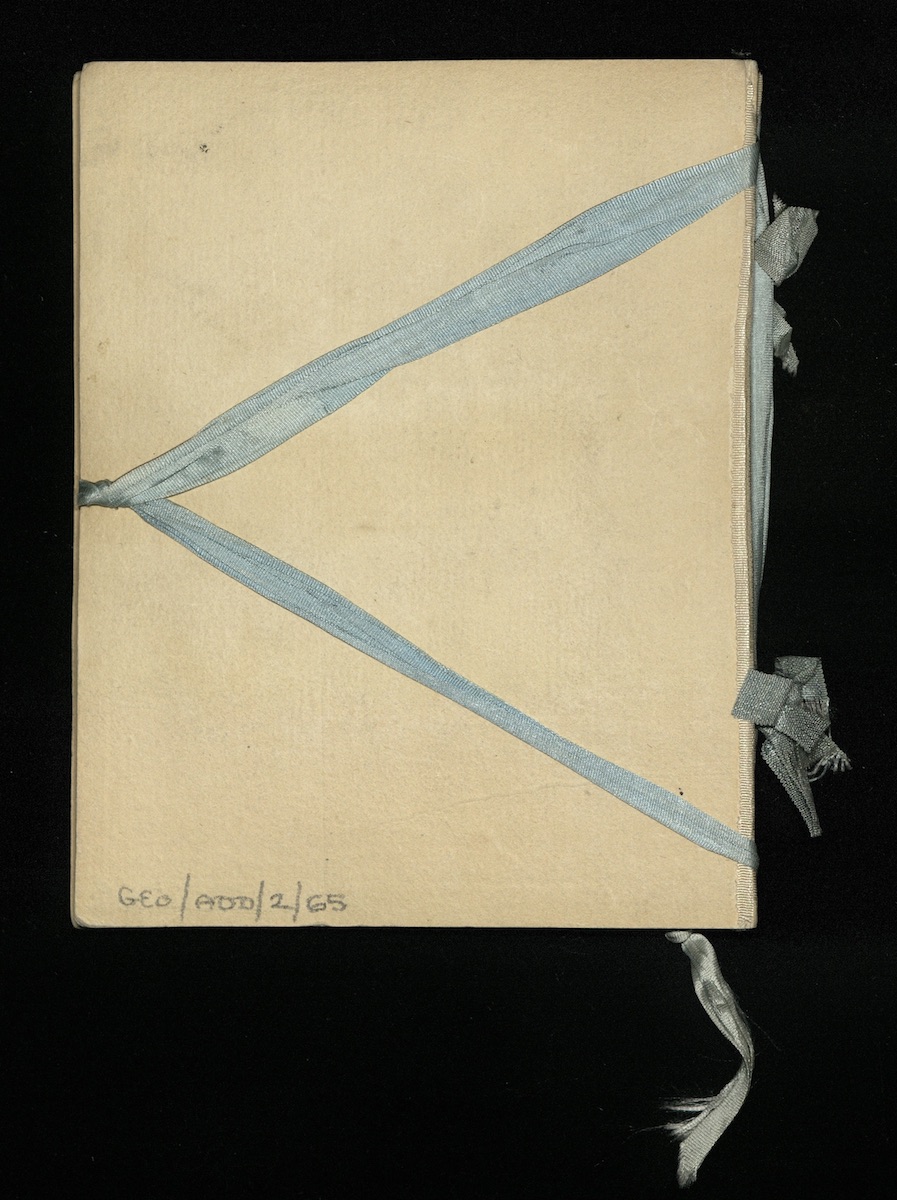

Fig. 1. Mary Delany, Front board of album of découpage tied with blue ribbon, 1781. RA/GEO/ADD/2/65. Image: The Royal Archives, Windsor / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018.

