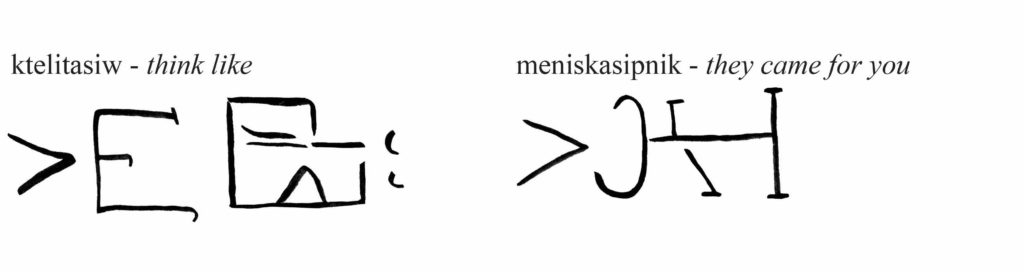

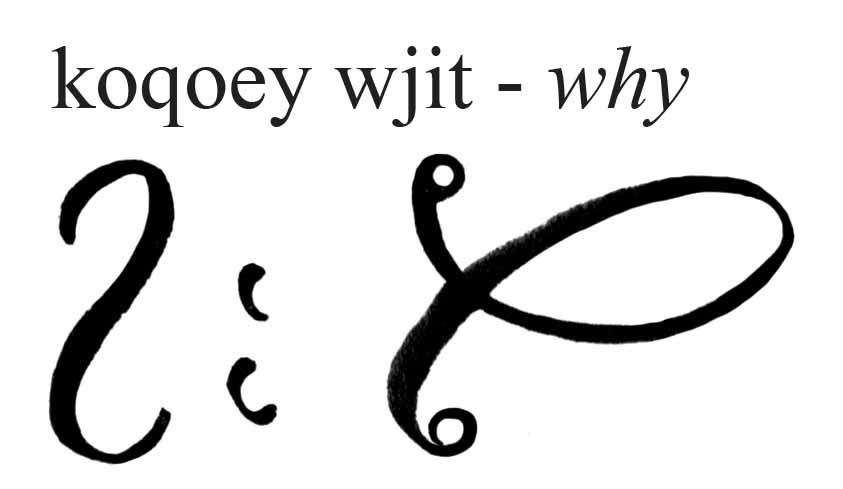

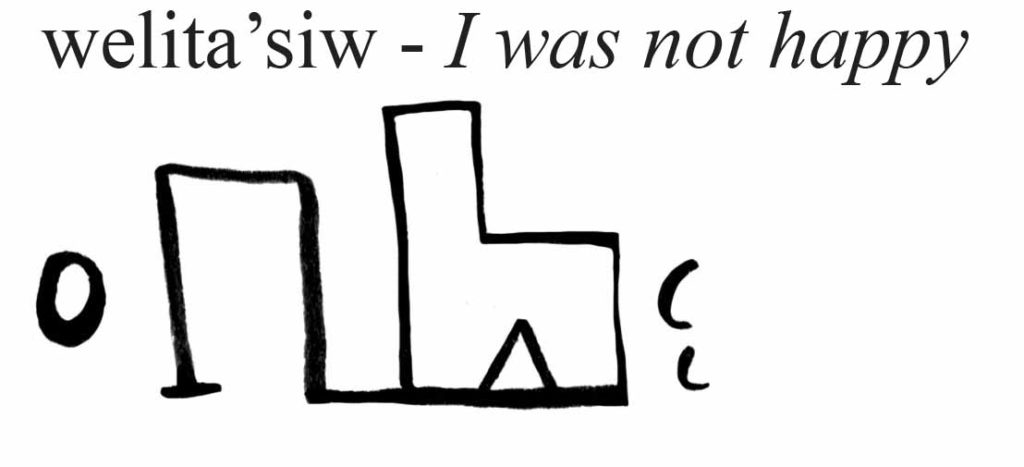

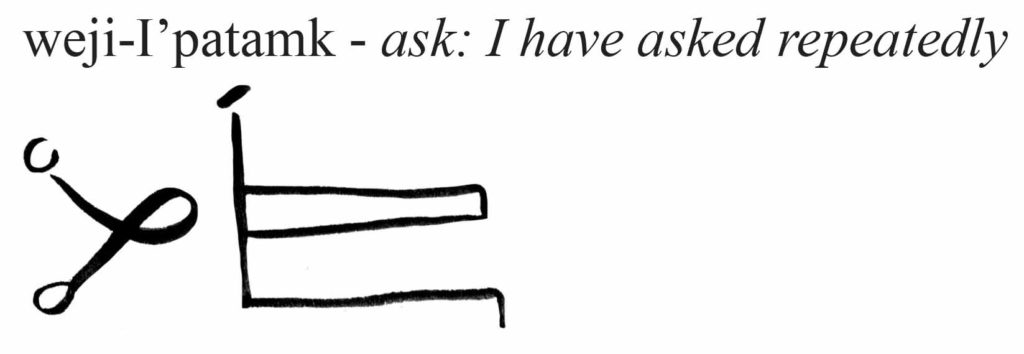

Editor’s Note: Published in three installments, this intervention by L’nu interdisciplinary artist, poet, and scholar Michelle Sylliboy offers an Indigenous perspective on the colonial archive. In Part I: Reclaiming Komqwejwi’kasikl, Sylliboy presented the poetic gift she received from her ancestors that launched her creative journey reclaiming the komqwejwi’kasikl writing system from French missionary Chrestien Le Clercq’s Nouvelle Relation de la Gaspésie (Paris, 1691). In this second part, Sylliboy continues her poetic work around this painful text by engaging with the archive of Indigenous-settler relations as a source of ongoing trauma. Using autobiographical creative inquiry, she examines the role of the Nm’ultes knowledge system in her healing process and reflects on her participation in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that took place in Canada between 2007 and 2015.

