#20 Clean (Fall 2025)

ARTICLES

Economies of Waste: Revolutionary Administration and the Afterlives of the Kings of Notre-Dame

Demetra Vogiatzaki

“Beneath the Waters of a Universal Ocean:” Containing, Contaminating, and Cleaning the Ganges River in Varanasi

Ushma Thakrar

Piss, Poison, and other Paths between Scotland and England in Caricature since 1745

Laura Golobish

CONVERSATION PIECE

The Grammar of Cleaning: A Conversation

Maarten Delbeke, Noémie Etienne, and Nikos Magouliotis

Issue Editors

Maarten Delbeke, ETH Zurich

Noémie Etienne, University of Vienna

Nikos Magouliotis, ETH Zurich

Cleaning is never a neutral act. In the eighteenth century, acts of cleaning became a way to decide what counted as disorder, to separate asserted purity from designated pollution, and to display authority over matter, space, and people. From the forecourt of Paris’s Notre-Dame to the Ganges river in Varanasi to Scotland’s filthy privies, practices of cleaning have shaped political order. Racial issues, colonization, and the management of public space revolved around the idea and implementation of cleaning, which could also involve the deliberate relocation or erasure of human beings.

In this issue, Demetra Vogiatzaki focuses on Revolutionary Paris, where cleaning often meant intentional architectural erasure. In 1796, the rubble of the decapitated kings of Notre-Dame was removed at night by a minor architect-bureaucrat. The once-cherished relics of monarchy were now treated as waste. In this case cleaning blurred the line between iconoclasm and sanitation, showing how revolutionary ideals were often realized through mundane acts of clearance.

As Ushma Thakrar shows, water in Varanasi was not just a resource; it was a medium through which political power was exercised. The Mughals, the Marathas, and later the British successively redefined what it meant to clean the river by building channels and ghats for ritual purification, or by draining tanks as stagnant nuisances. In each case, cleaning the waterscape meant more than just maintenance: it reshaped authority over the sacred city.

Laura Golobish highlights how filth became a metaphor in British satirical prints. The Scots were repeatedly depicted as dirty and contagious. Scenes of overflowing privies or unkempt laundresses were not neutral observations on hygiene. Instead, they were ways of marking cultural difference which was often a sign of political anxiety: to portray Scotland as unclean was to reinforce an English vision of order and national identity.

Finally, the conversation among Noémie Étienne, Maarten Delbeke, and Nikos Magouliotis extends these insights through various other instances of cleaning as a political act. After the French Revolution, the cleaning of soot-darkened church paintings symbolized not only technical preservation but also their secular reclassification as national heritage. Delbeke, meanwhile, turns to architecture, where calls for purification took on metaphorical force. Bavarian Elector Maximilian II Joseph’s 1770 decree against rococo stucco-work presented “ornament” as excess to be cleaned away. Whitewashing and the removal of historical ornaments embodied political and religious struggles, recasting style as an index of moral and civic order.

If cleaning means writing a history of control, it paradoxically also allows us to write an (art) history from below. Thus, we ask: Who actually did the dirty work? Étienne’s archival research highlights the prominent, albeit rarely visible, role played by women, children, and other marginalized people who actually did the job of cleaning. This gendered dimension resonates with Golobish’s study of laundresses and chambermaids and their depiction in British prints.

Read together, these cases reveal a grammar of cleanliness across the eighteenth century. Dirt could be stagnant water, bodily filth, architectural rubble, or ornamental excess. Cleaning could take the form of drainage, whitewashing, or caricature. Yet in every instance, it redrew boundaries between religious and secular, purity and corruption, inclusion and exclusion.

Furthermore, cleaning rarely meant complete erasure, but rather displacement or transformation. The decapitated kings of Notre-Dame disappeared from the forecourt but remained as an absence, a rupture in memory. The drained tanks of Varanasi left behind recollections of sacred catchments. Satirical caricatures smeared Scotland with filth, but their endless repetition betrayed persistent unease. Thus, to study cleanliness in the eighteenth century is to study control, power, and management. The contributions by Vogiatzaki, Thakrar, and Golobish, as well as the conversation among the issue editors, invite us to consider who defined dirt, who performed its removal, and whose vision of the world it served. Moreover, as previously suggested, acts of cleaning and erasure can sometimes provoke resistance in objects, memories, and people, even if only on the margins. These traces and fragments now hint at the history of what has been removed, and that which, at first glance, no longer exists.

Maarten Delbeke, Noémie Etienne, and Nikos Magouliotis

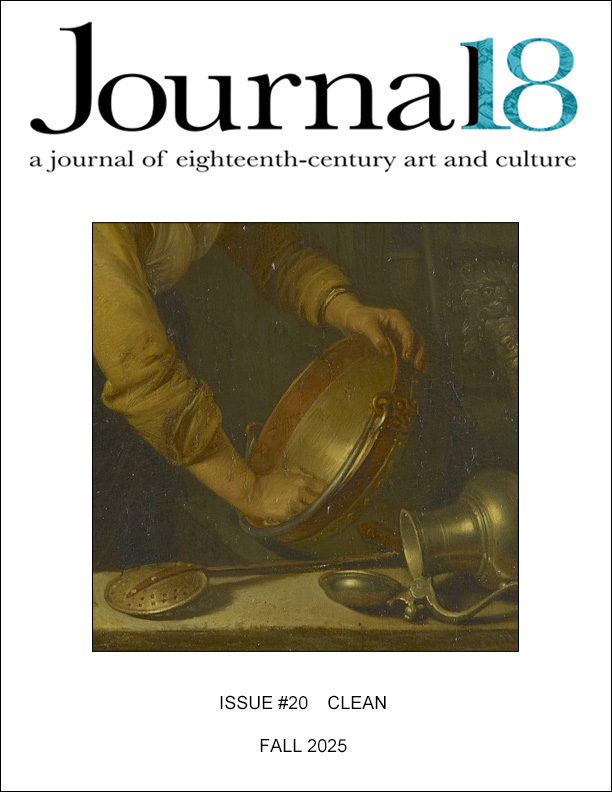

Cover image: Gerrit Dou, A Maidservant Scouring a Brass Pan at a Window, 1663. Oil on panel, 16.6 x 13.1 cm. RCIN 404618. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust.