Fig. 1. Chris Otley, Locust Ecdysis (after Robert Hooke), 2008. Graphite on paper, 84 x 119 cm. Photo: © Chris Otley.

While I have held a life-long fascination with natural history, the particular concerns and developing visual aesthetic of eighteenth-century anatomical illustration are central to my own artistic practice. From Robert Hooke, to William Cheselden, William Hunter, and George Stubbs, the clinical presentation of isolated specimens, drawn with unequivocal outlines while floating in the uncharted void of background space, claim to present an objective universal language of didactic scientific truth.[1] The obvious tensions at play between truth and ornament in scientific illustration throughout this period are themselves intriguing and inspiring. Yet it is primarily the fundamental negation of the conditions in which the artist presumably made their observations—the maggot-ridden horrors of Stubbs’ equine dissection barn, for instance—and instead, the offering of crisp, sharply-delineated outcomes, which drive my own selection of perfectly clean, off-white cartridge papers, combined with hard-edged meticulous use of graphite, as my preferred visual language (Fig. 1).[2] My drawings are often on a fairly large scale, but produced exclusively with a 0.5mm lead, allowing for a high level of control and fastidious detail.

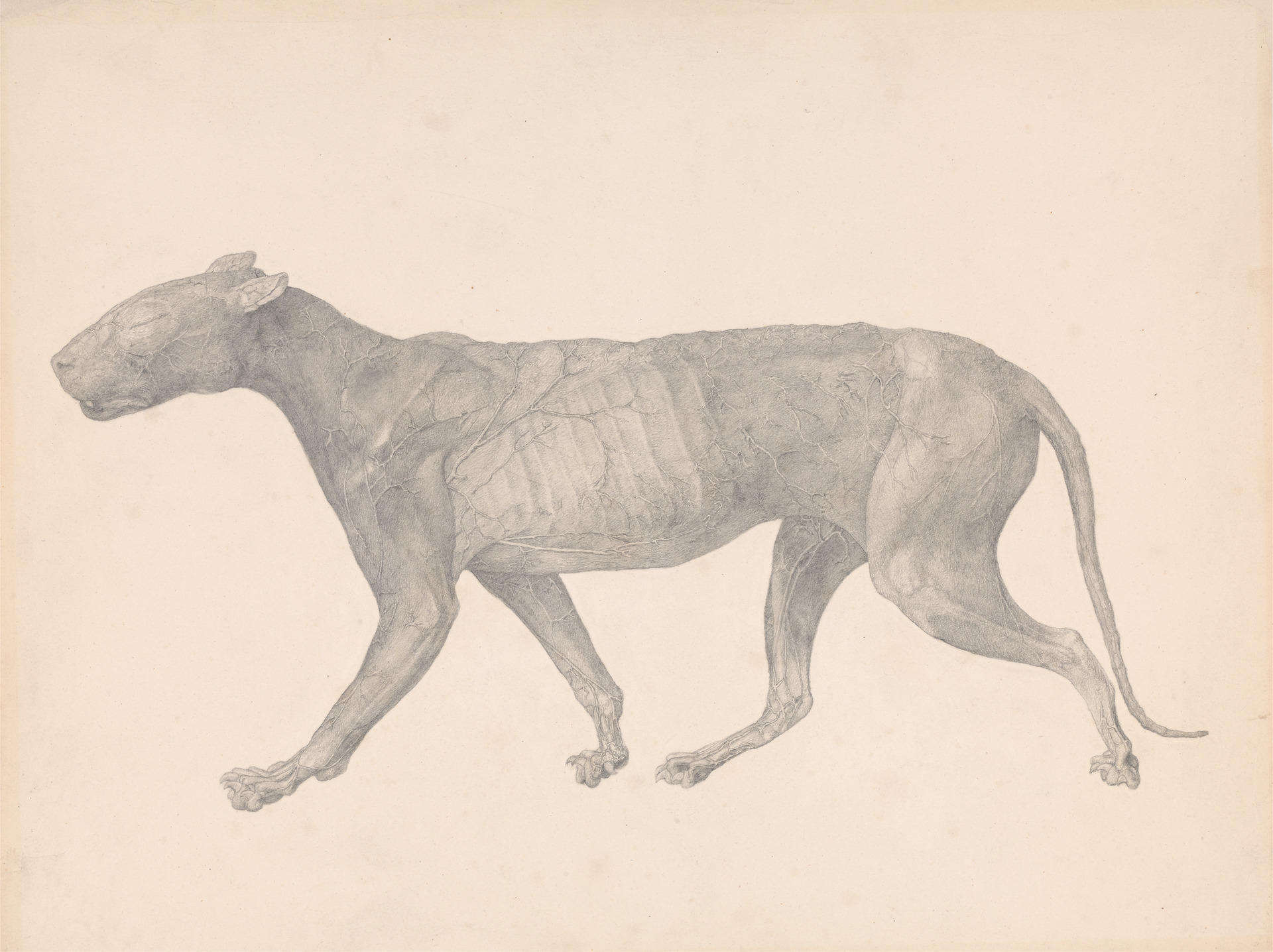