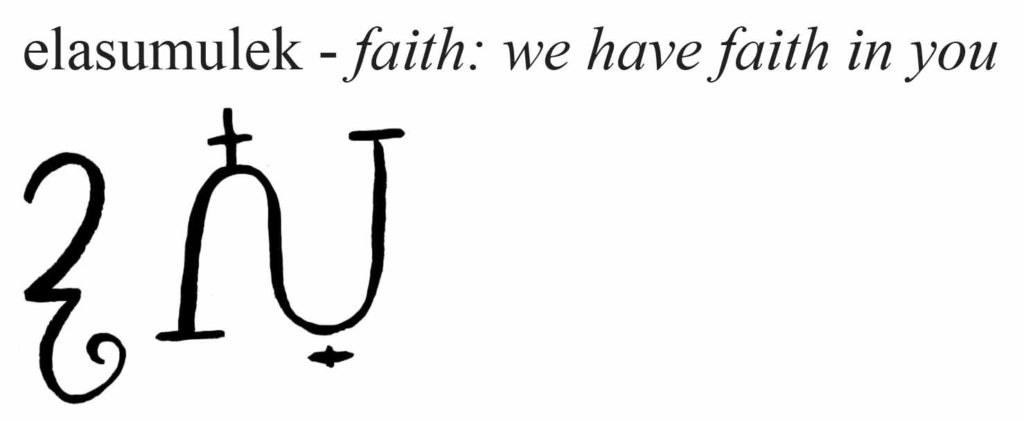

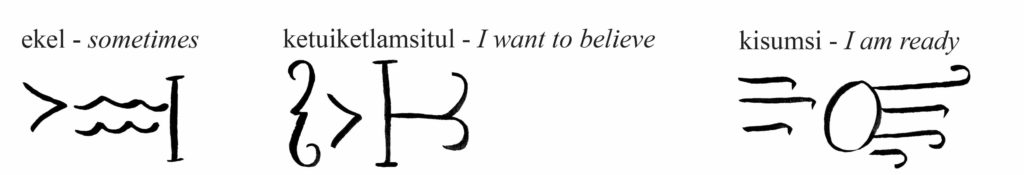

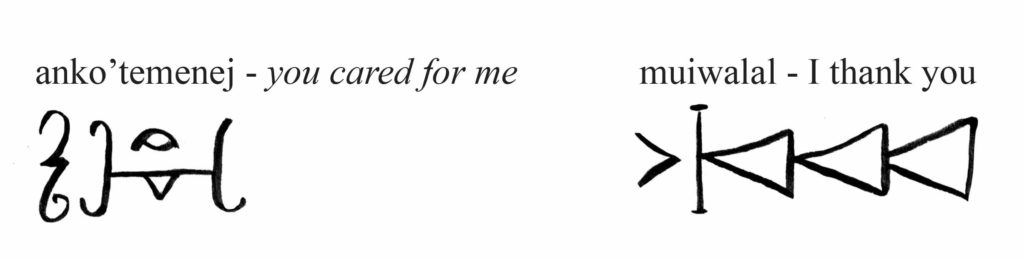

Michelle Sylliboy, Muiwalnek / We Thank You / Nous vous remercions, 2019. Wasoqitestaqn / Digital photography / Photographie numérique, 86.4 x 58.4 cm. © Michelle Sylliboy

Nm’ultes is the creative inquiry compass on this journey you are about to partake in. For me, Nm’ultes is divided into four parts. It simultaneously connects me to the past, present, and future, and ontologically to my biological mother as I am the fourth child.

Nm’ultes one began when I was removed from my mother’s care. This encounter was the first separation from my family, a traumatic displacement of mother and baby, a move I was too young to remember but that later inspired a child to look at komqwejwi’kasikl scrolls in her new parents’ home and at church in We’koqmaq, Nova Scotia, on L’nuk territory.

Nm’ultes two took place in Toronto, on Mississauga territory, in 1988. My first decolonizing act was to silk-screen the komqwejwi’kasikl language onto t-shirts. Disconnected from my adoptive family, land, and people, I felt the birth within me of a deliberate desire to reconnect with my people and culture. This was also the first time I learned about a seventeenth-century priest making deliberately false claims about inventing the komqwejwi’kasikl hieroglyphic language to remove my L’nuk people from their history.

Nm’ultes three took place in art school on Coast Salish territory, again away from my family, people, and landscape. During my undergraduate years, a subconscious intention to understand my personal trauma began to take shape. I had no immediate recognition that my personal history was connected to the history of residential schools.

Nm’ultes four brings me to the present, after living away from my people for long periods of time and researching L’nuk history since the seventeenth century. Each developing stage of my life has slowly opened my eyes to the impacts of my personal trauma, and to how I engage with academic discourse. My awakening begins with my rediscovery of the komqwejwi’kasikl language. It was my ancestors’ children who showed its symbols to French Missionary Chrestien Le Clercq.[1]

