In the 2018 music video Apesh*t (Fig. 1), Beyoncé Knowles Carter and her husband Jay-Z move us through the tourist thoroughfares of the Louvre, all while rapping about their meteoric rise to fame.[1] The chorus, “I can’t believe we made it/This is what we’re thankful for,” is coupled with verses detailing their material acquisitions: “Gimme my check, put some respek on my check/or pay me in equity/watch me reverse out of debt/He gotta bad bitch, bad bitch/We livin’ lavish, lavish/I got expensive fabrics/I got expensive habits.” Famous artworks, the Mona Lisa and Venus de Milo among them, become the backdrop to their narrative of black excellence.[2] Offering a plausible sequel to Beyoncé’s 2016 album Lemonade, which explored the nuances of marriage, infidelity, and black womanhood, Apsh*t presents the Carters as a united front, a paradigm for black love and success.[3]

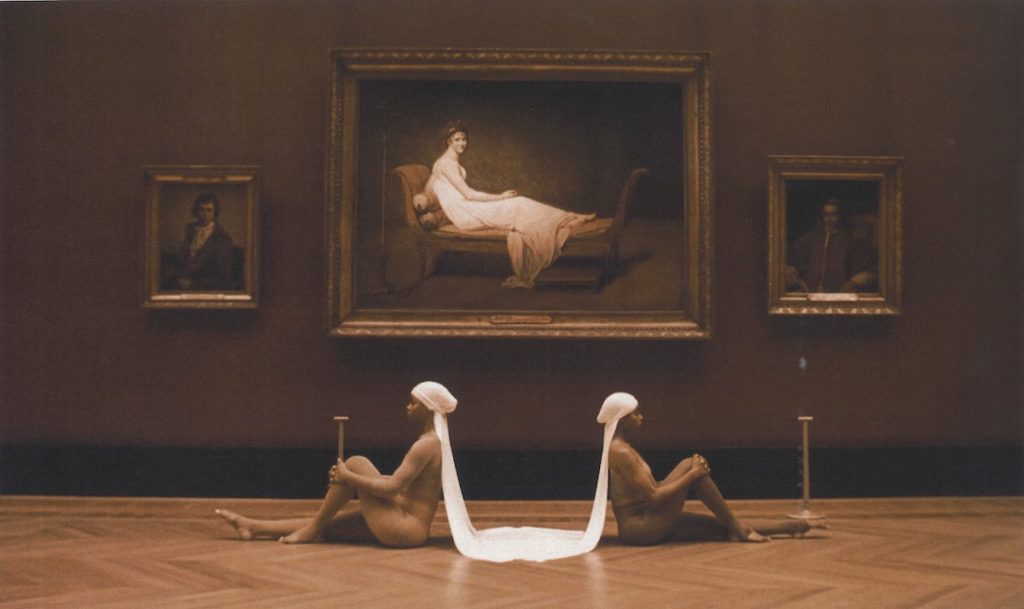

Doreen St. Félix, commenting in The New Yorker on the internet’s initial “think-piece” reactions to Apesh*t, writes, “either Beyoncé and Jay-Z are priests of capitalism who appreciate art only to the extent that it reflects their wealth, or they are radicals who have smuggled blackness into a space where it has traditionally been overlooked.”[4] Both interpretations, she argues, are too prescriptive and ignore the Carters’ artistic interest in staging tableaux.[5] “Beyoncé does not blot out the Venus de Milo,” according to St. Félix, “she dances next to it.”[6] The assertion that the Carters are not just participating in the art world as patrons or activists but as makers of tableaux vivants, or “living pictures,” is made quite literal in their staging of Jacques-Louis David’s Madame Récamier (1800) (Fig. 2). Madame Récamier appears only once at a critical break in the music midway through the video. Beyoncé and Jay-Z are absent; a low bell tolls as the camera zooms in slowly towards the painting (2:14; Fig. 3). Two seated women, facing away from each other, are joined by a shared white headscarf. Their linked bodies mirror the composition of Juliette Récamier’s half-seated, half-reclining form on a Neoclassical chaise lounge. There is no dancing, no music, just the quiet interplay between the seated figures and the painting.

