Tong Su

The eighteenth-century Qing court is renowned for its extensive array of colorful artifacts, reflecting a deep-rooted fascination with color that is mirrored in the Manchu language. This attention also extends to color’s absence. Within the Manchu linguistic paradigm, numerous adverse conditions are linked to the loss of color. For example, “fundehun” denotes not only becoming desolate, forsaken, or deserted but also being pallid, ashen, or pale.[1] “Gūwaliyambi” may refer to fainting or breaching but likewise signifies fading in color.[2] Similarly, “wasimbi,” meaning to decline or to die, also conveys the notion of becoming pale and wan.[3]Death is articulated as “bucen,” sharing its etymology with “bucenshūn,” which translates to “deathly pale.”[4] To die is metaphorically to fade in color, reinforcing the conception of color as the essence of life.

The link between color and life is further illustrated by the vital role of color in taxidermy at the eighteenth-century Qing court. Taxidermy, as a hybrid technique, combines organic and inorganic materials to revitalize inanimate objects, attributing significant value to the use of color in the artistic production process. In this context, “taxidermy” refers to a broad spectrum of objects incorporating multi-colored real and faux furs and leathers in their construction, employing specific coloring and staging methods for display. The practice raises questions about the cultural value of placing such emphasis on coloring in enlivening or revitalizing inanimate objects. Demonstrating its widespread appeal in Qing society, taxidermy served various purposes, from wearable fashion and horological art objects to street spectacles, wardrobe accessories, and theatrical props. Notable examples documented in imperial records include a basswood cat designed to deter rodents and a wooden bear coated with leather and oil paints to simulate real fur, both of which belonged to the collections of Emperors Yongzheng (r. 1722-35) and Qianlong (r. 1735-96).[5] More complex creations at the Qing court featured automated taxidermized animal forms, showcasing a fascinating facet of synthetic art production that involves various coloring methods to imbue these inanimate objects with a semblance of life.

Court artists demonstrated remarkable skill in creating lifelike representations through diverse techniques. Although considerable scholarly attention has been devoted to the Qing court’s animal paintings, the fur trade and fashion, and the medical and culinary properties of animal byproducts, the eighteenth-century coloring techniques and their significant roles in revitalizing and enlivening taxidermies, as well as the complex processes behind synthetic arts that blend different mediums—including animal skins, feathers, and horns—have remained relatively understudied.[6] This paper analyzes color as a material process of coloration and highlights the central role of color in enlivening taxidermized artworks. Examining the role of color in taxidermy at the Qing court reveals a melding of resources and methods. The fusion positions the Qing court as a remarkable site of experimentalism, where a unique cosmopolitan culture was meticulously crafted. This experimentalism was characterized by an intense interest in rejuvenating pale or lifeless objects made from animal derivatives, using the elixir of color.

Color Alchemy at the Qing Court

Before being re-enlivened at the court, animal skins, feathers, and horns were sourced from a variety of activities, including hunting, trade, and gift exchange.[7] These objects, primarily obtained through the killing of animals, held significant monetary value. Specific types, such as mink furs (Ma. seke furdehe) and yak horns (Ma. moo ihan i weihe), were prized possessions, forms of currency, and coveted war plunders, as recorded in the Old Manchu Archive (Ma. tongki fuka akū hergen i dangse) since the Tianming reign (1616-26).[8] Furs and leathers, being lightweight and useful, played a crucial role in an economy where the exchange of goods was a primary method of trade.[9] For instance, in the late seventeenth century, Siberian Bukharan merchants served as intermediaries to facilitate barter exchanges between spices and furs, maximizing profits while avoiding the complexities of currency exchange.[10] The utilitarian value of leather coats (Ma. furdehe etuku) made them an essential part of the military uniform on the frontiers during cold weather.[11] While the steppe origin of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) may be a myth that was reinforced in the eighteenth century, its relevance to the living conditions essential to nomadic heritage remains evident.[12]

The forms of these animal byproducts were altered after entering the court. For example, during a 1905 expedition, Japanese anthropologist Torii Ryūzō (1870-1953) discovered two bear taxidermies dated 1754 and antlered chairs from the Chongde reign (1626-36) in the Mukden Palace, Shenyang (Fig. 1).[13] The bears, lying lifelessly on tables with interiors filled with sorghum stalks and straw and pieced together with twine, showed no sign of vitality as they were stored haphazardly among other objects neglected during wartime.[14] This observed deterioration, as captured by the black and white photograph, prompts one to wonder about their original grandeur, the color and lively sheen of their furs at the eighteenth-century Qing court.