An album of découpage created by the artist, writer, and Bluestocking Mary Delany sometime before the winter of 1781 has been strangely ignored in the scholarly record (Fig. 1). Gifted to George III’s consort, Queen Charlotte, it comprises twenty pages decorated with 114 individual cut-paper designs on a blue ground. These colorful designs, which range from intricate and realistic botanical representations to more abstract decorative motifs, represent a hybrid manifesto of artistic ideas. This essay argues for the album’s importance in developing ongoing conversations about Delany’s methods and materials, as well as the function and performance of such objects within social, creative, and emotional relationships. Only a brief mention of the album appears in Ruth Hayden’s seminal work Mrs. Delany and Her Flower Collages, recording that “the recent appearance at Windsor Castle of a booklet of silhouettes cut by Mrs Delany” gives proof of the “mutual esteem” between Queen Charlotte and the artist.[1] Held in the Royal Archives, the album was likewise absent from the 2009 Yale Center for British Art exhibition Mrs. Delany & Her Circle that constituted a momentous gathering of Delany’s works as well as a substantial body of scholarship, in the accompanying catalogue, greatly advancing our understanding of her social world and working methods.[2] Recently digitized as part of the ground-breaking Georgian Papers Programme, this album now needs to be situated within Delany’s vast corpus and, more broadly, within practices of paper-cutting at the royal court and throughout elite circles of the period. In this brief note I propose an initial reading of the album as part of a series of exchanges between Queen Charlotte and Delany, providing insight into their creative lives, the conversational and collaborative nature of domestic handicrafts, and the role of such materials in enacting and confirming elite female friendships. Although the album has remained absent from scholarship, close study of it can provide crucial insight into the economies of emotional and tactile exchange between elite women, and the potency of crafting as affective work.

Delany was a renowned artist. She was a close companion of Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, duchess of Portland (1715-1785), and spent several years living at the duchess’s country residence of Bulstrode Park in Buckinghamshire, where she contributed to the duchess’s famous museum and regularly included items from its natural history collections in her botanical paper mosaics.[3] Delany was first invited to reside at Bulstrode after the death of her second husband, Patrick Delany (1686-1768). In May 1768, the duchess told Delany’s niece that “she could spend every summer with her friends [at Bulstrode], who would be so happy to have her company.”[4] In the dedication to her famous Hortus Siccus (the albums of flower mosaics that have secured her artistic legacy) of 1779, Delany wrote of the duchess’s role in supporting her art work, setting a precedent for paper albums as the material sites and spaces of elite female friendship:

To her I owe the spirit of pursuing it with diligence and pleasure… my heart will ever feel with the utmost gratitude, and tenderest affection, the honour, and delight I have enjoy’d in her most generous, steady, and delicate friendship, for above forty years.[5]

The duchess also played an important role in the establishment and development of friendship between Queen Charlotte and Delany, often facilitating or bearing witness to their material exchanges. Delany first exhibited her work to the queen during a royal visit to Bulstrode in 1776, where, as she later wrote, the informality of the gathering allowed for the transcendence of social rank and the establishment of a reciprocal friendship:

The King desired me to show the Queen one of my books of plants: she seated herself in the gallery; a table and the book laid before her. I kept my distance till she called me to ask some questions about the mosaic paper-work.[6]

In the decade that followed their first meeting, Delany and Charlotte passed gifts between Bulstrode and Windsor, collaborating on domestic projects and developing an aesthetic language through which their emotional and creative bond was eloquently expressed and recorded. My aim is to situate Delany’s album of découpage within this series of object exchanges, reading handicrafts, collage, and paper-cutting as tactile representations of female conversation. How did the exchange of such materials, freighted with emotional and intimate meaning, function as part of a private currency used to confirm friendship? And how can it be understood within cultures of collecting at both the royal court and Portland’s museum? Tracing material and social connections between the two sites provides some answers and helps us understand how the album worked textually, as both narrative display and portable directory of a private iconography.

Previously, historians have considered Queen Charlotte’s friendships in the context of the monarchy, and the restrictions placed on the queen in terms of social interaction and public performance. As Clarissa Campbell-Orr has suggested, “the Queen was immensely constrained by virtue of her role… [and] needed private moments of respite” and “opportunities for seclusion” in order to cultivate friendships and enjoy domestic life.[7] Bulstrode was one such site, where the duchess’s famed museum provided diversion for the royals and context for their own collecting and connoisseurial pursuits. At Bulstrode, the queen was invited to engage with the intellectual and artistic work of the duchess and her guests. The fact that “Delany held no position at Court may well have been part of her attraction for both the King and Queen, for they knew they could relax in her company, free from any officialdom.”[8] Campbell-Orr has made a case for Delany’s autobiography as an important source for understanding Charlotte and her domestic activities away from public performance. She even suggests that, for both the king and queen, Delany was akin to a grandmother; Charlotte has lost her own mother prior to her marriage, whilst for the king, Delany may have recalled the earlier times of his parents and even his grandfather.[9]