The scene recalls the popular tableaux vivants of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in which aristocratic and bourgeois elites would pose in imitation of artworks or dramatic historical and literary scenes for personal entertainment. The practice emerged, in part, from the attitudes of Emma Hamilton, who mimetically acted out the poses of classical statuary for Grand Tourists, dignitaries, philosophers, and artists living and traveling in late eighteenth-century Naples. Taking on the trope of the “living statue,” Hamilton was engaging with a vibrant eighteenth-century discourse on the tactility of sculpture and the performance of white femininity as it related to the animation of white marble statuary.[7] By the nineteenth century, as both Mary Chapman and Jennifer Fisher have shown, the self-referential logic of the tableau vivant parlor game allowed participants to both imitate and appropriate the original artwork as a means of elevating their cultural and intellectual status.[8] An 1860 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine describes the practice as “one of the most innocent, entertaining, and instructive amusements for the young, engendering a love for and appreciation of art.”[9]

In Apesh*t, the Carters appropriate this self-referential parlor game as a visual analogy for their own success in a culture of systemic racism. While the dancers embody acts of imitation that bring our attention to the masterpieces of the Louvre, the dancers’ blackness—continually brought to the foreground through costume, choreography, and their sheer presence in such an institution—destabilizes the tableau vivant’s traditional mimetic relationship between actor and artwork. Their blackness hinders the ability to fully imitate due to the conspicuous absence of black and brown bodies throughout the “encyclopedic” museum. By politicizing the tableau vivant, the Carters’ staging of Madame Récamier is a critique of the omnipresent status of (white) marble in the European consciousness. Their performance underscores the dangerous neutralization of whiteness, propagated in particular by neoclassicism and its racial, colonial, and capitalist legacies.[10]

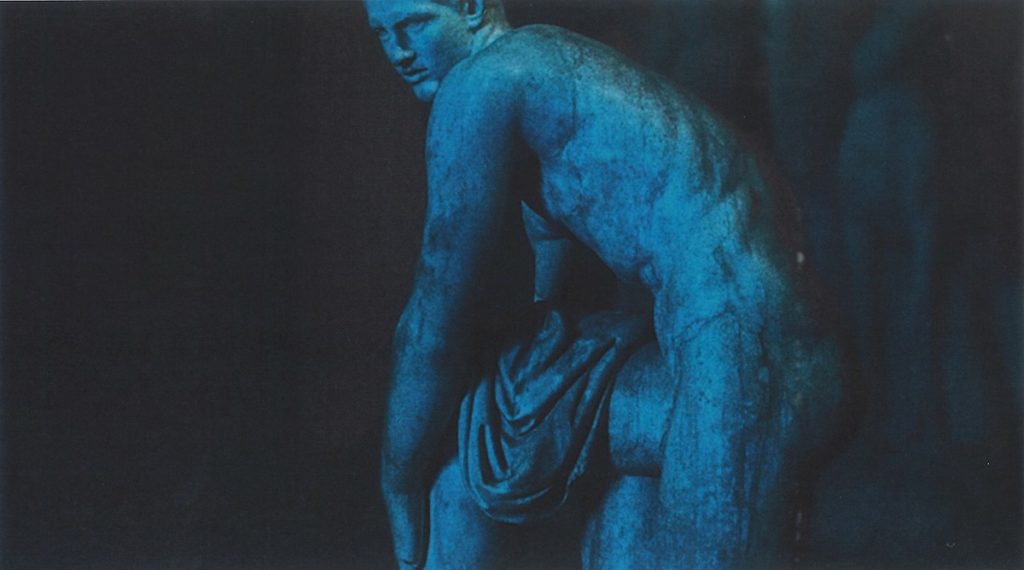

The portrayal of sculpture—or lack thereof—throughout Apesh*t’s six-minute run time is striking. Details from the vaults of Charles Le Brun’s Galerie d’Apollon (0:27) and Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (3:05), among other paintings, fill frame after frame; the visible brushstrokes testifying to the materiality of pigments and dyes. In contrast, the camera refuses to give sculpture such sustained material attention. In lingering shots of the Venus de Milo (3:57) and Hermes Fastening His Sandal (3:34; Fig. 4), the marble is shrouded in a glowing blue light that obscures its whiteness—perhaps a tacit acknowledgement that the white marble of antiquity is one of the enduring lies of art history.[11] A chorus of dancers atop plinths are similarly veiled in blue (1:04). In a reversal of Ovid’s Pygmalion myth where Galatea is transformed from white marble to flesh, the dancers’ bodies—backlit so that they appear as abstracted silhouettes—become statues.[12] Later, the Carters, dancing in front of the Great Sphinx of Tannis doused in a red light (1:20), reclaim the art of ancient Egypt from its proscribed role as the predecessor to the achievements of ancient Greece and Rome.[13]

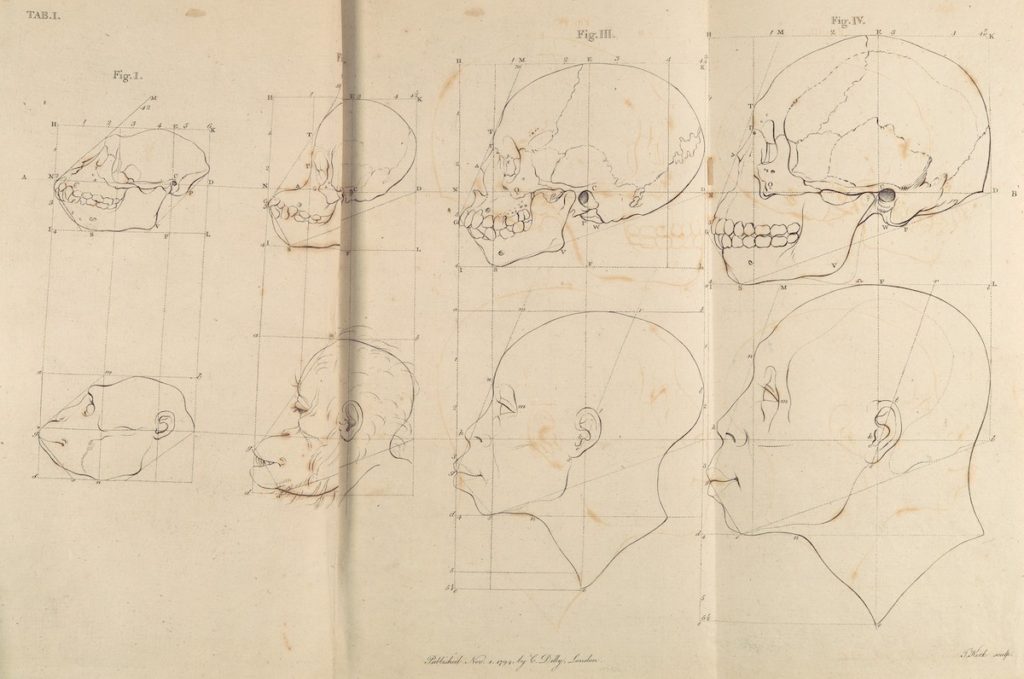

The only exception is the brightly lit Nike of Samothrace (0:58). Beyoncé and her league of dancers ascend the stairs leading up to the winged victory, their black and brown bodies creating undulating waves that contrast against their white surroundings (Fig. 5). Wearing nude leotards that correspond to each dancer’s flesh tone, the women call attention to the false equivalences between nude flesh, monochromy, and marble sculpture. To paraphrase Charmaine Nelson, the material insistence on marble’s whiteness in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries precluded the representation of other skin tones and privileged a white racialized ideal.[14] This idea is voiced in Jay-Z’s final solo verse in which he raps, “I’m a gorilla in the f*ckin’ coupe/Finna pull up in the zoo/I’m like Chief Keef meet Rafiki, who been lyin’ “King” to you?” Referring to the racist trope of comparing black people to apes, Jay-Z’s words resonate with eighteenth-century anthropological studies of racial difference. For example, in the illustrations to Pieter Camper’s The Connexion between the Science of Anatomy and the Arts of Drawing, Painting, and Statuary (1794; Fig. 6), the comparisons between European and African physiognomies to the Apollo Belvedere and an orangutan, respectively, create an implicit racial hierarchy and reinforce the racialized view that marble connotes white skin.[15] By forcing color upon sculpture throughout the Louvre, the Carters thereby challenge the universal assumption that whitened marble is the primary classical referent that has epitomized the history of western civilization in its entirety.

