Dipti Khera

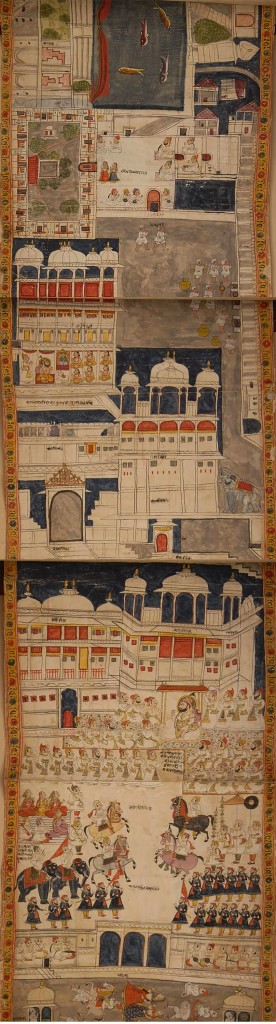

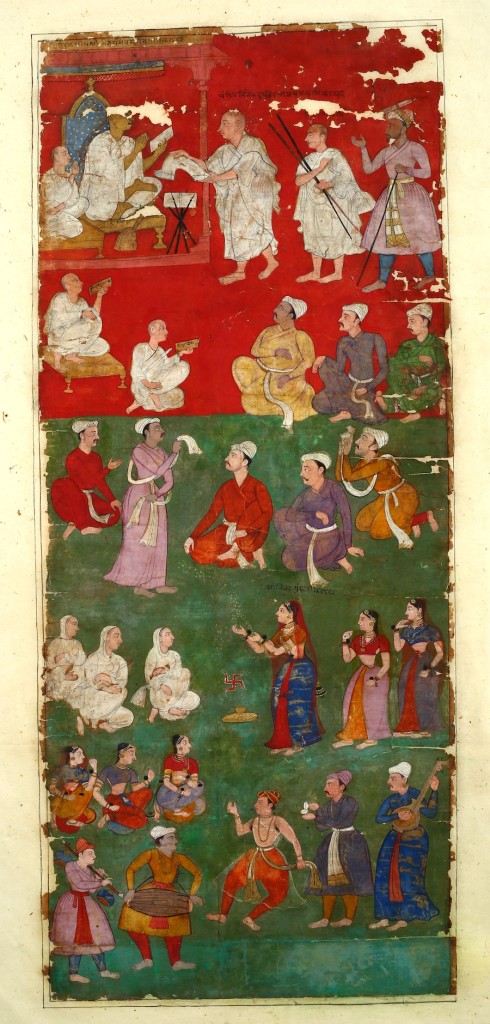

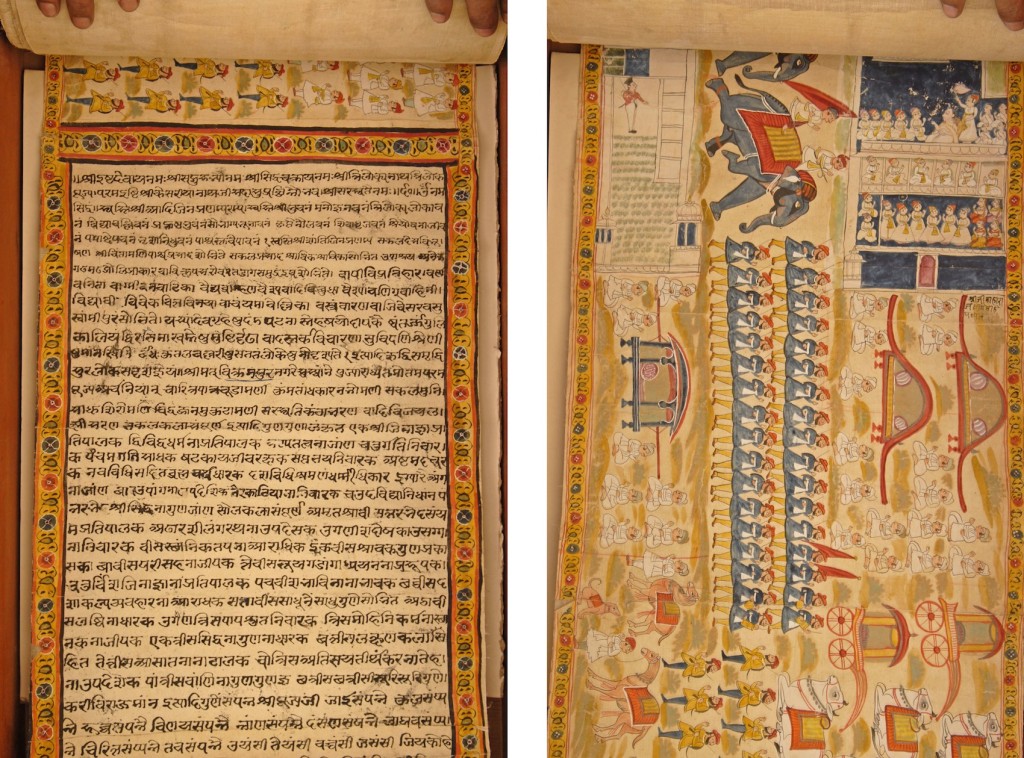

Fig. 1. Unknown artist, Detail from Udaipur Vijnaptipatra, 1830. Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, 2194.6 x 27.9 cm (72 feet by 11 inches). Bikaner: Agarchand Jain Granthalya, Bikaner.

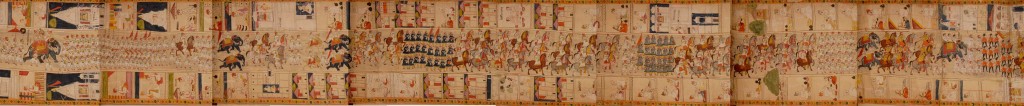

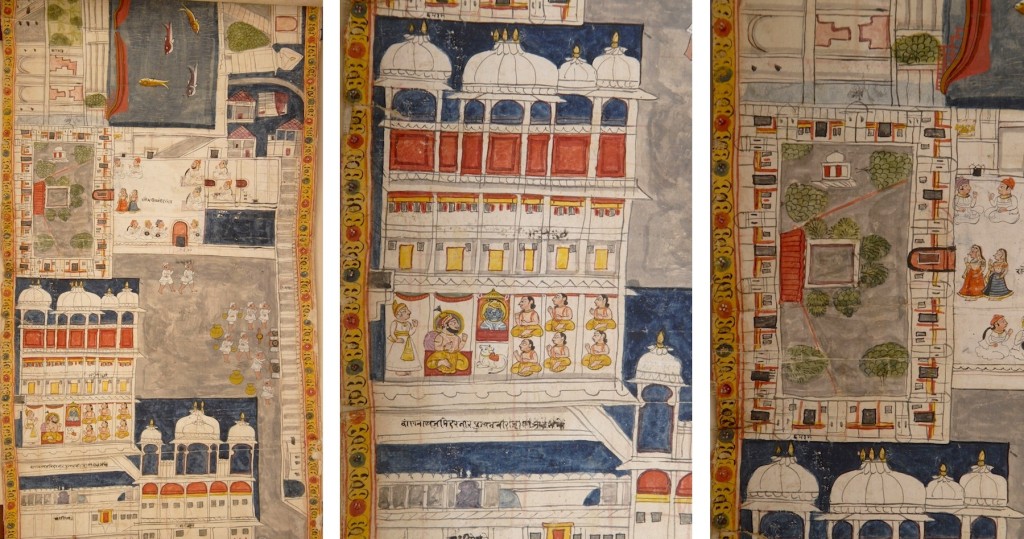

In 1830, the king of Mewar and a group of local merchants residing in the regional court’s capital city of Udaipur jointly sent a signed painted scroll, 72 feet long and 11 inches wide, as an invitation letter (vijnaptipatra) to an eminent monk of the Jain religious community, Shri Jinharsh Suri (Fig. 1). They requested that Jinharsh Suri spend the next monsoon season in their vibrant city in northwestern India. Along the length of this paper scroll, within the first 65 feet, an unnamed artist from Udaipur who was knowledgeable of the pictorial style practiced by its court artists creatively mapped a principal street of the city, painting the important palaces, temples, and bazaars. He further depicted an elaborate procession comprising the Udaipur ruler Jawan Singh and the British Colonial Agent Alexander Cobbe, creating an unusual and innovative dual-axis along which the viewer’s gaze constantly roves to see and understand this scroll. Towards the end of the painted part of the scroll, the artist has pictured the British residency with carefully depicted green lawn-courtyards and inhabitants seated in chairs, thus marking differences between the lifestyles of the British agent and the Udaipur ruler (Fig. 2). Yet, it is important to note that Udaipur’s suburban frontiers, beyond the city walls, are not dominated solely by the British presence. On the other side of the central street, the artist has pictured and labeled the assembly to be held by the invited Jain pontiff akin to a courtly gathering.

