Robert Wellington

What spectacle offers he to our eyes?

Is le Cercle alive? It looks like it breathes.

Benoist, your ingenious art

By a novel secret seems to animate the wax.

I admire your rare talent;

Your portraits, of an excellent taste,

Cause extreme surprise

One seems to see the persons themselves,

And never was anything made more lifelike.[1]

Of the many thousands of likenesses of Louis XIV made during the Sun King’s long reign, Antoine Benoist’s startling wax bust is the most unsettling (Fig. 1).[2] A lone survival of the artist’s wax œuvre, this relief of the monarch past his prime is one of many such portraits that Benoist made of kings, queens, courtiers, and foreign ambassadors. In his Left Bank Paris home, Benoist created one of the first galleries of waxworks that opened more than a century before that of the famous Madame Tussaud. Benoist’s waxworks were a popular attraction and visitors from all over the world came to see his work. When the Moroccan ambassador, Abdallah ben Aïscha, was taken to see them in 1699, he declared, “if following the Law of Mohammed, portraiture is a crime, those made in wax are an abomination, & M. Benoist will be more damned than all other painters.”[3] The envoy of the Bey of Tripoli agreed. Of the four planes of hell, Benoist belongs in the lowest, he averred, as “his art so closely approaches the work of God.”[4] Reports such as these of shock, wonder and admiration for Benoist’s lifelike portraits—so real that they competed with the work of the Creator—abound in sources from the time. He received enduring royal patronage and was awarded the title of premier sculpteur en cire coloriée. Yet it is difficult to understand today how such gruesome fidelity could please Louis XIV and win his approbation.

Fig. 1. Antoine Benoist, Louis XIV, c. 1705. Relief in white beeswax, painted, glass enamel eye, human hair, white lace, silk, cramoisy velvet, pins and nails, 52 × 42 cm. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)/Gérard Blot.

This short essay seeks to place Benoist’s wax relief within the broader contexts of the artist’s oeuvre and representations of Louis XIV more generally. Contemporary accounts of Benoist’s lost gallery of waxworks reveal strategies of display strikingly similar to those deployed by Charles Le Brun in his grands décors at Versailles. In the rue des Saints-Pères in Paris’s Saint-Germain neighborhood, Benoist staged a spectacle of courtly magnificence, with foreign visitors to France appearing as waxwork spectators to the Sun King’s court, attesting to his place at the center of local and global power. Here I contend that Benoist’s lifelike wax portraits of Louis XIV can be understood as part of the comprehensive strategy to represent the king’s gloire.

Benoist’s high-relief wax bust of Louis XIV (c. 1705) is one of eleven paintings and wax portraits of the king that the artist made from life during his career.[5] Verisimilitude can be found in the modelling of the king’s face, but also in the figure’s clothing and accessories. The king wears a perruque, which recent conservation work (Fig. 2) revealed to be made of human hair, once brown, but now faded to grey. He is dressed in a lace-trimmed chemise, wearing a cramoisy velvet jacket and the cordon bleu, the blue ribbon sash that held the cross of the Order of Saint-Esprit. The eyes are painted enamel and the flesh is rendered in beeswax painted in the sallow tones of the king’s skin, highlighting ephemeral details as well as imperfections accrued by a lifetime of wear: stubble, wrinkles, and small pox scars. With their seemingly random distribution and form, these blemishes are so convincing that some have speculated the portrait was made from casts of the king’s actual face.[6] Little is known about the artist’s process, but by the time this profile was made, he had perfected his craft over four decades. Benoist’s unyielding verisimilitude contravenes the rules of good taste laid out by Charles-Alphonse du Fresnoy in his influential poem The Art of Painting (De arte graphica), where he suggested that the artist should elide or improve upon natural defects.[7] Such judgements might help explain why Benoist was received into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture relatively late in his career (in 1681) for his fine painted portraits and not his wax sculptures.