Fig. 2. George Stubbs, Tiger, Lateral View, with Skin and Tissue Removed (Finished Study for Table IX), between 1795 and 1806. Graphite on paper, 40.6 x 50.4 cm. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Image courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Stubbs’ specimens are rendered almost cartographically, recording with the pencil (and burin) the forms and structures encountered and navigated with the dissecting knife. The clarity, precision, and sensitivity employed in this process are encapsulated in his study of the near-intact body of a tiger (Fig. 2). The physical territory of the body is further clarified by the careful attention to the overall shape of its profile: there is an avoidance of overlap in the positioning of the legs, while a minute gap maintains the peninsula of the tail from being encroached upon by the arching back paw. Beyond this distinct coastline, the interior geography is explored with great delicacy. Delineating the subtlest of contours, Stubbs employs a broad tonality, ranging from the dark, shadowy spaces behind the tiger’s ears, to a complete absence of graphite, revealing the white surface of the paper, in the veins and arteries that spread and flow like tributaries across the body. The intricate network of veins seems relatively hard-edged in comparison with the effect of soft translucency given to the thin layer of skin stretching across the ridges and valleys of the ribcage. The viewer is not only able to circumnavigate the basic profile of the tiger, but also to survey its surface form and textures and almost to penetrate beneath the skin, such is the wealth of visual description in Stubbs’ mapping.

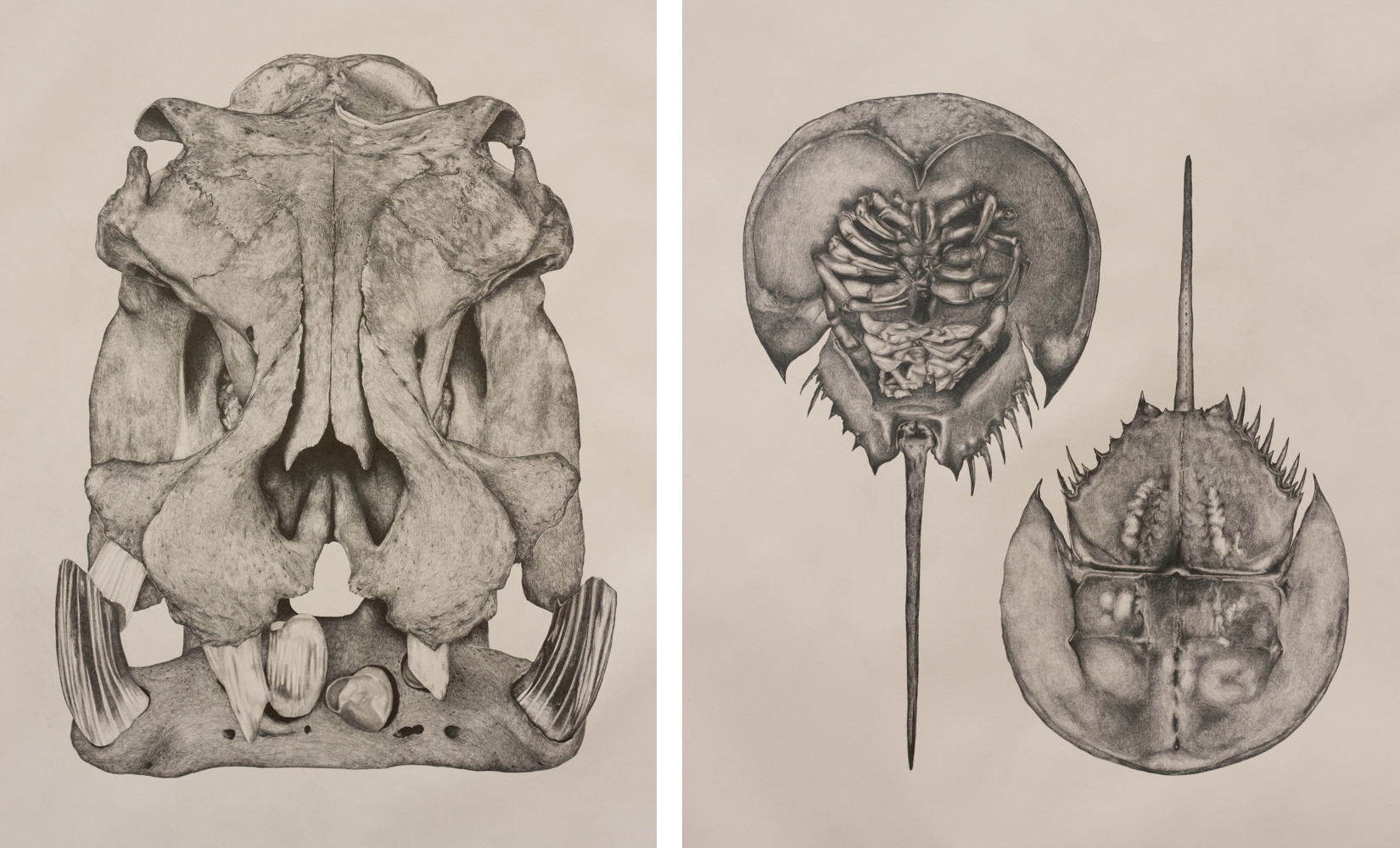

LEFT: Fig. 3. Chris Otley, Hippopotamus, 2012. Graphite on paper, 65 x 85 cm. Photo: © Chris Otley.

RIGHT: Fig. 4. Chris Otley, Horseshoe Crab, 2012. Graphite on paper, 80 x 90 cm. Photo: © Chris Otley.

I have repeatedly sought to achieve a similar feeling of cartographic detail in my drawings, regardless of the scale on which I work. In producing Hippopotamus (Fig. 3), I often thought of meandering river systems as I faithfully transcribed the myriad tiny cracks and fissures in the expansive bone structure. There is also undoubtedly a flattening of form in my approach to this drawing (and my work in general) which aids this feeling; the unfamiliar front-on viewing angle combined with the use of harsh outlines creates island territories, but additionally, when viewed in person, as it catches the light, the bright reflective sheen of thickly layered black graphite can reverse the idea of deep shadow it depicts (Fig. 4). I also work on a drawing board, rather than using an easel, and tend to execute each piece quite mechanically, steadily working from right to left; these approaches assist the flattened aesthetic. The reference photographs I take are often from scientific archives or pieces of museum taxidermy, where, as with maps, efficiency and clarity of display are fundamental to their visual aesthetic. Hunting through the rolling stacks of the Natural History Museum, London, for their few specimens of the now-extinct Rocky Mountain locust was a particularly formative experience. The anachronisms of sleek metal shelving units containing worn, wooden Victorian drawers, each filled with ranks of jewel-like pinned insects and minute, highly-evocative handwritten labels in calligraphic script, all certainly contribute to my drawing practice.

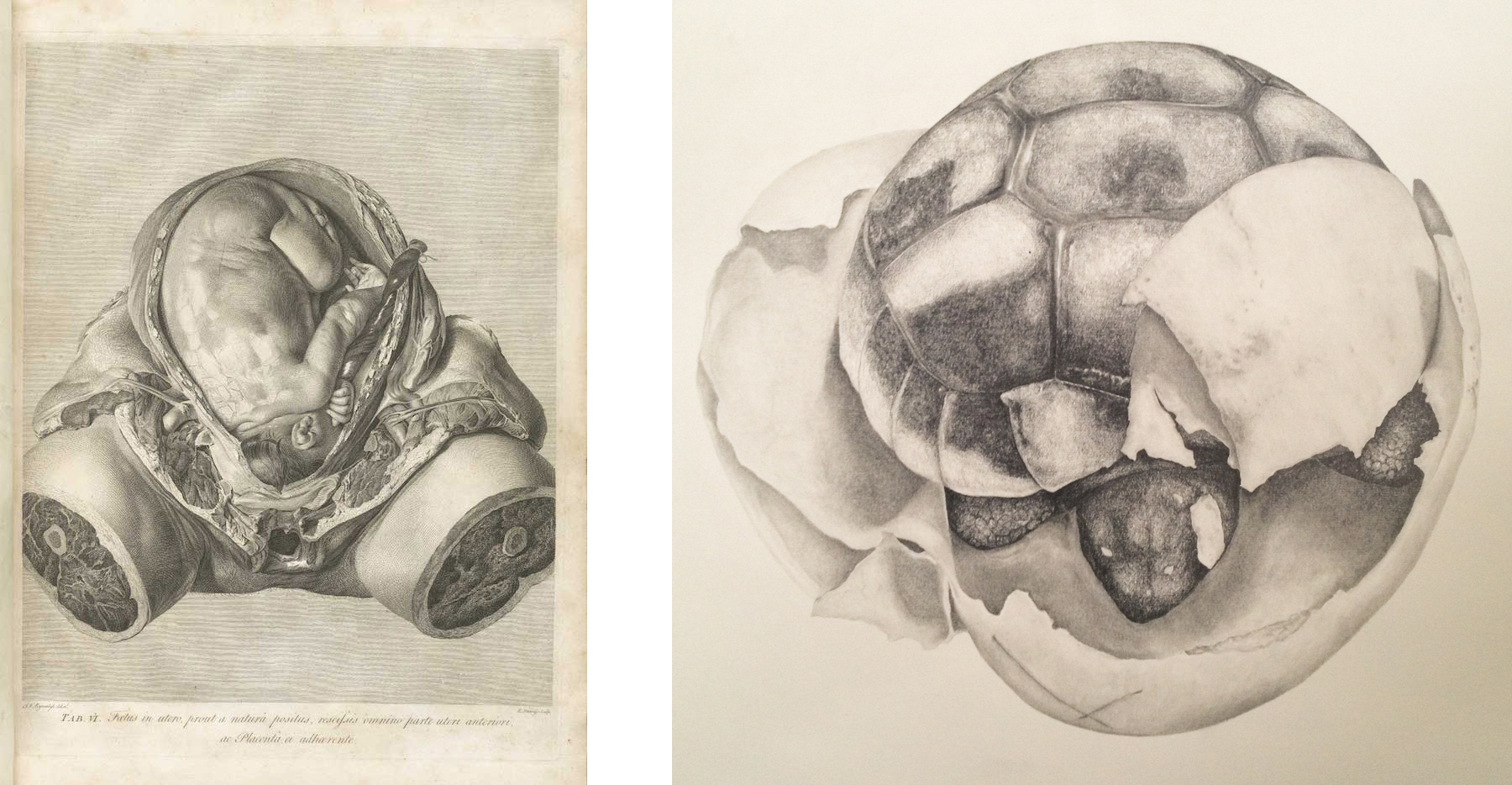

LEFT: Fig. 5. Robert Strange after Jan Van Rymsdyck, Tab. VI: Foetus in utero, engraving from William Hunter, The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, exhibited in Figures (London, 1774). Image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, USA.

RIGHT: Fig. 6. Chris Otley, Tortoise Hatchling, 2012. Graphite on paper, 50 x 40 cm. Photo: © Chris Otley.