Whilst it is impossible to dismiss the distance in rank between Delany and Queen Charlotte, this essay positions their relationship, one of mutual respect as well as artistic collaboration, within a context of material exchange conducted primarily in the domestic environments of the two women’s worlds that allowed for the transgression of the strict boundaries away from the highly visible and ritualistic aspects of court life. Within such spaces, the gifting and receiving of objects, usually situated within institutions of friendships, often embodied conversational, emotional and intellectual exchange alongside the material. As Elizabeth Eger argues, Bluestockings “expressed their intellectual ambitions through the more conventional media of female ‘accomplishment’, such as cut-paper work, needlework, and feather and shell work.”[10] Similarly, Johanna Ilmakunnas has noted the role of these productions as communicative and affective tools, suggesting that “the objects women made embodied representations and emotions of their makers, carrying them further to those who received and used the objects, visualizing through them at least some of the emotion embedded in their making.”[11]The role of friendship amongst elite circles was paramount in espousing creative values, and in communicating and negotiating the social order. For elite women, in particular, it provided a framework in which they could prescribe and administer behaviors and moral values. For example, on 11th February 1791, Princess Elizabeth wrote to her brother, Prince Augustus on the subject of friendship. In her letter, she defined it as “one of the greatest if not the greatest blessing of life to speak well of one’s friend.”[12] Certainly, intimate friendship amongst elite women was highly valued, both at court and in society more broadly. The exchange of craft works and other objects between them within the context of gifting and a domesticated sociability further facilitated and sustained elite female friendship. The album made for Charlotte and the pocketbook for Delany stand as evidence of cross-site and cross-rank collaboration and the development of an artistic and aesthetic language formulated in the materials of women’s productions and defined within practices of friendship exchange.