In keeping with the theme of marble throughout the first half of the music video, we are positioned to see David’s Madame Récamier, attired in a gauzy empire-style dress (a robe à la grecque), as the personification of the aesthetic values espoused by classical sculpture. Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s canonical description of sculpture’s “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” comes to mind. With the re-emergence of sculptural theory during the 1750s by writers such as Winckelmann, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, and Johann Gottfried Herder, in conjunction with the outpouring of archeological discoveries at Herculaneum and Pompeii, the robe à la grecque allowed women such as Juliette Récamier to fashion themselves as living statues.[16] Like the aforementioned Emma Hamilton, Récamier was notorious for her own signature pantomime dance with an antique shawl that elided the boundaries between art, classical sculpture, and life.[17] Following her spectacles, Récamier would receive admirers while reclining on a neoclassical chaise longue. The very design of the divan, a hybrid between a bed and a chair, engendered a lounging pose that evoked Roman funerary sculpture and allowed Récamier to continue her performance as a living statue well into the evening.[18] Her body and its intimate proximity to key signifiers of neoclassical material culture made her the paragon of the classical beau idéal stemming from the “marble mania” that had infiltrated eighteenth-century fashion and decorative arts.[19]

The Carters’ staging of Madame Récamier, however, does not solely rely on art hanging on the Louvre’s walls.[20] The long headscarf worn by the dancers makes reference to John Edmonds’s 2017 series Du-Rags.[21] In these photographs of black men wearing their everyday headpieces, Edmonds utilizes the politics of monochromy—replete with the connotations of white marble—to explore the du-rag as a status symbol in the African American community. He likewise gestures towards the du-rag’s origins: the headscarves of enslaved women, used both as protection from the grueling Caribbean sun and to disguise hair considered unruly in the white communities in which they were forced to exist.[22] Returning to the Carters’ tableau vivant, we can now see that the bodies of these two women make present what is absent: the slave labor that was responsible for the consumerist luxuries in David’s Madame Récamier and eighteenth-century French culture writ large.[23]

By the mid-eighteenth century, colonial commerce, including the production and export of coffee, sugar, cotton, indigo, and tropical woods like mahogany, had profoundly transformed European consumption. However, the material realities of these consumer goods were often obscured. As Madeleine Dobie argues, “raw materials were often ‘diverted’ from their colonial points of origin, but only came to embody value when they were transformed into consumer goods that carried other cultural associations.”[24] As such, David’s portrait positions Récamier as the fashionable heiress of antiquity through her consumption of colonial commerce. The Carters’ tableau, however,reveals that the conditions of the chaise longue and the robe à la grecque’s production—which turned on the abuse of the black body—is intimately entangled with the image of Récamier as living statue. The wooden chaise longue, made from tropical woods felled and loaded onto ships by enslaved workers, is quite literally replaced by the women’s bodies. Indeed, the women seem to bear the weight of the chaise lounge, reminiscent of the Egyptian sphinxes, blackamoors, and other racialized bodies carved into the supporting elements of furniture from the period.[25] The headscarf, evoking those worn by enslaved women, now replaces the robe à la grecque sourced from cotton produced by slaves in Caribbean plantations and imported from India. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, much of the cotton worn in the Caribbean (by both enslaved and free people of all classes and races) had been fabricated in India, expanding traditional histories of the triangular trade beyond Europe, Africa, and the Americas to the Indian Ocean.[26] White cotton is positioned here as the nexus between multiple narratives of European colonialism and becomes representative of the many invisible lives behind what is viewed in the twenty-first century as an innocuous and cheap fabric. The two seated women, in contrast to the white cotton, again wear nude leotards that match their individual black and brown skin. White, viewed for so long as sculpture’s default, is no longer neutral.