Fig. 2. Video of the Restoration of the Wax Portrait of Louis XIV. From the Château de Versailles on YouTube.com (https://www.youtube.com/user/chateauversailles)

Benoist obtained the right to make and exhibit a series of wax portraits of Le Cercle Royal (or Le Cercle for short) in 1668. The attraction, open to the public for a small fee and recommended by popular tourist guides of the day, made him so famous that he was called Benoist du Cercle.[8] Unlike the extant wax relief, the figures displayed in Le Cercle were sculpted in the round, dressed in real clothes so that they appeared full length and life size. A room sheet given to those who visited Le Cercle listed the names of those represented according to their distribution in the room. Naturally, the king, queen, and dauphin appeared in the middle of the gallery surrounded by court nobles. More surprising is the inclusion of unnamed figures from elsewhere: A lady of Poland [Une Poulonoise], A Russian gentleman [Un Moscovite], and the Turkish Ambassador, Suleiman Aga, who also orbited around the royal family.[9] In the years that followed Benoist would continue to add to this cosmopolitan troupe, with a growing display of exotic envoys who came to pay homage to Le Cercle Royal.[10]

By 1687, visitors from distant lands made up a large part of Benoist’s display in the rue des Saints-Pères, as Germain Brice’s description reveals:

All the Ambassadors from the furthest nations who have come to France in the last ten years, are also represented there with great fidelity in the clothes that they wore for their first audience, & which have for the most part been donated by them to appear in the Cercle. The Doge of Genoa & the four Senators from the same republic who accompanied him. The King & Queen of Spain, The King of England, & others: All of these latter figures are placed in manner of a Balcony, from where they seem to look upon the Cercle of France…[11]

Le Cercle was as much an exhibition of costume as it was of portraits. It recreated the spectacle of exoticism that characterized ambassadorial court entries, where French courtiers clamored to see the habits, manners, and physiognomies of foreign visitors.[12] If it seems unlikely that Benoist managed to divest these stately guests of their valuable court attire, it must be remembered that he was a man of exceptional privilege. He held the office of valet du chambre to the king, for whom he was listed as peintre ordinaire in the royal ledgers since 1657.[13] He had regular access to the royal household, and such was his fame that James II called him to London to record his likeness in wax.[14]

What must have appealed to visitors of Le Cercle was the opportunity to look long and hard at the faces and costumes of those whom they might otherwise only see at a glance or from afar. In the case of foreign envoys, the opportunity to glimpse them firsthand was especially fleeting. The wax relief of Louis XIV supports accounts of Benoist’s mastery of verisimilitude, and of his ability to persuade viewers that “they see the person themselves,” to quote again from Baraton’s madrigal.[15] We might compare the artist’s display of virtuosic illusionism to similar strategies employed by Charles Le Brun at Versailles, most notably in Le Brun’s attempt to portray a perpetual audience of foreign visitors to the court of Louis XIV in the Escalier des Ambassadeurs.