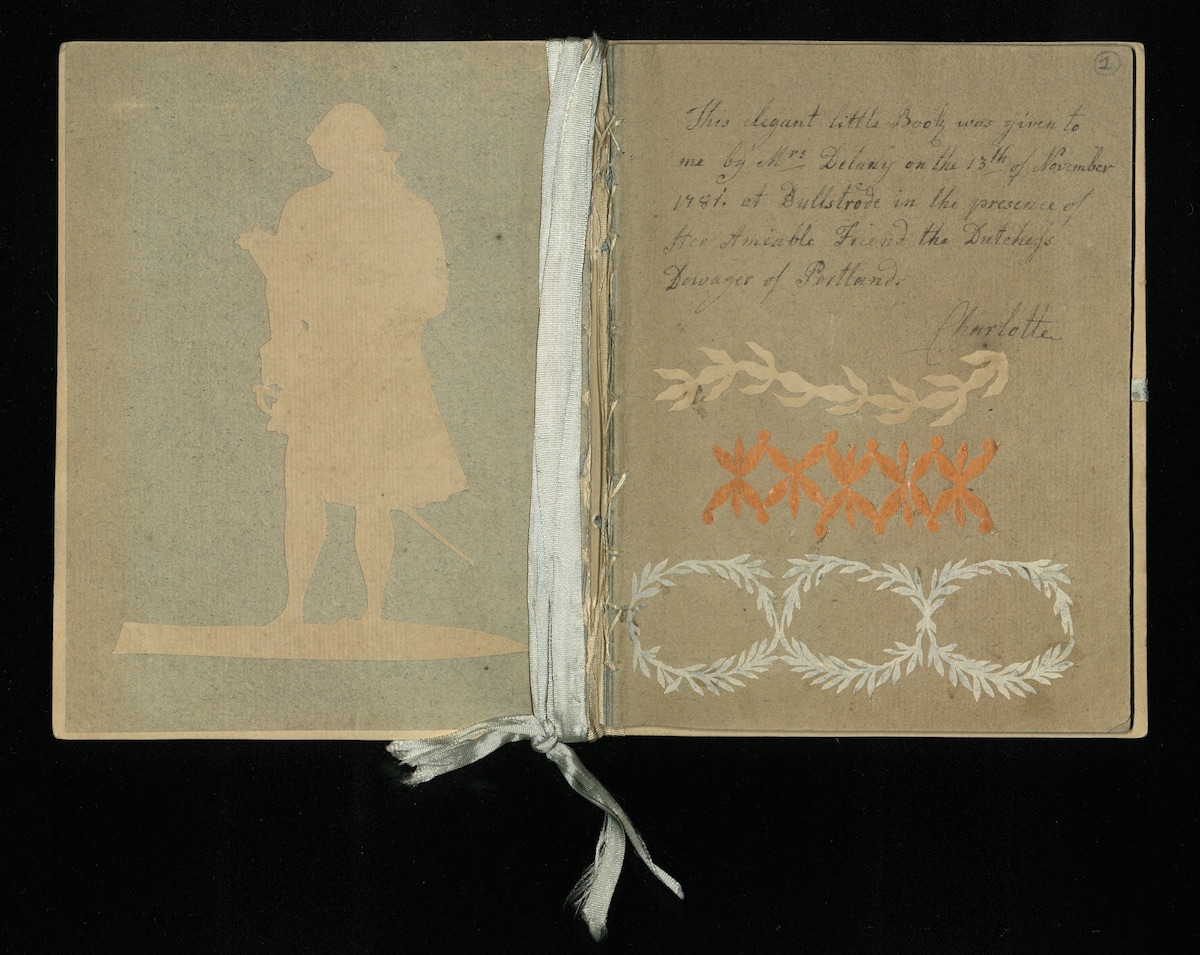

Fig. 2. Mary Delany, First page of album with dedication written in Queen Charlotte’s hand, 1781. RA/GEO/ADD/2/65. Image: The Royal Archives, Windsor / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018.

Delany’s Album and Charlotte’s Pocketbook

Inside the first page of the album is a dedication, written in Charlotte’s hand (Fig. 2): “This elegant little Book was given to me by Mrs Delany on the 13th of November 1781 at Bullstrode [sic] in the presence of Her Amiable Friend the Dutchess [sic] Dowager of Portland.”[13] On 13 November 1781, the king and royal family attended a hunt at Gerrard’s Cross, a few miles outside of the duchess’s estate. During the course of the day, the duchess and Delany received the queen at Bulstrode, where Delany presented her with the book of découpage. Later relating events to her niece Mary Port, Delany described how the queen, princesses and ladies-in-waiting had absconded from the overtly masculinized events of the hunt in order to attend the duchess within the feminized, private spaces of Bulstrode.

The Duchess of Portland returned home in order to be ready to receive the Queen, who immediately followed, before wee [sic] could pull of [sic] our cloaks! We receiv’d her Majesty and the Princesses on the steps at the door, but she is so gracious that she makes everything perfectly easy. We got home a quarter before eleven, and the Queen staid till two.[14]

Although Delany gives no indication of her presentation of the album to the queen during this visit, a note written by Mary Hamilton the day after the hunt gives a glimpse into the conversation and activities enjoyed during the queen’s time at Bulstrode. Writing from the Queen’s Lodge, she reports to Delany that “the King wishes so much to have the pleasure of seeing her Grace and his ‘dear Mrs. Delany’ (his own expression, I assure you).”[15]

Fig. 3. Queen Charlotte, Embroidered needlework pocket-book containing stainless steel and mother-of-pearl tools and gifted to Mary Delany, 1781. Satin, colored silks and enamelled gold, 10 7/8 x 9 7/8 x 5/8 inches (open). Image: Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

A month after Delany’s presentation of the album to the queen, Charlotte sent a letter from Windsor to Bulstrode with a precious gift, a small pocketbook, embroidered in cream-colored silk by the queen with metal sequins and an enamelled clasp, and containing ten sewing tools made from mother-of-pearl and steel (Fig. 3).[16] The letter covering the pocketbook in Charlotte’s hand read:

Without appearing imprudent towards Mrs. Delany, and indiscreet to her Friends who wish to preserve her as her excellent qualities well deserve, I cannot have the pleasure of enjoying her company this Winter which our amiable Friend the Dutchess [sic] Dowager of Portland has so frequently and politely indulged me with during the Summer. I must therefore desire that Mrs. Delany will wear this little Pocket-Book in order to remember at times, when no dearer Person’s [sic] are present, a very sincere well wisher, Friend, and affectionate Queen.[17]

