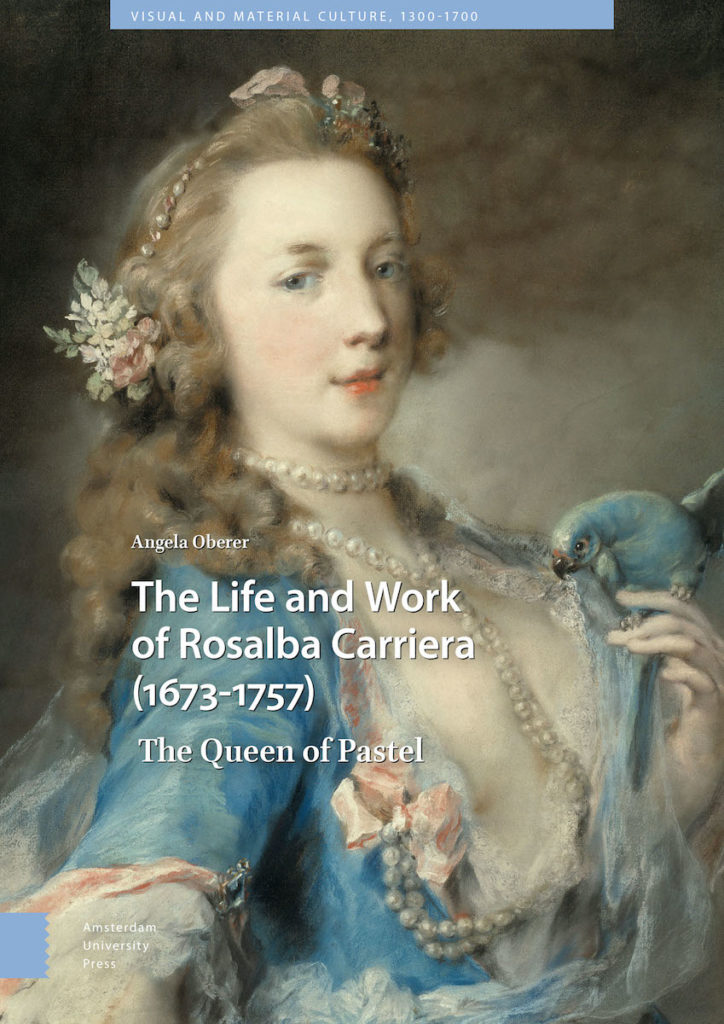

Angela Oberer, The Life and Work of Rosalba Carriera. The Queen of Pastel (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020). 326 pages. ISBN: 9789462988996

Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757) is a celebrated name in the eighteenth-century art world, with a well-established place in Grand Tour mythology for attracting clients to sit for their portraits in Venice. Current understanding—in Anglo-American scholarship at least—consists of illuminating but partial viewpoints. Noteworthy short pieces have been published, for example on her biographies (Julia Dabbs), her well-documented visit to Paris at the height of John Law’s fame (Kathleen Nicholson), and on the display of her pastels in cabinets (Shearer West).[1] Carriera’s distinctive contribution to pastel is recorded, and regularly updated, in Neil Jeffares’s invaluable online Dictionary of Pastellists. Beyond this, a fully holistic evaluation of Carriera’s achievements has hitherto required a mastery of German and French as well as Italian. Bernardina Sani’s monograph (published in 1988, updated 2007), written in Italian, remains a point of reference.[2] Difficulties transporting and displaying pastel, and the sheer patience required to engage with Carriera’s other medium of miniature, have combined with stubborn old misogyny: outside of Venice, the only monographic exhibition ever devoted to her was in Karlsruhe in 1975.[3]

Angela Oberer’s book is welcome, therefore, as the first comprehensive English language monograph on Rosalba Carriera. It sets out the full facts of her life and career with reference to contemporary documents, analyzes key works of art, and is informed by feminist art history of recent decades. A recurring theme is how the artist transcended the disadvantages of her gender, particularly her minority status as an unmarried woman. This was something she had in common with only 10% of European women and was even rarer in artistic circles. Carriera was supported in her career through good family relationships with her mother and sisters, and cultural connections with other professional women such as the writer and translator Luisa Bergalli Gozzi.[4]