LEFT: Fig. 2. Assembly held by the invited Jain pontiff Jinharsh Suri and the British Residency. Detail of Fig. 1.

RIGHT: Fig. 3. Scribes Pandit Rukhabdas and Khusalchand, End of the textual letter and signatories in a variety of handwritings. Detail of Fig. 1.

A vijnaptipatra was made in order to travel, and to encourage and facilitate travels by circulating the urban imaginary of a city as a thriving place – politically, culturally, religiously, and economically. A vijnaptipatra was addressed to eminent Jain monks who led extremely mobile lives. The custom of sending vijnaptipatra scrolls practiced by the Shvetambara Jains owes its origin to the idea of performing pious deeds in the future.[1] By sending such scrolls, prominent merchants of the local Jain community hoped to entice pontiffs to spend the upcoming monsoon season (chaumasa) in their town, for the pontiff’s acceptance of the travel invitation would bring prestige to both the place and its citizens. The scribes of the 1830 vijnaptipatra, pundits Rukabhdas and Kushalchand, reveal this desire in the four-foot-long invitation letter they wrote on the other end of the scroll. The last three-foot section of the scroll preserves the signatures of more than twenty-five prominent merchants of Udaipur (Fig. 3). The attached letter eulogized the invited monk, and concludes by emphasizing that the devotees, residents, and ruler of Udaipur were eager to welcome him. The final pictorial vignette of the scroll, however, shows that the artist rather than the letter writers has imagined that this invitation would be effective – its objective realized by the pontiff’s advent. The artist could also be seen as directing the invited Jain pontiff to imagine himself in a position of authority when he arrives in Udaipur.

This essay turns to the 1830 Udaipur vijnaptipatra as an exemplary object that opens up a critical conversation on the relation between marginality, mobility, and the multilayeredness of objects in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[2] Based on the nineteenth-century writings of James Tod, the first British colonial agent based in Udaipur (from 1799-1822), dominant historiography on northwestern India has focused on Rajputs, the ruling classes of Rajasthan who claimed the warrior Hindu caste (kshatriya) and fashioned themselves as the region’s righteous Hindu kings.[3] Art historians, too, have followed this framework in evaluating artistic cultures that flourished in royal spaces, with the Mughal imperial workshop at the center and regional Rajput court workshops at the periphery. This scholarship has been imperative for asking questions about artistic mastery in ateliers, the relationship between courtly aesthetics and intercultural kingly ethics, and the making of connoisseurs in early modern India. However, artists and literati who offered their perspectives within such visually, materially, and ontologically complex objects as vijnaptipatra scrolls have frequently been sidelined as makers of lower-quality art both by scholars of Indian painting and by those who tend to treat the Jains as an insular community. For scholars of the global eighteenth century, a vijnaptipatra does not offer a desirable social biography that includes long-distance mobility and the associated accruing of meaning that we attach to an object passing through multiple hands across geographical boundaries.[4] Nor do these scrolls present a pictorial field rich in easily recognizable cross-cultural hybridity of the sort seen in other European-Indian artistic encounters from the same time period.[5] Rather, a vijnaptipatra occupies a more liminal space of regional and local, shorter-distance circulation within eighteenth-century pilgrimage circuits and bazaars. It is this space – one on the margins of objects like crafted Indian textiles and flavored Indian spices that were globally sought; and on the margins of imperial and courtly arts that were imbued with a higher aesthetic value within regionally connected courtly cultures – that I propose is worthy of our focused attention.

The questions I ask engage with the current reorientation of the long eighteenth century in South Asia, a time period following the decentralization of the Mughal empire after Aurangzeb’s death in 1707. It continues through the 1830s, when forms of colonial economy and colonial modernity gain ground on the subcontinent, especially in the British entrepôts of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, prior to the establishment of a centralized British empire in 1857. By the 1830s, the British had integrated regional Indian courts like Mewar into their territory as princely states under indirect rule, a political arrangement that led to locally specific enactments of colonial authority.[6] One important impetus for reevaluating the long eighteenth century in India lies in questioning the interrelated, homogeneous arrival of (European) modernity, science, and knowledge with the firm establishment of the British Empire during the mid-nineteenth century, a change largely framed as inevitable and imperative in British accounts.[7] Discussions of the beginning of an early modern epoch in both Asia and Europe underscore that the time period between c. 1500 and 1800 was characterized by long-distance travel and new geographical discoveries; expanding mercantile networks and imperial territories; and the mobility of people and things and associated cross-cultural encounters, the making so to speak of the global at an unprecedented scale.[8] The networks and travels of pan-Indian merchants, petty traders, itinerant religious men such as fakirs and sanyasis, and a range of mobile intellectuals – from artists, scribes and poets to performers and storytellers like bhopas and madaris – equally question the view that “the advent of colonialism completely modified the conditions of circulation in the subcontinent.”[9] Modernity, as seen through markers like historical consciousness, self-fashioning, travel narratives, and the rise of the individual in Europe, was not shaped by exclusions but rather by connections with people, objects and ideas of the world. Historians of South Asia, among them Sheldon Pollock, have stressed the greater importance of articulating India (and other places in Asia, Africa and Americas) into a “world of historical synchrony, not into a world [of] conceptual symmetry.”[10] The current re-focus on the eighteenth century thus questions the all-encompassing displacement of pre-colonial forms. It draws distinctions between early modern encounters which led to new artistic expressions by local and foreign actors and the mid to late nineteenth-century colonial encounters that included hybrid translations of modernity and resistance.[11]

The way in which artistic and mercantile communities employ translocally and transregionally mobile religious objects like a vijnaptipatra to make historical, political and religious claims enables us to think precisely of the currency of early modern texts and objects in an emergent colonial space.[12] It is not surprising that James Tod viewed the Sisodia Rajputs of the Mewar court as the foremost Hindu kings with deep genealogical roots in ancient India, who by the eighteenth century had taken to hedonism.[13] The 1830 vijnaptipatra, contrary to the accounts of British political agents, praises Udaipur: it represents the city as a flourishing and attractive place, thereby exhibiting how artists, alongside scribes and poets, forged alternate historical memories and urban imaginaries during this time period. The artist of the scroll adapts and reimagines this visual-literary epistolary genre and sets new boundaries for the effective work that affective objects – conceived as multilayered and mobile, yet deemed marginal to the canon today – could do in the spheres of diplomacy, religiosity, knowledge production, and territoriality. In their role as traveling objects depicting prosperous bazaars that circulated on the behest of Jain merchants, a vijnaptipatra encapsulates artistic practices of mixing, adapting, and subverting. Therein lies an opportunity for a broader discussion on art and material culture emanating from the bazaars and pilgrimage trails of early modern and colonial India.

Vijnaptipatra: (Re)presenting Mobile and Multilayered Objects from the Bazaar

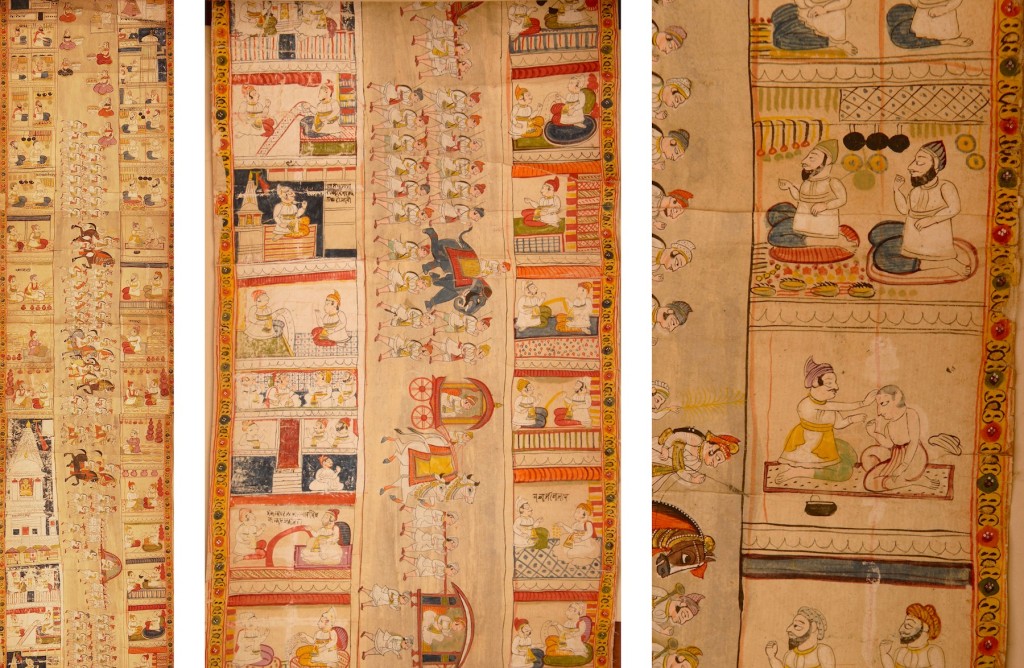

A vijnaptipatra pictorially represents the kinds of painting and scribal practices that flourished on the margins of early modern court workshops. While we have invitation letters dating to the fourteenth century and onwards, vijnaptipatra – as a material object in the form of a long, rolled painted scroll ending with a letter – became particularly popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[14] The study of the corpus of painted vijnaptipatra sent over the course of the eighteenth century from the Marwari town of Sirohi has been critical in understanding the tenets of the genre. Artists represent the town of Sirohi in a consistent painterly style through pictorial vignettes like those of the bazaar, a monk’s assembly, laymen, and courts of regional polities. In many examples of painted scrolls sent from towns and cities in Rajasthan and Gujarat, the artists, like the scribes who composed the letter, cited images from an established canon without necessarily particularizing pictorial references to represent sites of a specific place. However, they almost always employed regional painting styles.

The Agra vijnaptipatra (1610) is an early example of a painted invitation letter that has captured the attention of art historians (Fig. 4).[15] The scroll’s artist Salivahan employed the pictorial idiom of a “jharoka portrait” emergent in Mughal Painting, that is, a window or a pavilion in an assembly hall where the Mughal emperor was seen by the court’s constituents, to compose the portrait of emperor Jahangir. Even a cursory examination of Udaipur vijnaptipatra sent in 1742, 1774, and 1795 demonstrates how Udaipur artists adapted pictorial vignettes from horizontal court paintings to fit the vertical format of the scroll, carefully citing prevalent artistic styles and contemporary portraits of Udaipur rulers (Fig. 5).[16] Representation of palatial architecture was a central pictorial concern in Udaipur court painting, so it is not surprising that local artists saw a Jain vijnaptipatra as an apt visual space in which to experiment and extend their interest in depicting their city.[17] Thus beyond a consideration of Jain invitation letters simply as artifacts that give information on important monks and historical events lies an important story of how such objects played a central intermediary role and participated in circulating painted subjects, forms, and tropes beyond courtly and imperial circles. [18]

LEFT: Fig. 4. Salivahan, Emperor Jahangir’s proclamation at the request of Jain monks, Detail from Agra Vijnaptipatra, 1610. Opaque Watercolor and ink on paper, 284.7 x 32.2 cm. Ahmedabad: Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum (Acc.no.LDII.542 (Detail)). © Image: Courtesy of Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum.

RIGHT: Fig. 5. Unknown artist, Portrait of Ari Singh in a durbar overlooking the Manek chowk courtyard within his palace, based on contemporaneous Udaipur court paintings, Detail from Udaipur Vijnaptipatra, 1774. Opaque Watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 284.7 x 32.2 cm. Ahmedabad: Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum (Acc.no.LDII.Gol.85 (Detail)). © Image: Courtesy of Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum.

The emergence of new sovereignties, the rise of East India companies, and the expansion of pan-Indian mercantile networks contributed to the increased mobility of people and objects in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and possibly an explosion in the commissioning of elaborate painted letters. A vijnaptipatra was commissioned by Jain mercantile collectives who were keen to embed themselves in trans-regional religious networks and who closely tracked the changing political-mercantile landscape of their city.[19] Scroll painters, for their part, took a special interest in picturing emergent power brokers and contemporary events. The Agra vijnaptipatra (1610) depicts the Mughal emperor Jahangir’s proclamation (farmana) – issued at the request of important Jain monks – which sought to forbid the killing of animals during a period of twelve holy days on the Jain calendar (paryushana).[20] The painter Salivahan emphasized this historicity by portraying and labeling the presence of diverse important figures from Jain merchants to Jain monks, Mughal imperial officers and European ambassadors in the court and city of Agra. Most scrolls from Surat and the Cambay area, for instance, depict a ship with the Union Jack flag and a fortified port town, suggesting the presence of British merchants and rulers. Another late nineteenth-century scroll of Jodhpur emphatically shows the domain of the influential religious sect of the Nath yogis and Jallandarnath alongside the Jains, and yet another example depicting Diu in Saurashtra in 1666 includes a vignette of Dutch merchants, signaling their recent settlement in this port city.[21] Such scrolls demonstrate that several merchants of the local Jain community played key roles as negotiators and financiers within the circles of the Mughals, regional kings of Northern and Western India, and the various East India trading companies.

Fig. 6. Salivahan, Receipt of the scroll by Jain Pontiff Vijaysena Suri, Detail from Agra Vijnaptipatra, 1610. Opaque Watercolor and ink on paper, 284.7 x 32.2 cm. Ahmedabad: Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum (Acc.no.LDII.542 (Detail)). © Image: Courtesy of Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum.

This integral connection of a vijnpatipatra to the mercantile space of the bazaar, the mixing of pictorial tropes and images from distinct genres, and the layering of ontological functions, enables us to consider painted invitation scrolls as multilayered bazaar objects. Indeed, several painted letters like the Sirohi scroll (1761) depict a merchant handing over a dated scroll to a messenger, which suggests an artistic consciousness of a painted invitation letter’s connectedness to early modern bazaars. In picturing a vignette of the market populated by Jain merchants as the instrumental space through which the scroll circulates – between where the farmana was issued (at the Mughal court) and the site of its receipt (the Jain monk’s durbar) – the painter Salivahana expands the imaginary of the city of Agra beyond the Mughal court to the world of commerce, from where the Jains claimed their power and connection to both the city and the Mughals (Fig. 6). Writing about late nineteenth- and twentieth-century Indian calendars as “bazaar images,” Kajri Jain argues that calendar art alludes to the character of the bazaar as a space where domains of commerce, religiosity, and polities intersected, and where its makers formulated their vernacular pictures in characteristically hybrid ways that simply could not belong to a singular domain.[22] It is this multilayered character of bazaar objects that I find particularly productive for understanding vijnaptipatra as one possible kind of bazaar object – constituting functions from an urban panegyric scroll to a cartographic object, from an invitation letter to a proclamation document – that traversed early modern and colonial India. They can be interpreted only at the borders or interstices of various registers.[23] They could (and can) assume different roles based on who is viewing, reading, or receiving them. They cannot be categorized or fixed.

The prospect of wide-ranging audiences, the collective patronage and annual circulation of several invitations, and the experimentation of pictorial conventions and forms from courtly and sectarian contexts in the painted letter itself, equally provides the basis for my understanding of a vijnaptipatra as an object that forged an important vernacular domain in the material culture of South Asia. We know that a diverse and large community of monks, nuns, and lay people traveled together on Jain pilgrimages to holy centers as well as during the annual establishments of itinerant religious centers in cities from which invitations were issued.[24] In almost all scrolls we see groups of monks, men, and women attending assemblies held by Jain monks, as in the case of the 1830 Udaipur vijnaptipatra as well (Fig. 7).[25] It is quite possible that this community or several of its prominent mercantile members, apart from the invited monk, were able to see and interpret this idealized pictorial image of Udaipur’s bustling bazaars.[26] Certainly the domain of the “popular” that a vijnaptipatra created was still quite limited and distinct in terms of the elite constituency of its mercantile patrons, production technology, and the number of scrolls when compared to the mass appeal of chromolithographed calendars from the following century. Nonetheless, because the scrolls circulated within larger non-courtly audiences, they offer us grounds to think about the creation and reception of art and history, the formation of aesthetic sensibilities, and the forging of popular memories among a broader spectrum of people.

