Fig. 1. Beyoncé performing during The Formation World Tour at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California on May 16, 2016. Photo © Kevin Edwards https://www.flickr.com/photos/keved/26805014910/

In April this year, HBO debuted the film accompanying Beyoncé’s sixth album, Lemonade. The film and the album’s twelve tracks were released on Tidal and iTunes a few days later. Viewers immediately asked if the album’s exploration of infidelity attested to longstanding rumors about Beyoncé’s husband, Jay-Z. But they also noted the album’s emphasis on the experiences of black womanhood and its critique of police brutality, an issue of vital concern today.

“Freedom,” the antepenultimate track featuring Kendrick Lamar, situates Beyoncé’s bellowing call to liberty against an asphyxiating landscape of racism delineated by Lamar’s creaky, breathy voice. It ends in two parts: first, with Lamar asking, “Is it truth you seek? Oh father can you hear me? Hear me out;” then, with an excerpt from a speech by Hattie White (Jay Z’s grandmother): “I was served lemons, but I made lemonade.” If Lamar’s plea, likely unheeded, underscores the precarious terrain within which Beyoncé’s thunderous call to freedom struggles to materialize, then Hattie White’s words of survival offer a glimpse of resolution. In the track’s translation for the visual album, the sounds of the night accompany the camera as it glides over the heads of a small crowd of black women, including mothers of victims of police brutality, who have gathered in front of an outdoor stage. The sounds are silenced as Beyoncé sings the first lines of the song acapella. At this moment, the camera slowly turns away from the crowd, faces the singer and begins to approach her on the stage. The chorus and instruments join her voice suddenly as she begins to sing the main refrain, “Freedom, Freedom, I can’t move! Freedom, Freedom, Cut me loose!”

This moment of pure voice in “Freedom,” as Beyoncé sings the first verse of the song acapella, and its pairing with the visualization of the album’s title in the film illuminate an alternative conceptualization of freedom that emerged in the late eighteenth century and challenged the Enlightenment’s accommodation of slavery. My aim in this essay is not to proffer an Enlightenment source, however radical, for Beyoncé’s album. Indeed, as I hope to show, this alternative Enlightenment discourse was rarely visualized within eighteenth-century art and visual culture in Europe. Instead, it is with the aid of a transhistorical imagination, one that looks from Beyoncé to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, that historians can begin to see through the blindspots created by and within Enlightenment discourse.

For example, Enlightenment thinkers primarily critiqued slavery as the failure of human sympathy, rarely addressing the humanity of the enslaved body. By placing emancipation within the purview of a reformed white sensibility (that is, at the behest of white Europeans to enslaved Africans), they deployed liberty and freedom as racialized terms.[1] The imagination of freedom within Enlightenment thought could thus remain untroubled by the empirical reality of the black body and even rely upon this reality’s erasure within much of the period’s art and visual culture. However, another model of freedom emerged in the late eighteenth century that disavowed these distinctions by foregrounding language as a dynamic, social condition of embodiment, thus defining itself as the work of coordination within and between bodies. Within this model, freedom could not be cognitive or social without also being corporeal. To recover this model in conversation with Lemonade is thus to trace an intellectual genealogy of freedom from the Enlightenment to the present; that is, to be emboldened by its universalist scope but not to deny its historical and material conditions.

The association of language and liberty famously guides Rousseau’s The Social Contract (1762) and is more thoroughly elaborated in his “Essay on the Origin of Languages” (1781), where he observes:

There are some tongues favorable to liberty. They are the sonorous, prosodic, harmonious tongues in which discourse can be understood from a great distance … but I say that any tongue with which one cannot make oneself understood to the people assembled is a slavish tongue.[2]

As Rousseau explains elsewhere in the essay, voice, as an outcome of the material fact of the body, accurately registers the movements of the soul.[3] He thus distinguishes its resultant authenticity from the corruption of language as convention. Voice as primal embodiment is also not subject to misunderstanding, and can thus be the perfect interface between one who speaks and one who listens. In Rousseau’s framework, discourse (that is, meaning) is most efficacious, indeed most reliable, as the product of embodied sense, so far as sense points to immanence.[4] Perceived through the lens of Rousseau, the acapella introduction of “Freedom” in Lemonade may appear as Beyoncé’s moment of pure voice, her earnest plea and empowering call to her audience. Indeed, as the camera lingers over her trembling, open mouth, we can imagine “Freedom” as the declaration of an autonomous and authentic subject.