The thorny issue of objectivity in didactic anatomical illustration remained of course highly contested throughout the period. For the anatomist William Hunter, “Anatomical figures are made in two very different ways; one is the simple portrait, in which the object is represented exactly as it was seen; the other is a representation of the Object under such circumstances as were not actually seen, but conceived in the imagination,” [3] a division which allowed him to place his illustrations into the former, supposedly superior category of extreme descriptive inclusiveness (Fig. 5). Unflinching details such as individual hairs on the skin, a piece of thread tying-off the cut umbilical cord, or the accidental glistening reflections on the back of the unborn baby are all unnerving, and further enforce the impression of vicarious direct observation, and thus veracity. I rarely choose to “correct” or self-censor incidental details in my own drawings precisely because they imbue a study with the hinted narrative component that is so problematic in Hunter’s illustrations. My humble Tortoise Hatchling (Fig. 6) includes the crucial “X-marks-the-spot” pencil lines hand-drawn onto the base of the shell by the breeder when removing the egg from a dug nest, in order to match its original orientation in the confines of an artificial incubator and ensure its proper development.

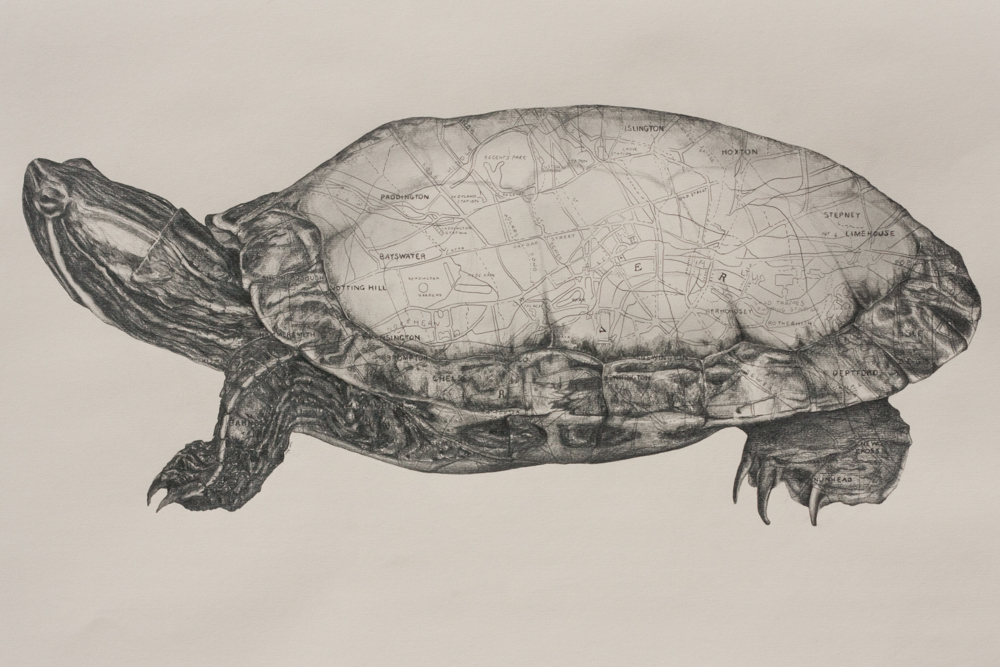

The interconnections found between eighteenth-century travel journals and scientific illustrations remain a great source of interest to me. Artist-scientists deployed both the microscope and the telescope to help record their expedition findings and assert their authority in new territories, both micro and macro: surveying, classifying, circumnavigating, describing and understanding “foreign bodies.” Kay Dian Kriz’s study of Hans Sloane’s travel journal, Voyage to… Jamaica (1707/1725), points to the author’s relentless cataloging of the inhabitants of these new spaces—human, animal and vegetable.[4] Similarly, the structure of Stubbs’ published Comparative Anatomy project in itself reinforces this sense of an anatomical voyage, as the viewer is systematically led through anterior, posterior and lateral views of the human skeletal system, followed by lateral views of that of the tiger and then the common fowl. This format is then repeated to show the intact (or near-intact) body, and once more to present the major muscle tissues—providing a visual tour of each species treated, from the depths of the body out to the surface and back in again. Much more overtly, I have experimented with incorporating hand-drawn copies of period maps merging with my studies of related specimens, as a means of offering some socio-historical narrative to the subject. For instance, in an ongoing series responding to invasive species found in and around London, the Red-Eared Terrapin (Fig. 7) includes a map of the capital’s sewer system (in reference to the 1990s “Ninja Turtles” craze which saw 52 million terrapins exported from the U.S. within a decade). American Signal Crayfish (Fig. 8), a specimen observed at Billingsgate Fish Market, also includes the arms of the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers, one of the Great Twelve City Livery Companies (first awarded a Royal Charter in 1272) who continue to inspect fish imported into the City of London.