While it is nearly impossible to discuss the plethora of sites and people in this 72-foot long 1830 scroll, for the purposes of this essay I briefly examine below the idioms and styles of Udaipur court painting that were employed to praise the city pictorially to prospective visitors. In the following sections, I draw greater attention to the view from the bazaars of Udaipur and how artists and scribes presented their subjective interpretations of urban change. It is very possible that such scrolls were created in a painting workshop in the bazaar where a city’s artists, knowledgeable of a canon of court paintings, contributed to different aspects, such as drawing the outlines, coloring the composition, and writing the labels. However, since I have been unable to attest with any degree of certainty to this kind of group collaborative effort in the making of the 1830 Udaipur vijnaptipatra, I shall for now refer to the artist of this scroll as a single entity. The 1830 scroll has been made by pasting together sheets of paper two feet in length.[27] The corpus of painted vijnaptipatra, ranging from 15 to 72 feet in length, present as much of a visual and analytical quandary for the art historian today as they might have presented for the artists who visualized these long compositions and for the historical audiences who viewed them. Whether monks unrolled the complete scroll on the floor for its primary audience – Jain pontiffs to whom the invitations were addressed – or if the pontiffs held the scroll themselves, it is only possible to see in a focused manner up to two or three feet of the scroll at a time. Any viewing, then, is partial.

Citing Courtly Udaipur for Constituting a Charismatic Place

The artist of the 1830 Udaipur vijnaptipatra eulogized Udaipur as an ideal place, specifically by alluding to courtly interest in combining portraiture with place-making in Udaipur court paintings. The artist’s portrayals of the current ruler Jawan Singh in a series of royal activities cites the picturing of Udaipur rulers in a temporal sequence within large-scale paintings. Jawan Singh is shown, for example, enjoying a boat procession with his nobles (Fig. 8); dining, privately, within the inner palatial domains (Fig. 9); performing rituals, bare-chested, at the court-temple (Fig. 9a); and presiding, as a public figure, along with his sixteen nobles as an embodiment of the state within the courtly space of the large-assembly hall (Fig. 10). The artist’s careful selection of vignettes sought to convey the distinctive facets of idealized kingship in action at the Udaipur court.[28]

LEFT: Fig. 9. Jawan Singh dinning privately in the dinning hall adjacent to the palace kitchen courtyard. Detail of Fig. 1.

CENTER: Fig. 9a. Jawan Singh performing rituals at the court-temple. Detail of Fig. 9.

RIGHT: Fig. 9b. Planimetric view of the women’s palace. Detail of Fig. 9.

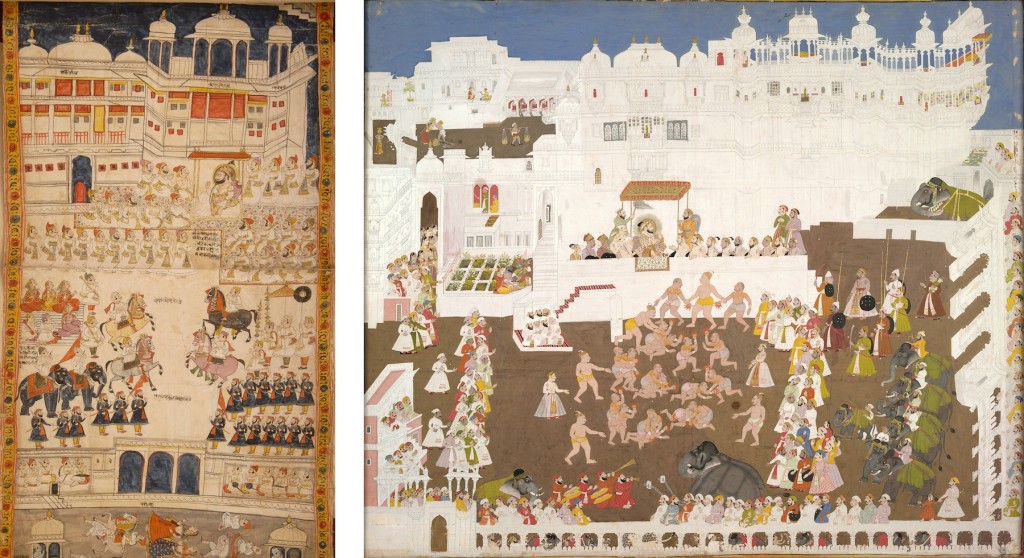

LEFT: Fig. 10. Jawan Singh with his sixteen nobles in a durbar held at the large-assembly hall (bada darikhana) in the palace. Detail of Fig. 1.

RIGHT: Fig. 11. Unknown artist, Maharana Sangram Singh II and Durga Das Rathore of Jodhpur watching Jethi wrestlers at Manek Chowk, 1716-18. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 82 x 94 cm. Udaipur: City Palace Museum (Accession No. 2012.19.0028) © Image: Courtesy of Museum Archives of the Maharanas of Mewar, MMCF, Udaipur.

It is, however, in the detailed depiction of palace environs that the scroll’s artist reveals the breadth with which he adapts pictorial conventions of constructing royal portraits and praise. By depicting the well-established iconic façade of the Udaipur palace, the artist has transposed a signature architectural feature of horizontally-oriented court paintings onto the narrow, vertical format of the scroll (Fig. 11). The artist lent further force to his citations by drawing outlines to color the deep blue of the sky, which allowed him, like court artists, to highlight the profiles, twists, and turns of domed and angular roofs. While Udaipur’s court artists emphasized a visual sense of continuity in the palace façades when seen from the Manek chowk courtyard, the scroll’s artist has pictorially disaggregated this view (Fig. 12). The artist has ingeniously divided the horizontal palatial façade based on how the individual courtyard buildings were spatially laid out within the complex. At the same time, he has established continuity within this segmented façade by employing a palette of red and yellow hues with black outlines and by writing inscriptions that identified various gateways and courtyards. It is equally possible that the artist employed this format based on circulating mapping practices, especially for spaces that were not associated with an established iconography in court painting. For example, in representing the women’s palace of Udaipur, which has been pictured in a very limited number of court paintings, the artist chose to depict a plan view, which can be related to an eighteenth-century architectural drawing of the city’s palace complex (Fig. 9b).[29] In addition to displaying his aptitude for making stylistic and convention-based choices, especially in his picturing of temples devoted to multiple deities, mosques, and Sufi shrines along the central street of the bazaars, several such instances attest to the artist’s interest in conveying his knowledge and spatial perception of the buildings he observed. Moreover, the artist’s prolific labeling of precincts conspicuously revealed his penchant for mapping Udaipur, such that the painted invitation letter must be read as an epistemic genre that contains and expresses the artist’s cartographic vision.

Expanding Artistic and Historical Views of and from the Bazaars

In presenting a picture of courtly praise and cartographic knowledge as a means to constitute Udaipur as a charismatic city, the artist of the 1830 Udaipur vijnaptipatra also sought to expand his view of mercantile space and urban ethnography (Fig. 13). He departed from the typical metaphorical reference to a bazaar populated with men and women within a vijnaptipatra, as seen in the above-discussed Sirohi scroll, by reinforcing the specificity of each trade and individual. The local Udaipur artist depicted the bustling mercantile and urban space of the city and prolifically labeled different spatial clusters of the bazaar: the areas occupied by dyers, barbers, arms makers, utensil sellers, cloth sellers, flower sellers, and moneylenders (Fig. 13a and 13b). He highlighted the acts of making and selling, and delineated each individual’s turban and facial features. This personalization, visible even in the smallest detail of the men’s beards, perhaps suggests the relation between certain trades and specific communities.

LEFT: Fig. 13. Several kinds of shops and trades in the city-bazaar. Detail of Fig. 1.

CENTER: Fig. 13a. Cluster of cloth sellers shops. Detail of Fig. 13.

RIGHT: Fig. 13b. Utensil-sellers and a barber shop. Detail of Fig. 13.