The artist’s early years as a miniaturist are addressed in the first chapter. Although risky, it was a shrewd choice by Carriera to profit from the dearth of miniaturists in the city and avoid the crowded, male-dominated market for altarpieces. In addition to finding customers, she gained the recognition of the art establishment, becoming a member of the Accademia di San Lucca in Rome in 1705. Oberer shows that, in her mythological pictures, Carriera displayed the erudition of a history painter, working with textual sources and artistic predecessors, and subtly reframed subjects in order to stress female agency. For example, adapting a composition by Veronese of Venus and Adonis where the male appears in hot pursuit, she transformed the gesture in her Venus and Cupid (formerly Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden) to put Venus firmly in charge of her own desirability. Working with the quintessential elements of the Venetian School, Carriera catered to a market for carefully packaged eroticism, creating intimate visual fantasies, mythologies based on Ovid or Tasso, a young female gardener (Bayerishes Nationalmuseum, Munich), or a woman at her toilette (Cleveland Museum of Art).

Staying with miniature but increasingly turning to pastel, Carriera was able to sustain a profitable portrait business. Correspondence shows how she carefully managed her clientele before, during, and after their visits to her studio, and used to her advantage pastel’s facility for rapid execution. She developed an international reputation from her base in Venice, thereby avoiding the more precarious itinerant lifestyle of many of her (male) fellow Venetians who were obliged to tour the courts of Europe. The Paris sojourn was an exception, brought about by the persistent calls of French financier and art collector Pierre Crozat; later efforts to broker an English visit on the back of the French one came to nothing. Germany, and later Vienna, were significant markets for the artist, especially Dresden under Augustus II and his son Frederick Augustus II, as these Saxon rulers sought to consolidate their power across Europe through conversion to Catholicism and then through the acquisition of abundant artworks from Venice in particular. Frederick Augustus became a great enthusiast of Carriera’s work, and his son Frederick Christian travelled incognito to Venice for his portrait, taking advantage of the occasion to buy up her entire studio. The resulting “Rosalba cabinet” in Dresden, where eventually over 150 of her pastels were brought together, was one of the highlights of the city’s art collections and, despite World War II and other losses, remains the most significant repository of her work.

Managing her international business involved attending to clients’ concerns about shipping. The artist’s correspondence contains material details of packaging and delivery, and much back and forth about whether to use glass and what type. Sometimes clients requested a bespoke box, or several, in which to place their artworks. An order for the Elector Palatine in Düsseldorf required in addition, several layers of paper and a filling of semolina. Often items were packed in a diplomat’s luggage in preference to trusting the postal service. Charging significant prices for her work, Carriera invested her profits with the help of her banking connections, eventually becoming one of the wealthiest Venetian artists of her time.

Chapter 5 contains an appraisal of Carriera’s oeuvre in pastel. She produced portraits, character studies, and allegories, and quite often the boundaries between these different types of artworks are blurred. Here it would have been beneficial to see wider contextualization of works variously known as ‘teste’ and the role of fantasia and capriccio in Venetian art.[5] Alongside Carriera, precursors such as Giorgione and Titian, as well as influential face-painters of her day like Giovanni Battista Piazzetta and the Tiepolos, were also skillful manipulators of the human form independently of resemblance, capturing whimsical and fleeting desires: intimate performances of emotion, texture, costume.[6]

In the same chapter Oberer offers an interesting account of Carriera’s depictions of beautiful women and her continuation of a tradition of “galleries of beauty” dating back to the sixteenth century. She argues plausibly that the works’ uniform quality or “sameness” can be accounted for in terms of demand among Carriera’s clients to achieve a distinctive “look.” The term isn’t used but the description of fulfilling a contemporary desire to “be a Carriera” is akin to modern-day branding.

There is a body of material among Carriera’s life and work that lends itself to queer interpretations, not least a caricature by Carriera’s good friend Anton Maria Zanetti (Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice) showing her grinning widely, square-jawed, with a proliferation of facial stubble. This image could be linked to the androgyny of the artist’s self-portrait as Winter (Fig. 1), which itself is not unlike studies of old age by Balthasar Denner and Giuseppe Nogari, or her rather feminized Apollo (State Hermitage, St Petersburg). Carriera’s relationship with her protégée and pupil Felicitia Sartori was an intense one that generated an unmistakably erotic portrait in the Uffizi.