The Qing court’s esteemed collection boasted a vibrant array of animal skins and products, included everything from shark skin, sheepskin, and goatskin to cowhide leather, deerskin, bear furs, as well as a wide variety of furs and feathers from various creatures.[15] As these animal derivatives came into custody, the Qing court undertook a transformative act, turning the narratives of the steppe and market into a new narrative: the court workshop’s production process for coloring and transforming them into artful objects. In 1892, Alekseĭ Matveevich Pozdneev (1851-1920), a Mongolist, expedition traveler, and photographer, observed a street scene of leather workshops on Kalgan’s Main Trading Street, located just 200 kilometers from Beijing, where leathers being tanned into various colors were displayed, emitting a distinct scent.[16] Similarly, the pictorial handscroll commemorating the sixtieth birthday of Qing Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661-1722) depicts a specialized leather workshop at the celebration in Beijing, with variously colored hides stretched on frames and furs draped over poles (Fig. 2). In the mid-eighteenth century, the Qing court maintained a stock of organic dyestuffs, such as safflower and indigo, along with tanning equipment, for dyeing fur and leather, resulting in durable, evenly colored materials.[17] This depiction underscores a complex process of dyeing and curing, preparing materials for subsequent use at the court. It offers insight into the role of color in revitalizing organic materials, which were utilized as raw materials for crafting court artifacts that incorporate these preparatory processes.

While some furs and leathers arrived at the court pre-processed with colors, others were further processed and colored in the palace workshops. These various workshops, overseen by the Imperial Household Department, created customized artifacts based on imperial orders.[18] Multiple leather storehouses (Ma. furdehe i namun) at various locations served as major processors of hides. Handicraft workshops across the court received leathers and dyestuffs from these storehouses for each customized order.[19] Artisans were provided with premium materials for making opulent attire such as fur accessories and ceremonial wears, as well as synthetic art pieces like horological machines, and taxidermized props and displays.[20]

Customized artistic creations within the court were meticulously crafted to maximize the use of their given raw materials. Each piece was typically documented with a yellow label attached to the finished product in the court collection. For instance, the yellow label on a leather pouch designed for a fire striker identifies its material as “red smoked leather (hong xunpi)” (Fig. 3). The label refers to a smoke-treatment coloring process: after tanning liquid was applied in batches, the cowhide was stretched, nailed to a frame, and then exposed to smoke to color the leather.[21] The Manchu term “bulhari,” which refers to smoke-treated cowhides, essentially recognizes their colorful appearance. Here, “bulha” signifies embroidery-like, multicolored, or magnificent appearances, and the suffix “-ri” denotes the quality of the referent itself—“bulha.”[22] The smoking process not only enhances the leather’s durability but also imparts a beautifully even and rich red hue, significantly adding value by transforming pale leather into a lively and magnificent appearance. The surface finishing of the leather, characterized by fine creasing, suggests a process where the material was manipulated to soften and accentuate its natural pattern and sheen, effectively revitalizing its essence as if bringing the skin back to life. [23]

The coloring and surface finishing of the leather mark a transformative process, where the vivid color elevates the piece beyond its origins as animal skins, bestowing upon it an animated afterlife after reprocessing and repackaging at the court. The finished fire striker pouch displays an elegant silhouette with three lobes at one edge and graceful neckline curves, evoking images of a burning fire or a blooming lotus. Gift-giving records reveal that a red smoked leather fire-striker pouch, likely similar to this one, was presented by Emperor Yongzheng to Prince Hongjing (1711-77) in 1725 during the New Year.[24] This was probably intended as a gesture to bestow good luck and vitality upon his young nephew. Moreover, a 1781 record indicates that smoked leather fire-striker pouches of various colors, including red, yellow, purple, and black, were placed on altar tables in the Hall of Imperial Longevity (Ma. amba jalafungga deyen).[25] In the hall, portraits of emperors from successive dynasties were venerated, with the finest multi-colored sets displayed to honor the ancestors and pray for the dynasty’s enduring vitality.[26] Objects like this pouch, meticulously crafted from natural elements and subjected to intricate tanning processes, represent a seamless fusion of raw materials with the court artisans’ methods for curing and processing organic matter. The court’s creation of the finest artifacts in multiple color sets seems to carry wishes for longevity and underscores the importance of merging life derivatives with colors to carry forth its life energy. This profound appreciation for colorful objects, made possible by the court’s production process, embodies the belief in color as the essence of life. It invites reflection and a deeper exploration of how the alchemy of color can transform lifeless entities into enduring artifacts at the Qing court.

Color in the Transformation of Life in Taxidermy

To transform lifeless materials into animated taxidermy, a variety of coloring techniques were utilized, extending beyond tanning natural leathers. There was a marked commitment to exploring innovative ways of using color to fuse life into inanimate forms. This effort included the careful selection of synthetic materials that effectively mimic the essence of life, transforming objects into figures that resonate with culturally specific aesthetic sensibilities. The court’s creation of taxidermized animal displays exemplifies these strategies in action.