The pocketbook was an exquisite example of Charlotte’s own artistic endeavors, and of the economy of material exchange in which she operated.[18] On 16 December, following the delivery of the gift, the duchess of Portland wrote a reply to the lady-in-waiting Mary Hamilton on behalf of Delany, whose eyesight, at the age of eighty-one, was beginning to fail:

Mrs Delany attempted to write to you to express her gratefull [sic] acknowledgements to the Queen, for the magnificent present Her Majesty did her the Honour to bestow on her; but is miserable to find her Eyes fail her too much to gratifye [sic] her sensibility on this occasion; indeed I think nothing can exceed her gratitude, she was delighted! with the Elegance & taste of the pocket-book & its contents; but when I read the Letter to her (her Eyes being too weak to read it herself) she was quite overcome, to receive such a mark of high Honour & great Condescension of her Majesty; which she shall ever esteem as a Treasure of the greatest value.[19]

The rapidly diminishing quality of Delany’s eyesight was well-known amongst her circle by the winter of 1781. In November, Mrs. Boscawen wrote to Delany, “if eyes were to be purchas’d, what presents you wou’d receive!” In the same letter, Boscawen reveals the difficulty Delany had in writing and reading her correspondence:

We certainly do love to see your handwriting…if it has cost you the least degree of pain, Spin on therefore, my dear madam, and remember me sometimes while you turn your wheel, but don’t tell me so (in writing).[20]

As Boscawen reveals, for Delany and those in her social milieu, handicraft could function as an alternative form of communicating emotional attachment and recalling absent friends. For Delany in particular, it served as another medium in which to invest her voice as writing became more and more challenging. The pocketbook worked in much the same way, revealing the broad encompassing of craft as an emotional and social language. Serving as an extension of her physical self, its intended function was to evoke memory of the bodily-absent queen in moments “when no dearer Person’s are present,” suggesting an imagined proximity between creator and recipient, one realized in the materials of the craft and emphasized by Charlotte’s request that Delany “wear” it.[21]

The methods and experience of producing both paper-cuts and embroidery had much in common, sharing materials, tools, and techniques. Often, scissors and knives used in needlework would be similarly employed to cut and slice delicate cut-paper designs and would be associated with works produced in each medium. This conversational overlap of both materials and methodology in the two disciplines is clearly represented in the tools gifted by Charlotte and contained within the pocketbook. Certainly, Charlotte was familiar with Delany’s working methods and, at Bulstrode, had direct access to the spaces in which she worked and the tools with which she undertook that work. In a letter to her niece Mary Port, written in the autumn of 1782, Delany records how the queen was a regular witness to her craft:

On Saturday, as I was at my usual work, and the Dss D. of Portland just preparing for her breakfast, between 11 and 12, her Majesty, Princess Royal, Princess Mary, and Princess Sophia, attended by Lady Courtown, walk’d into the drawing rooms, and caught me…in some confusion, which was soon dispers’d by the Queen’s most gracious (I may say) kind manner. She would not suffer me to remove any of my litter, but said it was her wish to see me at my work; and by her command I sat down and shewed her my manner of working, which her great politeness made her pleased with.[22]

It is generally agreed that Delany rarely, if ever, used graphite to sketch her patterns prior to cutting the paper. Rather, it was done by eye. If she cut from life in front of her, then the album gifted to Charlotte can be viewed as an intimate record of interactions between the two. A silhouette of George III at the start of the album points to an intimate acquaintance with and regular proximity to the king. Appearing as a sort of pasted-in frontispiece, it sets the tone of the work and, possibly, serves as a visual dedication to the monarch. This would also suggest, then, that the album was created as a gift and that Charlotte was, most likely, the intended recipient from its earliest inception.