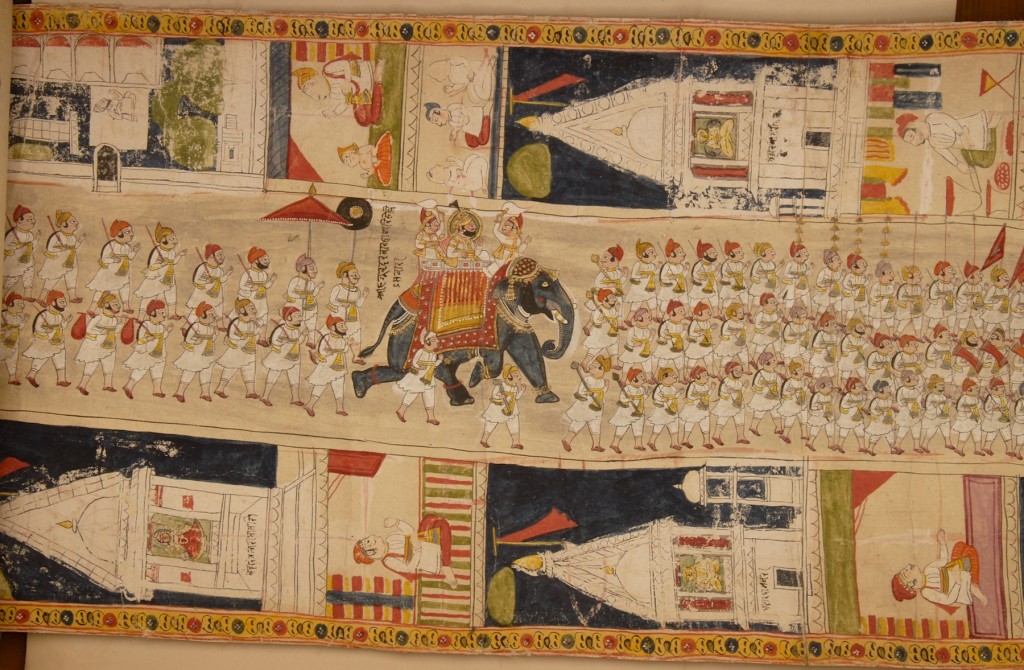

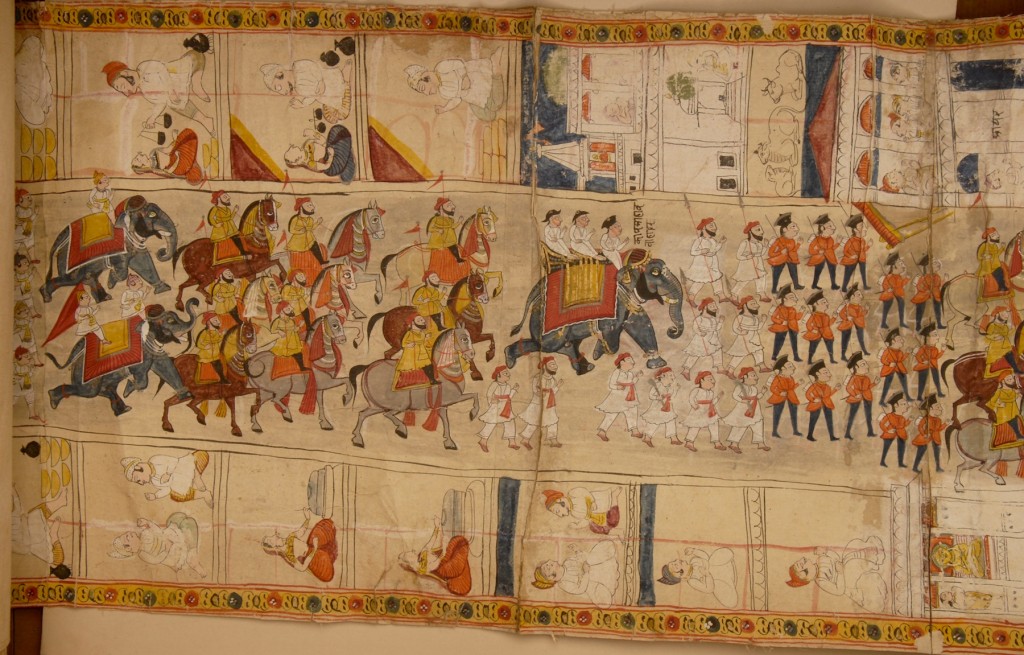

The scroll artist further transformed the central street by embedding horizontally-painted processions from court painting within the vertical idiom of the vijnaptipatra, creating a perplexing dual axis along which one could view the scroll. He depicted a long retinue of footmen, horses, elephants, and troops, culminating in a portrayal of the ruler Jawan Singh mounted on an elephant (Fig. 14). Further along the street, he painted another elephant with three British officers. Udaipur’s current political agent, Alexander Cobbe, is shown accompanied by sepoys and Skinner’s cavalry from the British Indian army (Fig. 15).[30] Here the artist drew upon the symbolic currency of the aesthetic trope of processions that Udaipur court artists employed in this time period to construct royal portraits and commemorate practiced routine processions. Court artists experimented with multiple scales and, in some instances, miniaturized the chorography of Udaipur’s environs, while in others the procession itself was miniaturized. It is important here to reiterate the uniqueness of this visualization of Udaipur – for processional and mercantile spaces to be combined and given equal weight was unprecedented in court painting and in vijnaptipatra.[31] An earlier example of a manuscript leaf from the Jagat Singh Ramayana, the Ayodhyakhanda completed in 1640 and attributed to the style of the Mewar master artist Sahibdin, depicts merchants decorating their shops with fine textiles and brocades and people sitting on roofs of their houses and on temples, to secure the best view of the anticipated procession for the consecration ceremony of Rama (Fig. 16).[32] The Udaipur artist has, however, situated the bazaar street amidst temples – as seen in a vijnaptipatra – specifying the presence of a Jain temple by representing an icon of a Jina. The scroll artist’s juxtaposition of pictorial conventions extends the semantic content of the visual trope of processions.[33] He locates the procession within the streets of Udaipur, as if the artist sought to illuminate the mercantile space – within which the procession was performed and upon which it relied – rather than presenting a chorography of Udaipur’s palaces as a panegyrical backdrop for royal patrons.

Fig. 16. Sahibdin, Bazaar Street in Ayodhya, Ayodhyakhanda of the Jagat Singh Ramayana, 1650. Opaque watercolor on paper, 23.0 x 39.9 cm. London: The British Library (Add.MS 15296 (1),f.16a) © Image: Courtesy of The British Library Board.

Vijnaptipatra as Critical Pictures of Travels and Territoriality

While we can infer that the artist painted the scroll in the sequence I have discussed above, it is important to consider that the recipient, Jinharsh Suri, who then resided in Bikaner, must have unrolled the scroll to first read the vijnapti or invitation letter (Fig. 17).[34] The attached letter employs poetic renditions in Sanskrit as well as regional dialects of Gujarati and Rajasthani, like most eighteenth- and nineteenth-century letters within vijnaptipatra that combined verse and prose, to eulogize the invited monk.[35] Pandits Rukhabdas and Khushalchand have cited several standard laudatory epithets for the invitee in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Gujarati, and it may be possible to trace some of these to the letters within other vijnaptipatra, including the Agra vijnaptipatra (1610).[36] The citation of previous letters allowed the scribes to exhibit their knowledge of other invitation letters and to embed the current letter within the established tradition. They also referred to towns that were already located within pilgrimage networks through the circulation of letters.

Having created this pastiche of laudatory texts, the scribes of this Udaipur vijnaptipatra shift to writing in the local Rajasthani dialects of Mewari and Marwari, in order to convey the specificities pertaining to the current invitation. The letter explicitly links the monk’s arrival with prosperity (labha) and good reputation (mahima) for the entire “Mewar country.” The scribes further elaborate that the monk’s arrival will be advantageous for agricultural production, benefit the beautiful people [of the place], bring fame to the administration, and ultimately propagate goodwill (kalyana) in all spheres (sarva bata).[37] They offer their sincere and humble homage to Shri Jinharsh Suri on behalf of the entire community (sangha) of Udaipur, and emphasize that “very big (mota mota),” implying rich and famous, merchants await his arrival in this city, in the hopes that the tributes would be accepted.

LEFT: Fig. 17. Scribes Pandit Rukhabdas and Khusalchand, Beginning of the textual letter. Detail of Fig. 1.

RIGHT: Fig. 18. Troops and palanquins next to the British residency and the assembly of Jain Pontiff Jinharsh Suri. Detail of Fig. 1.