In 1769, a piece of deer taxidermy intended for use as a theatrical prop in the court theater was crafted using pale kid goatskin and the horn of an unidentified species to create the three-dimensional body of the animal.[27] Patterns resembling deer fur were then painted onto a piece of white twill to simulate real fur. This painted twill pattern was subsequently attached to the goatskin body, resulting in an artifact entirely made from faux materials. While genuine deer skin was certainly available at the court, the intentional choice of mismatched materials suggests a deliberate shift away from using the natural animal body.[28] Faced with an expected lack of anatomical precision, the taxidermized deer instead focuses on its new, painted, and rejuvenated appearance. This method goes beyond mere distinctions between dead animal byproducts and lively representations, illustrating the belief that appropriate color treatments can transform goat material into a convincing depiction of a deer. Although the deer taxidermy no longer exists, the presence of painted elephant and tiger skins on damasks in the palace collection, customized for other purposes, offers insights into how the patterned skin texture of the deer taxidermy might have been executed (Fig. 4). It is conceivable that a range of animal derivatives, including silk from cocoons, goat skins, and horns from unidentified species, were used in combination to vividly recreate other animal species, such as deer, tigers, and elephants. This taxidermy practice highlights the transformative power of color and reinforces the belief that the essence of life, rather than authentic bodily matter, carries life forces.[29]

A similar transformational process of animal forms through taxidermy was evident in another example from 1756. An automated lion, initially covered in furs that became moth-eaten and damaged after two years of use and in need of restoration, had its authentic furs replaced with velvet to mimic its original appearance.[30] The velvet used, characterized by its soft pile and made from dyed silk threads, is a traditional Chinese fabric that originated in Zhangzhou, Fujian Province (hence known as Zhang Velvet).[31] It was mass-produced in Suzhou and Nanjing during the Ming and Qing dynasties. At the Qing court, Zhang Velvet was employed as a faux fur material, with another instance documented in 1757 of its use in creating various objects typically made from actual leathers and furs, including saddles, taxidermies, and tiger costumes for theatrical performers on stage.[32] The wide popularity and acceptance of velvet suggest that imperial commissioners were likely quite satisfied with its capability to blend the artificial with the real.

This preference for velvet also indicates a rigorous pursuit of bright colors and precise color matching, as silk, used for making velvet, generally absorbs dyes more readily and achieves more vibrant colors compared to leather.[33] These qualities allowed artisans to closely match the hue of a lion’s fur. It is conceivable that color exaggeration, such as intensifying the redness of a mane, was employed to enhance their vitality. These “lifelike” colors, achieved through a painterly process of dyeing and painting, were integral to transforming the neutral canvas of an animal’s body form into a convincing living sculpture. Velvet also provides a tactile sensory experience reminiscent of live animals, a quality unattainable with painted twill or damask. It resulted in taxidermized animals that were moveable, pleasant to touch, and entertaining, with bright colors that provided multisensory satisfaction to viewers. The creative potential of velvet was further demonstrated by its use in the imperial-sponsored Suzhou Fabric Workshop for representing furry avian creatures like cranes.[34] In these taxidermized animal forms, a deliberate effort was made to repurpose various materials to create convincingly bright and lifelike imitations of real animals. These advancements in taxidermy techniques underscore the Qing court’s growing fascination with using color across different mediums to infuse objects with the essence of life.

By the eighteenth century, the Qing court had become a hub for mechanical devices, masterfully blending automata with colorful botanical and zoological themes.[35] Metal components provided the mechanical foundation for these automata, whose surfaces were embellished with colored skins and feathers, ingeniously integrating taxidermy with clockwork intricacies. British, Swiss, and French craftsmen working at the Qing court, along with their renowned offshore peers, were widely acknowledged as the creative minds behind the clockwork mechanisms.[36] However, the role of Chinese artisanal expertise, crucial in designing the vibrant, colorful exteriors in line with Chinese aesthetic preferences, has not been adequately appreciated. Collectively, these diverse artistic traditions adeptly created designs that mirrored contemporary animal paintings, transforming them into tangible, three-dimensional artifacts embodying the spirit of contemporary art.[37]

Consider a mechanical clock crafted in France and housed at the Qing court, designed to depict a parrot (Fig. 5). This piece of parrot taxidermy features metallic green feathers on the bird’s head and neck, reminiscent of a peacock, paired with spotted beige back and tail feathers likely sourced from a pheasant species known for their long, fluffy tails and intricate patterns. The combination of colorful feathers from different species creates a miraculously auspicious omen.[38] When activated, the parrot taxidermy simulates singing and animates its head and tail, as if bringing the enigmatic bird back to life.[39] The vibrant plumage bestows upon the parrot a majestic iridescence and elegant posture, invoking the mythical aura of the phoenix, which, according to legend, collects exquisite feathers from a variety of species.