The duplication of Madame Récamier’s canonical white sculptural form and that of the mahogany chaise longue in and within the static bodies of the two dancers reveals the racial politics imbued in late eighteenth-century consumer culture. More significantly, it makes explicit the performative nature of Récamier’s whiteness. While Récamier fashioned herself as a living sculpture in the image of a classical marble ideal, the dancers do not aspire to that which they imitate. Rather, they return the viewer’s attention back to the omnipresent Beyoncé and Jay-Z. Subverting the logic of the tableau vivant, the Carters—not the paintings—are the new cultural and visual referent. In this vain, it is worth noting that while all the backup dancers wear nude leotards, Beyoncé’s leotard features the signature plaid of the British luxury fashion brand, Burberry (1:37).[27] Just as Récamier fashioned herself as the classical ideal through her consumption of expensive colonial goods, Beyoncé’s Burberry is a declaration of capitalist consumption. Following theories of Blacceleration, which position the Atlantic slave trade as the origin story of modern capitalism, Beyoncé and Jay-Z do not eschew the economic system that has relied on their continual othering.[28] They see their success as intimately tied to it, positioning themselves as both consumer and black body. It is a subtle, if pointed, declaration of Beyoncé’s status as the new, black Juliette Récamier.

In lieu of a conclusion, I wish to meditate on the video’s final cut to Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine (1800; 5:37; Fig. 7), the sitter recently renamed through research by Anne Lafont.[29] The silence and stillness that separates the Madame Récamier tableau vivant from the rest of the Apesh*t video is evoked once more as we are forced to confront Madeleine’s knowing gaze. The Carters strategically crop the portrait above Madeleine’s bare chest, preventing any opportunity for her objectification and obscuring the tropes that characterize the depiction of women of color throughout the western tradition. Like the dancers in the tableau vivant foregrounding Madame Récamier, Madeleine wears a white headscarf. The motif of the headscarf, positioned in opposition to the robe à la grecque, challenges the white beau idéal espoused by Récamier and marble statuary. Embracing this object of resistance, Beyoncé dons her own version, first lounging in the Louvre’s galleries wearing a Baroque inspired headdress, and then later dancing before the Venus de Milo in a floor length black scarf. In the era of Beyoncé and Jay-Z, Benoist’s Madeleine is recast as the new classical ideal, her headscarf a renewed symbol of liberation and success.

Alicia Caticha is a PhD candidate in History of Art

at the University of Virginia specializing in eighteenth-century sculpture and decorative

arts.

[1] This is by no means the first time rap has been performed at the Louvre. In 2014 Toni Morrison invited slam poets from the banlieues of Paris to perform in front of Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa. Alan Riding, “Rap and Film at the Louvre? What’s Up With That?” New York Times, November 21, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/21/books/21morr.html (accessed January 13, 2020).

[2] Beyoncé and Jay-Z standing in front of the Mona Lisa is a now an important scene of “Bey-Z” iconography, first with their 2014 selfie taken in front of the portrait, and more recently with their acceptance speech for the Brit awards, in which they stood similarly before a painting of the Duchess of Sussex (Meghan Markle) dressed in the manner of Queen Victoria. Beyoncé, “Thank you to the Brits for the award for Best International Group. […] In honor of Black History Month, we bow down to one of our Melanated Monas. Congrats on your pregnancy! We wish you so much joy.” Instagram (February 20, 2019), https://www.instagram.com/p/BuHvVDPgVdF.

[3] I am grateful to the editors of Journal18 for their careful readings of this text and, in particular, to Zirwat Chowdury for her insightful comments and vast knowledge of Beyoncé’s oeuvre. Zirwat Chowdhury, “Lemonade’s Enlightenment,” Journal18 (July 2016), https://www.journal18.org/735.

[4] Doreen St. Félix, “The Power and Paradox of Beyoncé and Jay-Z Taking Over the Louvre,” The New Yorker, June 19, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/what-it-means-when-beyonce-and-jay-z-take-over-the-louvre.