But authenticity is not for consideration in an album that moves on parallel tracks of meaning, or what Zandria Robinson, drawing on Darlene Clark Hine, discusses as its “culture of dissemblance.” For example, the song “Sorry” (the expression is quickly followed by “I’m not sorry”) can be as much about Jay-Z’s purported infidelity as about Serena Williams masterfully flaunting her much-taunted physicality in response to the apology that she was notoriously denied following her harassment by spectators at Indian Wells. “Freedom” does not break from the album’s playful yet caustic making of double-meaning in order to register the kind of pure voice we encounter in Rousseau. Instead the stark, monochromatic setting of the acapella verse stands in marked contrast to the visualization of both the album’s title and its last track, “Formation.” With the inclusion of Hattie White’s speech in the track, “Lemonade” is placed within the semantic field of “Freedom.” In the film, unlike in the album where it stands unequivocally for the endurance of the black body repeatedly subject to violence, “Lemonade” is subtly expressed as a placeholder for the bonds of friendship and sisterhood that black women – running across fields, brushing each other’s hair, gathering around a table – forge with each other, generation after generation, generation across generation. In so doing, “Freedom” is not unveiled as the prerogative of an authentic, autonomous subject but as the condition of a subjectivity predicated on myriad becomings.

Video of Beyoncé’s Sorry from the album Lemonade

In her astute and eloquent discussion of the queer, feminist and aesthetic politics of Lemonade, Zandria Robinson underscores the importance of “coordination” to “community organizing and resistance,” especially the critical participation of “blackness on the margins.” Indeed, it is this kind of coordinated, communal “formation” that she observes in the album’s eponymously titled last track. Note that “Formation” is placed at the end of the album, accompanying the film’s credits, thereby acknowledging the names of all those involved in its making.

But coordination is not only an act of reaching out to another. It is also the dynamic condition of the body that interlinks thought and action. Far from privileging the autonomous subject, Enlightenment thinkers such as Johann Herder identified coordination as the principal attribute of what it means for humans to be free. Like Rousseau, Herder also examines the origin of language (1772), but he traces a different aspect of embodiment in defining language as follows:

… the total arrangement of all human forces, the total economy of his sensuous and cognitive, of his cognitive and volitional nature, or rather: It is the unique positive power of thought which, associated with a particular organization of the body, is called reason in man as in the animal turns it into an artifactive skill; which in man is called freedom and turns in the animal into instinct.[5]

For Rousseau, voice instantiates presence and conventionalized language registers “corruption.” Conversely, Herder proposes that language embodies the human capacity to reason as a dynamic process. Reason is not the prerogative of a disembodied intellect but emerges instead from the coordination of thought and action. As Herder contends, reason is not a “separate and singly acting power but an orientation of all powers.”[6] To be free, in his formulation, is not a pre-ordained condition for humanity, but rather a dynamic process of coordinating one’s sensory and cognitive faculties with each other and with the world. Although Herder does not directly address slavery in his treatise, he offers a model of freedom that remains fundamentally incompatible with the structural violence that perpetuates it.

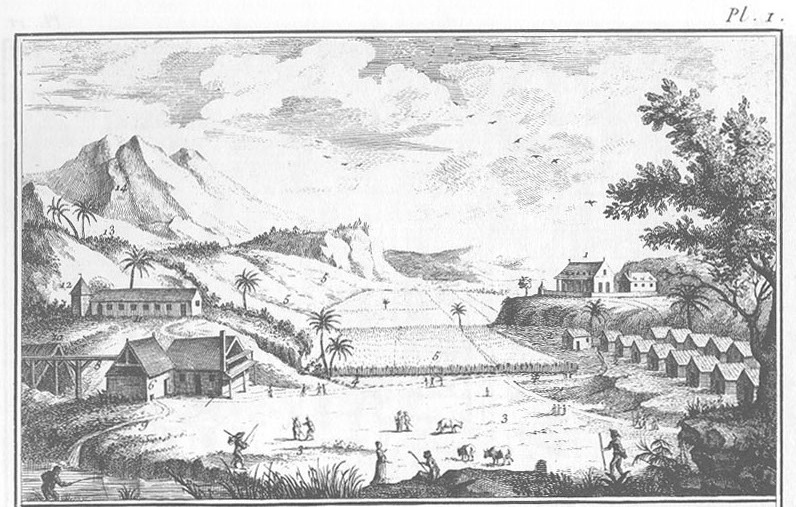

Fig. 2. Detail from “Plate I: Agriculture et économie rustique – Sucrerie et affinage des sucres,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates) (Paris, 1762). Image Source: The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.344 (accessed July 21, 2016).