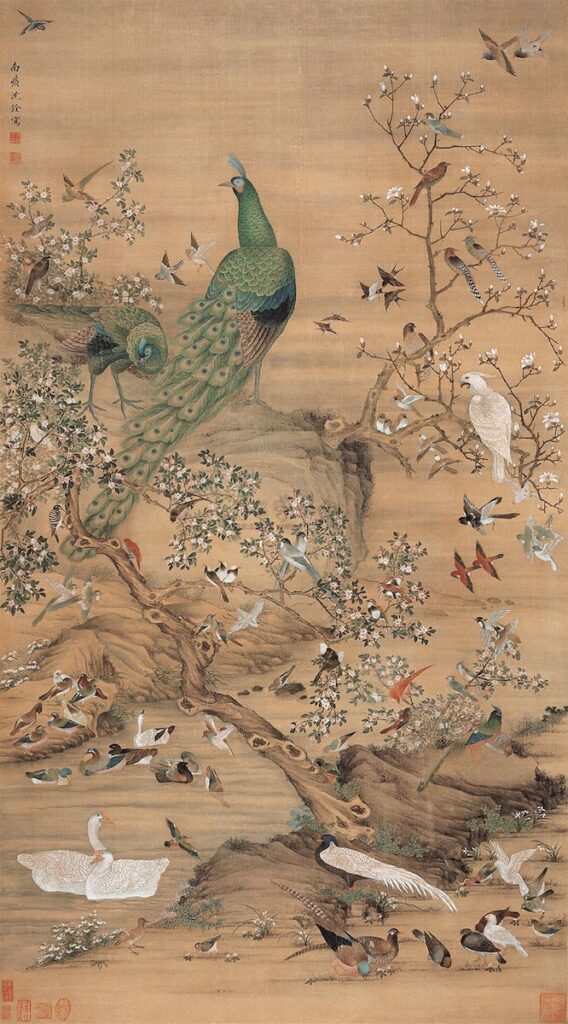

The aesthetic sensibility of the parrot mirrors the style observed in contemporary bird-and-flower paintings, influenced by market demand for detailed and ornately decorative representations of birds.[40] For example, a painting attributed to Shen Quan (1682-after 1762) features a paradisiacal gathering of various bird species (Fig. 6).[41] The birds are depicted in diverse poses, with their bodies rendered in saturated and dense colors that highlight feather patterns. Special attention is given to the direction and angle of feather growth, marking different color parts, and achieving a lifelike replication. This painting’s graphic style distinctively employs color as visual highlights, creating a sense of life against a backdrop of strategically placed rocks and slanting tree branches, rendered in subdued color washes and fine lines to enhance the imagined composition. Similarly, the parrot taxidermy uses color to enhance its painterly paradisiacal appeal and adds a mysterious aura while contrasting sharply with its alien mechanical structure. Themes of paradisiacal bird gatherings and mythical birds were motifs valued both in art markets and at the Qing court, characterized by vibrant feathers and dynamic poses as symbols of vitality. Such themes made these artworks ideal gifts for birthdays and festivals, and they frequently appeared in the gift inventories given to Emperor Qianlong.[42]

The automated animal forms from the Qing court exemplify a harmonious integration of raw materials with innovative processes in coloring and design. They reflect a society dynamically balancing tradition and innovation, driven by an insatiable curiosity. These artifacts, including automated taxidermized forms of deer, lion, and parrot, demonstrate distinct styles in the use of skins and colorful substances. They underscore the Qing court’s continuous and meticulous refinement of raw materials, emphasizing the significance of ongoing curation. In this context, the act of coloration was more than a passive endeavor. It was an active bestowal of value, transforming materials into enduring artifacts and emphasizing their perpetual worth.[43]

Conclusion

This study explores the sophisticated design and staging of colorful, taxidermized objects at the Qing court, illuminating the complex relationship between raw animal derivatives, synthetic handicraft labor, and the use of colorful materials. Specific examples include smoke-treated cowhide purses and taxidermized animal forms created through various coloring methods. Color played multiple roles in bringing these taxidermized objects to life, acting not only as a crucial agent for preserving leathers and furs but also imbuing layers of meaning, effectively breathing life into ephemeral objects. The process of coloration involved a convergence of diverse colored products and knowledge systems, ensuring the preservation of both the materiality and the essence of taxidermized art. This process contributed to the evolving practices of crafting zoological representations at the court, supported by a wealth of artisanal knowledge and material networks. The history of these artifacts unveils the complex interplay between raw materials and synthetic artistic processes, facilitated by color, during the Qing dynasty in the eighteenth century.