Fig. 8. Chris Otley, American Signal Crayfish, 2014. Graphite and gold leaf on paper, 59 x 84 cm. Photo: © Chris Otley.

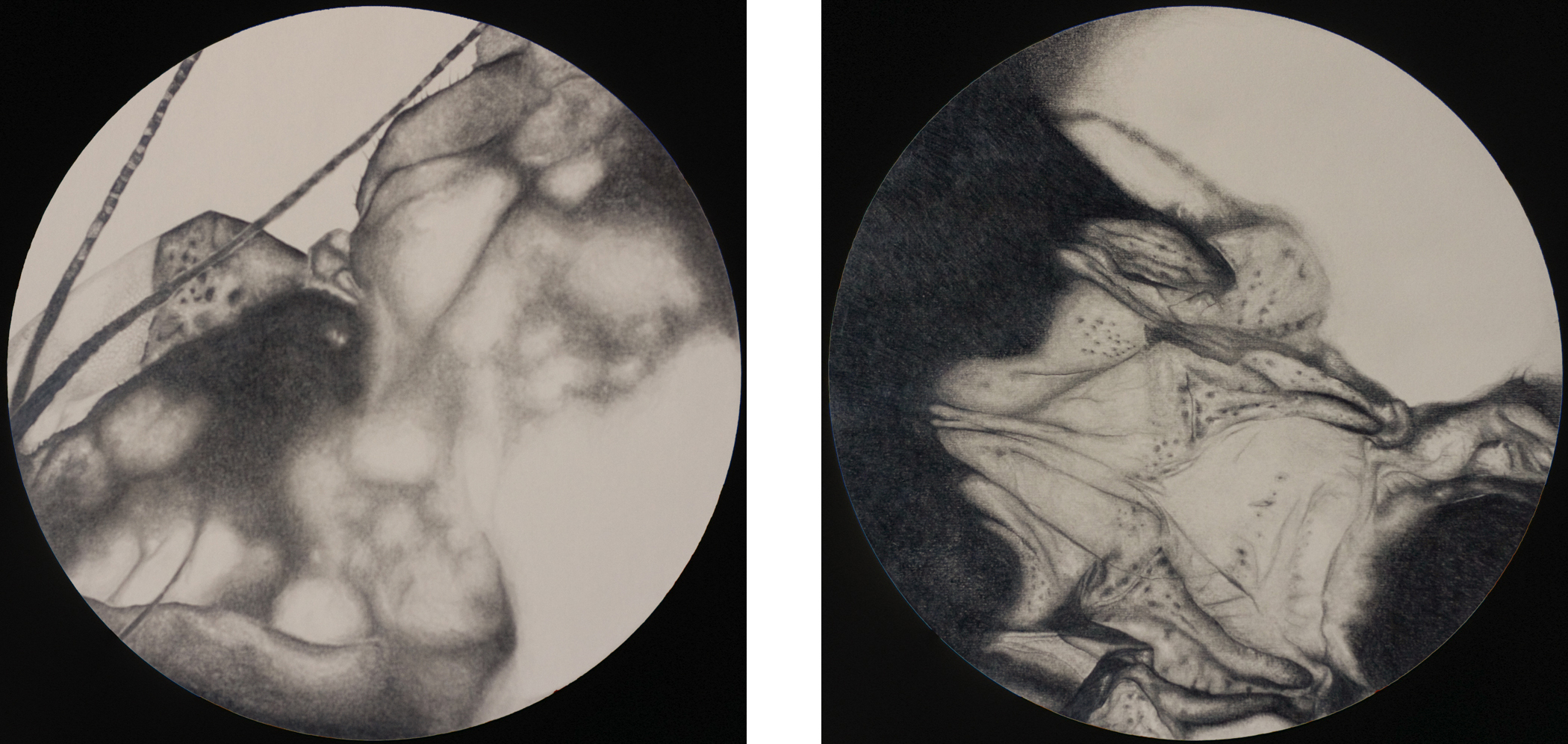

Just as Robert Hooke focuses his lens on both the compound eye of a fly and the surface of the moon, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) repeatedly deploys a conceit of optics in parodying the language and imagery of scientific publication and travel journals. The narrator, a trained surgeon, is disgusted by his close-up view of lice on the Brobdingnag giants’ skin, but then remembers the shock his own face had earlier given to the tiny Lilliputians. For all Gulliver’s empirical observations, by the end of his travels he has lost all perspective. As with Hooke, the visual device offered by a circular frame or crop instantly communicates a conflated idea of peering into another world. I have enjoyed playing with perceptions of scale and confused depths of field in my drawn studies of the shed skins of a praying mantis, as viewed through the lens (Figs. 9 and 10).

LEFT: Fig. 9. Chris Otley, MicroMacro II, 2013. Graphite on paper, 52 x 52 cm. Photo: © Chris Otley.

RIGHT: Fig. 10. Chris Otley, MicroMacro IV, 2013. Graphite on paper, 52 x 52 cm. Photo: © Chris Otley.

Most recently, I have been moving away from realist modes towards a certain abstraction, to further these ambiguities. By the 1790s, the inherently hierarchical language of the scientific comparative gaze, cataloging difference in “foreign bodies” of all kinds, had found itself embroiled with the politics of the anti-slavery movement.[5] Today, the tabloid language of travel, borders, territories, and migration is again heavily politicized and replete with disparaging and genericizing biological and zoomorphic terms. Swarm and Multiply (Fig. 11) presents a swirling mass of details extracted from observations of jellyfish, oil slicks, funghi and the head of a locust. Whether it is planetary or petri dish in scale is left deliberately uncertain.