It’s important to acknowledge how these four segments unlock the missing pieces of a Nm’ultes journey. I am a poet who misunderstood for many years how her healing would emerge from Nm’ultes and intersect with elders’ teachings.

Philosophical Differences Colliding and Connecting

I was raised within the L’nuk worldview, which regards everything as interconnected. According to the L’nuk theory of knowledge, evidence or proof of existence only occurs when we are ready to receive the truth, in stark contrast to Western ontological and epistemological perspectives. The academic journey that led me to studying the komqwejwi’kasikl language and gifted me the opportunity to write my poetry confirms my L’nuk worldview. I have also found encouragement and confirmation in an unlikely source, Spinoza’s Proposition XIV in part II of the Ethics: “The human mind is capable of perceiving a great number of things, and is so in proportion as its body is capable of receiving a great number of impressions.”[2] In this view, inspiration is an infinite source that allows us to push the boundaries of what we can achieve.

As my Nm’ultes journey evolves, so does my unresolved and self-imposed exile, which I neglected to acknowledge at the start of my academic journey. Was this neglect deliberate in the sense that my Nm’ultes was subconsciously avoiding the issue for a reason? “I” didn’t know about this, but some part of me, my Nm’ultes part, knew that this exile was the way for now. My traumatic past has always impacted my life and taken me to many places, but now I am at a place where my life journey has become clear.

I was meant to learn about the komqwejwi’kasikl language, to travel across Canada to Coast Salish territory, away from my people’s L’nuk traditional territories. Only now is the conduit role I am playing as an artist and as an L’nu beginning to make sense of the way my life has unfolded. Nm’ultes and the komqwejwi’kasikl language share a displacement within the L’nuk narrative in the same way I share a displacement with my past.