This analysis positions the materiality of color as an enduring symbol that captures the fleeting essence of life. Over time, furs and leathers that lack proper curing or coloring inevitably succumb to decay, fading into a pale, dehydrated, and desiccated state, often reducing these raw materials to mere shadows of their former selves (Fig. 7). This natural decay, more than merely marking the passage of time, imparts an evanescent quality to artifacts that carry such a living essence. When objects at the Qing court containing these organic materials exhibited wear or suffered damage, a range of steps were undertaken at the court—from restoration and replacement to auctioning or allowing them to age with dignity.[44] From this perspective, coloration’s role was to facilitate the visual transformation of animal-centric artworks throughout their lifespan. The vulnerability of organic materials underscores the importance and expertise of coloration techniques, utilized to preserve the vibrancy of synthetic artworks as they age: a process central to the artistic endeavors of the Qing court workshops. The court’s meticulous approach to color offers insights into the repurposing, upkeep, lifespan, and cyclical renewal of the relationship between organic matter and synthetic art. It acknowledges the inherent temporality and transformative qualities of nature while celebrating the enduring power of color as the essence of life.

Tong Su is a PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

Acknowledgments: Special thanks are given to Wang Zilin and Guo Fuxiang of the Palace Museum, Beijing, for generously sharing their expertise on Qing court collections, and to He Rongwei of the Liaoning Provincial Archives for providing valuable information on archive collections. Deep appreciation is also directed towards the editors, Ewa Lajer-Burcharth and Thea Goldring, for their invaluable insights and meticulous editing advice. Furthermore, gratitude is expressed for the constructive feedback and genuine revision suggestions provided by the anonymous reviewers.

[1] Jerry Norman, A Comprehensive Manchu-English Dictionary (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2013).

[2] Norman, A Comprehensive Manchu-English Dictionary.

[3] Norman, A Comprehensive Manchu-English Dictionary.

[4] Norman, A Comprehensive Manchu-English Dictionary.

[5] Zhongguo diyi lishi dang’an guan and Xianggang Zhongwen daxue wenwu guan eds., “Mu zuo 木作,” Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu dang’an zonghui 清宫内务府造办处档案总汇, 55 vols (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 2005), 1:212; Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., “Ruyi guan如意馆,” Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 37:130.

[6] For example, He Bian, Know Your Remedies: Pharmacy and Culture in Early Modern China (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020); Yu-chih Lai, “Images, Knowledge, and Empire: Depicting Cassowaries in the Qing Court,” The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly 29, 2 (2011): 1-75.

[7] Lai Huimin 赖慧敏, “Qing Qianlong chao Neiwufu de pihuo maimai yu jingcheng shishang 清乾隆朝内务府的皮货买卖与京城时尚,” The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly 故宫学术季刊 21, 1 (2003): 101-34; Lai Huimin and Wang Shiming 王士铭, “Qing zhongye qi minchu de maopi maoyi yu jingcheng xiaofei 清中葉迄民初的毛皮貿易與京城消費,” The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly 故宫学术季刊 31, 2 (2013): 139-78; Alekseĭ Matveevich Pozdneev, Mongolia and the Mongols, 2 vols(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1971), 1:713; Wan Yi 万依, Wang Shuqing 王树卿, and Liu Lu 刘潞, Qingdai Gongting shi 清代宫廷史 (Tianjin: Baihua wenyi chubanshe, 1990), 87-8; Wang Yongbin 王永斌, Beijing de shangyejie he laozihao, 北京的商业街和老字号 (Beijing: Yanshan chubanshe, 1999),404-7.

[8] The Old Manchu Archive (tongki fuka akū hergen i dangse) chronicled eventsduring the Tianming (1616-26) and Tiancong (1626-35) reigns and was drafted before the Qing Dynasty assumed rulership. The original copies were written in old Manchu script without circles or dots (diacritics). During the Qianlong period, they were recopied using standard Manchu script, which include circles and dots (tongki fuka sindaha hergen i dangse). Zhongguo diyi lishi ed., Dorgi yamun asaraha manju hergen i fe dangse 内阁藏本满文老档, 20 vols (Shenyang: Liaoning minzu chubanshe, 2009), 1: 1-12.

[9] “Sunja nirui ejen Tulkun, aisin menggun (金银), suje gecuheri (绸缎), moo ihan i weihe (牦牛角), mocin (毛青布), samsu (翠蓝布), seke furdehe (貂裘) gidafi gamame somiha be bahafi, alaha manggi.” Zhongguo diyi lishi ed., Dorgi yamun asaraha manju, 20 vols, 2: pamphlet 10, 447.