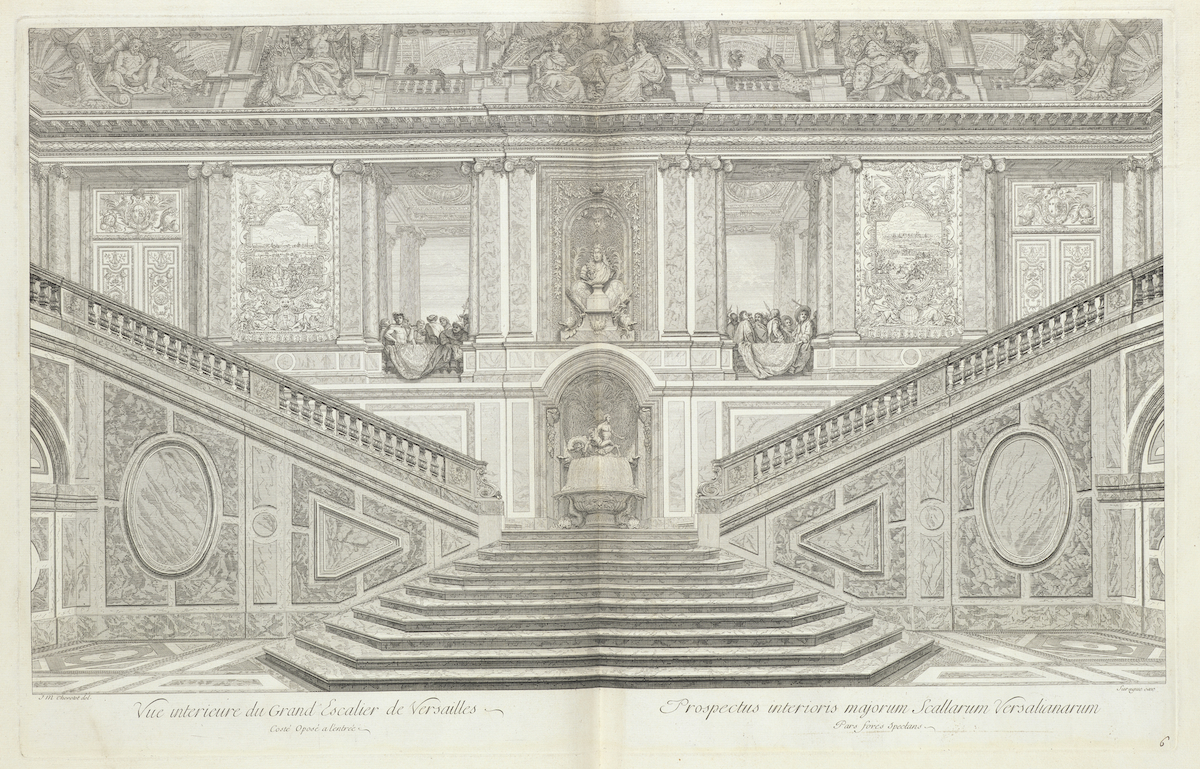

Brice’s description of Le Cercle, where foreign envoys and princes gaze down upon the king and his household from a balcony, strongly recalls the figures from the four corners of the world that appear in fictive balconies painted by Le Brun at Versailles (Fig. 3), a design that predates Brice’s description of Le Cercle by a decade. Appearing on either side of the main staircase on the first floor, and mirroring the walls opposite them, Le Brun’s trompe l’oeil balconies, four in total, were each dedicated to a continent, and represented figures from Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas in national dress. In the words of Le Brun’s student and biographer Claude Nivelon, “one could say that when this great king and his court descend by that staircase… it would make a spectacle so grand and superb one could believe that all these people crowd here to honour his passage and to see the most beautiful court in the world.”[16] Likewise, Benoist’s display of waxworks performed the same act of international spectatorship that Nivelon recognized in Le Brun’s design, with the Sun King as the subject of a global gaze.

Fig. 3. Jean-Michel Chevotet and Louis Surugue (after Charles Le Brun), Vue interieur du grand escalier de Versailles costé oposé à l’entrée, 1725. Etching and engraving. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Early in his reign Louis XIV declared that his gloire was the thing most precious to him above all else.[17] The Sun King’s pursuit of princely gloire, a concept that captures notions of glory and reputation, might seem difficult to reconcile with Benoist’s gruesome likeness. Yet placing the wax relief portrait in the broader context of Benoist’s oeuvre casts new light on what might otherwise be regarded as an historical oddity. It reveals the role of lifelike wax figures in staging a permanent performance of the Sun King’s universal fame. Benoist’s waxworks enacted a three-dimensional spectacle of gloire that complemented Le Brun’s painted figures for the Escalier des Ambassadeurs, revealing a continuity in royal representation from the most revered grand decorations at Versailles to a popular public display in Paris. Le Cercle was, perhaps, the first commercial exhibition of wax celebrity portraits assembled long before those of Phillipe Curtius in the Palais Royal and Madame Tussaud in London in the late eighteenth century.[18] But unlike those more famous attractions, Le Cercle was a project sanctioned by royal decree, and as such must be understood within the wider program of royal representation created under the auspices of Louis XIV. The surviving wax relief, with its unflinching portrayal of the king’s features, provides just a hint of that uncanny spectacle of kingship once found at Le Cercle on the rue des Saints-Pères.

Robert Wellington is a Lecturer at the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University, Canberra

[1] Quel spectacle s’offre à nos yeux?/ Le Cercle est-il vivant? On dirait qu’il respire./ Benoist, ton art ingénieux/ Par un secret nouveau semble animer la cire./ J’admire ton rare talent;/ Tes portraits, d’un goût excellent,/ Causent une surprise extrême;/ On croit voir la personne même/ Et jamais on n’a fait rien de plus ressemblant. “A M. Benoist, Peintre ordinaire du Roy, & son premier Sculpteur en cire,” in Martin Baraton, Poesies diverses… Par M. Baraton (Paris: Jean-Baptiste Delespine, 1705), 281-282.