[5] Other instances in which Beyoncé has staged art historically symbolic tableau included her pregnancy and birth announcements. See Constance Grady, “How Beyoncé Infused her Social Media Pregnancy Announcement with High Art,” Vox, February 3, 2017, https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/2/3/14484610/beyonce-social-media-pregnancy-art-venus-virgin-mary-mami-wata-awol-erizku; Grady, “Decoding the Artistic References in Beyoncé‘s Gorgeous Birth Announcement for her Twins,” Vox, July 14, 2017, https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/7/14/15971588/beyonce-twins-birth-announcement-madonna-venus.

[6] St. Félix, “The Power and Paradox.”

[7] Angela Rosenthal, “Visceral Culture: Blushing and the Legibility of Whiteness in Eighteenth-Century British Portraiture,” Art History 27:4 (2004), 563–592.

[8] Mary Megan Chapman, “‘Living Pictures’: Women and Tableaux Vivants in Nineteenth-Century American Fiction and Culture” (PhD Diss., Cornell University, 1992); Jennifer Fisher, “Interperformance: The Live Tableaux of Suzanne Lacy, Janine Antoni, and Marina Abramovic,”Art Journal 56:4 (Winter 1997), 28-29.

[9] Chapman, “Living Pictures,” 1.

[10] See David Bindman, Warm Flesh, Cold Marble : Canova, Thorvaldsen, and Their Critics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014). More recently, Anne Lafont has linked this to the development of eighteenth-century conceptions of race. Lafont, “How Skin Color Became a Racial Marker: Art Historical Perspectives on Race,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 51:1 (2017), 89-113.

[11] Despite ample evidence that classical sculpture was indeed painted, the cultural associations of white marble persist to this day. Andreas Blühm, ed., The Colour of Sculpture, 1840-1910, exhib. cat. (Amsterdam: Wanders, 1996); Roberta Panzanelli, Eike Schmidt, and Kenneth Lapatin, eds., The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present, exhib. cat. (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008). On the relationship between Hermes Fastening His Sandal and Neoclassical fashion see Susan Siegfried, “The Visual Culture of Fashion and the Classical Ideal in Post-Revolutionary France,” The Art Bulletin 97:1 (2015), 77-99.

[12] In the original Ovid, Pygmalion’s female statue is unnamed and originally made from ivory. It is only in the eighteenth century that she is transformed into marble and given a name.

[13] Art historian Alexandra Thomas articulates this interpretation of the inclusion of the Great Sphinx of Tannis in Apesh*t and its relationship to Napoleonic imperialism in Cady Lang, “Art History Experts Explain the Meaning of the Art in Beyoncé and Jay Z’s ‘Apesh-t’ Video,” Time, June 19, 2018, http://time.com/5315275/art-references-meaning-beyonce-jay-z-apeshit-louvre-music-video/. Only in one of the last frames of the music video is the Great Sphinx of Tannis lit up so that we can see the actual color of the stone before flashing to Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine (1800), making explicit the connection between Egypt and Africa. This inclusion inserts ancient Egypt into part of a larger narrative of African history.

[14] Charmaine A. Nelson, The Color of Stone: Sculpting the Black Female Subject in Nineteenth-Century America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 57-72.

[15] As David Bindman notes, Pieter Camper was opposed to slavery and the idea that his work could be used to create racial hierarchies. Nevertheless, the imagery provided one of the earliest and most dangerous contributions to the genre of racialized science emerging in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Bindman, Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race in the 18th Century (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002),201-209.

[16] Amelia Rauser has argued that “neoclassical fashion didn’t emerge from the crucible of political revolution, but rather first arose as artistic dress, worn by women to express their status as living statues, as artwork come to life.” Amelia Rauser, “Living Statues and Neoclassical Dress in Late Eighteenth-Century Naples,” Art History 38:3 (2015), 465. Rauser’s more recent work on the colonial materialities of neoclassical dress has further influenced my thoughts on this subject. Rauser, “Neoclassical Dress and Imperial Cotton,” paper given at the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ASECS) Annual Meeting, March 30-April 1, 2017.

[17] Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, Necklines: the Art of Jacques-Louis David After the Terror (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 259.