[10] Mikhail Iosifovich Sladkovskiĭ, Xiu Fenglin trans., Xu Changhan ed., Eguo geminzu yu Zhongguo maoyi jingji guanxi shi: 1917 nian Yiqian 俄国各民族与中国贸易经济关系史: 1917年以前 Istorii͡a torgovo-ėkonomicheskikh otnosheniĭ narodov Rossii s Kitaem (do 1917 g.) [1974] (Beijing: Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe, 2008), 121.

[11] “Tuweri dosime, erin beikuwen oho manggi, urunakuu furdehe etuku dasatara be baibumbi.” Lai Bao 来保, et al. eds., Gin chuwan i babe nechihiyeme toktobuha bodogon i bithe 平定金川方略, manuscript from National Palace Museum, Database of Rare Books, 18th century [Qianlong edition].

[12] For ideological constructions of Qing empire, see Pamela Crossley, A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); Nicola di Cosmo, Military Culture in Imperial China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009).

[13] University Museum, University of Tokyo, Catalogue of the Type Specimens Preserved in the Herbarium of Department of Botany in the University Museum, no. 18 東京大学総合研究資料館標本資料報告第18号 (Tokyo: University Museum, University of Tokyo, 1990); Shengjing Neiwufu 盛京內務府, Feilongge gongzhu qiwu qingce 飞龙阁恭贮器物清册, manuscript from Liaoning Provincial Archives, 1847. Liaoning Sheng Dang’an Guan; Torii Ryūzō 鳥居龍蔵, “Manshū ni okeru jinruigakuteki shisatsu dan 満洲に於ける人類学的視察談,” Torii Ryūzō zenshū 鳥居龍蔵全集, 13 vols. (Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, 1975), 9: 560.

[14] Li Li 李理, “Wangong lie xiongpi, yiwu zhao huanggong: Shenyang gugong jiucang Qinggong xiongpi jiqi xiufu 弯弓猎熊罴,遗物昭皇宫:沈阳故宫旧藏清宫熊皮及其修复,” Gugong xuekan 故宫学刊, 7 (2011): 253-63.

[15] The court collection of animal skins includes “鲨鱼皮、红羊皮、红牛皮、鹿皮、鹿腿皮、带毛鹿腿皮、带毛黄羊腿皮、牛犊皮、撒林皮、貂皮、孔雀皮、八哥皮、鹦鹉皮、鸾皮、十锦雀皮等.” Li Hongwei 李宏为, “Appendix 7,” Qianlong yu yu 乾隆与玉, 2 vols. (Beijing: Huawen chubanshe, 2013), 2: 661.

[16] Pozdneev, Mongolia and the Mongols; Hou Jianzhi 侯鉴之, Ma Hetian 马鹤天, Xibei manyouji: Qinghai kaochaji 西北漫游记: 青海考察记. (Lanzhou: Gansu renmin chubanshe, 2003), 190-1.

[17] The list of natural dyes and mordants includes “红花, 靛青, 大黄, 蘇木, 黃櫨木” among others. Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 21: 553-4; Gugong bowuyuan, ed., “Guangchu si 广储司,” Qinding zongguan Neiwufu xianxing zeli 钦定总管内务府现行则例, 5 vols. (Haikou: Hainan chubanshe, 2000) 3: 353; Sun Jian et al., eds., Beijing gudai jingjishi 北京古代经济史 (Beijing: Zhongguo renmin daxue chubanshe, 2016), 241-2; Lai Huimin, “Qing Qianlong chao Neiwufu,” 101-34; Yu Fei’an 于非闇, Zhongguo hua yanse de yanjiu 中国画颜色的研究 (Beijing: Zhaohua meishu chubanshe, 1955); Guangchu si piku 廣儲司皮庫, “Wei llingqu shuzuo pizhang dagang shi 為領取熟做皮張大缸事,” manuscript from The First Historical Archives of China, 1797.

[18] In certain areas, such as Uriankhai, as discussed by Jonathan Schlesinger, the Qing court preferred naturally colored and high-quality sables (Ma. da bocoi sain seke) over dyed or traded pelts. However, what Schlesinger does not consider are the pre-processed furs and leathers, which suggest a less clear provenance and point to more globalized trade and synthesized production that had less to do with territorialization. Jonathan Schlesinger, A World Trimmed with Fur: Wild Things, Pristine Places, and the Natural Fringes of Qing Rule (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017), 151.