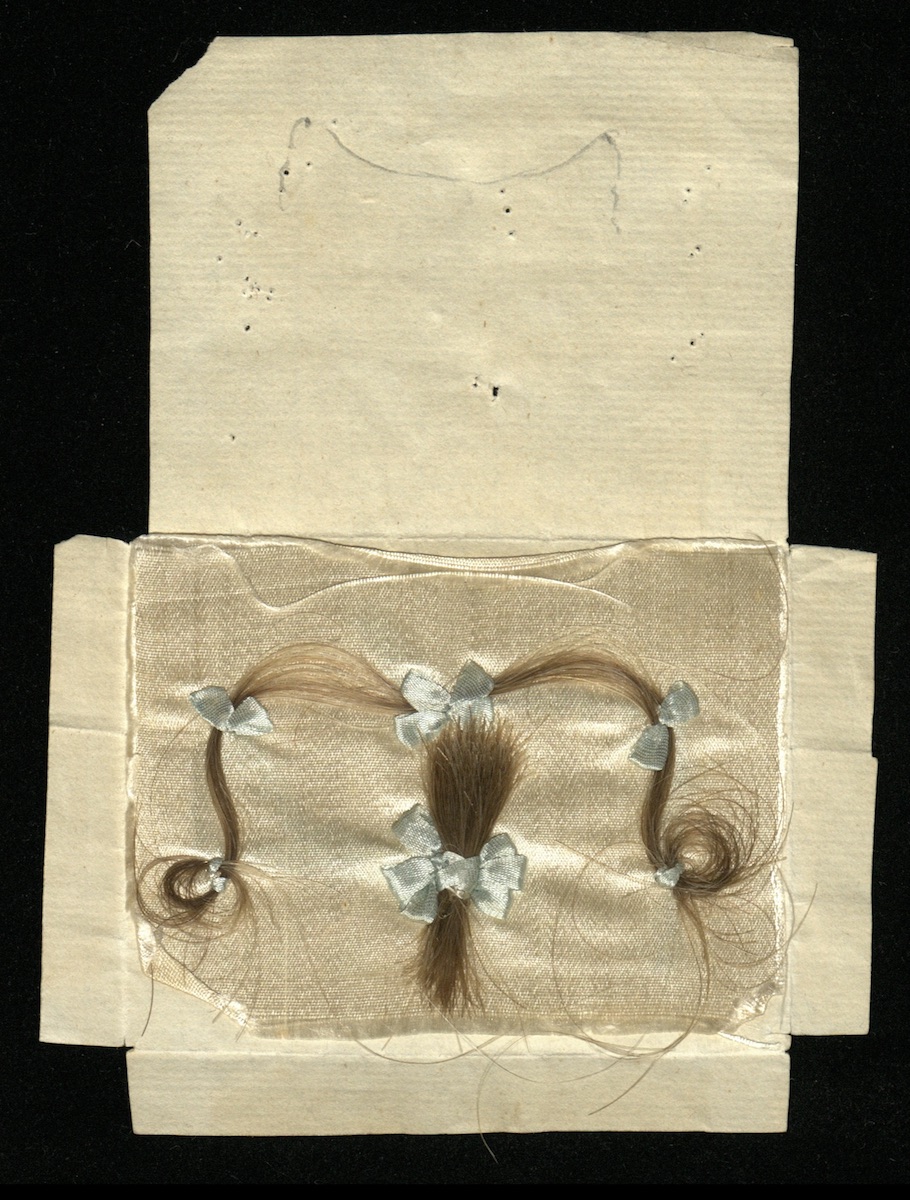

Fig. 4. Lock of Queen Charlotte’s hair mounted on silk and tied with blue ribbon by Mary Delany, 1781. GEO/ADD/2/64. Image: The Royal Archives, Windsor / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018.

The material expressions of friendship shared between Queen Charlotte and Mary Delany were valued for the physical and intellectual labours of crafting by which they came to exist, as much as by their qualities as finished and gifted items. Composite and collagic in their designs, work done by each woman drew on the productions of the other. Poignantly, a lock of the queen’s hair (Fig. 4), gifted to Delany in 1780 mounted on silk (possibly weaved by Delany) encased in a paper packet, also survives at the Royal Archives. The hair is fastened with blue ribbon, tied in bows –the same blue ribbon, also tied in bows is used on the spine and boards of Delany’s album, created a few short months later, confirm the development of a distinctive aesthetic language that united many of the objects made and shared within their friendship, and positioning the album itself at the heart of such collaboration and exchange.