[2] The most comprehensive account of Antoine Benoist’s wax portraits is Adolphe Dutilleux, “Antoine Benoist, premier sculpteur en cire de Louis XIV (1632-1717),” Revue de l’histoire de Versailles et de Seine-et-Oise (1905), 81-97, 198-213. See also Milovan Stanić and Alexandre Maral, “Portraits en cire de Louis XIV,” in N. Milovanovic and A. Maral (eds.), Louis XIV: L’homme et le roi (Paris: Skira, 2009), 225-227.

[3] “Si suivant la Loy de Mahomet la portraiture estoit un crime, celuy de faire des portraits en cire estoit une abomination, & que M. Benoist seroit encore plus damné que tous les autres peintres.” Mercure galant (April, 1699), 62.

[4] “Son art approché de si près de l’oeuvre de Dieu…” Mercure galant (July, 1704), 143-45.

[5] This number is provided in the papers written in support of Benoist’s ennoblement. Lettres de relief de dérogeance à noblesse en faveur d’Antoine Benoist, 1706, transcribed in full in Anatole de Montaiglon and Jules Guiffrey, “Antoine Benoit, sculpteur en cire,” Nouvelles Archives de l’art français (1872), 303-306.

[6] Stanić and Maral, Louis XIV: L’homme et le roi, 226.

[7] Charles-Alphonse du Fresnoy, L’Art de Peinture (Paris: Nicolas l’Anglois, 1668).

[8] Stanić and Maral, Louis XIV: L’homme et le roi , 225.

[9] The room sheet is transcribed in Dutilleux, “Antoine Benoist,” 85.

[10] Benoist’s privilege was extended in 1688, formally allowing him to “make in wax and exhibit in public the ambassadors of Siam, Morocco, Moscow, Algeria, The doge of Genoa and others.” Privilège pour faire en cire et exposer en public les ambassadeurs de Siam, Maroc, Moscovie, Alger, doge de Gênes et autres, etc., 1688, transcribed in A. B., “Variétés: la cérographie et les figures de cire sous Louis XIV,” Annuaire-Bulletin de la société de l’histoire de France 11 (1874), 168–170.

[11] “Tous les Ambassadeurs des Nations les plus éloignées qui sont venus en France depuis dix ans, y sont aussi tres-fidellement representez, dans les habits qu’ils avoient le jour de leur premiere audience, & qu’ils ont plûpart donnez pour paroître au Cercle. Le Doge de Genes & les quatre Senateurs de la mesme Republique qui l’accompagnerent. Le Roi & Reine d’Espagne, Le Roi d’Angleterre & quelques autres: Tous ces derniers figures sont placés dans une manière de Balcon, d’où il semble qu’elles regardent le Cercle de France…” Germain Brice, Description nouvelle de ce qu’il y a de plus remarquable dans la ville de Paris, 2nd ed. (Paris: Jean Pohier, 1687), 2:221.

[12] See, for example, accounts of the visit of ambassadors of Phra Narai, King of Siam, to Versailles in 1686. Ronald S. Love, “Rituals of majesty: France, Siam, and royal image-building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686,” Canadian Journal of History 31:2 (August 1996), 171–198; and Meredith Martin, “Mirror Reflections: Louis XIV, Phra Narai, and the Material Culture of Kingship,” Art History 38:4 (2015), 653–667.

[13] Dutilleux, “Antoine Benoist,” 82.

[14] Dutilleux, “Antoine Benoist,” 91-92.

[15] See note 1.

[16] “on peut dire que lorsque ce grand roi descend par cet escalier, au milieu et suivi de tous les princes et princesses, cela fait un spectacle si grand et superbe que l’on croirait que tous ces peuples se rendent en foule dans ce lieu pour honorer son passage et voir la plus belle cour du monde.” Claude Nivelon III, Vie de Charles Le Brun et Description Détaillée de ses Ouvrages: Édition critique et introduction par Lorenzo Pericolo (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 2004), 472.

[17] On Louis XIV and gloire see Robert Wellington, Antiquarianism and the Visual Histories of Louis XIV: Artifacts for a Future Past (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 41–42.

[18] See Vanessa Schwartz, Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999), 92 ff.

Cite this note as: Robert Wellington, “Antoine Benoist’s Wax Portraits of Louis XIV,” Journal18, Issue 3 Lifelike (Spring 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1421. DOI: 10.30610/3.2017.6

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.