Historians Sidney Mintz and Michel Rolph-Trouillot describe the process of “seasoning” undergone by slaves upon their arrival in the Caribbean as “new life patterns [that] had to be learned to fit new circumstances,” including new habits of eating, courting, dressing, defecating, and birthing.[7] Slaves thus underwent a drastic and traumatic process of resocialization under the constant threat of violence and death decried by slave-turned-citoyen Jean-Baptiste Belley:

This man brutalized by slavery, the whip always suspended over his head, brought back to childhood by horrible and cruel punishments that degrade humanity and modesty, this man is not without feeling… The development of an energetic thought would surely lead to the death of a slave who expressed it![8]

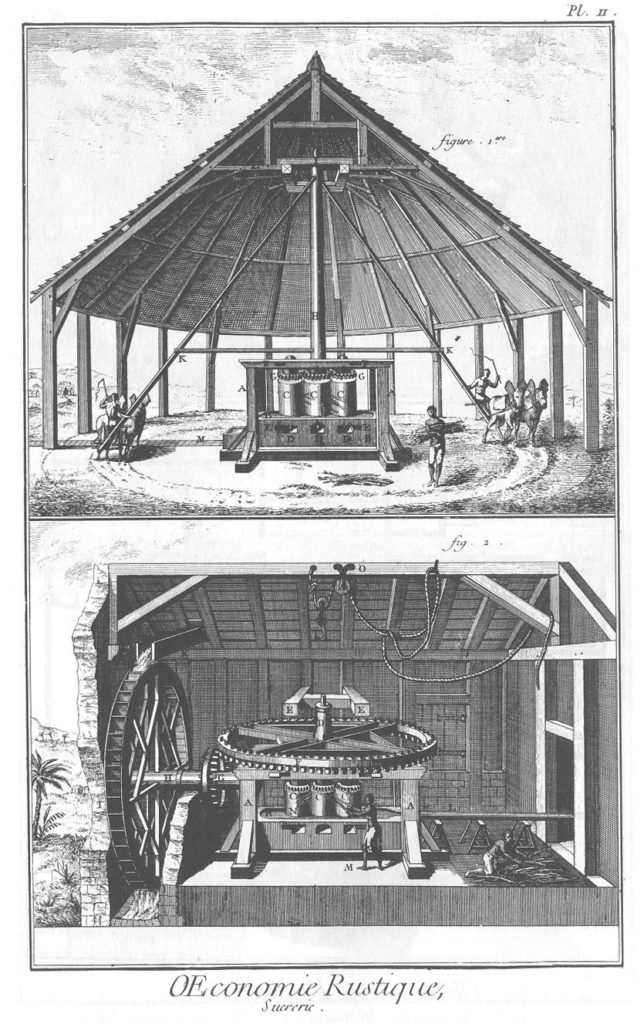

But the world of the plantation was depicted very differently in the art and visual culture of the Enlightenment.[9] For example, L’Encyclopédie included a “sucrerie” or sugar refinery among its plates, under the label “Oeconomie Rustique.” The plates (Figs. 2 and 3) depict the Caribbean plantation according to the conventions of picturesque landscape painting, wherein a harmonious concordance between nature and man is conveyed through the rubric of “agriculture,” which relies, as per this convention, not on coercively extracted human toil but rather on nature’s abundant gifts to the leisurely strolling bodies who dot its foreground and middleground. The orderly arrangement of the landscape allows the viewer to stroll through and consume the landscape as image, without any compositional or political disruption – that is, with no indication of the violence done to the enslaved body or the myriad slave rebellions that marked the plantation’s lifeworld. When Herder thus associates reason with freedom in his treatise, he does not merely offer a conceptual link between the two but rather highlights that they are predicated on a dynamic condition of lived experience, a condition not only systematically denied to the slave through the severing of action and thought but also one rendered invisible by the visual culture of the period. Moving fluidly back and forth between a plantation setting of indeterminate temporality and the present, the visual album for Lemonade underscores the continuing legacy and relevance of slavery to any conversation about the freedom of black bodies today. It also illuminates a strand of the Enlightenment discourse about freedom that demands to be seen in relation to the kind of black bodies that were largely neglected or erased in European art and visual culture.

Fig. 3. “Plate II: Agriculture et économie rustique – Sucrerie et affinage des sucres,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates) (Paris, 1762). Image Source: The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.344 (accessed July 21, 2016).