Madeleine Pelling is a PhD candidate in History of Art at University of York, UK

Acknowledgements: Research for this essay was conducted during my fellowship with the Royal Archives and King’s College London as part of the Georgian Papers Programme in 2017. I am particularly grateful to Professor Arthur Burns for offering me the opportunity to contribute to this exciting research project and to Dr. Oliver Walton, Dr. Roberta Guibilini, Dr. Carly Collier and all the staff of the Royal Archives and Royal Library for their support and suggestions during my time in the archives. I am also grateful to Dr. Joanna Marschner, Senior Curator at Historic Royal Palaces, for providing me with unparalleled access to the Enlightened Princesses exhibition at Kensington Palace, and for her helpful insights in thinking about Queen Charlotte and the creative life of the Georgian court. This research was presented in April 2018 at the “Collage, Montage, Assemblage: Collected and Composite Forms, 1700-Present” conference at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, University of Edinburgh. I am especially grateful to Dr. Freya Gowrley and Dr. Cole Collins for their invitation to present my work, and to the audience for their generous suggestions.

[1] Ruth Hayden, Mrs. Delany and Her Flower Collages (London: British Museum Press, 1992), 166.

[2] Mark Laird and Alicia Weisberg-Roberts eds., Mrs. Delany & Her Circle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

[3] For more on the duchess of Portland and her museum, see Beth Fowkes Tobin, The Duchess’s Shells: Natural History Collecting in the Age of Cook’s Voyages (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014); Stacey Sloboda, “Displaying Materials: Porcelain and Natural History in the Duchess of Portland’s Museum,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, 43: 4 (Summer 2010), 455-472; Madeleine Pelling, “Collecting the World: Female Friendship and Domestic Craft at Bulstrode Park,” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 41: 1 (2018), 101-120.

[4] The duchess of Portland to Mary Dewes, May 1768. Llandover, ed., The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany, 6 vols. (London: Bentley, 1861-2), IV, 146.

[5] Delany, 5 July 1779, Autobiography and Correspondence, V, 444.

[6] Delany, Letters from Mrs. Delany to Mrs. Frances Hamilton, from the year 1779, to the year 1788: comprising many unpublished and interesting anecdotes of their late majesties and the Royal Family (London: Longman & Co., 1820).

[7] Clarissa Campbell-Orr, “Queen Charlotte, ‘Scientific Queen,’” in Queenship in Britain, 1660-1837: Royal Patronage, Court Culture and Dynastic Politics, ed. Clarissa Campbell-Orr (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 236-266, 240.

[8] Hayden, Mrs. Delany and her flower collages, 166.

[9] Clarissa Campbell-Orr, “Mrs. Delany and the Court” in Mrs. Delany & Her Circle, 61.

[10] Ibid, 113.

[11] Johanna Ilmakunnas, “Embroidering Women and Turning Men: Handiwork, Gender, and Emotions in Sweden and Finland, c. 1720–1820,” Scandinavian Journal of History 41, 3 (2016), 314.

[12] Princess Elizabeth to Prince Augustus, 6 February 1791. GEO/ADD/11. The Royal Archives, Windsor.

[13] Delany, Book of découpage, RA/GEO/ADD/2/65. The Royal Archives, Windsor.

[14] Delany to Miss Port, 18 November 1781, Autobiography and Correspondence, III, 69.

[15] Hamilton to Delany, 14 November 1781, Autobiography and Correspondence, III, 66. Italicisation as in Llandover’s text.

[16] The set was described in a note written by Delany’s waiting woman, see Hayden, Mrs. Delany and Her Flower Collages, 155.

[17] Queen Charlotte to Mary Delany, 15 December 1781. GEO/ADD/2/68. The Royal Archives, Windsor.

[18] The pocketbook has become an object of increasing interest to scholars of material culture and the royal court see the exhibition catalogue by Joanna Marschner, David Bindman and Lisa L. Ford eds., Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the Shaping of the Modern World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017).

[19] Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, duchess of Portland to Mary Hamilton, 16 December 1781. Mary Hamilton Papers, HAM/1/7/11/2, University of Manchester Library.

[20] Mrs. Boscawen to Mary Delany, 12 November 1781, Autobiography and Correspondence, III, 64-65.

[21] For more on the pocket as a private and gendered space in the eighteenth century, see Ariane Fennetaux, “Women’s Pockets and the Construction of Privacy in the Long Eighteenth Century,” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 20:3, (Spring 2008), 307-334.

[22] Delany to Mary Port, 22 October 1782, Autobiography and Correspondence, III, 58.

Cite this article as: Madeleine Pelling, “Crafting Friendship: Mary Delany’s Album and Queen Charlotte’s Pocketbook,” Journal18 (October 2018), https://www.journal18.org/2909.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.