These verses echo the scroll artist’s careful pictorial, if aspirational, imagining of the arrived monk, a time that is yet to come. The visualization of the invited Jain monk’s assembly, as highlighted in the introduction to this essay, implies the artist’s hope that the Udaipur vijnaptipatra (1830) would be effective, its objective realized by the monk’s arrival in the city. A group of elites, palanquins, and troops are depicted waiting upon both the monk’s durbar and the British residency depicted on the opposite side of the central street (Fig. 18). The artist has pictured the British residency, labeled as the “Sahab’s Bungalow” and the “cantonment of the foreigner (firangi).” Captain Alexander Cobbe had acquired this courtyard house in 1824 from one of Udaipur’s prominent chieftains, and expanded the building into his residence. While the depiction of Jain monks holding assemblies is common in other scrolls of this genre, here, in imagining this anticipated religious assembly precisely opposite the residency, and by pictorially matching its scale, the artist has presented the colonial and religious powers as two equal and competing domains of authority. Likewise here the depicted procession of the Udaipur ruler and British agent can be interpreted as proceeding towards the anticipated Jain monk’s assembly. Such gestures imbued the scroll with multiple temporalities, suggesting that the charismatic landscape of Udaipur would become an “ideal” place only after the invited Jain monk’s domain was established.

The anxiety reflected in the transmission details of the scroll suggests the strategic role of this Udaipur vijnaptipatra. Towards the end of the letter and before we see the signatures of Udaipur’s merchants, the scribes recorded an apology for the delay in sending the “painted letter (chitralekha).” They explain that the prominent Udaipur merchant Seth Joravarmalji Bapna was away and Shersingh Mehta, his secretary (munshi), was also on leave, noting that the painted letter was thus being sent through the Udaipur ruler’s messenger (harkara). In explaining this delay, the scribes note how the arrival of the Maharaja (that is, the Jain monk Jinharsh Suri) would help many people to “emerge” (udai hosi) from a plethora of problems. It is likely that such phrases may have enabled the scribes to write their invitation requests by employing a variety of standard phrases similar to the tropological phrase that implied “you may please arrive early and do not delay your trip (apa kripa karke vega padarsi dila karavsi nahina),” which is repeated through the letter and in the merchants’ signatures.

However, in light of the possible relationship of this vijnaptipatra to a wider network of diplomatic letters that were circulating between the Udaipur court and British officers at this time, the scribes may also be suggesting the urgency of issues that were facing the city. Already by 1818, the British colonial agent James Tod wrote about the lack of mercantile fervor in Udaipur. The years from 1823 onwards were particularly stressful for the Udaipur ruler Bhim Singh and even more so for his successor, Jawan Singh, both of whom had to negotiate their own positions and financial needs vis-à-vis the British East India Company and regional merchants. Yet Tod’s successor, Colonial Agent Cobbe, who is depicted in the painted procession, was highly critical of his predecessor’s policies. By Oct 14, 1830, he ensured that the Udaipur Agency as well as the Jaipur Agency were abolished.[38] This abolition not only had implications for the political status of Udaipur as a princely state under indirect British rule, but also implied that the Udaipur rulers would not be able to negotiate their rights and allowances directly with an exclusive British Political Agent residing in Udaipur.[39] The Udaipur ruler Jawan Singh immediately sent a letter to Cobbe stating that he was “hurt” by this treatment. It appears, therefore, that this Udaipur vijnaptipatra was sent exactly around the same time in 1830 with the diplomatic aim of propping up another sphere of authority in the city.

Jain merchant communities who collectively commissioned such painted invitation letters not only effectively displayed their religious piety and inserted their towns into a pilgrimage economy but also reinforced their political and economic authority in the wake of British colonization. Likewise many Jain scribes, mid-level bureaucrats, and pundits played a key role in crafting royal authority and intellectual practices at the Mughal centers and regional courts.[40] Both Joravalmal Bapna and Sher Singh Mehta belonged to the Osval Jain community, who were particularly valued for their business, administrative, and religious networks in Udaipur. By the 1830s, Sher Singh’s family had been working at the Udaipur court as bureaucrats for many generations. Joravarmal Bapna had considerable political influence in cities across Northern India from Udaipur, Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Bikaner to Indore. He was especially helpful in assisting Tod in negotiating with the princely state of Indore, so that when Tod came to Udaipur, he took it upon himself to revive the city’s mercantile activity by sending his own letters inviting merchants of repute, including Joravalmal Bapna. Jain vijnaptipatra scrolls were thus equally embedded in contemporaneous diplomatic correspondence between the British officers and the Udaipur court. The local artist of the 1830 Udaipur scroll extolled a charismatic landscape inhabited by prosperous urbanites and powerful groups, and projected a cosmopolitan and contiguous Jain landscape in relation to other religious, political and mercantile domains throughout the length of the scroll. The remarkable multivalent character of these scrolls provides an avenue by which we can examine the way nineteenth-century religious movements and establishments crossed the boundaries between British and princely India, a field of inquiry that requires more research.[41]

Multilayered Material Memories

The Udaipur vijnaptipatra of 1830 is, therefore, simultaneously a grand representation of an ideal city, a topographical map, a picture of overlapping and relational identities, and an epistle embedded in shifting territorial claims during the long eighteenth century. Artists and scribes also created a material object that traveled from a place and embodied in various ways its connection to the represented city, thereby possessing the power to arouse feelings that could entice its receivers to undertake travels. By transforming the assumed relationship of how audiences might see and perceive the scroll, the artist sets interpretive processes into motion. Monks probably unrolled the unwieldy 72-foot-long scroll two or three feet at a time. As viewers slowly traversed the city of Udaipur, images of the densely populated procession attracted their gazes and continually disrupted their progress through the scroll. This would have necessitated contemporary audiences to view and re-view the scroll closely. Its materiality literally forced audiences to see the idealized domain of the palaces at the end only after they had seen multiple, interrelated domains of religiosity, commerce, and authority. The very structure of the painted invitation letter precluded engaging with the whole picture, whether as a large-scale long topographical panorama, a processional painting, a bounded cartographic map, an architectural drawing, or a picturesque view. Rather, it constituted several pictures that stacked up in the mind’s eye as one unrolled it, as if to replicate traveling or walking through the city of Udaipur.

The act of unfurling the scroll simulates an act of entering into the city from its outskirts. The cultural historian Michel de Certeau has critiqued the ways we pay greater attention to the represented city that has been visualized in tautological terms by artists, mapmakers, architects, and planners.[42] De Certeau instead proposes that we turn to spatial practices like walking, which are performed in a city at the ground level, to consider what this act does for the formulation of the imaginary, remembered, and subjective cartography of a place. The practice of walking constitutes a particular kind of practice of everyday life that has the power to communicate plural geographies of a city, including the weaving of memories of being in-the-place. The Udaipur vijnaptipatra (1830) was not a route map that directed its users to turn right or left on a street and follow a particular route to reach Udaipur, nor did its artist seek to represent a measured drawing of the city’s precincts. The scroll’s artist has cited the picturing of Udaipur’s palaces and processions from court commissions in meaningful ways, while simultaneously transforming the represented street from a metaphorical pictorial element that signaled a thriving city, as seen in earlier painted letters, to one that evokes a sense that the artist is marking the street with specificities. It recalls a sense of being in the place. The Udaipur vijnaptipatra (1830) must be recognized as a bazaar object that formulates a vernacular mapping practice – not only because of the translated images and mixing of pictorial tropes that we see in this scroll but also because of the senses of the street, of the everyday, of a plethora of spatial and political stories that one encounters in it.

The Udaipur vijnaptipatra in terms of its form and content presents an opportunity to rethink how makers and audiences in nineteenth-century India conceived of maps and mapping from vantage points quite different not only from those of British colonial agents like Tod and Cobbe, but also detached from the gaze of regional rulers like Bhim Singh and Jawan Singh. This scroll exemplifies how alternate regional imaginings of place-making – in the midst of emergent visual practices, bazaars, regional polities, religious institutions, and empires in the early nineteenth century – were redefined and embedded in circulating painted invitation letters. The continuous disruptions signaled by the scroll’s format evoke the challenges of imagining a city in flux that the 1830 invitation letter presents. The visual and analytical quandary of negotiating the pictorial idioms, axes, and double movement parallels how historical viewers and artists negotiated multiple institutions and polities. At the same time, we may read the dynamic corporeal relationship that the scroll establishes as a metaphor for the constantly shifting relationship the art historian has to the historical object.