One of the most absorbing sections of the book is found near the end, where evidence is used to describe Carriera’s house on the Grand Canal that served as living space, artist’s studio, salon (in the full sense of eighteenth-century sociability), and shop window for her art. Records show that Carriera acquired luxury products, including chinoiserie and coffee. This hybrid use of space, known to be a feature of other European artists’ living and working arrangements at the time, was apparently rare in Venice. This account could have had greater resonance if it had been placed earlier in the book as a means to understand Carriera’s success in drawing influential people into her orbit. In fact, chapter 8’s wider theme of self-fashioning (which includes analysis of her self-portraits), would arguably have worked better if it had been integrated into the book as a whole. That way the biography could have been construed more actively as a series of choices or negotiations.

Carriera appears to have been a circumspect person who didn’t emote or strike poses in her private correspondence; the diary of her stay in Paris is succinct and factual.[7] At times Oberer’s study feels a bit too trusting of the artist’s studied self-possession and, again, this is partly down to organization of the material. If the artist’s rise to fame and fortune appears quite easy in the early chapters, then there is a subtext of disappointment and frustration in the correspondence, duly observed in chapter 6, which focuses on her identity as a spinster. Better integration of what must have been daily snubs and setbacks into the weft of Carriera’s career might have provided scope for reflection on possible strategies and counter-attacks. As Kathleen Nicholson has argued (admittedly in somewhat speculative fashion), Carriera’s dealings with the Paris academy may well have involved a proactive riposte to misogyny.[8]

Overall, however, Oberer deserves credit for her careful, painstaking revisionism. She has succeeded in assembling, mapping, and making accessible Rosalba Carriera’s substantial international networks and accounting for her numerous artistic achievements. As the author modestly points out, there is further work to do in understanding the import of this significant female artist. Together with the forthcoming edited translation of documented sources on the artist by Catherine Sama and Julia Kisacky (Toronto, “Other Voice” series), J18 readers have new tools at their disposal.

Melissa Percival is Associate Dean of Global (Humanities), and Professor of French, Art History, and Visual Culture at the University of Exeter

[1] Julia Dabbs, “Anecdotal Insights: Changing Perceptions of Italian Women Artists in Eighteenth-Century Life Stories,” Eighteenth-Century Women 5 (2008), 29-51; Kathleen Nicholson, “Having the Last Word: Rosalba Carriera and the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, 52:2 (2019), 173-177; Shearer West, “Secrets and Desires: Pastel Collecting in the Early Eighteenth Century Dresden Court,” Oxford Art Journal, 38:2 (2015), 209-223.

[2] Bernardina Sani, Rosalba Carriera 1673-1757: maestra del pastello nell’Europa “ancien regime,” (Turin: Umberto Allemandi & Co, 2007).

[3] For a list of exhibitions, see Neil Jeffares, “Rosalba Carriera,” Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, London, 2006; online edition: http://www.pastellists.com/articles/carriera.pdf, 4n2, updated 23 May 2021.

[4] See Catherine Sama, “‘On Canvas and on the Page’: Women Shaping Culture in Eighteenth-Century Venice,” in Paula Findlen, Wendy Roworth, and Catherine M. Sama eds., Italy’s Eighteenth Century: Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 125-150; 383-393.

[5] See for example Teste di fantasia del settecento veneziano, exh. cat. (Venice: Palazzo Cini, 2006); Bortoloni, Piazzetta, Tiepolo: il ‘700 veneto, exh. cat. (Rovigo, Pinacoteca di Palazzo Roverella, 2010).

[6] See Figures de fantaisie, catalogue to an exhibition at the Musée des Augustins, Toulouse (Paris: Somogy, 2015).

[7] The journal was published in French 1793 and 1865. For the latter, please see: Rosalba Carriera, Journal de Rosalba Carriera pendant son séjour à Paris en 1720 et 1721, trans. Alfred Sensier (Paris: J. Techener, 1865). Accessible at: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k102049h.image. For the English translation, please see: Neil Jeffares, “Rosalba Carriera’s Journal,” Pastels & Pastellists, http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/Carriera_journal.pdf.

[8] Nicholson, “Having the Last Word.”

Cite this note as: Melissa Percival, “’The Life and Work of Rosalba Carriera’: A Review,” Journal18 (June 2021), https://www.journal18.org/5771.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.