Fig. 11 Chris Otley, Swarm and Multiply, 2016-2017. Graphite on paper, 60 x 60 cm. Photo: © Chris Otley.

Chris Otley is an artist and Head of Art at Magdalen College School, Oxford; www.chrisotley.com

[1] Some of these issues are explored further in James Christopher Otley, Haunted Bodies: George Stubbs’ Comparative Anatomy (c. 1795-1806) and the Search for Universal Language, MA Dissertation, (Courtauld Institute of Art, 2006).

[2] Robert Hooke, Micrographia, or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made (London, 1665); William Cheselden, Osteographia (London, 1733); William Hunter, The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, exhibited in Figures (London, 1774); George Stubbs, A Comparative Anatomical Exposition of the Structure of the Human Body, with that of a Tiger and Common Fowl (London, 1804-1806) [published prints].

[3] Hunter, Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, Preface.

[4] Kay Dian Kriz, “Curiosities, Commodities and Transplanted Bodies in Hans Sloane’s Voyage to… Jamaica” in Geoff Quilley and Kay Dian Kriz (eds.), An Economy of Colour: Visual Culture and the Atlantic World, 1660-1830 (Manchester and New York, 2003).

[5] I think here of the text and illustrations found in Charles White, An Account of The Regular Gradation in Man, and in Different Animals and Vegetables and From the Former to the Latter. Illustrated with Engravings adapted to the Subject. Read to the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, at Different Meetings, in the Year 1795 (London, 1799). White comments that he was led to his own theories from hearing John Hunter lecture on the “Gradation of Skulls,” a concept which Hunter become so associated with that in his portrait by Reynolds (1786-9, Royal College of Surgeons, London) he is depicted with an open book displaying a range of animal and human skulls.

Cite this note as: Chris Otley, “Artist’s Notes: Drawing on 18th-Century Natural History,” Journal18 (April 2017), https://www.journal18.org/1666

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.