[19] The Department of Armaments and Military Provisions operated specialized workshops dedicated to the production of leather boots, felt, dyes, and other goods. Historical records offer precise information about these establishments. Established in 1676, the South Saddle Storehouse (also known as the internal storehouse) of the Department was situated at the southern corner tower of the Gate of Manifesting Virtue. Meanwhile, the North Saddle Storehouse (also referred to as the external storehouse) was located to the north of the city, just beyond the Gate of Eastern Splendor. Yu Minzhong 于敏中 (1714-1779) and Zhu Yizun 朱彝尊 (1629-1709), Rixia jiuwen kao 日下旧闻考 (Beijing: Guji chubanshe, 1981), vol. 41;Miao Quansun 缪荃孙 (1844-1919) et al., compiled, Guangxu Shuntianfu zhi 光绪顺天府志, in Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng 中国地方志集成 (Shanghai: Shanghai shudian chubanshe, 2021); The tea storehouse contained various items, including cat skins, python skins, goat skins, ram horns, ivory, and tortoise shells. Sun Jian et al., eds., Beijing gudai jingjishi; Gugong bowuyuan, ed., “Guangchu si,” 353.

[20] Located at the southwest corner tower of the Hall of Supreme Harmony and the east wing of the Hall of Preserving Harmony, the storehouse held an array of items. These included furs from foxes, martens, lynx cats, sea otters, and snow weasels. Additionally, it housed imported fabrics such as drugget and serge, satin produced in Suzhou, Tibetan wool, carpets from Shanxi, camlet, ivory, rhino horn, and summer mats. Zhang Naiwei 章乃炜, Zhang Tangrong 章唐容 and Miao Donglin 缪东霖, Qinggong shuwen 清宫述闻 (Taibei Xian Yonghe Zhen: Wenhai chubanshe, 1969); Qi Meiqin 祁美琴, Qingdai Booi Qiren yanjiu 清代包衣旗人研究 (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 2019).

[21] Zhang Yang, Pige wenwu baohu yanjiu 皮革文物保护研究 (Hefei: Zhongguo kexue jishu daxue chubanshe, 2020), 34-5; Chengdu gongxueyuan 成都工学院, ed., Pige gongyi xue 皮革工艺学 (Beijing: Zhongguo caizheng jingji chubanshe, 1961), 192.

[22] Norman, A Comprehensive Manchu-English Dictionary; Robert William Autry, “Manju Tacire: Learning Manchu, an Introduction to the Manchus and Their Language” (MA thesis, The University of Arizona, 2019), 71.

[23] Leather accessories underwent a variety of finishing embellishments, depending on the types of leather and their intended purposes. These processes included stretching, kneading, fire curing, and painting with pigments and varnishes for either matte or glossy finishes that were referred to as “退光漆” and “龍罩漆,” respectively. Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds, Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 7:342; Yongbin, Beijing de shangyejie, 404-7.

[24] Tie Yuan 铁源 and Li Guorong 李国荣, eds., “Shangyong dibu 賞用底簿,” Qinggong Ciqi Dang’an Quanji 清宫瓷器档案全集, 52 vols. (Beijing: Zhongguo huabao chubanshe, 2008), 1:38.

[25] Tie Yuan et al., eds., Qinggong Ciqi Dang’an Quanji, 36:378.

[26] Jian Songcun 簡松村, “Jingshan Shouhuang dian: tan Qingdai dihouxiang yizhi an 景山壽皇殿—談清代帝后像移置案,” Gugong wenwu yuekan 故宫文物月刊, 9 (1983): 49.

[27] Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 32:651-2.

[28] Li Hongwei, “Appendix 7,” Qianlong yu yu, 2:661.

[29] Ma Yunhua 马云华, “Qinggong jiucang foyi kao 清宫旧藏佛衣考,” Palace Museum Journal, 5 (2022): 111-21; Ma Yunhua, “A Textual Research on the Making and Management of Qing Palace’s Buddhist Costumes in the Qianlong Period 乾隆时期清宫佛衣的制作与管理考述,” Journal of Gugong Studies, 23 (2022): 360-71.