Dipti Khera is assistant professor in the Department of Art History and Institute of Fine Arts at New York University

Acknowledgements: I thank Noémie Etienne and Meredith Martin for the opportunity to present in the panel “Pilgrim Arts of the Eighteenth Century (Historians of Eighteenth-Century Art and Architecture)” at the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Annual Conference, 2015, and for their insightful comments on the revised version of this paper. I am also grateful to Hannah Williams and the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback and comments. I thank the Forum Transregionale Studien, Berlin, where I am a 2015/16 Art Histories and Aesthetic Practices Fellow, for their support. For the convenience of the broader audience, I have eliminated the use of diacritical marks.

[1] Vijnaptipatra were largely sent by Shvetambara Jains, who owe religious alliances to “white-clad” ascetics, in comparison to the other Jain sect Digambara, who follow “sky-clad,” or naked, ascetics. On epistolary aspects of letters, see Hirananda Śastri, Ancient Vijñaptipatras (Baroda: Baroda State Press, 1942).

[2] The Udaipur vijnaptipatra (1830) belongs to the private archive of the Nahata family, which was one of the most important mercantile families in nineteenth-century Bikaner. I thank Mr. and Mrs. Vijaychand Nahata and the Librarian Mr. Chopra for enabling access, and Jonas Spinoy for his photographs of the scroll.

[3] For a discussion of James Tod’s Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan (published originally by Smith Elder in 1829 and 1832), and how his writings have significantly shaped the discussion on Rajasthan as the “land of kings,” see Jason Freitag, Serving Empire, Serving Nation: James Tod and the Rajputs of Rajasthan (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2009).

[4] Igor Kopytoff, “The Cultural Biography of Things,” in The Social Life of Things, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 64–91.

[5] Chanchal Dadlani, “The ‘Palais Indiens’ Collection of 1774: Representing Mughal Architecture in Late Eighteenth-Century India,” in Globalizing Cultures: Art and Mobility in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Nebahat Avcıoğlu and Finbarr Barry Flood (Ann Arbor; Washington, D.C.: Dept. of the History of Art, University of Michigan; Freer Gallery of Art, 2010), 175–197; William Dalrymple and Yuthika Sharma, eds., Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707-1857 (New York; New Haven: Asia Society Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2012); Holly Shaffer and Yale Center for British Art, eds., Adapting the Eye: An Archive of the British in India: October 11-December 31, 2011 (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 2011).

[6] Michael Herbert Fisher, Indirect Rule in India: Residents and the Residency System, 1764-1858 (Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

[7] Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

[8] Sanjay Subrahmanyam, “Connected Histories: Notes Towards a Reconfiguration of Early Modern Eurasia,” Modern Asian Studies 31, no. 3 (July 1, 1997): 735–762. For a discussion of objects as the real “globetrotters” in the early modern world, including a bibliography of the rapidly expanding scholarship in this area, see essays and introduction in the recent volume edited by Meredith Martin and Daniela Bleichmar, “Objects in Motion in the Early Modern World,” Art History 38, no. 4 (September 2015).

[9] Claude Markovits, Jacques Pouchepadass, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam, “Introduction,” in Society and Circulation: Mobile People and Itinerant Cultures in South Asia, 1750-1950, ed. Claude Markovits, Jacques Pouchepasdass, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam (Delhi; Bangalore: Permanent Black; Distributed by Orient Longman, 2003), 8.

[10] Sheldon Pollock, “Is There an Indian Intellectual History? Introduction to ‘Theory and Method in Indian Intellectual History,’” Journal of Indian Philosophy 36, no. 5–6 (October 1, 2008), 536.

[11] Nebahat Avcıoğlu and Finbarr Barry Flood, “Introduction,” in Globalizing Cultures, ed. Flood and Avcıoğlu, 7–38; Raziuddin Aquil and Partha Chatterjee, “Introduction,” in History in the Vernacular, ed. Raziuddin Aquil and Partha Chatterjee (Ranikhet; Bangalore: Permanent Black; Distributed by Orient Longman, 2008), 1–24.

[12] In recent years, scholars have turned to regional language sources from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries to explore how historical memory was embedded in literary genres. For example, see Allison Busch, “Hidden in Plain View: Brajbhasha Poets at the Mughal Court,” Modern Asian Studies 44, no. 02 (2010): 267–309; Kumkum Chatterjee, “Communities, Kings and Chronicles The Kulagranthas of Bengal,” Studies in History 21, no. 2 (September 1, 2005): 173–213; Prachi Deshpande, Creative Pasts: Historical Memory and Identity in Western India, 1700-1960, Cultures of History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007). For a discussion on genres and theories of history created by Jain intellectuals, see John E. Cort, “Genres of Jain History,” Journal of Indian Philosophy 23, no. 4 (1995): 469–506.

[13] Quintessential narratives of eighteenth-century decline and the urgent need of British protection for mobilizing progress, like those of Tod, have been consistently challenged in the scholarly focus on the eighteenth century. See essays in Society and Circulation, eds. Markovits, Pouchepadass, and Subrahmanyam.

[14] For lists of vijnaptipatras largely spread across several private libraries associated with Jain religious institutions in India, see Śastri, Ancient Vijñaptipatras; Nalini Balbir, Catalogue of the Jain Manuscripts of the British Library Including the Holdings of the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum (London: British Library & Institute of Jainology, 2006); S. K. Andhare, “Jain Monumental Painting,” in The Peaceful Liberators: Jain Art from India, ed. Pratapaditya Pal (New York; Los Angeles: Thames and Hudson, 1994), 76–87; Umakant Premanand Shah, More Documents of Jaina Paintings and Gujarati Paintings of Sixteenth and Later Centuries, 1st ed (Ahmedabad: L.D. Institute of Indology, 1976); Moti Chandra and Umakant Premanand Shah, New Documents of Jaina Painting, 1st ed (Bombay: Shri Mahavira Jaina Vidyalaya, 1975); Umakant Premanand Shah, ed., Treasures of Jaina Bhaṇḍāras, 1st ed, L.D. Series 69 (Ahmedabad: L.D. Institute of Indology, 1978); S. K Andhare and Laksmanabhai Bhojak, Jain Vastrapatas: Jain Paintings on Cloth and Paper (Ahmedabad: LalBhai Dalpatbhai Institute of Indology, Bhulabhai and Dhirajlal Desai Memorial Trust, Sheth Dalpatbhai Maganbhai (Hutheesing), Shardabhuvan Jain Pathshala Trust, Distributors, Variety Book Depot, New Delhi, 2015), 134–153.

[15] Pramod Chandra, “Ustād Sālivāhana and the Development of Popular Mughal Style,” Lalitkalā 8 (1960): 27–46.

[16] The Udaipur vijnaptipatra (1742, dimensions unknown) belongs to the Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad. The local Udaipur artist depicts the ruler Jagat Singh within a series of courtly settings, including a spectacle of animal fights, Udaipur’s palaces and lake Pichola, bazaars, and an assembly held by Jain monks. The local artist of an Udaipur vijnaptipatra (1774) also carefully cites vignettes and a connection to the artistic style from Udaipur court painting; however, he does not seek to represent either the Udaipur ruler Ari Singh’s portrait multiple times in relation to the various facets of his kingship or to connect him to the diverse courtly spaces in his palace. I thank Jayshree Lalbhai, Dr Ratan Parimoo, and the staff of Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum for enabling a study of an Udaipur vijnaptipatra (1774) in their collection, and Mark Ramussen for access to the Udaipur vijnaptipatra (1795) before the Bonham’s sale of Indian, South Asian and Himalayan Art in September 2015. A lengthier study of all these scrolls will be published separately.

[17] Udaipur’s court painters shifted to larger-scale portrayals of courtly settings during the early eighteenth century. For a discussion on such affective place-centric visions, see Dipti Khera, “Picturing India’s ‘Land of Kings’ Between the Mughal and British Empires: Topographical Imaginings of Udaipur and Its Environs” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University, 2013).

[18] Orsini has shown how concurrent “minor traditions” can be very useful for studying how broader audiences acquired their literary tastes in early modern India. See Francesca Orsini, Before the Divide: Hindi and Urdu Literary Culture (New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan, 2010), 11.

[19] Pilgrimages, especially to newly built temples in the context of nineteenth-century Shatrunjaya, coincided with a similar rise in fortunes of the Jain mercantile community in Bombay and Ahmedabad. See Hawon Ku, “Representations of Ownership: The Nineteenth-Century Painted Maps of Shatrunjaya, Gujarat,” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies (January 15, 2014), 1–19.