While studying at Langara College and at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, both in Vancouver, British Columbia, visual art became a focal medium to unravel the harm inflicted on me when I was younger. In effect, I was using art school as therapy to address unresolved trauma. This was very confusing, as the initial development of my Nm’ultes inquiry occurred with no awareness or knowledge of residential school history. My memories of this period are vague. The gaps would only make sense later as an effect of intergenerational trauma.

During my first two years of art school, a Pandora’s box of unrecognizable trauma opened. A personal Nm’ultes story emerged, but nothing made sense at first. During this freeing process, I had so many questions to pose to the universal god-force, a force that swept me away from my family, people, and homeland on multiple occasions. Every time my artistic impulse wanted to manifest in this world, it lashed out with anger and frustration. I had no references or parental guides explaining what was happening within me.

It was the 1990s, and I actively searched for answers, but found no resources on what I would later learn were the impacts of intergenerational residential school trauma, certainly nothing that would help me understand how the past had contributed to my self-imposed exile. The TRC hadn’t even been formed yet. However, the god-force was plotting, keeping busy, to protect or unravel a Nm’ultes connection. As the years went on, I read and met many First Nations poets and future scholars, such as the late Lee Maracle and the late Ethel Gardner. They laid the groundwork, planted seeds, and introduced me to the writings of Indigenous scholars such as Dr. Marie Battiste, whose book Protecting Indigenous Knowledge made an Nm’ultes impression.[3] Māori scholar Linda Tuihai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies changed the way I looked at education and shifted my worldview as an Indigenous woman.[4] The late poets Connie Fife and Rita Joe, who wrote this poem titled “Justice,” inspired my poetic urge to write about the truth:

Justice seems to have many faces

It does not want to play if my skin is not the right hue,

Or correct the wrong we long for,

Action hanging off-balance

Justice is like an open field

We observe, but are afraid to approach.

We have been burned before

Hence the broken stride

And the lingering doubt

We often hide

Justice may want to play

If we have an open smile

And offer the hand of communication

To make it worthwhile

Justice has to make me see

Hear, feel.

Then I will know the truth is like a toy

To be enjoyed or broken[5]

Over time, these writers educated me about the legislated trauma inflicted on First Nations people since the birth of colonization. Its negative impacts were colossal, far bigger than my personal frustrations or my loss of family! Yet, despite the education I received from my elders and friends, I felt that something was festering in the back of my mind, an Nm’ultes story waiting to be unleashed. For many years after I began my journey with the komqwejwi’kasikl language in 1988, Le Clercq’s claim to have invented the komqwejwi’kasikl hieroglyphs gnawed at me: “Our Lord inspired me with the idea of them the second year of my mission.”[6]

I sensed even then a missing link, something about the expected healing that needed resolution and that wanted to manifest in order for me to move forward. However, I placed this story into the Nm’ultes box until I was ready to acknowledge it without feeling overwhelmed by horror and grief.

The devastating impacts of residential schools are still being felt across Canada. Communities are afflicted with trauma and suffering from lack of infrastructure, be it food, water, shelter, education, or family connections—essential tools to heal. As the TRC acknowledged:

Residential schools are a tragic part of Canada’s history. But they cannot simply be consigned to history. The legacy from the schools and the political and legal policies and mechanisms surrounding their history continue to this day. This is reflected in the significant educational, income, health and social disparities between Aboriginal people and other Canadians. It is reflected in the intense racism some people harbor against Aboriginal people and in the systemic and other forms of discrimination Aboriginal people regularly experience in this country. It is reflected too in the critically endangered status of most Aboriginal languages…. The impacts of the legacy of residential schools have not ended with those who attended the schools. They affected the Survivors’ partners, their children, their grandchildren, their extended families, and their communities.[7]

I once dreamed hundreds of whales stood up in the ocean to honor me in their present world. Standing in utter shock was my spirit, alone on a beach. As I maneuvered myself to get closer, one of the whales began walking towards me on the beach and transformed into a beautiful woman who said I was on the right path with my writing, that it was her nudging me in the right direction. It felt as though the whales stayed with me the entire night. When the dream did change, I saw myself driving a scooter to an art show, which looked like a circus. In every dream I had that unforgettable night, powerful women were my mentors.