[30] Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 21:637. In Buddhist Temples, however, authentic furs seemed to be preferred as exorcistic taxidermy. In 1761, General Jilin from northeast China dispatched ten bear furs. By 1766, a restoration record indicates that new furs were added to repair previously damaged sections. Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., “Jishi lu 记事录,” Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 30:314-5. In 1755, the imperial Buddhist Temple Yonghegong Palace showcased two bear taxidermies sourced from the court painting workshop at Qixiang Palace 启祥宫. These bears had been hunted in the paddock just a year earlier. Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., “Ruyi Guan 如意馆,” Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 21:298-9; 31:808. In 1768, Ruyi Guan received correspondence from the Yonghegong Palace indicating that two bears and four tigers on display in the Dharma Protector Hall showed significant signs of wear, including insect damage and fur loss. The restoration required thirty complete bear skins, inclusive of the head, tail, and claws. Despite having placed an order with General Jilin for these materials in 1766, the palace workshop had not received them by 1770. Consequently, an alternative solution was proposed: Ruyi Guan was instructed to strip the decayed bear skin and paint the taxidermy’s wooden body using oil paints. However, the task encountered delays. By 1773, the Yonghegong Palace dispatched another letter, expressing their concerns. The furs of the displayed animals continued deteriorating, and the bears, despite multiple reminders over three years, remained unpainted. Even a prior request to standardize the size of the two bears had gone unaddressed. Furthermore, after the restoration of the tiger’s teeth and claws in 1771, they showed indications of mold, moisture damage, insect infestation, and further deterioration, necessitating another round of repairs two years later. Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., “Yonghe Gong laiwen 雍和宫来文,” Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 36:860.

[31] Qian Xiaoping 钱小萍, Bai Lun 白伦, Zhongguo gujin sangcan sichou jiyi jinghua 中国古今桑蚕丝绸技艺精华 (Suzhou: Suzhou daxue chubanshe, 2021), 402-4.

[32] Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu, 22:750.

[33] Qian Xiaoping, Bai Lun, Zhongguo gujin sangcan, 402-4.

[34] Sun Pei 孙珮, Suzhou Zhizao Ju zhi 苏州织造局志[1696](Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2015).

[35] Guo Fuxiang 郭福祥, “Shinian lai gongting zhongbiaoshi yanjiu pingshu 十年来宫廷钟表史研究述评,” Gugong xuekan 故宫学刊, 12 (2014): 403-15.

[36] Patek Philippe, Le miroir de la séduction: prestigieuses paires de montres “chinoises” (Geneva: Patek Philippe Museum, 2010); Guo Fuxiang 郭福祥, “European Timepiece Craftsmen in the Imperial Workshop of the Qing Palace 清宫造办处里的西洋钟表匠师,” Gugong xuekan 故宫学刊, 1 (2012): 171-203.

[37] Christian Bailly and Sharon Bailly, Oiseaux de bonheur: tabatières et automates (Geneva: Antiquorum Editions, 2003).

[38] Animals that combine body parts from other animals were considered auspicious omens. For another example of a handscroll painting, see Zouyu tu 騶虞图, collected by the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

[39] Liao Pin 廖频, ed., Qinggong zhongbiao jicui: Beijing Gugong zhencang 清宫钟表集萃: 北京故宫珍藏 (Beijing: Waiwen chubanshe, 2002), 180; Li Zefeng 李泽奉, Liu Ruzhong 刘如仲, Lu Yanzhen 陆燕贞, eds., Zhongbiao jianshang yu shoucang 钟表鉴赏与收藏 (Changchun: Jilin kexue jishu chubanshe, 1994), 110.

[40] Caitlin Karyadi, “The Making of Shen Nanpin (1682-ca. 1760): Painting, Collecting, and Canonizing in Japan and China” (Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 2024).

[41] Karyadi noted that some Japanese painters, including Tani Bunchō 谷文晁 (1763-1840), would create paintings attributed to Shen Quan or in the names of other bird-and-flower painters, as there was an established framework for appreciating their styles. Karyadi, “The Making of Shen Nanpin,” 67.

[42] For example, Emperor Qianlong received various paintings known as “a hundred birds 百鸟图” as birthday gifts, illustrating their use as auspicious tributes. In 1736, Prince Yunlu (1695-1767) presented a painting of a hundred birds by the Song painter Huang Quan (903-65). The emperor also received a handscroll painting of a hundred birds, attributed to the Ming painter Lu Zhi (1496-1576), from Anhui Governor Feng Ling in 1767. Additionally, in 1770, Prince Yanhuang (1691-1771) gifted another painting depicting a hundred birds paying tribute to a phoenix, attributed to Huang Quan. In 1785, Kong Xianpei (1756-1793), a prominent member of the Kong family and Confucius’s seventy-second generation descendant, presented another painting by Huang Quan of a hundred birds. Tie Yuan et al., eds., “Gong’dang jindan 贡档进单,” Qinggong Ciqi Dang’an Quanji, 9:89-90, 10:292-3, 26:173-4.

[43] Wang Xiang 王翔, Zhongguo jindai shougongye shigao 中国近代手工业史稿 (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 2012), 479-80.

[44] For detailed records on the repair, sale, and discard of court objects, see Zhongguo diyi lishi et al., eds., Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu.

Cite this article as: Tong Su, “Color in Taxidermy at the Eighteenth-Century Qing Court,” Journal18, Issue 17 Color (Spring 2024), https://www.journal18.org/7220.

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.