[20] Jahangir issued the farmana at the request of many important Jain monks. There was a longer history of Mughal emperors engaging with other prominent Jain monks who obtained various petitions related to forbidding animal slaughter in cities where Jains lived. Chandra, “Ustād Sālivāhana and the Development of Popular Mughal Style,” 27. See also Ellison B. Findley, “Jahangir’s Vow of Non-Violence,” Journal of American Oriental Society 107, no. 2 (June 1987): 245–256.

[21] Amit Ambalal, “A Vijnaptipatra Dated 1666 From Diu,” in The Ananda-Vana of Indian Art: Dr. Anand Krishna Felicitation Volume, ed. Navala Kr̥shṇa and Manu Krishna (Varanasi: Indica Books; Abhidha Prakashan, 2004), 312–318.

[22] Kajri Jain, Gods in the Bazaar: The Economies of Indian Calendar Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 15–16.

[23] Vijnaptipatra may also connect with the category of “border” or “frontier” or “boundary” objects that many scholars see as performing multiple ontological functions across social and political domains and across disciplines within a museum setting, each role brought into play based on distinct viewers and consumers. See Patricia Spyer, ed., Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces (London: Routledge, 1998); Star, S. L., and J. R. Griesemer, “Institutional Ecology, `Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39,” Social Studies of Science 19, no. 3 (August 1, 1989): 387–420.

[24] P. E Granoff and Koichi Shinohara, eds., Pilgrims, Patrons, and Place: Localizing Sanctity in Asian Religions (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2003).

[25] For example, a community of people including figures of merchants, men and women, nuns, and musicians are painted to suggest the demographic of the broader public space adjacent to the Jain monk’s assembly and key audience who witnessed the receipt of Jahangir’s proclamation in the Agra vijnaptipatra (1610). See Fig. 9.

[26] It is difficult to ascertain that such a practice of showing the scroll (as in other communities) wherein the “art” object functioned as a “cultural” prop was followed in the case of Jain painted invitation letters. See Jyotindra Jain, Picture Showmen: Insights Into the Narrative Tradition in Indian Art (Mumbai: Marg Publications on behalf of National Centre for the Performing Arts, 1998); Pika Ghosh, “Unrolling a Narrative Scroll: Artistic Practice and Identity in Late-Nineteenth-Century Bengal,” The Journal of Asian Studies 62, no. 3 (2003): 835–871.

[27] The part from the 1830 scroll with the representation of the British Residency and the assembly of the invited Jain pontiff measures approximately two feet.

[28] For a discussion of how eighteenth-century Udaipur artists were simultaneously interested in new ways to depict rulers in settings and in courtly panegyrics that drove such paintings toward portraiture, yet kept them from being straightforward visual documents, see Molly Emma Aitken, The Intelligence of Tradition in Rajput Court Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 119–127.

[29] Gopal Narayan Bahura and Chandramani Singh, Catalogue of Historical Documents in Kapad-Dwara Jaipur, Maps and Plans (Jaipur: Jaipur Printers Pvt. Ltd., 1990), Cat no. 155.

[30] James Tod recruited soldiers from Colonel James Skinner’s cavalry, who were known as yellow boys due to the color of their uniforms, in his army, and Alexander Cobbe increased their numbers in the army that the British agents maintained at Udaipur. Vijay Kumar Vashishtha, Rajputana Agency, 1832-1858: A Study of British Relations with the States of Rajputana During the Period with Special Emphasis on the Role of Rajputana Agency (Jaipur: Aalekh, 1978), 20–22.

[31] For example, in Mewar’s genealogical scroll dated around 1730-40 (Victoria and Albert Museum, Accession No. 07964/1 (IS)), we see vignettes that hint at the visualization of market space. I am grateful to Qamar Adamjee for bringing to my attention a folio from the mid sixteenth-century Laur-Chanda manuscript of an Indo-Persian romance, which depicts a bazaar vignette in the vertical format of Jain scrolls. Another vertical pictorial vignette representing a bazaar scene is seen in the double page from Nusrati’s Gulshan-i-‘Ishq, attributed to a Deccani court artist in Hyderabad (1710). Linda York Leach, Paintings from India, Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, vol. 8 (London; New York: Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press, 1998), 244–247.

[32] Jeremiah P. Losty, The Ramayana: Love and Valour in India’s Great Epic: The Mewar Ramayana Manuscripts (London: British Library, 2008), 11.

[33] It recalls paintings by Jodhpur’s contemporaneous artists that combined conventions of devotional pictures, pilgrimage maps, and town plans in response to new theo-political alliances and new image-viewing modalities that reveal the “conceptual frameworks through which historical viewers interpreted court paintings.” See Debra Diamond, “The Cartography of Power: Mapping Genres in Jodhpur Painting,” in Arts of Mughal India: Studies in Honour of Robert Skelton, ed. Rosemary Crill, Andrew Topsfield, and Susan Stronge (London and Ahmedabad: Victoria & Albert Museum; Mapin Publications, 2004), 278–285.

[34] The location of the delivery address on this scroll and the damage to many other scrolls on the end of the letter suggests the direction in which vijnaptipatra were rolled.

[35] The letters were related to Sanskrit literary practices like older Jain epistolary writing on palm leaf manuscripts, and to the seventeenth- to eighteenth-century Sanskrit messenger poems (dutakavya) that referenced similar ideas of sending invitations and messages to people in different locales. See Śastri, Ancient Vijñaptipatras, 5–8; Satyavrat Sastri, “Critical Survey of Dutakavyas,” in Essays on Indology, 1st. ed. (Delhi: Meharchand Lachhmandass, 1963), 82–138. While we have Sanskrit treatises outlining the rules and tropes for writing and decorating letters as literary compositions, no prescriptive text for writing vijnaptipatra has been found, though it appears that a handbook must have existed.

[36] I thank Phyllis Granoff for helping me identify some of the introductory laudatory passages, where the scribes appear to be referring to parts of the introductory text in the Agra vijnaptipatra (1610). Phyllis Granoff, “Identified,” August 24, 2010.

[37] For details on this passage, see Khera, “Picturing India’s ‘Land of Kings’ Between the Mughal and British Empires,” 326–330. We know that Jinharsh Suri traveled to Mewar and Udaipur during his lifetime; however, there is no definite record indicating if his travels were undertaken after receiving the painted invitation letter discussed here. For an account of his travels, see Vinayasāgara and Prākr̥ta Bhāratī Akādamī, Kharataragaccha kā bṛihada itihsāsa (Jayapura: Prākr̥ta Bhāratī Akādamī, 2005), 246–247. I thank John Cort for sharing this reference.

[38] Political Correspondence, 14 October 1830, The National Archives, New Delhi. See also Political Correspondence, March-August 1831, which describes the termination of the letter writing offices at Udaipur and Jaipur. British Library, IOR/F/4/1384/44168.

[39] Vashishtha, Rajputana Agency, 1832-1858, 15–40.

[40] Recent explorations stress the importance of drawing Jain patrons and intellectuals into a larger conversation. Audrey Truschke, “Dangerous Debates: Jain Responses to Theological Challenges at the Mughal Court,” Modern Asian Studies 49, no. 5 (February 2015): 1–34.

[41] See Imre Bangha, “Courtly and Religious Communities as Centres of Literary Activity in Eighteenth-Century India: Anandghan’s Contacts with the Princely Court of Kishengarh-Rupnagar and with the Math of the Nimbarkar Smapraday in Salemabad,” in Indian Languages and Texts Through The Ages: Essays of Hungarian Indologists in Honour of Prof. Csaba Töttössy, ed. Csaba Dezsö (New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors, 2007), 307–354; Hugh B. Urban, “The Marketplace and the Temple: Economic Metaphors and Religious Meanings in the Folk Songs of Colonial Bengal,” The Journal of Asian Studies 60, no. 4 (2001): 1085–1114; Shandip Saha, “The Movement of Bhakti along a North-West Axis: Tracing the History of the Puṣṭimārg between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” International Journal of Hindu Studies 11, no. 3 (2007): 299–318.

[42] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 91–110.

Cite this article as: Dipti Khera, “Marginal, Mobile, Multilayered: Painted Invitation Letters as Bazaar Objects in Early Modern India,” Journal18, issue 1 (Spring 2016), https://www.journal18.org/527. DOI: 10.30610/1.2016.4

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.