betrachtete die von der Sonne beleuchteten Gebäude der savoyschen Stadt und des Klosters Ripaille, wie ich.”

[38] Martin, Moving Scenes, 52.

[39] See chapter 3 in Anne Hultzsch, Architecture, Travellers and Writers: Constructing Histories of Perception 1640-1950 (Oxford: Legenda, 2014); Also see Elspeth Jajdelska, Silent Reading and the Birth of the Narrator, Studies in Book and Print Culture (Toronto, London: University of Toronto Press, 2007). La Roche spoke in favor of silent reading herself. See Pomona, 2:845–49.

[40] “Fremde, welche hier eine Wohnung nehmen, können in einem Monat den Geist, die Sitten und die Arbeit der Pariser im Palais Royal kennen lernen, und sind dafür wirklich dem Herzog [von Orléans] verpflichtet, indem sie sonst viele Theile der ungeheuern Stadt durchlaufen müßten, um etwas Ganzes zu sammeln; aber hier geht alles hurtig.” Sophie von La Roche, “Beschreibung von Paris En Miniature,” Ephemeriden der Litteratur und des Theaters 6 (September 3, 1787): 150.

[41] See Andrew Ayers, The Architecture of Paris: An Architectural Guide (Stuttgart and London: Edition Axel Menges, 2004), 47–49.

[42] Scherbacher-Posé, “Die Entstehung einer weiblichen Öffentlichkeit im 18. Jahrhundert,” 25. “Neu ist beispielsweise, dass Sophie von La Roche nicht aus der Gelehrtenstube, sondern “vor Ort” und den Zeitgeist im Auge schreibt.”

Cite this article as: Anne Hultzsch, “The City “en miniature:” Situating Sophie von La Roche in the Window,” Journal18, Issue 15 Cities (Spring 2023), https://www.journal18.org/6782.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.