[18] Lajer-Burcharth, Necklines, 268-274; Heather McPherson, “Madame Récamier’s Serial Portraits: Celebrity as Cultural Currency,” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 47 (2018), 163-184. On the history of the sofa see Joan Dejean, The Age of Comfort (New York: Bloomsbury, 2009), 113-120. See also Madeleine Dobie, “Orientalism, Colonialism, and Furniture in Eighteenth-Century France,” in Dena Goodman and Kathryn Norbert, eds., Furnishing the Eighteenth Century: What Furniture Can Tell Us About the European and American Past (New York: Routledge, 2007), 13-36.

[19] I borrow the term “marble mania” from Ruth Guilding, Marble Mania: Sculpture Galleries in England 1640-1840, exhib. cat. (London: Sir John Soane’s Museum, 2001), 4-15.

[20] The Carters also make reference to contemporary black artists including Deana Lawson and Carrie Mae Weems.

[21] This connection to John Edmonds’ photography was first made by Wesley Morris and Jenna Wortham, “Still Processing: We Louvre the Carters,” New York Times, June 22, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/22/podcasts/still-processing-louvre-carters-beyonce-jay-z.html. On Twitter, others have notably pointed out that Beyonce’s sister, Solange Knowles, wore a similarly fashioned du-rag to the “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” Met Gala. Solange Knowles (@solangeknowles), “I feel heavenly in black – the function #metball,” Twitter, May 7, 2018, https://twitter.com/Oshun_Ba/status/993678527613554688. Steven Nelson has also noted the similarities between the Carter’s staging and Awol Erizku’s portraits that take on the relationship between cutting edge fashion and black identity, particularly Erizku’s 2009 portrait Girl with a Bamboo Earring. See Nelson, “Vision & Justice: Awol Erizku,” Aperture http://aperture.org/blog/vision-justice-awol-erizku/.

[22] In some cases, headscarves were required by law as a mark of enslavement. Lauretta Charlton, “John Edmonds’s Luminous Images of Men in Do-Rags,” The New Yorker, March 18, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/john-edmondss-luminous-images-of-men-in-do-rags.

[23] Heather McPherson notes that from 1797 on, Madame Récamier was known to appear not just in her signature robe à la grecque but with a creole knotted scarf, or vehoule, wrapped around her head. This can be seen in the Joseph Chinard’s portrait bust of Récamier. McPherson, “Madame Récamier’s Serial Portraits,” 165.

[24] Madeleine Dobie, Trading Places: Colonization and Slavery in Eighteenth-Century French Culture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), 17.

[25] On the figure of the blackamoor and eighteenth-century furniture see Adrienne L. Childs, “A Blackamoor’s Progress: The Ornamental Black Body in European Furniture,” in ReSignifications: European Blackamoors, Africana Readings, ed. Ellyn Toscano and Awam Amkpa (Rome: Postcart, 2017), 117-126.

[26] Although the Atlantic supplemented the demand for cotton textiles in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—particularly calico—it did not diminish the Indian textile trade. On the history of the cotton trade between Europe and India, see Beverly Lemire, “Domesticating the Exotic: Floral Culture and the East India Calico Trade with England, c. 1600-1800,” Textile 1:1 (2003), 65-85; Giorgio Riello, Cotton: the Fabric that Made the Modern World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015); and Lemire and Riello, “East and West: Textiles and Fashion in Early Modern Europe,” Journal of Social History 41:4 (2008), 887-916.

[27] I am grateful to Steven Nelson for his identification of the Burberry leotard and for his insightful comments on early versions of this text.

[28] Aria Dean notes that many theorists of accelerationism “aim to recast the racist conclusions drawn over the arc of history about the inhumanity of the black-as-other as something positive to be harnessed.” Dean, “Notes on Blacceleration,” E-flux journal 87 (2017).

[29] Anne Lafont, “Madeleine,” in Le modèle noir: de Géricault à Matisse, exhib. cat. (Paris: Flammarion, 2019), 58. Also see Marianne Lévy, Marie Guillemine Laville-Leroulx et les siens. Une femme peintre de l’Ancien Régime à la Restauration (1768-1826) (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2018).

Cite this note as: Alicia Caticha, “Madame Récamier as Tableau Vivant: Marble and the Classical Ideal in Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s Apesh*t,” Journal18 (January 2020), https://www.journal18.org/4513.

License: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.