Nm’ultes Unearthed

The Nm’ultes analogy is to look forward to seeing someone later. In my case, I sought family, homeland, and healing, an unexpected process that only made sense during and after the 2013 TRC conference in Vancouver. These national events were held in different regions of the country to promote awareness and public education about the residential school system and its impacts. In Vancouver, I kept asking myself why its impact on me had been so painful. I had gone to the same conference in Halifax, where I had spent several years as a homeless teenager. I have no doubt that my elder, the late Cecil Condo, who sent me to the TRC in Halifax, knew I needed to go. It was not like any other gathering I had attended. After several days of crying, releasing emotions around memories of a homeless past, I felt alone and lost in a city I had despised for many years. It was a strange, haunting experience to be where I used to fall asleep every night on a street or in one of the heated walkways connecting downtown Halifax. Over thirty years later, there I was, staying at the same hotel in which I used to figure out ways to sleep undetected, praying each night to wake up the next day.

Every day, I would attend the TRC, and, every night, I would walk back and cry for hours in my hotel room. Despite there being therapists and healers available for anyone who attended, I was too numb to ask for help. I now understand that numbing is part of the impact of trauma:

When a person is completely powerless, and any form of resistance is futile, she may go into a state of surrender. The system of self-defense shuts down entirely. The helpless person escapes from her situation not by action in the real world but rather by altering her state of consciousness. Analogous states are observed in animals, who sometimes ‘“freeze” when they are attacked. These are the responses of a captured prey to predator or of a defeated contestant in battle…. These alterations of consciousness are at the heart of constriction or numbing, the third cardinal symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder.[8]

I am a child of a residential school survivor, and, on a bad day, I feel as though I have no cognitive tools for survival. Rather than speaking to a healer or a therapist, I instinctively knew it was important to tell my story and have it recorded. I thought that it would complete my healing ceremony. I was wrong.

I’m not sure where the Commission stored the recordings they took from the survivors and children of survivors at every TRC event. I know they are part of archives whose future has recently been debated by people who have no right to delete my story. Erasing the past and changing the narrative will not change their impact.

The conference in Halifax forced me to meet my demons and fears. I knew I was no longer homeless. I knew I was safe and okay as an adult. Yet my healing had not begun. I was not ready. The Nm’ultes education paradigm kicked in, and my body sent me back to Vancouver, a city that has protected and shielded me for many years. The same city first initiated my healing through sobriety at age twenty-two, and it was there that higher education degrees began to present themselves as options. Vancouver is also where I first discovered love. Before coming to Vancouver, I could not understand what it meant to love someone special or to allow anyone in, even as a friend. Love is one of the first things children of survivors struggle to say out loud because they feel it has no meaning. I have often heard survivors and children of survivors say they have struggled with understanding love. Through its mountainous surroundings and endless ocean energies, the city opened me to love; that much I know about my Nm’ultes teachings in Vancouver.

Michelle Sylliboy is Assistant Professor in the Art Department and in the School of Education at St. Francis Xavier University, Nova Scotia, Canada on unceded L’nuk territory

Part 3 will be published later in 2022.

[1] For a discussion of the cultural appropriation of the komqwejwi’kasikl script by Chrestien Le Clercq, see my “Artist’s Notes: Nm’ultes is an Active Dialogue I: Reclaiming Komqwejwi’kasikl,” Journal18 (June 2022), https://www.journal18.org/6399.

[2] Baruch Spinoza, Improvement of the Understanding, Ethics and Correspondence, trans. R. H. M. Elwes (London: M. Walter Dunne, 1901), 94.

[3] Marie Battiste and James Youngblood (Sa’ke’j) Henderson, Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: A Global Challenge (Saskatoon: UBC Press, 2000).

[4] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 1st ed. (London: Zed Books, 1999).

[5] Rita Joe, Song of Rita Joe: Autobiography of a Mi’kmaw Poet (Wreck Cove, NS: Breton Books, 2011), 117-118.

[6] Chrestien Le Clercq, New Relation of Gaspesia: With the Customs and Religion of the Gaspesian Indians, transl. W. F. Ganong (Toronto, ON: The Champlain Society, 1910), 131.

[7] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Honoring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015), 135-136. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

[8] Judith Lewis Herman, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence, from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 42.

Cite this note as: Michelle Sylliboy, “Artist’s Notes: Nm’ultes is an Active Dialogue II: An Autobiographical Creative Inquiry,” Journal18 (September 2022), https://www.journal18.org/6471.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.