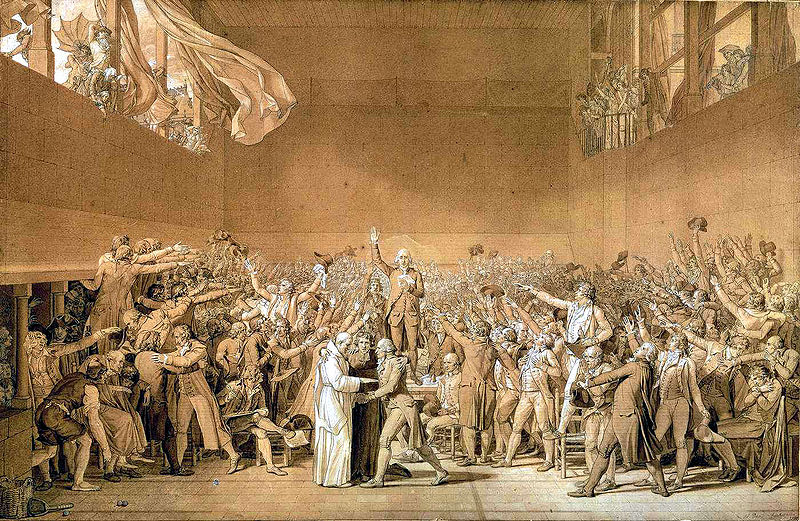

Allow me to end with a very different oath of the tennis court from the one with which we are more familiar, Jacques-Louis David’s The Oath of the Tennis Court (Fig. 4). On Saturday, July 9, with Beyoncé supporting her from the player’s box, Serena Williams won her 22nd Grand Slam title, equaling Steffi Graf for the highest number of titles won by a player on the WTA. Commentators spoke repeatedly of how Williams’s serve remains the strongest part of her game and illustrated their point with a slow-motion replay of one of her serves. In it, Williams nimbly tosses up a ball just as it glides off the edge of her fingers. As the ball takes flight, she leaps up and reaches out in front of her; her legs, arms, and torso are in formation as she moves in anticipation of the ball in mid-air, meeting it perfectly in the arc of its projection. As she serves an ace, Williams declares once again, with her body in formation (and ready to reach out to another), that she is free.

Fig. 4. Jacques-Louis David, The Oath of the Tennis Court, 1791. Graphite, pen, sepia wash heightened with white on paper, 65 x 105 cm. Musée national du Château, Versailles. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Zirwat Chowdhury will be an NEH Postdoctoral Fellow at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles in 2016/2017

[1] The term “liberty” is used more frequently in eighteenth-century discourse with regards to self-possession, but primarily with reference to property rights. “Freedom”, especially in the wake of Kant, instead refers to the cognitive ability to deploy one’s faculty of reason. But philosophical debates in the eighteenth century about the origins of language highlight some channels for putting these two terms into conversation.

[2] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Essay on the Origin of Languages which Treats of Melody and Musical Imitation,” in John Moran and Alexander Gode, ed. and trans., On the Origin of Language (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 72-73.

[3] For example, he explains that “[a]nger produces menacing cries articulated by the tongue and the palate. But the voice of tenderness is softer: its medium is the glottis.” Rousseau, “Essay on the Origin of Languages which Treats of Melody and Musical Imitation,” 50.

[4] My reading of Rousseau is largely informed by Jacques Derrida’s critique of presence in Gayatra Spivak, trans., Of Grammatology (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976).

[5] Johann Herder, “Essay on the Origin of Language,” in Moran and Gode, On the Origin of Language, 110.

[6] Herder, “Essay on the Origin of Language,” 112.

[7] Sidney Mintz and Michel Rolph-Trouillot, “The Social History of Haitian Vodou,” in Donald J. Cosentino, ed., Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou (Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Social History, 1995), 126.

[8] Jean-Baptiste Belley, “The True Colors of the Planers, or the System of the Hotel Massiac, Exposed by Gouli (1795),” in Laurent Dubois and John D. Garrigus ed., Slave Revolution in the Caribbean, 1789-1804 (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006), 145.

[9] Although one can also revisit Darcy Grigsby’s excellent discussion of Girodet’s singular portrait of Belley and consider if the sitter’s body is in “formation.” Darcy Grigsby, “Girodet’s Portrait of Citizen Belley, Ex-Representative of the Colonies, 1797,” in Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 9-64.

Cite this note as: Zirwat Chowdhury, “Lemonade‘s Enlightenment”, Journal18 (July 2016), https://www.journal18.org/735

Licence: CC BY-NC